Middlemarch by George Eliot

‘He had two selves within him apparently, and they must learn to accommodate each other and bear reciprocal impediments. Strange, that some of us, with quick alternate vision see beyond our infatuations, and even while we rave on the heights behold the wide plain where our persistent self pauses and awaits us.’

Middlemarch, Book 2, ‘Old and Young’

There is a classic episode of the British television comedy Hancock1 called ‘The Bedsitter’, in which Tony Hancock, in a characteristically vain attempt at self-improvement, decides to ‘have a go’ at Bertrand Russell’s Human Knowledge: Its Limits and Scope.2 Every few sentences – few words even – he has to put the book down and consult the large dictionary on his bedside table (‘Well, if that’s what they mean, why don’t they say so?’). Soon, frustration gets the better of him:

‘No, it’s him. It’s him that’s at fault, he’s a rotten writer. A good writer should be able to put down his thoughts clearly in the simplest terms understandable to everybody. It’s him. He’s a bad writer. Not going to waste my time reading him.’ (Drops Human Knowledge: Its Limits and Scope on the floor and picks up another book.) ‘Ah, that’s more like it – Lady Don’t Fall Backwards.’

Fifty years later, a similar scene was being played out in our house. I lay on the bed with a nice new copy of George Eliot’s Middlemarch, and tried to silence my inner Hancock.

Eliot (from the ‘Prelude’): Who cares much to know the history of man, and how the mysterious mixture behaves under the varying experiments of Time . . .

Hancock (from ‘The Bedsitter’): No, no, I should know. It’s in English, I should know what he’s talking about.3

Eliot: Some have felt that these blundering lives are due to the inconvenient indefiniteness with which the Supreme Power has fashioned the natures of women . . .

Hancock: He’s a human being the same as me, using words, English words, available to us all. Now, concentrate.

I succeeded in reading the ‘Prelude’ in its entirety. (‘Yes, it’s hard graft for we intellectuals these days.’) Then I read it again. It was only three paragraphs long, so I took a quick turn round the room, and then read it a third time. No, it was no good. I could hardly understand a word. But, unlike Hancock, I had no Lady Don’t Fall Backwards to fall back on. Middlemarch and I were going to have to get along.

Of course, the problem was not Middlemarch. Despite my surprise conquest of The Master and Margarita, and the blast of confidence it gave me, I quickly knew I had overreached myself. The Master and Margarita had been an obstacle course; Middlemarch, on the other hand, gave every indication of being a 688-page punishment beating. Once upon a time, I had been in the habit of reading this kind of elaborate, circumlocutory prose. But that was when I was a student, full of piss and vinegar and blithe ignorance. Two decades on, I was gravely out of condition, short of breath, barely limping along. It was too much, too soon, too old.

In those days, as an English literature undergraduate at a self-consciously progressive university, it was possible to read a couple of classics every week – unlikely, almost unheard of, but possible. In contrast, an audit of my current week’s reading would look something like this:

200 emails (approx.)

Discarded copies of Metro

The NME and monthly music magazines

Excel spreadsheets

The review pages of Sunday newspapers

Business proposals

Bills, bank statements, junk mail, etc.

CD liner notes

Crosswords, Sudoku puzzles, etc.

Ready-meal heating guidelines

The occasional postcard

And a lot of piddling about on the Internet

Of these, the Sudoku was the most inexplicable to me. What a waste of time! I loathed it. Yet I could pass a whole train journey wrestling with one small grid, a long hour that brought me little or no pleasure, even on the rare occasions it ended in success. The shelves of the bookstores at Victoria station were packed with competing Oriental number tortures: Sudoku, Sun Doku, Code Doku, Killer Sudoku . . . As a former student acquaintance had written in the concluding sentence of a 10,000-word dissertation on mechanical engineering: ‘It doesn’t matter anyway, because it’s all a load of shit.’4

So, accepting I was in no fit state even to complete an Evening Standard ‘brainteaser’ – Grade: Beginner – why had I felt compelled to attempt Middlemarch, one of the high peaks of the English novel?

As I approached my mid-thirties, before our son was born, while he was still a Nice Idea In The Not Too Distant Future, I started getting the first pangs of a feeling which soon grew acute. The feeling was this: one day soon, I am going to die. Previously, I had enjoyed brooding on my own mortality, because I was young and death was never going to happen to me. Now, however, like many people on the threshold of middle-age, out there in the jungle somewhere I could discern a disconcerting drumbeat; and I realised that at some point in the aforementioned Not Too Distant Future, closer now, the drumming would cease, leaving a terrible silence in its wake. And that would be it for me.

