• Understanding what negative numbers mean

• Recognizing when negative numbers are useful

• Knowing how to use the “number line”

If the idea of negative numbers does not come naturally to you, don’t worry. You are in good company! It took mathematicians and scientists thousands of years before the concept became respectable. But if you don’t have a thousand years to spare, you needn’t worry either. The principle is quite simple, once the basic idea has been grasped.

The story of negative numbers begins in the world of commerce, and they still demonstrate their great usefulness in trade today.

Imagine that I have set up a business, and am looking back over my accounts at the end of my first month’s trade. There are three basic positions that I might be in. Firstly, if my bank account is overdrawn, that means that I am in debt. Over the month, I have spent more money than I have received. So, how much money do I actually have, at this stage? The true answer is “less than zero.”

The second possibility is that I have broken even. If my expenditure and income have balanced each other out exactly, then the amount of money in my account is zero. I am neither in debt, nor in credit.

The third possibility is that more money has come in than I have spent. In other words, I have made a profit, and my bank account is in credit.

(Of course, this is a simplification from a business perspective, where people generally distinguish between capital investment at the start of a business, and running expenses. Nevertheless, the essential idea is, I hope, reasonable enough.)

In the past, people considered these three separate possibilities as being essentially different. But, over time, the realization dawned that the three could all be represented as different positions along a single scale. Nowadays, we call this picture the number line.

The number line is a horizontal line, with 0 in the middle. To the right of 0, the positive numbers line up in ascending order: 1, 2, 3, 4, … To the left of zero are the negative numbers, which progress leftwards: −1, −2, −3, −4, …

Sometimes is it convenient to put negative numbers inside brackets like this: (−1), (−2), (−3), … There is nothing complicated going on here; it is just to stop the—signs getting muddled up when we start having other symbols around.

Notice that there is no −0. At least there is, but it is the same thing as the ordinary zero: −0 = 0. Every other number is different from its negative, so −1 ≠ 1, for instance.

We might think of this number line as representing my bank account. At any moment, it is at some position along that line. If I am £15 overdrawn, I am at −15. If I am £20 in credit, I am at +20. (It is usual to omit the plus sign, and just write “20,” but sometimes it is useful to include it for emphasis.)

HAVE A GO AT THIS YOURSELF IN QUIZ 1.

For this chapter, we will be focusing on the whole numbers (positive, negative and 0). But between these are all the usual decimals and fractions, which also come in both positive and negative varieties. We shall meet these in more detail in future chapters. But if we want to find  , it is

, it is  of the way from 4 to 5. In the same way,

of the way from 4 to 5. In the same way,  of the way from −4 to −5. (A possible mistake here is to position it as

of the way from −4 to −5. (A possible mistake here is to position it as  of the way from −5 to −4.)

of the way from −5 to −4.)

For years, the principal purpose of numbers has been to count things: 3 apples, 7 children or 10 miles. So, when negative numbers first make their entrance, a natural question is: how can you have −3 apples? I hope that an answer is now plausible: having −3 apples means being in debt by 3 apples.

How does the number line tie in with the usual idea of addition? Well suppose you now go and pick 3 apples. But, instead of adding them to your apple larder, you pay them to the person to whom you owe 3 apples. So, after receiving 3 apples, you end up with none: −3 + 3 = 0. This can be shown on the number line as starting at −3, then moving three places to the right to end up at 0.

It is not just trade where negative numbers are useful. Another example is temperature. In the Celsius (or centigrade) scale, 0 is defined to be the freezing point of water. If we start at 0 degrees and gain heat, we move up into the warmer, positive temperatures. If we lose heat, we move downward into the colder, negative numbers. A thermometer, then, is nothing more than a number line, with a tube of mercury giving our current position on it.

The number line is useful for seeing addition and subtraction at work. If I am at 7, then adding 3 is the same as taking three steps to the right along the number line: 7 + 3 = 10. Similarly, subtracting 3 is the same as taking 3 steps to the left: 7 − 3 = 4.

PRACTISE USING THE NUMBER LINE IN QUIZ 2.

This is not exactly news. But the same principle remains true whatever the starting position. So even if we begin at a negative number such as −5, then adding 3 again means taking three steps right: −5 + 3 = −2. Similarly, subtracting 3 means taking 3 steps left: −5 − 3 = −8.

Above, we saw how to use the number line to add or subtract. But there is still something we need to make sense of: what is the relationship between subtraction and negative numbers? In a sense they are the same thing … but we need to know the details.

The trouble is that we seem to be using the same symbol (−) for two different things: firstly (as in “−3”), this symbol indicates a position on the number line to the left of 0, meaning a negative number; and secondly, to describe a way of combining two numbers, as in “7 − 4.” This second use corresponds to a movement leftwards along the number line.

