• Realizing what it means when letters appear in equations

• Understanding how algebra can represent real-life situations

• Learning the rules for working with algebra

For many people, the moment when mathematics moves from being fairly simple to being incomprehensible is when letters start appearing where previously there were only numbers. This is algebra. In this chapter we will have a look at it. We’ll see what it means, and how to do it without getting confused. Most importantly, we will see why it is useful.

Let’s start with an example. Suppose a restaurant bill comes to $40, and is to be divided between 8 people. What calculation do we have to do to work out how much each diner pays? The answer is  . But what if there were only 6 people? Then the answer is

. But what if there were only 6 people? Then the answer is  . And what if the bill was actually $140? Then the calculation is

. And what if the bill was actually $140? Then the calculation is  . Each of these produces different answers: as the numbers we put in change, so do the numbers we get out.

. Each of these produces different answers: as the numbers we put in change, so do the numbers we get out.

Yet there is a sense in which they are actually all the same calculation. Each time, the total bill is divided by the number of diners. We could write this as:

This has an advantage over the previous versions as it makes explicit what is going on, what principle is being applied here. So if the numbers are altered, because of a miscount, or an item being missed from the bill, the same idea continues to work.

Here’s another example. Suppose I am cooking dinner for a group of people. How many baked potatoes do I need? I reason that each adult diner will eat 2, and each child will eat 1, and that I should have 5 as spares in case anyone wants a second helping. This rule comes out as: Potatoes = 2 × Adults + Children + 5. Then, when the numbers of guests have been clarified, I can put this principle into action. Once I know that there will be 5 adults and 3 children, I can plug these numbers into my rule to arrive at 2 × 5 + 3 + 5 = 18 potatoes.

The discussion so far gives us the idea of algebraic formulae. Even if you wouldn’t usually write these sort of rules down as I have done above, I hope you agree that this type of thinking is quite normal and natural.

Well, this is algebra. The only difference when experts do it is that, instead of writing words in their mathematical expressions, they usually cut down to single letters. What is the point of this? To make things neat and tidy, and to save space, of course! (It has not always been thus: mathematicians of bygone eras often wrote lengthy prose in amongst their equations.)

So, in the potato calculation above, I might begin by calling the number of adults a and the number of children c. Then the number of potatoes I need to cook (call it p) must satisfy:

p = 2 × a + c + 5

It is usual to omit the × signs when writing algebra using letters, so we would write this as:

p = 2a + c + 5

What we have arrived at is a typical example of an equation, or a formula. The power of this method is that it expresses lots of different facts in just one line.

Many mathematical facts are expressed in this sort of way. For example, the area of a rectangle is expressed by multiplying its length by its width. We might write this rule as A = l × w (where A, l and w stand for the area, length and width, respectively).

The ability to translate between algebraic formulae and English sentences is one of the central planks of mathematical thinking, and well worth spending some time on.

TURN STATEMENTS INTO ALGEBRAIC FORMULAE IN QUIZ 1.

We have seen how to turn English sentences into mathematical formulae. What can we do with these formulae? When all is said and done, we are probably hoping for a number at the end of the calculation, rather than a collection of letters and algebraic symbols.

To extract a number from a formula, we first need to know how to feed numbers into it. If we have the formula p = 2a + c + 5, and we are further told that a = 5 and c = 3, then we can replace the symbols a and c with these new values, and then work out the value of p:

p = 2 × 5 + 3 + 5 = 18

What we have done here is to substitute numerical values for some of the letters, and then work out the final answer.

We also saw above that a rectangle’s area is given by the formula A = l × w. If a particular rectangle has values of l = 8cm and w = 3cm, then we can substitute these values into the formula to get an area of A = 8cm × 3cm = 24cm2.

HAVE A GO AT SUBSTITUTING VALUES INTO FORMULAE IN QUIZ 2.

The ability to substitute values into formulae becomes more and more important in all branches of the subject, as the mathematics becomes more complex. You might object to the previous examples by saying “multiply the length by width” is quick and simple enough, and doesn’t really need to be abbreviated as a formula. But if we want to calculate the volume of a cone (see Area and volume), the formula “ ” is a lot more concise (and, with practice, easier to read) than writing “to find the volume, multiply the radius of the base circle by itself, and then by the length of the cone, then divide by 3, and multiply by the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter.”

” is a lot more concise (and, with practice, easier to read) than writing “to find the volume, multiply the radius of the base circle by itself, and then by the length of the cone, then divide by 3, and multiply by the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter.”

There are various rules that we can use to make formulae simpler. (These will be invaluable when we come to solve equations later.)

The idea is very familiar, when expressed in terms of numbers: just as we can add up 2 + 3 = 5, similarly we can add 2x + 3x = 5x and 2a + 3a = 5a when letters are involved.

Why should this be so? Think of a number and double it. Then add on your original number tripled. The answer is five times your original number. Magic! Hardly. This will always work, irrespective of what number you choose, and this is the rule expressed by 2x + 3x = 5x. The x, as we have seen, is standing for any number.