Immediately, we produced a child. But if anything, this only made things worse.

I had heard that other people dealt with this sort of problem by having ill-advised affairs with schoolgirls, or dyeing their hair a ‘fun’ colour, or plunging into a gruelling round of charity marathon running, ‘to put something back’. But I did not want to do any of that; I just wanted to be left alone. My sadness for things undone was smaller and duller, yet maybe more undignified. It seemed to fix itself on minor letdowns, everyday stuff I had been meaning to do but somehow, in half a lifetime, had not got round to. I was still unable to play the guitar. I had never been to New York. I did not know how to drive a car or roast a chicken. Roasting a chicken – the impossible dream! Even my mid-life crisis was a disappointment.

I told myself I had a lot to be thankful for. I had a loving family, lived by the sea in a house which in thirty years I might own, had written a couple of books, knew Paris via its arrondissements, could ride a bike, play the piano and bake a potato on demand. Yet I was not satisfied.

One of the certainties I found myself questioning was my belief in art. For as long as I could remember, from childhood on, I never doubted that ‘great’ books or ‘fantastic’ singles or ‘brilliant’ films were the prerequisites of a balanced and full existence. Their presence in my life as an adolescent and a young adult was constant and their absence unimaginable. If I needed to go without food so I could buy an important record or novel, I went without food – the hungry consumer. But lately I had begun to ask myself whether this loyalty had amounted to anything more than a shed-load of stuff; two shed-loads in fact, one at the bottom of the garden in a bona fide shed and the other in a storage unit up the road.

However meagre my spiritual beliefs, however much I toed the modern secular line, my faith in art had never faltered. Culture could come in many forms, high, low or somewhere in-between: Mozart, The Muppet Show, Ian McEwan.5 Very little of it was truly great and much of it would always be bad, but all of it was necessary to live, to be fully alive, to frame the endless, numbered days and make sense of them.6

Lately, though, I had been feeling like a sucker. As I contemplated the stacks of CDs and VHS tapes, old theatre programmes and superhero comics, wearing a fading t-shirt for some group that had probably split up, they seemed to represent the opposite of the enlightenment they had originally promised. Like me, they were nudging obsolescence. I saw I had got it wrong. I had confused ‘art’ with ‘shopping’.

Books, for instance. I had a lot of those. There they all were, on the shelves and on the floor, piled up by the bed and falling out of boxes. Moby-Dick, Possession, Remembrance of Things Past, the poetry of Emily Dickinson, Psychotic Reactions and Carburettor Dung, a few Pevsners, that Jim Thompson omnibus, The Child in Time, six more Ian McEwan novels or novellas, two volumes of his short stories . . . These books did furnish the room, but they also got in the way. And there were too many I was aware I had not actually read. As Schopenhauer noted a hundred and fifty years ago, ‘It would be a good thing to buy books if one could also buy the time to read them; but one usually confuses the purchase of books with the acquisition of their contents.’7

These books became the focus of a need to do something. They were a reproach – wasted money, squandered time, muddled priorities. I shall make a list, I thought. It will name the books I am most ashamed not to have read – difficult ones, classics, a few outstanding entries in the deceitful Miller library – and then I shall read them. I was thirty-five years old. Ten books maybe, ten books before my fortieth birthday. Yes, ten books in five years; one book every six months; that seemed like an easily achievable goal and vaguely decadent when you held down a full-time job and were still unable to drive to the grocery store to buy a chicken you didn’t know how to cook, because you’d learned to do neither, because you’d been too busy shopping. Excellent! Books first, driving lessons later.

For the next couple of years I did nothing with this plan except congratulate myself on it. I thought about the list a little and talked about it a lot. In the pub, at parties, over lunch, I would sketch out the idea and coquettishly disclose a title or two: The Master and Margarita, Pride and Prejudice, Middlemarch. And each time somebody responded with a disbelieving: ‘You’ve never read The Master and Margarita / Pride and Prejudice / Middlemarch?!’, I would chortle at the effect my words had created, and thus pull a little further away from ever beginning the books in question. Better to speak volumes than to read them.

