• Recognizing different types of triangle

• Reasoning about a triangle’s angles

• Calculating a triangle’s area

Two straight lines do not make a shape. But three do. This is why the triangle is one of the most important figures in geometry: it is one of the simplest.

But is the geometry of triangles useful? The answer is yes, as the world is full of triangles, even if most of them are invisible. What, you may ask, are invisible triangles? Whenever you choose three points in space, you have defined a triangle. For instance, I might pick the place where I am standing, where my wife is sitting, and the television in the corner of the room. These three points form a triangle.

In any such situation, the techniques in this chapter can apply, even when the triangle’s sides are not immediately obvious. For this reason, triangular geometry really is everywhere, and we shall be meeting more of it later (see Pythagoras’ theorem and Trigonometry).

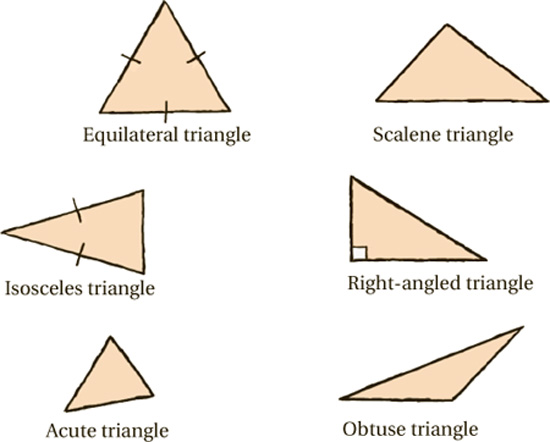

For many people, one triangle is much the same as any other. But, to the connoisseur, triangles come in a variety of forms, each with their own characteristics. The most symmetrical triangle is the one where the three sides are all the same length. Triangles like this are called equilateral (coming from the Latin for “equal sides”).

It automatically follows that the three angles inside an equilateral triangle must also be equal. As we shall see shortly, each of these angles is equal to 60°. So an equilateral triangle has a very rigid shape, with no room for maneuver. The only possible variation is in the triangle’s size. In all other respects, every equilateral triangle looks the same, in much the same way that all squares look the same. In fact the equilateral triangle and the square are the first two regular shapes, meaning shapes whose sides and angles are all equal. We shall explore this further in Polygons and solids.

A slightly less symmetric type of triangle is one which has two of its lengths the same. Such a triangle is known as isosceles (coming from the Greek for “equal legs”). There is more room for maneuver with isosceles triangles: they can look very different, as we shall see shortly.

Most triangles are neither equilateral nor isosceles, but have three sides of different lengths. There is a word for this too: scalene (from the Greek for “unequal”). These words—equilateral, isosceles and scalene—refer to the lengths of the triangle’s sides. But triangles can also be described by the sizes of their angles. A right-angled triangle is, unsurprisingly, one which contains a right-angle. That is to say one of its three angles is equal to 90°. (These are in some ways the “best” triangles, and we will be hearing a lot more about them in Pythagoras’ theorem and Trigonometry.)

GOT THE JARGON? THEN TRY QUIZ 1.

Triangles whose angles are all less than 90° are called acute triangles. (Remember from the previous chapter that an angle less than 90° is called an acute angle.) Similarly, a triangle which contains an obtuse angle (that is to say one that is more than 90°) is known as an obtuse triangle.

That’s a large amount of jargon to digest, and all just to describe different sorts of triangle!

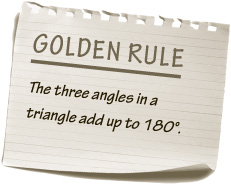

The starting point for the geometry of triangles is a relationship between the three angles inside the triangle. Try drawing a triangle which contains two right angles, or two obtuse angles. You will fail. Why? The answer is given by this chapter’s golden rule.

This rule puts a limit on the possible sizes of the angles inside any triangle.

It will prove useful for calculating the sizes of angles in triangles. But why should it be true? It is worth seeing a proof of this famous fact, since it is not complicated. Indeed, it follows from the facts about angles and parallel lines that we saw in the previous chapter.

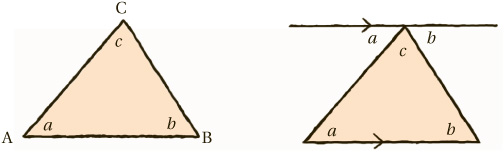

We begin by taking a triangle, call it ABC, meaning that the three corners are named A, B and C respectively. (These are just labels so that we can refer to them individually.) At each corner is an angle. Since we don’t know their values, we had better name these too. Let’s call them a, b and c. So what we want to show is that a + b + c = 180°.

EXPLORE ANGLES IN A TRIANGLE IN QUIZ 2.

We also have the three lines of this triangle, which we might call AB, BC and CA, where AB is the line running from corner A to corner B, and so on.

The main move in the proof is this: we add in a new line, parallel to AB, which passes through the point C.

Now there are now three angles fanning out around C. What is more, these three angles must add up to 180° as they are angles on a straight line, in the terminology of the previous chapter.

The middle angle c is unchanged. The insight is that one of the other two is actually equal to a; this follows from the rule of alternate angles (or “Z angles”) that we saw in the last chapter. By exactly the same reasoning, the third angle must be equal to b. Now we have finished! The three angles at C are a, b and c, but these are angles on a straight line, and so a + b + c = 180°.

