Losing Power

the outer isles sing

their wave-battered songs, tell tales

of storm wrack and woe

It’s a late-September morning in 1993. I’m drinking a mug of tea, one hand raised against golden, low-slanted sunlight. Airborne mew gulls are feasting on insects, wheeling and crying. Over and over they loop the sky, calling out summer’s end in sweet-sad notes—meeeewww! From my cabin at Stone Island, I am looking south across the harbour at small, forested islands and glass-like water. I can see Tofino’s waterfront, where barely a boat is moving. Nothing in my view hints at the possibility that a mile farther out to sea the morning is not equally peaceful. Or that a surfer at the beach might be enthusing over the unusually large swell, formed by a storm far, far away across the Pacific.

Other than the gulls, little else stirs. If I speak, or move, I could shatter the moment. I’m awake and conscious, but untethered in the hypnotic way that only seems possible at the beginning of a day. Steam rises up from my mug and I hover over it, inhaling, while an invisible tide of thoughts slips in and out of my mind. The quiet is even sweeter than sleep. Later in the morning I will remember this feeling and long to recapture it. But when two squirrels break into a noisy argument and skitter branch to branch in the hemlock tree beside me, I pour the dregs of my tea onto the roots of a yellowing tomato plant and go inside. My day off from work is not a day of freedom.

Marine charts of Clayoquot Sound are like an artist’s study in colour values; blues, greens, tan and white. Nowhere is the land uniform. Fjord-like inlets knife their way deeply into mountains, while rocks and islands pockmark every expanse of blue. Some mountains rise and fall with sensual curves, while others are steep and angular, their contour lines packed tight like cards. Shorelines are shown as inky squiggles in steep rocky areas, or green-dotted swaths of mudflat, or wide curves of sand. Some islands are large enough to carry their own mountains, while other islands are only a couple of acres. Still others are mere rocks, proud bearers of a single tree.

This summer, my partner Carl has been building a small cabin on the tiny outer-coast island of Echachis. The island was once a traditional summer whaling village and is a significant part of his Tla-o-qui-aht heritage. Lacking a single contour line, Echachis is represented on the chart as a tan-coloured splot. It is surrounded by blue that quickly becomes the white of the open Pacific. No other land stands between Echachis and Japan. No barriers protect it from storms. This island is the vanguard, its rocky shoreline inked with clusters of reefs and navigational hazards. The roughed-in cabin is about to be boarded up for winter, as the combination of building materials, small boats and heaving seas can be disastrous. The extreme outer coast of the Pacific Northwest presents an elevated quotient of danger. Islands like Echachis may seem like paradise in summertime, but winter storms transform everything.

Although Echachis is visible from Tofino, the cabin is on the far side of the island, facing the sunset. One way to get there is the circuitous, ocean-exposed way, which culminates in a narrow surge channel, barely visible on the chart—the marine equivalent of a one-car alley between buildings—replete with lurking rocks and surf. There is also a direct, sheltered route, which passes between Echachis and Wickaninnish islands over the sandbar that connects them at low tide. Either route involves strict observance of the tides. A retreating tide can beach a boat in seconds, leaving the occupants marooned for up to twelve hours, possibly longer. Always, it is preferable to make the trip with two people: one to hold a shoreline; the other to throw anchors, raise the motor and pass goods overboard.

This golden day offers a chance to retrieve a generator, which I need at Stone Island. The tide should be high enough for me to take the easy route, which is the most important thing. I should have a second person to help me carry the generator, but I brush that problem aside. Asking for help is a personal battlefield. There is the creeping sense of defeat that goes with every request, the feeling that—as a woman—I am not capable. The youngest of five siblings, I was always the last to be chosen for tasks or opportunities. Nowadays, I make up for lost time by choosing myself wherever possible. So today, while I do need help with the generator, I can’t face asking for any. I have a hazy plan (90 percent willpower and 10 percent physics) to form loose lumber into railway-style tracks. By some miracle the tracks will also convey the generator from the rocks to the boat… I mentally gloss over that particular detail and chuck a coil of rope into my little open boat. I check the gas tank: half full—more than enough.

On days when the sea is glass calm, driving a boat is akin to flying. I feel as if I’m a bird—a shearwater perhaps—inches from the surface, adjusting my angle of glide, and soaring. Sea and sky blend into a single bright future. There is pleasure in carving a turn and feeling the responsiveness of a boat’s hull. There is elation at the rush of air, the speed.

