• Understanding what roots are and what they are useful for

• Getting to grips with what logarithms actually mean

• Knowing how to switch between the language of powers, roots and logs

A number, when squared, produces 9. What is that number? We could write this question as?2 = 9. So long as we remember what squaring means (see Powers if you don’t!), the answer should be obvious: 3 squared is 9 (32 = 3 × 3 = 9), so the answer is 3. In this chapter, we will be interested in this process of squaring backward. The technical term for this is square-rooting. So we say that 3 is the “square root” of 9.

There are various ways to write a square root: the commonest is to use the symbol  . (Don’t get this confused with the symbols sometimes used to write out long division.) So we would write

. (Don’t get this confused with the symbols sometimes used to write out long division.) So we would write  .

.

IF THAT SEEMS CLEAR, THEN HAVE A GO AT QUIZ 1.

The easiest way to figure out a square root is to flip the question round, to talk about squaring instead. So if we’re asked to calculate , the answer is going to be the number which when squared produces 49. So we need to solve?2 = 49.

, the answer is going to be the number which when squared produces 49. So we need to solve?2 = 49.

This question is easy enough (I hope!). But in most cases, the square root of a whole number will not itself be a whole number. In such cases, you will need to use a calculator to get at the answer, and there is a dedicated button  to do the job. So, to calculate

to do the job. So, to calculate  , you would need to type

, you would need to type

, to arrive at an answer of 3.87 (to two decimal places).

, to arrive at an answer of 3.87 (to two decimal places).

It is not only squaring which has a corresponding root. We can ask exactly the same thing for other powers. For example, if a box is cube-shaped and has a capacity of 64cm3, how wide is it? Well, the volume of the box must be the width cubed (that is, multiplied by itself three times). So what we want is the number which when cubed gives 64, that is, ?3 = 64. This amounts to finding the cube root of 64. The answer is 4 because 43 = 4 × 4 × 4 = 64. We write this as  , introducing a little 3 to the root symbol.

, introducing a little 3 to the root symbol.

Then the same thing works for all higher powers too. We could ask for the fourth root of 81, or  , meaning the number which when it is multiplied by itself four times gives 81.

, meaning the number which when it is multiplied by itself four times gives 81.

According to this rule, where a cube root is written as  , and a fourth root as

, and a fourth root as  , the square root symbol

, the square root symbol  could equally well be written as

could equally well be written as  . But, because it is the commonest root, it is usual practice to leave out the little “2.”

. But, because it is the commonest root, it is usual practice to leave out the little “2.”

Most roots of most numbers do not produce a whole number as the answer. So, often, the safest recourse is to use the calculator. But beware: the square root button  does not do the job for higher roots! There is another button for calculating higher roots, which might be indicated by

does not do the job for higher roots! There is another button for calculating higher roots, which might be indicated by  or

or  . You might also need to press the

. You might also need to press the  or

or  key to access this.

key to access this.

So, to calculate  , for, example, you would need to press

, for, example, you would need to press

to arrive at an answer of 1.55, to two decimal places.

to arrive at an answer of 1.55, to two decimal places.

NOW HAVE A GO AT QUIZ 2.

There is another way to write roots, which does not use the root symbol , and which is worth being aware of. We can write roots as fractional powers. Instead of writing

, and which is worth being aware of. We can write roots as fractional powers. Instead of writing  we would write 4

we would write 4 , and instead of

, and instead of  , we would write

, we would write  . Each time, the little number in the root symbol is written underneath a 1 (as a fraction) and then becomes a power.

. Each time, the little number in the root symbol is written underneath a 1 (as a fraction) and then becomes a power.

The advantage to this is that it allows roots and powers to be combined quite easily. For instance, you might want first to take the cube root of 8, and then square the result. This looks cumbersome using the root notation:  . In the power notation this can be written much more neatly as

. In the power notation this can be written much more neatly as  . (This is based on the second law of powers: (ab)c = ab × c: see Powers.)

. (This is based on the second law of powers: (ab)c = ab × c: see Powers.)

When faced with something like  . there are two things happening to the number 16. The little 2, at the bottom of the fraction, indicates not squaring but square rooting. Meanwhile the little 3 (on top of the fraction) indicates cubing (raising to the power of 3). To calculate the answer, we perform both of these steps. First calculate the root

. there are two things happening to the number 16. The little 2, at the bottom of the fraction, indicates not squaring but square rooting. Meanwhile the little 3 (on top of the fraction) indicates cubing (raising to the power of 3). To calculate the answer, we perform both of these steps. First calculate the root  . Next raise that number to the power of 3, 43 = 64. (In fact, the order doesn’t matter, you could equally well calculate the power first: 163 = 4096, and then take the root,

. Next raise that number to the power of 3, 43 = 64. (In fact, the order doesn’t matter, you could equally well calculate the power first: 163 = 4096, and then take the root,  . The fact that the two answers match, and mesh so well with the second law of powers, is what makes this notation very satisfying!)

. The fact that the two answers match, and mesh so well with the second law of powers, is what makes this notation very satisfying!)

TRY SOME FRACTIONAL POWERS IN QUIZ 3.

