• Knowing the names of extremely large numbers

• Being able to write very large and very small numbers

• Understanding the metric system of measurements

There is something special about the number 10. The numbers 0–9 each have their own individual symbol. But when we reach 10 its symbol is made up from those for 0 and 1. This simple observation cuts to the very heart of the modern way of representing numbers. It was not always like this, as anyone familiar with Roman numerals knows.

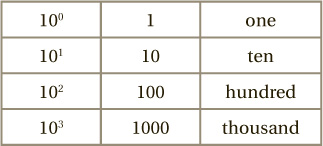

It is not just 10 which is significant, but all the powers of 10. These are 100, 1000, 10,000, 100,000, and so on. These are special in our way of writing numbers, since they mark the points where numbers become longer: while 99 is two digits long, 100 is three, while 999 is three digits long, 1000 is four, and so on.

The number 1000 is 10 × 10 × 10, which, in the language of powers is 103. (See the previous chapter for a general discussion of powers.) The important observation is this: the power of 10, in this case 3, actually counts the zeros. So 103 is the same as 1 followed by three zeros. This becomes very useful as the numbers get larger. The expression 1010 can be read and digested much more easily than if you were left to count the zeros yourself: 10,000,000,000.

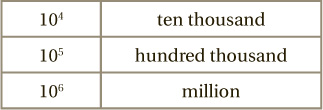

Powers of 10 are also the points where new names for numbers appear. If we scroll down the powers of 10, the first few are simple enough:

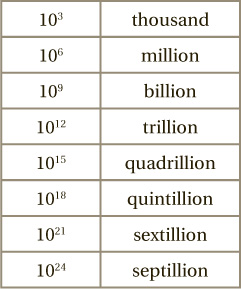

After a thousand, new names appear every three steps, with ten and a hundred filling the intermediate gaps. So:

It’s the multiples of three which are important from the point of view of naming numbers.

A word of caution here: in the past there was some disagreement across the Atlantic about what constituted a “billion.” Americans have always considered a billion to be a thousand million (that is, 109) while the British used to use the same word to mean a million million (that is, 1012). That is no longer the case. Today, the system above is universal in the English-speaking world. However, the disparity is worth remembering, if you are ever reading British documents dating from before 1974. In other languages, systems vary. In French, for example, 106 is un million, 109 is un milliard, and 1012 is un billion. In Japanese, Chinese and Korean, the basic unit is 104 rather than 103 with new numerical names appearing at 104, 108, 1012, 1016, and so on. Translators beware!

COUNT THOSE ZEROS! TRY QUIZ 1.

Often when we see numbers written down, there are a few letters after them: for example, 5kg, 10s, 12cm. These letters are different from the ones that appear in algebra (see Algebra). Instead these are units, and their purpose is to define exactly what the numbers are measuring, whether that be mass, time, distance or something else, and the scale being used to measure it.

There is a whole army of units that people use to measure everything from humidity (g/m3, that is, grams per cubic meter) to the spiciness of chilies (SHU, that is, Scoville heat units). It would not be practical or useful to attempt a complete list!

Nevertheless, there is something important to say about the way that a certain class of unit relates to the powers of 10 we have just been looking at. This is known as the metric system, and it is based on meters for distance (rather than inches or miles), grams for weight (rather than ounces or stones), seconds for time (rather than minutes or years). Other units are then built out of these. A liter, for example, is 100cm3 (see Area and volume), while the standard measure of force is the Newton, defined to be 1kg m/s2.