On this morning the boat ride seems to make everything possible. The fallibilities of my plan are eclipsed by the pleasure of the moment and the impossible breadth of the horizon. As I head for Duffin Passage, my eyes are fixed on the faraway blip of land that is Echachis and it’s only by chance that I glance over at First Street Dock and see the blur of two arms waving. I recognize Rob, a carpenter who has been helping with the cabin. He’s trying to flag me down. It turns out that Rob has just paddled in from Echachis, where he stayed overnight. He wants to return, bringing his tools with him. But his tools won’t fit in his nineteen-foot expedition-style sea kayak. He asks for a ride, but he says the tide won’t be high enough for us to go the easy way. I look again at the calm harbour and shove the first crate of Rob’s tools into the bow of my boat. More crates follow. As my thirteen-foot Boston Whaler transforms into a pint-sized freight barge, I wonder how I’m going to fit Rob and his kayak, too. We strap the kayak on top of the crates, its bow jutting for’ard like a tall-ship’s prow. We leave a perfect space for Rob to crouch on the bench right next to me.

My boat has been built with a number of safety features in mind: enough floatation to survive being swamped by waves; a trimaran hull and a low centre of gravity for stability; and low sides, to avoid buffeting by wind. Even though she is so small and close to the water, the boat has proved herself on the ocean time after time. As loaded as she is at this moment, I have faith in her ability to take Rob, his kayak, his tools and me to Echachis. But as we pull away from First Street Dock, I note the slowing effect of all the weight on the boat. It takes us a while to get up onto a plane, even though I nudge the throttle to maximum. The engine roars and eclipses any chance of conversation.

We leave the flat waters of the harbour and head toward a narrow, rocky passage leading to the open ocean. Here, a large swell rolls toward us, crests and breaks. This is so unexpected that I stop the boat while I am still on the safe side of the passage, mentally abandoning the trip. But Rob is blasé. “It’s not that bad,” he says. “I paddled it this morning.” I consider his opinion. Swell can be manageable when the sea surface is smooth and there is a reasonable distance between each wave. Rob is also a sea kayak guide, so his judgment should be reliable.

I wait for the series of waves to pass. Then I gun the motor, ploughing against the added weight and pushing through the passageway. Halfway out to the northwestern tip of Wickaninnish Island, doubt returns and I slow the boat again. But once again Rob reassures me that the outer coast is really not that bad—he says he knows I can do it. I’ve been driving boats for years, yet his belief in me still feels good. When I first moved to the coast, boating was a primarily male-dominated field. I had to prove my credentials. I consider those credentials now as I go forward at half-throttle. Boat handling skill is the outward marker of ability. Experience and judgment are the invisibles.

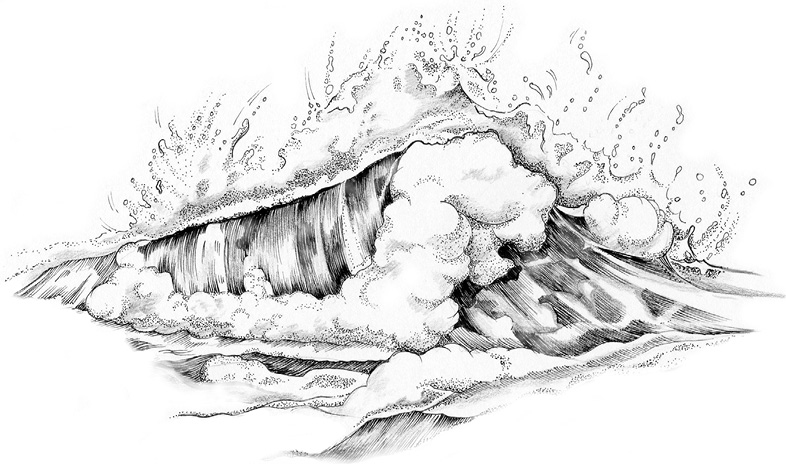

When we reach Wickaninnish Island, the outer-coast section of the route comes into view and I see what lies ahead. Everything is moving—heaving and tossing. And everything is white. Silvery sea-foam is being blasted into the air where it catches the morning light. The location of the reefs, usually hidden, is now fully revealed as the swells surge over them and erupt into frothing tiers of brightness. We are only one nautical mile from our destination, but the path will be a minefield of watery explosions. Forget credentials. Without even slowing, I turn the boat around.