There are some words in mathematics which strike fear into the soul, conjuring up the image of something unimaginably technical and incomprehensible. One such culprit is the word “logarithm.” But, in truth, logarithms (or “logs” to their friends) are much tamer creatures than their fearsome reputation suggests. They are just the opposites of powers, in the same way that subtraction is the opposite of addition, and division is the opposite of multiplication.

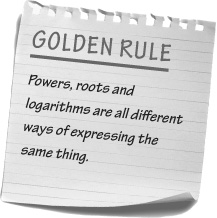

But how can this be true? Aren’t roots the opposite of powers, as we have just seen? Yes they are! And yet roots and logs are not the same thing. In fact, the best picture is to see powers, roots and logarithms as three corners of a triangle.

To answer the question 2? = 8 is to reason about logarithms. In this case the answer is 3, and we say that 3 is “the logarithm of 8 to base 2.” This is written as “log28 = 3.” Although this looks complicated, the meaning of this expression is exactly the same as “23 = 8.”

The key to answering questions about logarithms is to translate them into the more familiar “powers” notation. So, when faced with a challenge such as to find log39, the first step is to translate it into a more comfortable form: 3? = 9. So the question “find log39” just means “how many times do we need to multiply 3 by itself to get 9.” When translating between logarithms and powers, the base of the logarithm (that’s 3 in this example) is the number which gets raised to a power. The challenge is to figure out what the power is.

TRY QUIZ 4—YOU DON’T NEED A CALCULATOR!

As you might expect, many questions about logs need a calculator. But beware! Some calculators have several buttons related to logs, and some have none. A particular warning is that the button simply marked  usually means “log to base 10,” that is, log10.

usually means “log to base 10,” that is, log10.

The general log button is likely to be marked  or

or  . However, not all calculators have this button; on some calculators you cannot calculate general logarithms directly, only those to base 10.

. However, not all calculators have this button; on some calculators you cannot calculate general logarithms directly, only those to base 10.

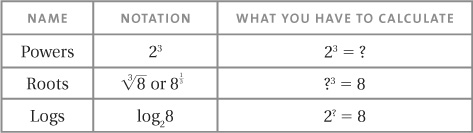

So powers, roots and logarithms are all different perspectives on the same idea, namely expressions involving three numbers, such as 23 = 8. Whether we want to use a power, a root or a log depends on which two numbers are given, and which is left to be calculated.

• You might be asked “23 = ?.” This is a straightforward question about powers.

• If you need to answer “?3 = 8” this is a question about roots, and has the same meaning as  = ?

= ?

• If you are faced with “2? = 8,” that is to say, “log28 = ?,” this is a question about logarithms.

We can put these three possibilities in a table. Whether we want a power, a root or a log is a question of which two of the numbers are given, and which is left to be calculated.

There is one fact about logarithms which made them very useful before the invention of the calculator: when you multiply two numbers together, and then take the logarithm, this is the same as adding the two logarithms of the original numbers together.

To put it another way:

log(x × y) = log x + log y (The law of logarithms)

This is true for any two numbers x and y. I have left the base off the logarithms here because it doesn’t matter what it is, so long as the three logarithms have the same base.

This means that when we are faced with something like log311 + log32, rather than working out the two logarithms separately, we can immediately combine them into a single calculation: log322

This prompts two questions: why should this be true? And who cares?

The reason it is true follows from the first law of powers which we met in an earlier chapter. This says that for any three numbers ab × ac = ab + c. If we take logarithms to base a, we get the law of logarithms.

(For the more ambitious reader, here is the argument: If x = ab and y = ac, then, taking logarithms to base a, it follows that b = log x and c = log y. Also, we know from the first law of powers that x × y = ab+ c. Taking logarithms of this, we get log (x × y) = b + c, which says that log (x × y) = log x + log y.

ENJOY WORKING WITH LOGARITHMS IN QUIZ 5!

The law of logarithms has been remarkably important in the history of science and technology. The reason is that it converts questions of multiplication (which are potentially very tricky), into questions of addition (which are much easier). Before pocket calculators, the standard piece of mathematical equipment was a book of log tables, which listed the logarithms of lots of numbers, to a fixed base (such as 10).

To multiply two large numbers such as 187 and 2012, the procedure was as follows: look up the logarithm of each number in the book of log tables. (Any base will do, so long as we are consistent with our choice. Let’s take base 10.) These numbers have logarithms 2.27184 and 3.30363, respectively (to five decimal places). Next we add these to get 5.57547. To find the final answer, “undo” the logarithm (that is 105.57547) by looking it up in the log tables to find the number that has this as a logarithm. This gives a final answer of 376,244. You can check that this is correct!

Sum up Powers, roots and logarithms are close cousins. If you understand one, you understand them all, so long as you can remember how they are related!

1 Find these square roots.

1 Find these square roots.

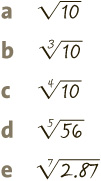

2 Use a calculator to work these out to two decimal places.

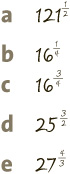

3 Work out these fractional powers.

3 Work out these fractional powers.

4 Find these logarithms.

4 Find these logarithms.

a log636

b log381

c log464

d log2128

e log5125

5 Simplify these logarithms (to get a single answer such as log1112).

5 Simplify these logarithms (to get a single answer such as log1112).

a log46 + log48

b log313 + log32

c log109 + log108

d log57 + log56

e log611 + log610