• Using times tables backward

• Remembering long division

• Understanding chunking

Just as subtraction is the opposite of addition, so division is the opposite multiplication. More precisely, 24 ÷ 6 is the number of times that 6 fits into 24. We could rephrase the question as “6 ×  = 24”; by which number do we need to multiply 6 to get 24? What is this useful for? Well, suppose I want to share a packet of 24 sweets among 6 salivating children. If each child is to get the same number of sweets (seems a good idea—to avoid an almighty argument) then that number must be 24 ÷ 6.

= 24”; by which number do we need to multiply 6 to get 24? What is this useful for? Well, suppose I want to share a packet of 24 sweets among 6 salivating children. If each child is to get the same number of sweets (seems a good idea—to avoid an almighty argument) then that number must be 24 ÷ 6.

The usual symbol for division is “÷,” but computers often display it as “/.” Another way of representing division is as a fraction, so “24 ÷ 6,” “24/6” and  all have exactly the same meaning.

all have exactly the same meaning.

BEGIN WITH SOME PRACTICE. TRY QUIZ 1.

As usual, the starting point for division is to get used to working with the small numbers, 1 to 9. In particular it is very useful to be able to work backward from the times tables, and to be able to answer questions like this: 6 ×  = 42. (This is the same as calculating 42 ÷ 6.)

= 42. (This is the same as calculating 42 ÷ 6.)

When we are doing division with whole numbers, something rather awkward can happen, something that we didn’t see with addition, subtraction or multiplication. In the case of addition, for example, if you start off with two whole numbers, then when you add them together, you will produce another whole number. But with division, this can go wrong. If we try to work out 7 ÷ 3, for example, we seem to get stuck. If we know our three times table, then we know that 7 isn’t in it: the table jumps from 2 × 3 = 6 to 3 × 3 = 9. So what can we do?

Let’s go back to the example of dividing up sweets between children. Suppose we have 7 sweets to divide between 3 children. To avoid a fight, we want each child to get the same number of sweets. How many can they each have? With a little reflection, the answer is 2. That leaves 1 left over, which we can put back in the bag (or eat ourselves). We can say that 7 divided by 3 is “2 with remainder 1.” We write that as:

for short. Questions like this are a tougher test of your times tables! This is how to tackle them.

• If we want to calculate 29 ÷ 6, the first thing to do is to go through the six times table to find the last number in that list which is smaller than (or equal to) 29. With a little reflection, we see that number is 24.

• The next question is: 6 ×  = 24? The answer is 4. So 29 ÷ 6 is equal to 4, with some remainder.

= 24? The answer is 4. So 29 ÷ 6 is equal to 4, with some remainder.

• The final step is to find out what that remainder is: it is the difference between 29 and 24, which is 5. So the final answer is:

29 ÷ 6 = 4 r 5

Sometimes it is best to leave the answer to a division question as a remainder. But there are other options. To go back to the example above, where 7 sweets were divided between 3 children, we had an answer of 7 ÷ 3 = 2 r 1. One way to deal with the 1 remaining sweet is to chop it into thirds, and give each child one third. In total then, each child will have received  sweets, so

sweets, so  .

.

It is not hard to move between the language of remainders and fractions:

• Once we have arrived at 2 r 1, the main part of the answer (that’s 2) remains the same.

• Then the remainder (1) gets put on top of a fraction, with the number we divided by (3) on the bottom, to give  .

.

So, to take another example, having worked out 29 ÷ 6 = 4 r 5, we can express this as a fraction as  . It is dealing with remainders which gives division its unique flavor.

. It is dealing with remainders which gives division its unique flavor.

REMAINDERS AND FRACTIONS. TRY QUIZ 2.

The word “chunking” is a fairly new addition to the mathematical lexicon, the sort of thing that might make traditional mathematics teachers raise their eyebrows. All the same, many schools around the world teach this method today. So what is chunking all about?

Actually, far from being something fancy and modern, chunking is an ancient and very direct approach to division problems involving larger numbers. It is just the word that is new!

Suppose we want to divide 253 by 11. The idea is to try to fit bunches of 11 inside 253, thereby breaking it up into manageable chunks. So the smaller number (11) comes in bunches, and the larger number (253) gets broken down into chunks. Got that?

Now, a bunch of ten 11s amounts to 110, and this certainly fits inside 253. In fact, it can fit inside twice, since twice 110 is 220 (but three bunches comes to 330 which is too big).

So we have broken up 253 into two chunks of 110, which with have been dealt with. The leftover is 253 − 220 which is 33. To continue, we want to fit more 11s into this final chunk. Well, 11 can fit into 33 three times. All in all then, we fitted 11 into 253 twenty times and then a further three times. So 253 ÷ 11 = 23.

With chunking the key is to start by fitting in the largest bunch of 11s (or whatever the smaller number is) that you can, whether that is bunches of ten or a hundred. Doing this reduces the size of the leftover chunk, making the remaining calculation easier.

TRY THIS YOURSELF IN QUIZ 3.

You may find it helpful to make notes as you work, to keep track of the chunks that have been dealt with, and the size of the leftover chunk.

What happens when the numbers involved are larger? Suppose we are faced with a calculation like 693 ÷ 3. Chunking is one option, but when the numbers are larger, it’s worth knowing a careful written method.

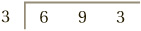

Division is set out in a different way from the column approach of addition, subtraction and multiplication:

One reason for this change is that when doing addition and multiplication we work from the right (from units to tens to hundreds). In division, we work from the left, starting with the hundreds. The reason for this swap will become apparent soon!