So what is going on here? You could think of putting a minus sign in front of a number as like “flipping it over,” using 0 as a pivot. So putting a minus sign in front of 7 means 7 flips over, all the way to the far side of 0, and lands on −7. So what then is “− −7,” or “−(−7),” as we might write it? Well, when you flip over −7 you get back to 7. So:

−(−7) = 7

The fact that two minus signs cancel each other out in this way is the key to working with negative numbers.

NOW HAVE A GO AT QUIZ 3.

So when we face questions like “9 − (−3),” the two minus signs cancel out, to give us “9 + 3.” But when we have “9 + (−3),” there is only one minus sign, so it doesn’t get canceled out, and is the same thing as “9 − 3.” This then is the relationship between negative numbers and subtraction:

Subtracting 3 from 9 is the same thing as adding −3 to 9.

Notice that this is not the same as adding −9 to +3.

So much for addition and subtraction. What about multiplying negative numbers? Well to start with, remember that multiplication is essentially repeated addition. So 4 × (−2) should be the same as (−2) + (−2) + (−2) + (−2), which is just −2 − 2 − 2 − 2, that is to say −8.

To think about this in terms of trade, if I lose £2 each day (that is to say, if I “make −£2”), then after four days I have lost £8 (or “made −£8”). This illustrates that when we multiply a positive number by a negative number, the answer is negative. So −5 × 2 = −10 and also 5 × −2 = −10. Similarly, −1 × 4 = −4 and 1 × −4 = −4, and so on.

The most confusing moment in the dealing with negative numbers is when two negative numbers are multiplied together: (−4) × (−2), for example. But we have already seen above how two minus signs cancel each other out, and here it is exactly the same again. Two negative numbers produce a positive result: (−4) × (−2) = 8.

How does this work in terms of trade? Suppose I lose £2 per day (that is to say, I “make—£2”). The question is how much will I have made or lost in −4 days time? Well, “in −4 days time” must mean 4 days ago. And if I have been losing money at a rate of £2 per day, then 4 days ago I must have been £8 richer than I am today, which matches the result above.

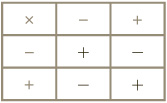

We can put these rules in a little table:

Or more concisely:

GOT IT ? TRY QUIZ 3.

When you have mastered negative multiplication, division is easy! All we need to do is “multiplication backward.” So to calculate (−6) ÷ (−3), we have to solve (−3) ×  = −6. The two obvious possibilities are 2 and −2, but only one can be right, so which is it? Well we know that (−3) × (−2) = 6, which is not what we want. But (−3) × 2 = −6, exactly as we might hope. So the answer is 2.

= −6. The two obvious possibilities are 2 and −2, but only one can be right, so which is it? Well we know that (−3) × (−2) = 6, which is not what we want. But (−3) × 2 = −6, exactly as we might hope. So the answer is 2.

Perhaps surprisingly, the rules for working out the sign for division are the same as for multiplication:

Or more concisely:

TRY USING THESE RULES IN QUIZ 5.

Sum up A number line is a great picture of the world of numbers: positive, negative, and zero.

1 Draw a number line, between −5 and 15. Mark all the whole numbers. Then add in marks for these numbers.

a − and

and

b −1 and −1

and −1

c −  and

and

d −3 and

and

e −4 and 4

and 4

2 Add and subtract on a number line.

2 Add and subtract on a number line.

a 8 + 7 and 8 − 7

b 3 + 3 and 3 − 3

c 3 + 6 and 3 − 6

d −5 + 4 and −5 −4

e −2 + 3 and −2 −3

3 Doubling back

3 Doubling back

a 5 + (−4) and 5 − (−4)

b 2 + (−3) and 2 − (−3)

c 0 − 5 and 0 − (−5)

d −4 −2 and −4 −(−2)

e −3 −5 and −3 − (−5)

4 Times tables go negative

4 Times tables go negative

a 2 × (−3) and (−2) × (−3)

b 4 × (−5) and (−4) × (−5)

c 7 × (−3) and (−7) × (−3)

d 8 × (−4) and (−8) × (−4)

e 25 × (−4) and (−25) × (−4)

5 Division goes negative

5 Division goes negative

a 8 ÷ 2 and 8 ÷ 4 (−2)

b (−18) ÷ 6 and (−18) ÷ (−6)

c 28 ÷ 7 and 28 ÷ (−7)

d (−33) ÷ 3 and (−33) ÷ (−3)

e (−57) ÷ 19 and (−57) ÷ (−19)