And so two and a half years passed. Our son arrived. I was halfway to forty and I had read precisely none of the books I could have read in that time, now lost. I hadn’t even drawn up the list. There was no list. It existed only in my head, occasionally summoned into being for an easy laugh, the contents of which could be reshuffled as circumstance or listener demanded. It didn’t matter anyway, because it was all a load of shit.

Then two things happened.

I was talking about the list yet again with an old friend from university, in that manner of ironic bluff and counter-bluff reserved for all men who were students in the 1980s, and in their hearts are students still.

‘Two and a half years gone,’ I said. ‘I’ve only got two and a half years left. I’ll never do it! I’ll never read Middlemarch!’

‘No,’ said my friend. ‘You won’t.’

He meant it. He was neither bluffing, nor calling my bluff. He knew I would not do it, was certain of it, based on his familiarity with my character, his understanding of my family and work commitments, and his appreciation of how tired we all seemed to be these days.

And I knew he was right.

(I should also add that, when we had first discussed this idea, my friend went out and bought Middlemarch, bought and read it and, for the record, enjoyed it. He may possibly have done this because I told him – falsely – that I had already bought, read and enjoyed it myself.)

The second thing that made me stir myself was the aforementioned Sudoku.

Somewhere near Gillingham on a dank November evening, stuck between stations, scratching digits into a box like a tin monkey, after a day at work doing much the same thing in Excel, I experienced an epiphany: Why was I wasting my life like this? Words were my passion, not numbers. And there suddenly rose before me, as if to holler, STOP!, the ghosts of all the printed matter I had consumed in the preceding weeks and months: culture supplements, heritage rock magazines, photocopies and blurbs, Private Eye and the Radio Times, prescriptions and descriptions, print-outs and spreadsheets and Sudoku, Sudoku, killer Sudoku.

Something had to change and I had to change it.

So when Alex and I went to Broadstairs the following day, the appearance of The Master and Margarita there on the shelf of the Albion Bookshop seemed providential. Here was my chance to make good. It was a wild and inspiring and faith-renewing ride and when it was over I wanted to try another one. Plus now I was someone who had read The Master and Margarita. I felt like I had put something back.

Middlemarch, then, was the book I chose to tackle next. But Middlemarch was a much bigger dipper than The Master and Margarita. If that had been a fairground ride, this was like a trip on Space Mountain™ – a formidable test of nerve, and one I wanted to get off way before the end.8

If War and Peace is the most distinguished unread novel in Russian literature, and Remembrance of Things Past its even lengthier French counterpart, then Middlemarch has a modest claim to being the equivalent in English. (‘Middlemarch, twinned with Combray and Bald Hills. Number of visitors: Uncertain.’) It may not be as forbidding as Finnegans Wake or as epic as Clarissa, but it seems to occupy a special status as a book that sorts the heavyweights from the halfwits. For this reason alone, it had always been a fixture of the phantom list; and I suppose it was vaguely reprehensible that a graduate of English Literature should not have read what Virginia Woolf called ‘one of the few English novels written for grown-up people’. I recall as a teenager watching Salman Rushdie on a BBC2 literary panel game – The Book Quiz, was it? – where Rushdie was able to identify some lines from a Bob Dylan song, but not from Middlemarch, which he confessed he had never read – cue much amusement amongst his fellow panel members. Was this, it suddenly occurs to me, where I first picked up the awful habit?9

After a week and a hundred or so hard-won pages, I knew I was in trouble. I found there were plenty of other jobs I suddenly wanted to do – cleaning the oven, a spot of long overdue filing – anything other than pick up this torturous book. There seemed to be a problem. Who were all these various doctors and ladies and landlords and parsons and what on earth were they saying to one another? The whole experience did nothing but compound the sense of my own wretched floccinaucinihilipilification. Not only was I not enjoying Middlemarch, it left me feeling dejected. I was not up to a task others performed with apparent ease. Perhaps I had done little more than swap number puzzles for intellectual fakery – pseudoku. When it came down to it, perhaps I was a halfwit.

Fortunately, at this point Tina staged an intervention. Much as she wished the oven to be clean and the phone bills to be in tidy, chronological order – wished it with all her heart – she also recognised that what I was doing really mattered to me. She had watched as I struggled with The Master and Margarita, and so she reminded me that I needed to let the book do the work. So what if not every line made sense? The drift would do for now.

