Wild Life

seal, like a mirage

you shimmer to sudden life

and likewise vanish

I’ve always been a capable spy. Drawn to inner landscapes, I drift easily into a private theatre of thoughts and images, lingering there while I gaze in parallel at the real world. But despite my watchfulness, important wildlife affairs still go unseen. And those very proceedings have the potential to affect my life. I learned this when I was nineteen and a bull orca rose out of the water directly in front of my kayak. I wasn’t expecting whales and it was the first orca I’d ever seen. The four-foot dorsal fin made a noise like the flexing of sheet metal as it cut through the air toward me. My paddles whirled in full reverse, fuelled by a thumping heart and a surge of adrenaline, which didn’t abate until the whale came abreast of me, his small all-seeing eye examining me before passing by.

In that moment I realized that the scope of my watchfulness needed to expand: I needed to become more observant, both of my immediate surroundings and of the larger view. I also needed to improve my ability to predict the general patterns of weather and wildlife—patterns that had the potential to affect the routines of life on the coast. With all the assurance of youth, I presumed these skills were not only something that would protect me, but also something I could master. It never occurred to me that animals could be just as fallible as humans. And that, despite my best intentions, my skills of observation could fail me.

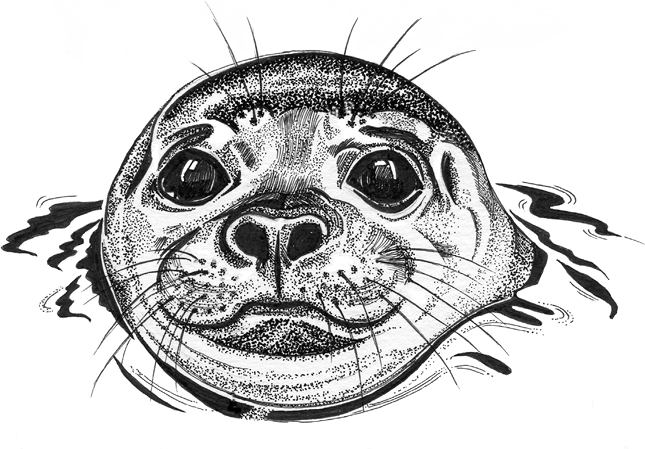

My lessons in marine mammal behaviour began when I became a seal-pup nanny for the family who lived in Maltby Slough before me. The seal in question was a prematurely born harbour seal pup, found in a state of hypothermia and near drowning. He was raised by Mike and Cathie and their daughter, April, on the decks of their floathouse. And he was named Tutsup, the Tla-o-qui-aht word for urchin, a perfect double entendre for this orphan, who—when curious—could extend his whiskers until his nose bristled like a spiny sea urchin. Tutsup could also be shortened to Tootsie, or Toots, to match his babyish cries of maaaa! and the way he slurped his soother—an old wetsuit bootie—as if it were a thumb.

On the advice of marine biologists, Tutsup was tube-fed a life-saving fishy concoction and kept strictly away from the water. His white lanugo—a premature birth coat—nearly cost him his life, unprepared as he was for cold-water immersion. Had he been born further north, this coat would have kept him warm as he rested on an ice floe, but in the less frigid climes of the forty-ninth parallel, this coat is shed in utero, allowing full-term seal pups to be born swim-ready. For Tutsup, swimming wasn’t an option until his swimming coat grew in, so he had to be kept dry. But keeping a baby seal dry and fed is a full-time job. And two days a week, when Tutsup’s adoptive family were all at work, I drove up to Maltby Slough, donning my nanny cap as their floathouse came into view.

Single-handedly tube-feeding an obstinate infant seal is a handful of a job, prone to failure and mess. Nor did things improve when Tutsup grew old enough to digest the chunks of herring we were instructed to force-feed him. Should my forefinger not push the pieces far enough down his gullet, the whole disaster would be projected—cork-like—straight back at me. Through it all, I marvelled at the exquisite pinkness of his inner mouth, the muscular curl of his tongue, the tight round rolls of neck fat and the pathos of his hooting cries. Like a crawling child, he followed my movements, intent on sucking the soft cotton of my pant legs. If allowed, he would wad the fabric into a slimy wet mass—anchoring me in place by the sheer force of his pull. As he grew older he began to lean over the dock and put his head in the water, blowing bubbles—and raspberries—for our mutual entertainment. And one day, when the time was right, he slipped into the water, lured by the magnetic pull of instinct.