This rule is useful for tidying up, or simplifying, algebra. If we have an expression such as:

2 + 3x + 5x + 2 + 2x

then it can be simplified by collecting together the plain numbers: 2 + 2 = 4 and collecting together the xs: 3x + 5x + 2x = 10x, to leave us with a much tidier expression: 4 + 10x.

The same thing works when there are more letters involved. If we are presented with a + 4 + 2b − 5 + b + 3a, then we can gather the plain numbers together: 4 − 5 = −1, and the as: a + 3a = 4a and the bs: 2b + b = 3b, giving a result of 4a + 3b − 1.

Warning! Simplifying algebra is always a good idea, where possible. But one of the commonest mistakes is to try to simplify things where it cannot be done. For example, while b + 2b can be simplified to 3b, if we are faced with the expression b + b2, there is no way to simplify this. It is not equal to 2b or 2b2. (Why not? Well, if b = 10, then b + b2 = 110, while 2b = 20, and 2b2 = 200.) Similarly if we have a + b + ab, this cannot be simplified, and should be left as it is.

SIMPLIFY SOME ALGEBRA IN QUIZ 3.

Here’s a trick: Think of a number, any number! Now add 4, and then double what you get. Now add 2. Next, halve the result, and then subtract the number you first thought of. And the answer is … 5. Alakazam!

How does this work? It is a simple consequence of the algebra of brackets, which is what we are going to look at in the final section if this chapter. We’ll see a detailed explanation later on!

Brackets are useful for avoiding ambiguity when writing out calculations (see The language of mathematics). But they are even more important when algebra is involved.

The key insight is this. Suppose I add 3 to 5 and then double the answer. We might write this as 2 × (3 + 5). It is no coincidence that this comes out the same as doubling 3 and 5 individually, and then adding together the two results: 2 × 3 + 2 × 5.

In fact, this is exactly the principle used for doing long multiplication: that 10 × (50 + 2) is the same as 10 × 50 + 10 × 2. We call this expanding brackets. The idea is as follows: when you have something being added (or subtracted) inside a pair of brackets, and something outside the brackets multiplying (or dividing) the brackets, this is the same as performing the multiplications (or divisions) individually, and then adding up the answers.

In algebra, we might write a × (b + c) = a × b + a × c. Using the convention of omitting multiplication signs, this becomes a(b + c) = ab + ac. The great thing is that this is true whatever a, b and c are.

So, if we are faced with 2(x + 3 y), we expand the brackets to get 2x + 6 y. Similarly x(x − 3y) = x2 − 3xy. These are both just special cases of the general rule.

Let’s go back to the trick we started the section with, and let’s call the mystery number x. The first instruction is to add 4 to it, giving x + 4. Doubling that produces 2(x + 4). At this stage, let’s expand this brackets: 2x + 8. Adding on another 2 gives us 2x + 10. Next we were told to halve the result, which we can write as  , and again, let’s expand the brackets, producing x + 5 The final instruction was to subtract the number we first thought of, which of course is x. But now it is as clear as day that subtracting x from x + 5 will always leave us with 5. It’s not so much Alakazam as Algebra!

, and again, let’s expand the brackets, producing x + 5 The final instruction was to subtract the number we first thought of, which of course is x. But now it is as clear as day that subtracting x from x + 5 will always leave us with 5. It’s not so much Alakazam as Algebra!

EXPLORE THE ALGEBRA OF BRACKETS IN QUIZ 4.

Why not try coming up with some of your own tricks along these lines?

Sum up Algebra is a great language for expressing general rules and laws. Just remember how to translate between algebra and English!

1 Turn these statements into algebra.

a The number of animals on the ark is twice the number of species on Earth. (Let a be the number of animals on the ark and s be the number of species on Earth.)

b The amount of cake on my plate (c) is two divided by the number of people present (p).

c The number of hours to cook the meat (h) is one quarter of its weight in pounds (w) plus an extra half-hour.

d The number of patients in the hospital (p) is four times the number of doctors (d) plus the number of wards (w).

e The temperature in Fahrenheit (F) is the temperature in Celsius (C), multiplied by nine, divided by five, and then with thirty-two added.

2 Substitute the values into the formulae.

a If B = t − s, then what is B when t = 13 and s = 5?

b If  , then what is x when y = 108?

, then what is x when y = 108?

c If  , then what is a when b = 4?

, then what is a when b = 4?

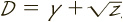

d If  , what is D when y = 10 and z = 16

, what is D when y = 10 and z = 16

e If z = x2y, what is z when x = 6 and y = 2?

3 Simplify these.

a a + 3a

b b + 5 + 2b − 4

c x + 4y + 2x − 2y

d 5x + 5 + x − 3a − 5

e x + 3z + 2y + 2z + 2

4 Expand these brackets.

a 4(x + z)

b 2(x + 4)

c x(x − 1)

d x(x − 2y)

e 2x(x − 2y)