‘Have you actually read Middlemarch?’ I asked her. ‘There is no drift, there is only confusion. Or as the author would say, in the instance of this poor history, it would not be unfair to envisage a state of superlative driftlessness, and where driftlessness lies about us, there too – alas! – confusion may abide. Etc.’

‘Oh, stop being so melodramatic,’ she said. ‘Just do what I did. Read fifty pages a day and leave it at that.’

Do you perceive my wife’s brilliance? Is it plain to you, simple reader? It lay not in the essential nobility of her heart, or that she herself already stood atop Middlemarch and was gently beckoning her husband to join her. No. It was that she had a system. Fifty pages every day. It wasn’t exciting, in itself it did not elevate the spirit, but it worked. It allowed time for books and time for life to go on. It was the key both to all mythologies and a clean oven.

And so I accepted that the first few days of Middlemarch would be a chore. I started over, counting down each fifty-page segment like it was my homework. Gradually, however, the mists dissolved and the sun began to shine on a fictional corner of the West Midlands. The model for Middlemarch had been Coventry, so in the short term, some amusement was had from reading the highfalutin dialogue aloud with a regional twang (‘I am fastidious in voices, and I cannot endure listening to an imperfect reader’) and speculating how close Middlemarch lay to Ambridge. Just as with The Master and Margarita though, there was something seductive about Middlemarch and I started to succumb; but whereas Bulgakov’s technique is conjuring and grand gestures, Eliot works an intellectual seduction, a slow game of pace and frustration. Sentences picked up as I became accustomed to the rhythms of the prose. The per diem fifty pages increased; I stopped mucking about with the voices. I shan’t pretend that I understood all the subtleties of issues pertaining to the Reform Bill of June 1832, around which the novel thematically revolves, but the layering of character and motive – and the moral issues the characters have to confront – seemed thrillingly ambitious and sophisticated. When the novel’s perspective switches from Dorothea to Casaubon at the start of Chapter 29 – ‘but why always Dorothea? Was her point of view the only possible one with regard to this marriage?’ – there follows a passage so sublime and wise and complex that the only word to describe it is: genius.

(A spoiler follows. As in the sport of football, look away now if you don’t want to know what happens.)

By the time Casaubon dies in the summerhouse, resentful and alone, I was besotted with the book. I could not believe how much I was enjoying it.

On a seven-hour journey back from Edinburgh, I hardly lifted my head from my book, welcomed an enforced delay in the airport departure lounge, was grateful to miss a connection at Heathrow, sat in the bone-freezing cold at the station for half an hour in order to discover the ending for Dorothea Brooke and Will Ladislaw, before walking home, elated. I mean exactly that; I was elated. I felt the unmistakable certainty that I had been in the presence of great art, and that my heart had opened in reply.

Plus, now I was someone who had read Middlemarch and The Master and Margarita. Two down.

We live in an era where opinion is currency. The pressure is on us to say ‘I like this’ or ‘I don’t like that’, to make snap decisions and stick them on our credit cards. But when faced with something we cannot comprehend at once, which was never intended to be snapped up or whizzed through, perhaps ‘I don’t like it’ is an inadequate response. Don’t like Middlemarch? It doesn’t matter. It was here before we arrived, and it will be here long after we have gone. Instead, perhaps we should have the humility to say: I didn’t get it. I need to try harder.

I learned to love Middlemarch. I had also been reminded of the value of perseverance. I determined to finish what I had started. So the following weekend, we finalised the selection. I wrote down the names of the books on a piece of paper and Tina witnessed and signed it. We christened it ‘The List of Betterment’. And afterwards we sat down to a special Sunday lunch which Dad had prepared for the whole family.

Baked potatoes.10

Postscript

This was not quite the end of Middlemarch. Of the novels I read during this period, Middlemarch is one that stayed with me over several years – haunted me, I should say. As one deadline after another expired, and still I came no closer to completing work on this book, I would remember poor old Casaubon and his unfinished Key to all Mythologies: ‘the difficulty of making his Key to all Mythologies unimpeachable weighed like lead upon his mind . . .’ And I would also recall Dorothea’s forlorn plea to her husband: ‘All those rows of volumes – will you not now do what you used to speak of? – will you not make up your mind what part of them you will use, and begin to write . . .’

And so I give thanks that, if you are reading these words, I have been at least partially successful and not conked out at my desk before I could finish what I started; and I also give thanks that we, unlike the Casaubons, are still married.