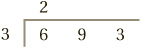

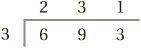

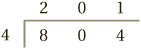

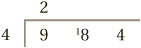

For now, the way to approach calculations such as the above is to start with the hundreds column of the number inside the “box” (in this case, 693, known in the jargon as the “dividend”), and ask how many times 3 (the “divisor”) fits into it. That is to say, we begin by calculating 6 ÷ 3. The answer of course is 2, so this is written above the 6, like this:

With this done, we move to the next step, which is to do the same thing for the tens column, and then the units. After all this, the final answer will be found written on the top of the “box”:

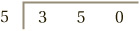

One thing to remember is that 0 divided by any other number is still 0. So if we are working out 804 ÷ 4, when we reach the tens column, we have to calculate 0 ÷ 4. This is 0. So working it through exactly as we did above, we get:

IF THAT ALL SEEMS OK, THEN HAVE A GO AT QUIZ 4!

As you might have feared, things do not always go quite as smoothly as the last section suggests. What might go wrong?

Suppose a group of 5 friends group together to buy an old car for £350. How much does each of them have to pay? The calculation we need to do is 350 ÷ 5. We can set it up as before:

According to the previous section, the first step is to tackle the hundreds column: 3 ÷ 5. But 5 doesn’t go into 3. The five times table begins: 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, … with 3 nowhere to be seen. So we’re stuck. What happens next?

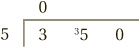

The answer is we use our old friend “carrying,” albeit in a different guise from before. Also, remember remainders: 5 fits into 3 zero times with remainder 3. So we write a zero above the 3. But this leaves a leftover 3 in the hundreds column. This is carried to the tens column where it becomes 30. Added to the 5 that is already there, we get 35 in the tens column. That’s usually written like this:

Now we can carry on as before: since 35 ÷ 5 = 7:

So we arrive at an answer of 70.

What happened during this new step was that we essentially split up 350 in a new way. Instead of the traditional 3 hundreds, 5 tens and 0 units, we rewrote it as 0 hundreds, 35 tens, and 0 units. With this done, the calculation could proceed exactly as before.

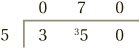

Let’s take another example. Say 984 ÷ 4. As ever, the first thing to tackle is the hundreds column, where we face 9 ÷ 4. This is slightly different from the last example, where we had 3 ÷ 5. In that case, 5 could not fit into 3 at all; it was just too big. But this time 4 does fit into 9. The answer is 2, with a remainder of 1. This remainder gets carried to the next column. The 2 is written above the 9. That takes us this far:

The next stage is to tackle the tens column, where we have 18 ÷ 4. Once again, this doesn’t fit exactly, but gives an answer of 4 with remainder 2. So the 4 gets written above the 8, and the remainder is carried to the next column:

The final step is the units column, where we have 24 ÷ 4. That is 6. So we have our final answer: 246.

TIME TO PRACTICE THESE, IN QUIZ 5.

There are few expressions in the English language that induce as much horror as “long division.” In fact, it’s not so bad. Long division is essentially the same thing as the short division we have just met. It’s just a little bit longer.

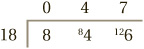

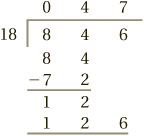

The difference is that as the numbers involved become larger we may have to carry more than one digit at a time to the next column. So calculating the remainders becomes more cumbersome. Rather than cluttering up the division, the remainders are written underneath instead. So, if we wanted to calculate 846 ÷ 18, short division would look like this:

while long division occupies a little more space:

What is the meaning of the column of numbers underneath?

Since 18 cannot divide the 8 in the hundreds column, we carry the 8 and move on to the next column. The only difference is that we write the 84 underneath this time. Then 18 goes in to 84 four times, since 4 × 18 = 72, but 5 × 18 = 90 which is too big. So 4 is written on top, just as before, and 72 is written below 84 and then subtracted from it to find the remainder, 12.

If we were doing short division, 12 would be the number we carry to the next column and stick in front of the next digit. But because we are doing things underneath, we bring down the next digit from 846 (namely 6) and stick it on the end of the 12 to get 126. The last step is to try to divide 126 by 18. A little chunking shows that 18 fits in exactly 7 times, so 7 is written on the top, to complete the calculation.

Dare you try long division? Don’t be put off by the numbers underneath: if you’re not sure what you should be writing down there, try laying the whole thing out as a short division, and doing any supplementary calculations you need underneath. Remember: the working underneath is intended to help you with the calculation, not to confuse you!

IF YOU’VE GOT THE NERVE, TRY QUIZ 6!

Sum up There are several methods for bringing division down to earth. But even long division is manageable, once you have a good grasp on remainders!

1 Times tables, backward!

1 Times tables, backward!

a 4 ×  = 12

= 12

b 5 ×  = 30

= 30

c 3 ×  = 27

= 27

d 8 ×  = 64

= 64

e 9 ×  = 63

= 63

2 Write out as remainders and as fractions.

2 Write out as remainders and as fractions.

a 11 ÷ 4

b 16 ÷ 6

c 24 ÷ 7

d 48 ÷ 5

e 59 ÷ 8

3 Chunking

3 Chunking

a 96 ÷ 8

b 154 ÷ 7

c 279 ÷ 9

d 372 ÷ 6

e 8488 ÷ 8

4 Lay these out as short divisions.

4 Lay these out as short divisions.

a 864 ÷ 2

b 770 ÷ 7

c 903 ÷ 3

d 8482 ÷ 2

e 9036 ÷ 3

5 Short division

5 Short division

a 605 ÷ 5

b 426 ÷ 3

c 917 ÷ 7

d 852 ÷ 6

e 992 ÷ 8

6 Long division! Dare you. try it?

6 Long division! Dare you. try it?

a 294 ÷ 14

b 270 ÷ 15

c 589 ÷ 19

d 1785 ÷ 17

e 1464 ÷ 24