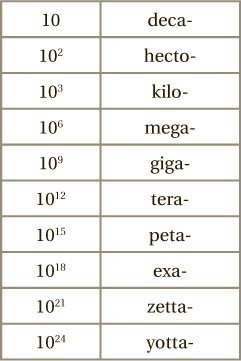

Let’s take an example, to see how the system works. A gram is a unit of weight. One gram on its own is not very much. So if we want to measure people, cars or planets, a gram doesn’t seem a very satisfactory starting point. However, there are prefixes which can be put in front of the word “gram,” to make the unit bigger. One is “kilo” which means a thousand. So 1 kilogram is the same thing as 1000 grams. The kilogram is a sensible unit for measuring the mass of a person, for example. Just as with the names of numbers, new metric prefixes generally occur every multiple of 3:

Many modern scientists might frown at the first two in this list, but mechanical engineers do sometimes discuss force in terms of decanewtons (daN), while meteorologists occasionally measure atmospheric pressure in hectopascals (hPa). But it is for larger numbers that the system really becomes useful. It is very common to measure distances in kilometers (km), and the resolution of a digital camera might be 5 megapixels (MP), meaning that it contains 5 million individual image sensors (pixels).

Unless you are an astrophysicist measuring the weight of stars, the largest of these prefixes you will probably ever need is ‘tera-‘, or 1012. It is quite common for computers to have 1 terabyte (TB) disk drives now.

If you wanted to measure the weight of a car, the megagram would be a sensible unit to use. It just happens that the megagram more commonly goes by the name of ton, meaning a million grams, or equivalently, a thousand kilograms.

IF YOU KNOW YOUR PREFIXES, HAVE A GO AT QUIZ 2!

Everything we have said for the very large goes equally well for the very small. We can use negative powers of 10 to represent small numbers. To start with, 10-1 means  , or equivalently 0.1. Similarly, 10-2 is

, or equivalently 0.1. Similarly, 10-2 is  . which is

. which is  , or 0.01, and 10-3 is

, or 0.01, and 10-3 is  which is

which is  , or 0.001, and so on.

, or 0.001, and so on.

A quick rule, as before, is that the negative power counts the number of zeros, with the important caveat that a single zero before the decimal point must be included in the count. With this said, it is easy to see that 10-6 is one millionth, 10-9 is one billionth, and so on. Writing these in decimals, we get 10-6 = 0.000001 and 10-9 = 0.000000001.

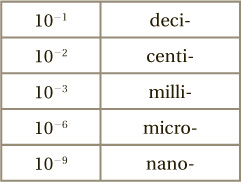

There are also metric prefixes for the small numbers:

NOW HAVE A GO AT QUIZ 3.

Again the first of these is less commonly used than the second and third, although the standard measure of loudness, the decibel, was originally defined as one tenth of a bel (a unit which has long since fallen out of favor). We commonly use a centimeter (cm), which is a hundredth of a meter, and a milliliter (ml), which is one thousandth of a liter. A pill might contain 5 micrograms µg) of vitamin D, and we have all heard the hype surrounding nanotechnology, meaning engineering which takes place on the scale of nanometers (nm). Getting very small, 3 picoseconds (ps) is the time it takes a beam of light to travel 1 millimeter.

Metric prefixes and funny names like “sextillion” are sometimes useful, and are good fun. But actually, with powers of 10 at our disposal, they are not strictly necessary.

Your calculator, for instance, can function perfectly well without them. Type in two large numbers to be multiplied together, perhaps 20,000,000 × 80,000,000. How does your calculator display the result? Mine displays “1.6 × 1015”. We could translate this as 1,600,000,000,000,000 or “1.6 quadrillion.” But actually the expression “1.6 × 1015” is shorter and easier to understand than either of these. My calculator is taking advantage of powers of 10, to express this very large number in an efficient and compact way: 1.6 × 1015. This way of representing numbers is known as standard form.

It is an essential skill to be able to move back and forth between standard form and traditional decimal expressions, and that is the final topic we shall explore in this chapter.

