• Understanding what Pythagoras’ theorem means

• Knowing how the theorem can be used to calculate lengths

• Recognizing how right-angled triangles are used in the wider world

Living in Greece in the sixth century BC, Pythagoras was one of the most famous mathematicians of the ancient world. The theorem which bears his name is one of the first great facts of geometry. Actually it is a matter of debate whether this theorem can be attributed to him personally rather than the group of thinkers whom he inspired, the Pythagoreans. The theorem may even have been known to earlier geometers in India or Egypt.

Leaving the history aside, whoever first proved it, Pythagoras’ theorem is about triangles, those friendly three-sided creatures that we met in an earlier chapter. Specifically, it is about right-angled triangles. These are in many ways the most interesting triangles.

To start with, what is a right-angled triangle? Very simply, it is a triangle which contains a right angle. That is to say, one of the three angles in the triangle is equal to 90°. We can also see a right-angled triangle as half of a rectangle which has been sliced in half diagonally. This perspective will be useful later on.

The main fact we discovered in Triangles was about the angles in a triangle. Pythagoras’ theorem describes a relationship between the lengths of the three sides of a right-angled triangle (not any other kind of triangle). Let’s call the three lengths a, b and c, where c represents the longest side. In a right-angled triangle, the longest side is always the one opposite the right angle. It even has a fancy name: the hypotenuse.

Pythagoras’ theorem describes a relationship between the squares of the three sides, that is, the numbers you get by multiplying each length by itself: a × a, b × b and c × c, or a2, b2 and c2, for short. (See Powers for more discussion of squares and higher powers.)

Pythagoras tells us is that if we add the squares of the two shorter sides, we get the square of the longest side. Putting this in algebraic terms:

There is a famous geometric picture, which illustrates this fact (see right).

The point is that the areas of the two smaller squares (a2 and b2) together add up to the area of the largest square (c2). But what does this mean in practical terms—how can we use it?

How can we calculate actual lengths using Pythagoras’ theorem? Let’s take a simple example: a right-angled triangle which is 2cm tall and 2cm wide (so it’s a 2 × 2 square, cut in half diagonally).

What is the length of the third side (the diagonal of the square)? Pythagoras’ theorem tells us that a2 + b2 = c2, and in this particular example a = b = 2, and c is what we want to work out. Substituting a = b = 2 in the formula, we get 22 + 22 = c2. Working out this out, we find that c2 = 4 + 4 = 8.

NOW HAVE A GO AT QUIZ 1.

How to we calculate c if we know c2? The answer is given by the square root that we met in Root and logs. It must be that  . Typing this into a calculator we get the answer: c = 2.83cm, to two decimal places. (Notice that, even though the numbers in the question were whole numbers, the answer isn’t. This is very common.)

. Typing this into a calculator we get the answer: c = 2.83cm, to two decimal places. (Notice that, even though the numbers in the question were whole numbers, the answer isn’t. This is very common.)

Sometimes we might already know the longest side of the triangle, and want to know one of the shorter ones. For instance, suppose a right-angled triangle is 24cm wide with a hypotenuse of 25cm. The question we want to answer is: how high is it? If we call the height a, then the theorem tells us that:

a2 + 242 = 252

Working these squares out, this becomes:

a2 + 576 = 625

Using a technique we met in Equations, we subtract 576 from both sides, to get:

TRY USING PYTHAGORAS’ THEOREM THIS WAY IN QUIZ 2.

Finally, we take the square root of both sides:  , which we might recognize (without using a calculator) as giving a = 7cm.

, which we might recognize (without using a calculator) as giving a = 7cm.

What use is Pythagoras’ theorem? It is not as if we see right-angled triangles every day … or do we?

Actually, it is quite common to want to know the length of a diagonal line when we already have information about horizontal and vertical distances. In such situations, we can get help from hidden right-angled triangles.

For example, suppose a rectangle is 5cm wide and 12cm long. How long is its diagonal? The answer is not obvious, but Pythagoras comes to the rescue, because when we draw in the diagonal, we split the rectangle into two right-angled triangles that have the same length and width as the rectangle. The diagonal of the rectangle is the hypotenuse of the right-angled triangle. So we can use Pythagoras’ theorem. Whatever the length of the diagonal is, call it c, it must be true that:

52 + 122 = c2

Working this out, we get c2 = 25 + 144 = 169. So we want a number which, when squared, gives 169. With or without a calculator, we can identify the answer as c = 13 cm.

Here is another example. Suppose a church tower is 100 meters tall. My wife waves to me from the top, while I sit sipping coffee in a café on the other side of the piazza below, 75 meters away from the base of the tower. How far is my wife from me?

There is a right-angled triangle hidden in this scenario. One edge is provided by the line from me to the base of the church tower, and another is the church tower itself. These are 75m and 100m respectively, and crucially these two are at right angles to each other (assuming that the tower goes straight up and down, not like the leaning tower of Pisa). The third side (the hypotenuse) is now the length we want, because this has me at one end and my wife at the other. Again we call this length c, and Pythagoras’ theorem assures us that:

To solve this, we first work out 752 = 5625 and 1002 = 10,000. Adding these together, we find that c2 = 15,625. So the final step is to take the square root of 15,625, and find that c = 125m.