“What are you doing?” yells Rob. “You can’t go back, we’re nearly there!”

I gesture at all his gear and at the ocean. “I’m not doing it; it’s not safe,” I shout above the roar of surf.

“What do you mean?” he yells back, “You can’t turn around now. We’ll make it, no problem.” Unerringly, he finds my weak point. Perhaps I have somehow led him to it: “And I always thought you were a real west coaster,” he says.

I come from a family of risk-takers. Name an improbable situation and my father likely escaped from it. My mother, too, galloped through life apparently without fear. Together as a family, we endured many long hours on rough Caribbean seas—the endless slam of hull to wave, the crusted rime of salt on skin—but our family stories were never as extreme as Dad’s early adventures: fulfilling a bet by doing a handstand at the top of a two-hundred-foot oil derrick (and losing his job for it); numerous encounters with sharks; severing a fingertip in an Amazon piranha encounter (the fingertip stuck back on by my mother); first ascents of Huagaruncho, Nuptse, Roraima, Torres del Paine; the driving of twelve-foot boats from the island of Trinidad to its sister isle, Tobago, through the Bocas del Dragon (the Dragon’s Mouth), a legendary strait separating the Gulf of Paria from the Caribbean Sea—its sea state so formidable he required a tether line to haul himself back aboard whenever he was tossed out.

Years later, my teenaged brother and sister drove a boat over this same twenty-or-so-mile route when Dad asked them to deliver a much-needed water tank. I was still a child, but I understood that this was a rite of passage of sorts. I whined about not being able to go, but my plea went unheard. Being “too young” was a constant parental refrain, one I railed against, creating fantasy adventures of my own, instead. That day the conditions were challenging and my father monitored my siblings’ journey with gleeful interest. The story quickly became an inextricable part of the family repertoire.

Past narratives obviously influence future ones. In some ways I’d been raised to risk tackling the sea conditions I was looking at. But recent years of kayak guiding had reshaped my mind with an emphasis on caution and safety. And my studies had taught me about inquests: the way an accident is unravelled and decoded; the way my decisions—my credentials—would be later examined in the case of an unfortunate event. I sat in the boat, looking at the sea, my early life doing battle with my later life.

It’s terrible to be wrong. It is infinitely worse to sense that you are going to be wrong and to choose it anyway. We really are so close. I let myself be persuaded by Rob’s argument and steer into the raging white water, the weight of my choice dragging behind me like a sea anchor. A host of invisibles rises up in my mind, doubt after doubt, each one lost to the roar of the ocean.

The rate of progress is painful. The motor groans as it pushes us up each wave and I try to avoid surfing as we fly down the other side. The route becomes serpentine as I weave between the reefs, timing my passage with the movement of swell. Some waves are manageable; others are intimidating and my eyes seek danger in every direction. Kayakers call these reefs boomers, for the sudden noise of their explosions. But crashing waves are only the second part of a boomer’s equation. In the first part, the wave feeds its size by sucking the water backwards, revealing hidden rock beneath. Unsuspecting boaters can be stranded high and dry on such rocks, unable to move out of the path of the fully grown wave. This is where experience comes in. Knowledge of an area is vital. I do know this area, but as we head further out, the size and ferocity of the waves increase and the boat is pushed from all directions.

I see a swell mounting ahead. It builds and builds. When it doesn’t crest, I realize that it is going to keep growing until it is monstrous. But while I’m eyeing this giant, a different wave thunders sideways at us, taking me by surprise. I accelerate through its wash just when the giant finally erupts, roaring, hurling foam and obliterating our path. For a moment the world goes white. It’s hard to tell which way is up. As the spray dissipates, I see Rob’s face. Suddenly, there’s fear. He didn’t think it would be like this. I wonder if he can read my own face. He won’t see pride there. By saying yes, I relinquished the most important invisible, my judgment. But now, turning back is just as bad as going forward. Whether I am foolish, or afraid, or weak, or stupid, I am committed. A seabird shoots by and skims the waves. I picture myself doing the same and feel a surge of optimism. Skill and experience—I still have those.