In technical terms, a number is in standard form if it looks like this: A × 10B, where A is a number between 1 and 10 (not necessarily a whole number), and B is a positive or negative whole number. An example is 3.13 × 104. Let’s translate this back into ordinary notation. Above, we saw that the power of 10 can correspond to the number of zeros on the end (so 103 = 1000 for instance). This is fine when we are considering 1 followed by a line of zeros, but 3.13 is not like this. We now need a slightly more sophisticated perspective. The answer comes from the chapter on multiplication, where we saw that multiplying by 10 corresponds to shifting the digits one step to the left with respect to the decimal point. So multiplying by 104 is equivalent to shifting to the left four times: 3.13 → 31.3 → 313.0 → 3130.0 → 31300.0

That final number, 31,300, is our answer. (This should not come as a surprise, since 104 = 10,000 and 31,300 is 3.13 lots of 10,000.) Another way to think of this is that the 104 tells us the length of the number. Just as 104 is 1 followed by four zeros, so 3.13 × 104 will be 3 followed by four other digits (of which the first two are 13).

When the power of 10 is negative, as happens in 2.83 × 10-4, we have to shift the digits right instead of left: 2.83 → 0.283 → 0.0283 → 0.00283 → 0.000283

In this case, it is actually easier to jump straight to the final answer, since the negative power (4 in this example) simply counts the zeros to be stuck on the front, including one zero before the decimal point as usual.

TRANSLATE NUMBERS FROM STANDARD FORM IN QUIZ 4.

We have seen how to translate standard form into ordinary decimal notation. Now let’s go in the other direction. Suppose I want to express 2000 in standard form. That’s easy enough: since 2000 consists of two lots of 1000, or 103, it is equal to 2 × 103. This is now in standard form.

Let’s take another example: 57,800. The definition of standard form dictates that the answer must look like 5.78 × 10?. The only question is: what will the power of 10 be? Well, how many times would we need to shift the digits?

5.78 → 57.8 → 578 → 5780 → 57,800

There are four rightward shifts there, so the answer must be 5.78 × 104. Alternatively, we could just notice that the original number is a 5 followed by 4 other digits.

The principle is the same for small numbers, such as 0.0000997. Again the standard form representation will be 9.97 × 10-?. We just need to know the negative power of 10. It turns out that five rightward shifts are needed:

9.97 → 0.997 → 0.0997 → 0.00997 → 0.000997 → 0.0000997

Alternatively, we could observe that there are five zeros at the beginning of the number (including the one before the decimal point). So the answer is 9.97 × 10-5.

NOW HAVE A GO YOURSELF IN QUIZ 5.

Using standard form, we can measure any distances in meters. For instance, the distance to the Sun’s nearest neighbor, Proxima Centauri, is around 4 × 1016 meters. We could write this as 40 petameters, but this might raise a few eyebrows, although it is perfectly correct. (It would be more usual to say 4.2 light years, with one light year coming in at just under 10 petameters.) But actually, “4 × 1016 meters” is already a perfectly good description.

Similarly we can measure geological timescales in seconds, if we like: the Jurassic era began around 6.3 × 1015 seconds ago.

Sum up Powers of 10 are extremely convenient for writing down very large or very small numbers!

1 Write these numbers out in full.

a 7 million

b 8 billion

c 9 trillion

d 10 quadrillion

e 11 quintillion

2 Express these quantities using suitable prefixes.

a A distance of 18,000 meters

b A computer screen containing 37,000,000 pixels

c A blood cell which weighs 0.000000003 grams

d A steam-hammer which exerts a force of 900,000 newtons

e A music player whose memory is 8,000,000,000 bytes

3 Convert these numbers to words (such as a millionth) and also decimals (such as 0.000001).

a 10-3

b 10-2

c 10-5

d 10-7

e 10-12

4 Convert these standard form numbers to ordinary decimal numbers.

a 6 × 105

b 2.1 × 104

c 8.79 × 10-6

d 1.332 × 10-3

e 6.71 × 1010

5 Write these numbers in standard form.

a 800,000

b 56,000

c 0.00062

d 987,000,000

e 0.00000000111