Seamlessly, the water claimed him, erasing his domestic past and reshaping him as a wildling. Tutsup began to absent himself for longer and longer periods. He learned to catch his own fish, and stopped hooting and suckling, or seeking human companionship. Occasionally he hauled out to rest under the dock, where his loud breathing gave away his presence. Like a parent whose child has left home, part of me longed for Tutsup to keep our connection. But however bittersweet, I knew that what had happened was the best possible outcome. From time to time I saw him, either from my motorboat or from my kayak, and when I did, I couldn’t help calling out to him, secretly wishing he missed me, hoping for a glimmer of recognition. Most times, though, his response was ambiguous—dark head sinking without any gesture beyond eye contact. I began to see the limitations of my role as a watcher, confined as I was to the world above water.

That feeling of limitation continued during the years I worked as a whale-watching guide. Daily, I studied the visual language of whale spouts—those spectral puffs of distilled breath, nuanced by wind, sky, the size of the whale, its distance, speed and many other factors. Trip after trip I tried to gauge how long a whale would remain submerged, how soon it would reappear, how it might behave once on the surface. My predictions became more reliable, despite the beautiful prerogative of whales, like seals, to conceal themselves by slipping away into the depths, leaving me longing to know what they did when lost from view.

But while it was rich in marine mammals, life on the water didn’t preclude the observation of land animals. In fact, terrestrial animal behaviour gained a new dimension in my work as a kayak guide. Kayaking is a perfect environment for spying on animals. The boats travel close to shore, often observing the intertidal equivalent of cross-border traffic. This interface of land and sea is the domain of herons, ducks and shorebirds. It’s also attractive to mink and raccoon. They can be seen foraging for small crabs, or sniffing the air before setting off on a swim, always with a destination in mind. Black bears, too, are drawn to the intertidal zone, endlessly turning over rocks in search of crabs. In some areas the clunking of boulders makes up a common, multi-dimensional aspect of the low-tide landscape.

Over the years these observations began to coalesce, melding into a strange combination of knowledge and instinct. But as with all areas of study, the more I learned, the more I wanted to know.

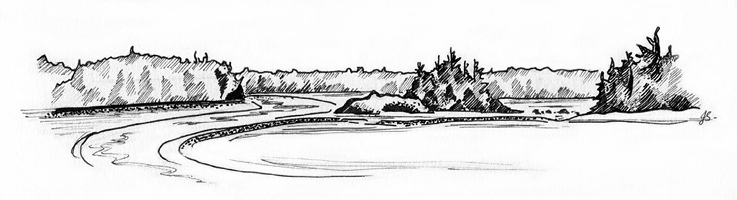

It was not just because of Tutsup that I took up swimming expeditions the summer after I moved to Maltby Slough. So many creatures used the channel as a transportation route that I thought it would be fun to do what they did, follow similar paths, map out my surroundings from their perspective. At low tide, the channel lent itself to exploration. I could zigzag upstream by swimming from the house to the mudflats on the far side, walking for about ten minutes, swimming across again and walking further. In this way I could reach the corner where the channel narrowed and curved out of sight—a high-traffic area for wildlife in the slough. Wolves often crossed here, noses and tails held high as they swam with remarkable speed. My own swimming was also speedy, on account of the frigid temperature and strong current. The constant feed of fresh water meant that the slough was always cold, even when water temperatures elsewhere warmed. The current was another matter, often dangerously strong depending on the tide. I chose my moments with care, not wanting to find myself stranded downstream, cold and wet and tired.

One glorious August afternoon, I headed out to swim and walk. Leaving home was the most challenging part of the adventure. The floathouse was tucked in the curve of a small bay and the ebbing current aimed straight at it, undercutting the shore of the island behind it before rebounding. The resultant swirl of water spread across the channel, bumping back into the main thrust of the ebb. It was the widest span I could choose to cross, and the most complicated. Added to this was my body’s dubious ability to adjust to the icy baptism. Always a challenge, I would sit on the edge of the boat with my feet immersed, waiting for a small seed of courage to grow and blossom.

On this windless day, the tide was low, and small, airborne flocks of shorebirds banked and flashed their way along the water’s edge, seeking sustenance for their journey south. The mudflats were bright with the carpet of moss-green algae that spreads and thickens throughout the summer—algae that is a nuisance when boating, but the fibrous cushioning of which felt good underfoot, protecting me from stray rocks and excess mud. For a change, I decided to walk downstream toward Browning Passage. I wanted to see how far I could make it without encountering any impassable, ankle-grabbing sections of mudflat. These were usually the low-lying places, where trickling water pooled and there was little eelgrass. I didn’t get very far before wading back out and swimming downstream to avoid a quagmire. I couldn’t cross back over to Aquila Island because the shoreline was steep and rocky there—clad with a horde of barnacles. I swam for as long as I could stand the cold, then waded ashore and continued along my way.