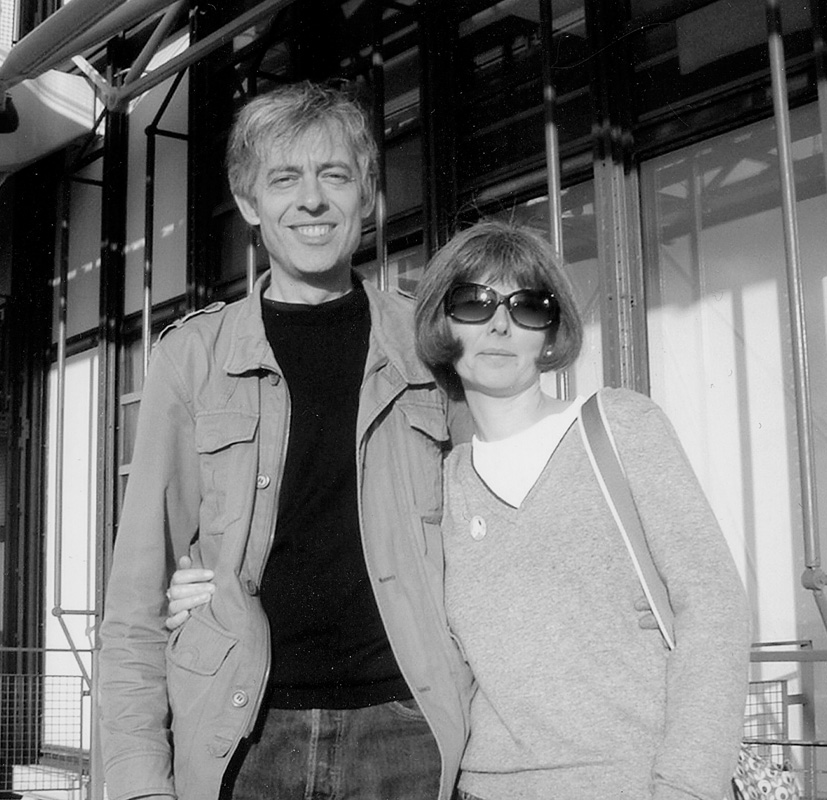

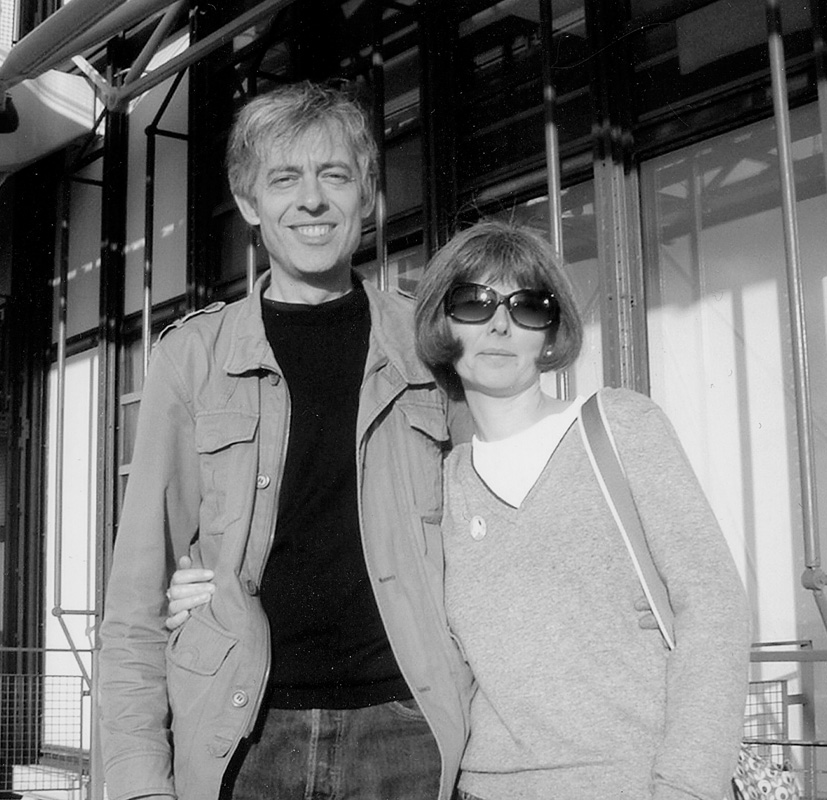

Fig. 4: Propped up by a saint.

(photograph by Alex Miller)