I grit my teeth and grip the tiller. “If a wave tries to break on us, lean forward and hold on!” I yell. “I’ll have to go full throttle, or it’ll flip us over.” Rob nods and crawls, lizard-like, up to the bow to watch for hotspots. We inch forward. The trip is taking forever—at least three times longer than planned, because of the conditions and the added weight. Even though it is barely recognizable to me, I’ve paddled this section of coastline many times. I keep my bearings and begin counting down to the most challenging part of the trip, which will be when I nose the boat through several reefs and into a long surge channel little more than a boat’s-width wide.

Eventually we get close. Two more mountains of white water to negotiate before the surge channel. There’s a chance we’ll make it. My fingers are clamped to the tiller, adrenaline flooding through me.

And that’s when the motor loses power.

It’s hard to describe what happens when you’re confronted with the worst possible scenario. I am scared, but necessity keeps me functioning. I am amazed it is possible to think at all. The boat wallows in the trough of two huge swells amid walls of water so high that I can’t see land. I imagine a wave breaking on us, or worse, flipping the boat.

Suddenly, the motor starts up and we move forward again. My heart soars! But the moment is short-lived, and after a few seconds the roar fades to a whisper. A pattern begins to emerge. The motor putters. And then it fades. It putters and then it fades. My heartbeats mimic the rhythm, stopping for seconds at a stretch in nauseating moments of apnea. Each time, barely breathing, I wait for the motor to re-engage. Mentally, I conjure my list of reasons for a breakdown. I stop at the first one—gas. Of course. The gas tank is almost empty: tip it one way and the motor gets gas; tip it the other way and the motor sucks air. The swell is causing us to ascend and descend, tilting the boat and the gas tank. We’re surrounded by reefs and we’re running on fumes. In my early-morning planning, I hadn’t factored in the extra weight and the unexpectedly long route, made even longer by the conditions. This is the era before cellphones and we don’t even have a radio. I close my eyes, then open them and look at Rob, lying clamped to the bow. I look at the kayak, imagining different ways of towing a motorboat with it, all of them useless. I stop breathing, as if that will give the motor energy. Miraculously, it seems to. The boat keeps going, barely, but just enough for us to keep sliding forward—a bizarre, marine caravan of woe.

Despite poor odds, we near the final approach. I steer the hiccupping boat through the surge channel, unforgiving rock walls within touching distance either side, a huge wave thrusting up behind. The velocity of the wave shoots us through the passage into a calm half-moon bay fringed with sand. And as we skim onto the protected water, the very last vapours of gas evaporate. The motor dies.

After we unload and anchor the boat, Rob and I compare the shaking of our limbs. I can barely speak, surges of emotion washing through me: relief at our salvation, anger at Rob, exhaustion—mental and physical. But I can’t let myself feel tired. I have a new problem to deal with. I’m at Echachis, with no radio and no gas. Rob helps me carry his kayak over to the calm side of the island, where I launch it and begin the hour-long paddle to Tofino. I don’t know when I’ll be able to drive my boat home, but I can’t leave it at Echachis. I live on an island. I need it.

As I paddle, remnants of adrenaline shudder through my limbs. Ironically, I’m taking the route I originally intended to take. I marvel at the calmness of the ocean on this side of the island, but otherwise I just hack at the water as if going faster will make things better. Unable to think about what happened, I expend savage energy, flinging anger from me like so much spray. By the time I reach Tofino my legs can barely carry me and I flop on the beach like a stranded jellyfish, gazing at the placid sky, wondering what combination of elements kept the boat going until Rob and I reached safety.

Much later, after the sun has set on an otherwise perfect west coast day, I am able to reflect on the arc of my nearly disastrous journey. I examine the many small changes that caused the plan to shear away—degree by degree—from its intended course. When I think about the way I let myself be persuaded, questions rain down on me: Why did I say yes? Would a real west coaster tell Rob to screw off and get his own boat? Would Rob have even challenged a man that way, or do women jump a higher bar just to achieve equality? Was this about gender, or plain old strength of character?

Age-old questions. In the end, I settle on a mix. I did feel bullied into saying yes. But I was also raised by risk-takers. And because of my place in the family pecking order, the adventures usually belonged to others, not me. Like a crab clinging to my storyline, I still wanted to be chosen for the job. How deep they run, these yearnings formed in childhood. How long it takes to see them, do battle with them and learn how they apply to the mechanics of life.