As excursions go, it was a messy one. I began to resemble a swamp monster, strung with ribbons of eelgrass and smeared with mud. I gave up on my plan and decided instead to visit the cabin my neighbour was occupying in his capacity as a squatter. There was a garden there and I’d been offered a small plot of earth where I planted kale and potatoes. Without a water supply, gardening was more whimsical than practical, but I liked the idea of it. My neighbour was practising a very different kind of gardening—one we didn’t discuss. But at this late date in the summer, he was nearing his harvest time, which may have explained his absence that day.

I climbed up the dark rocks—avoiding barnacles—and sat for a while, soaking up the warmth and the scent of woodbine honeysuckle. From this viewpoint I was able to see the stickiest areas of mudflat and think about the route home. Later, I wandered into the garden and examined withered stalks of potatoes and small, tough leaves of kale, hoping that no respectable gardener would ever see my handiwork. It wasn’t until I was leaving that I noticed something different—large claw marks, slashed brightly across the pale bark of an alder tree, the orange flesh of the tree exposed and bleeding. The marks were new and they were clearly the work of a bear. My neighbour hadn’t mentioned a bear to me, a fact that made me wonder just how new the marks were. Hmm, I thought, time to head home.

I pulled apart the wall of honeysuckle vines and peered out over the mudflats, searching for boulder-sized black shapes. Bears usually forage at shoreline, looking for crabs, or using their teeth to scrape barnacles from logs for a popcorn-like snack—extra crunchy. I took care in my search, squinting into the distance, shielding my eyes with both hands. Happily, there was no bear visible and I stepped lightly onto the mudflats. When, halfway there, a horsefly found me—buzzing and landing despite my slaps—I began to lose concentration and fortitude, in equal measure. Bears were generally avoidable, horseflies weren’t. I strayed from my intended path and my feet became bogged down in the stickiest of the mud. I made such a perfect target that a second horsefly joined the fray, scenting a blood meal. My slaps doubled in number as I twisted and writhed, trying to escape the flies’ cutting mouth parts. I longed for the swim home, to rid myself of mud and insects and grubby strands of eelgrass. Such distractions undermine even the best of safeguards.

Once I could see the boat I decided to swim for it, even though I was still upstream of my usual crossing point. I was warm from my efforts and the water itself would be warmer than before. The tide had turned, imbued with the heat of sunbaked mudflats as it flooded the bay. I splashed in, wallowing and sighing with relief, pulling low the brim of my hat to thwart the location-finding of malicious horseflies. I estimated my course to the floathouse, taking into account the sweeping arm of the tide. Then I swam quickly, hoping I wouldn’t get too cold.

My boat’s small white shape grew larger as I swam. It was an important target, one which I had no intention of overshooting. But I needed a bigger picture of my place within the channel, to see where the current was sweeping me. I treaded water, turning a circle and looking around. The dark head of a seal caught my interest as I turned, my vision blurring as salt water splashed into my eyes. The seal was a few body lengths from my shoulder, heading the other way. Tutsup had often seemed spooked by the presence of swimming humans when he was little, but he had a dark head. Could it be him? Had he finally come to see me? Several years had passed since I’d last poked a herring down his throat. I couldn’t be sure if that broad neck belonged to him. And the fur seemed extra dark. There was also something wrong with the shape of his head. It was long and flat and not very seal-like. Kicking hard to keep my place in the current, I tried to clear my eyes of salt water and get a better view. That was when I noticed the creature’s ears. Harbour seals don’t have visible ears.

The realization that I was swimming alongside a black bear had a similar effect on me as my early encounter with the bull orca. I shot across the channel without concern for the current or the temperature. Was the bear aware of me? I didn’t know. Several times I shoulder checked, but thankfully the two black ears kept moving progressively toward the opposite shore. Later, I was surprised that so little of the bear’s body showed above water, but at the time I thought nothing of it. With a surge of great energy, I hauled my flailing body over the gunwales of the boat and looked behind me again. By now, the bear had also finished swimming and was wading out of the water, eelgrass streaming from his haunches. I particularly enjoyed his choice of landing site, smirking at his arrival in the middle of the very quagmire I’d just escaped, where he sank into the mud even as he shook out his coat—water spraying brightly from his fur. From my position of safety, I began to laugh, the sound of my relief pealing out into the echoing open space. Two creatures swimming on a hot late-summer day, neither one of us plotting a careful course, our actions unguided by any sense of vigilance, or wisdom.

I peeled long strands of eelgrass from my legs and watched the bear’s muddy progress. Despite the distance I felt sure I could see two horseflies circling his head.