TRY USING PYTHAGORAS’ THEOREM IN QUIZ 2.

I hope you have seen that Pythagoras’ theorem can be genuinely useful for calculating lengths, whenever a right-angled triangle can be found. But why should it be true? This theorem has been proved in many different ways, probably more than any other theorem in the history of mathematics. Each generation of mathematicians provides a new proof. In 1907, Elisha Loomis assembled a collection of 367 different proofs, but the total number is much higher.

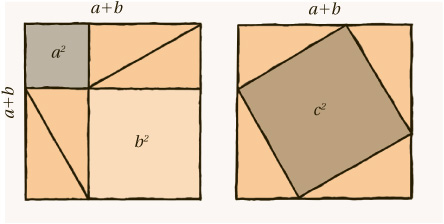

One particularly neat proof was discovered by Bhaskara in 12th-century India. Start with a right-angled triangle with sides of length a, b and c, where c is the hypotenuse as usual. Now we form two large squares, each with side length a + b.

The first large square is divided up inside into four copies of the original triangle, together with one smaller square of area a2 and another square of area b2. The second large square is divided up differently, into four copies of the original triangle and one smaller square of area c2. The crucial observation is that the areas of the two large squares are the same (obviously, because they are identical). In each case, there are four copies of the right-angled (a, b, c) triangle inside; although these are arranged differently, the total area of these four triangles must be the same. That means that the area that is left over in each of the two large squares must be the same. In the first square the area left over is a2 + b2 and in the second square the area left over is c2 so these two quantities must be equal, that is, a2 + b2 = c2.

PLAY AROUND WITH THIS PROOF IN QUIZ 4.

Such a wonderful theorem is worth spending some time thinking about—even if it’s not immediately obvious!

Perhaps the simplest right-angled triangle is half a square. If the square is 1cm wide, then Pythagoras’ theorem tells us that the hypotenuse c satisfies c2 = 12 + 12 so c2 = 2, and it must be that  . It is slightly inconvenient that this is not a whole number. In fact, it is even worse. Like the number π (see Circles),

. It is slightly inconvenient that this is not a whole number. In fact, it is even worse. Like the number π (see Circles),  is an irrational number, meaning that it cannot be written exactly as a fraction, or even as a recurring decimal.

is an irrational number, meaning that it cannot be written exactly as a fraction, or even as a recurring decimal.

This is what usually happens. For example, if you draw a right-angled triangle with shorter sides 1cm and 2cm, the hypotenuse will be  , which again is irrational.

, which again is irrational.

Occasionally, however, we do get a whole number as the answer. If the two shorter sides are 3cm and 4cm, then the hypotenuse is exactly 5cm.

These situations, where all three sides of a right-angled triangle are whole numbers, are known as Pythagorean triples. The first one is 3, 4, 5. If we double all these lengths, we get another: 6, 8, 10. Multiplying all the lengths by other numbers will also produce further Pythagorean triples.

EXPLORE PYTHAGOREAN TRIPLES IN QUIZ 5.

Apart from multiples of 3, 4, 5, the next Pythagorean triple is 5, 12, 13. Pythagorean triples are rather mysterious and unpredictable things!

Sum up Pythagoras’ theorem is one of the great geometrical theorems. It is just a question of putting it to good use!

1 Calculate the hypotenuse (the longest side) of right-angled triangles which have these shorter sides.

a 3 miles and 4 miles

b 1cm and 1cm

c 2 meters and 3 meters

d 5mm and 6mm

e 8km and 15km

2 Calculate the missing side! In each case c is the hypotenuse, and a and b are the shorter sides.

a a = 1mm and c = 3mm

b b = 2 miles and c = 4 miles

c a = 1cm and b = 9cm

d b = 7km and c = 11km

e a = 11 inches and c = 61 inches

3 Calculate these distances (to one decimal place). In each case, you will need to identify a right-angled triangle, and spot which side is the hypotenuse.

a A rectangular room is 4 meters long and 3 meters wide. What is the distance from one corner to the diagonally opposite corner?

b A flag is 38cm wide and 56cm long. A black stripe runs diagonally from one corner to another. How long is the black stripe?

c An airplane flies directly over my friend’s house at an altitude of 10km. I am 1km away from her house. How far is the airplane from me?

d A football pitch is 119m long and 87m wide. If I run from one corner to the diagonally opposite corner, how far have I run?

e A submarine is 300m east of a ship on the sea surface, and is at a depth of 400m. How far apart are the ship and the submarine?

4 a Draw a right-angled triangle. Now try to recreate Bhaskara’s proof using your triangle!

b A right angle triangle has sides of length a = 3cm, b = 4cm, and c = 5cm. Find its area (see chapter on Triangles) and find the areas of the four squares used in Bhaskara’s proof. Check that the proof works!

c In a Bhaskara proof, the four squares have areas of 6.25cm2, 36cm2, 42.25cm2, and 72.25cm2. What are the dimensions of the right-angled triangle?

d In a Bhaskara proof, the largest outer square has an area of 529cm2 and the smallest inner square has an area of 64cm2. What are the dimensions of the right-angled triangle?

5 Use Pythagoras’ theorem to complete these Pythagorean triples.

a 7, 24, ?

b 8, 15, ?

c 9, 40, ?

d 11, ?, 61

e ?, 35, 37