Now that we know the three angles in a triangle always add up to 180°, we can use this to perform some calculations.

To start with, if we know two angles of a triangle, we can always work out the third. For instance, if a triangle contains angles of 30° and 45°, then the final angle must the number which when added to 30° + 45° gives 180°. That is to say the final angle must be 180° − 30° − 45° = 105°.

In some cases we can do better than this. If the triangle is equilateral, then we know immediately that all three angles are equal. So it follows that each must be 180° ÷ 3, that is, 60°.

Similarly, if a triangle is isosceles, we can often work out its angles quite quickly. In isosceles triangles, two of the three angles are equal. So now we just need to be given one to work out the others. Suppose ABC is an isosceles triangle where the lengths AB and AC are the same. As usual, we’ll call the three angles a, b and c. It follows that the angles at B and C must also be equal, that is to say, b = c. Suppose we are now told that b = 55°. Then we know immediately that c = 55°. Finally we can work out angle a. It is 180° − 55° − 55° = 70°.

TRY THIS YOURSELF IN QUIZ 3!

We are now going to look at the area of triangles, that is, how much space there is inside them. (We will study area more generally in Area and volume.)

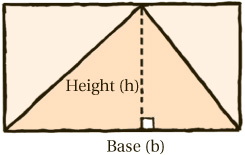

There is a nice rule for calculating the area of a triangle: multiply the base of the triangle by its height, and then divide by 2. So the formula is:

Or, if we call the area A, the base b and the height h, the formula becomes:

This rule is very convenient, and easy to use. But it comes with a few words of warning nevertheless!

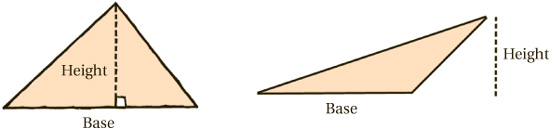

Firstly what do these terms mean? What is the “base” of a triangle? It is the side which runs along the bottom. All right, but here’s something to think about: if we spin the triangle around, it will take up the same amount of space. So the area won’t change. But the base does change! The edge which was at the bottom is no longer the base and one of the other sides takes its place.

So what’s going on? In fact, any of the three sides will do as the “base.” So this is really three formulae in one, depending on which side you pick.

Let’s suppose we have chosen one side as the base. Now, what is the “height”? This is where mistakes often get made! The height is the vertical distance from the base to the top corner of the triangle. That sounds reasonable, I hope, but beware:

Warning! The triangle’s height may not coincide with any of its edges!

Only in right-angled triangles is the height of the triangle the length of one of its sides. In all other triangles it isn’t. The rule is that the height must always be measured at right angles to the baseline: it is the vertical height from the baseline to the top corner. In fact, the height-line may not even be inside the triangle, as this picture shows!

CALCULATE THE AREAS TRIANGLES IN QUIZ 4.

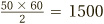

Let’s have an example. Suppose I have decided to look for a house to buy, in the region between three towns: Asham, Bungleside and Cowentry (A, B, C). The question is: how large is the area I have to search? Using a map, I measure the distance from A to B as 50 miles. Taking this as the base, then the height must be the perpendicular distance from the line AB up to the third corner C. The map says that this is 60 miles. So the area of my triangle is  square miles.

square miles.

The formula for the area of a triangle is undeniably useful. But why is it true? Have a look at the triangle below. There is the baseline (b), and a height-line (h). Notice that the height-line divides the shape into two smaller triangles. (As it happens, these are both right-angled triangles.)

Now, we can fit the whole triangle inside a rectangle. What is more this rectangle has the same basic dimensions as our triangle. Its height is h, and its width is b. So the area of the rectangle must be b × h. (See Area and volume for more on this.)

What I want to show is that the triangle takes up exactly half the space inside the rectangle. Why? Well, look at the two little triangles. There is an exact copy of each of them inside the rectangle. So the rectangle is divided into four triangles: two copies of each of the two small triangles, of which one is inside and one outside the original triangle. So the original triangle is exactly half of the rectangle, and its area must be , as expected.

, as expected.

Sum up Triangles are the simplest shapes you can build with straight lines. But triangles can look very different! Luckily, there are some elegant rules for finding their angles and their areas.

1 Draw a triangle, as accurately as possible and reasonably large, to fit each of these descriptions.

a An equilateral triangle

b An isosceles right-angled triangle

c A scalene obtuse triangle

d An isosceles acute triangle

e An isosceles obtuse triangle

2 Measure all the angles of each of the triangles you drew in quiz 1. Check that the three angles sum to 180°.

3 Sketch the triangles and calculate the angles.

a If a right-angled triangle also contains an angle of 30°, what is the third angle?

b ABC is a triangle where the angle at A is 120°, and the angle at B is 45°. What is the angle at C?

c ABC is an isosceles triangle, where AB = AC. The angle at B is 70°. What are the other two angles?

d ABC is an isosceles triangle, where AB = BC. The angle at B is 70°. What are the other two angles?

4 Sketch these triangles and calculate their areas.

a A triangle with base 2cm and height 1cm

b An acute triangle with base 2cm and height 2cm

c A right-angled triangle with shortest sides of 3cm and 4cm.

d A triangle in which the longest side is 5cm, and the perpendicular height from that side is 1cm

e A triangle whose base is 6cm and height is 3cm, where the height-line runs outside the triangle