Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

‘As a hungry animal seizes every object it meets, hoping to find food in it, so Vronsky unconsciously seized now on politics, now on new books, now on pictures.’

Anna Karenina, Part V, Chapter 8

‘“You have a consistent character yourself and you wish all the facts of life to be consistent, but they never are . . . You also want the activity of each separate man to have an aim, and love and family life always to coincide – and that doesn’t happen either. All the variety, charm and beauty of life are made up of light and shade.”’

Anna Karenina, Part I, Chapter 11

At the National Gallery in London, Alex and I were standing at the feet of a tiger in a typhoon.

‘Grrr!’ said Alex, pointing up at the painting and giggling. ‘Grrr!’

I tried to smile at the blazer-wearing attendant who was sitting next to the picture but she refused to look at us. My happy child threatened to disrupt the sombre mood of her gallery. What do I think this is, Tate Modern?

Fig. 7: Surpris! (Surprised!). Henri Rousseau, 1891. Tiger, bottom left.

(copyright © 2014 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC)

‘You’re right, Alex,’ I told him. ‘Grrr!’

It was the week after Christmas. The National Gallery was full of families, parties of tourists and shoppers taking a break from the sales. They congregated near the Water-Lilies or Sunflowers, before making a beeline for the Sainsbury’s gift shop – sorry, the Sainsbury Wing gift shop – to purchase headscarves or jigsaws or, bizarrely, miniature ginger-haired, one-eared Vincent Van Gogh dolls you could stick to the door of your fridge.

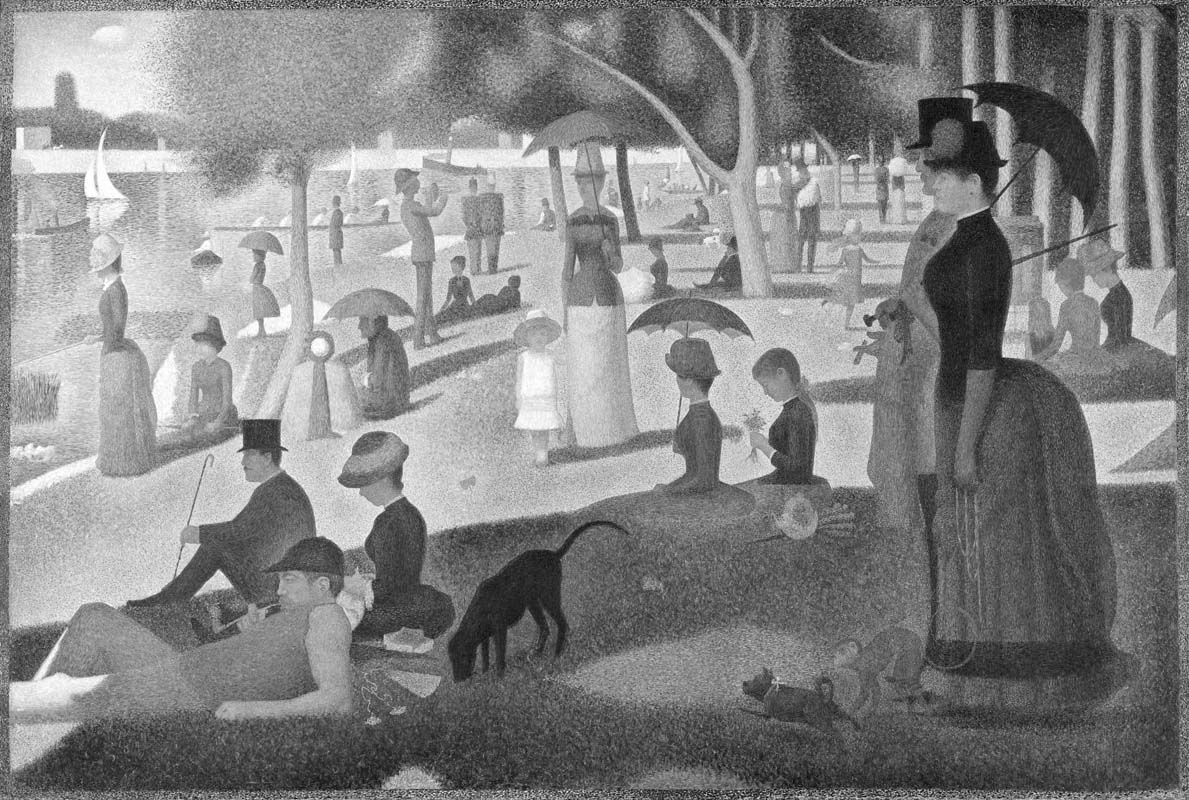

Twenty yards away, through a set of heavy wooden double doors, on the south wall of the Harry and Carol Djanogly Room, at a height of approximately 440 centimetres off the ground (I feel the spirit of Dan Brown working through me) was a painting I wanted Alex to see. Georges Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières is my favourite picture in the National Gallery. If I am passing, and I have time to spare, I will come to Room 44 and sit in front of it and rest like the boy in the straw hat. It measures 201 by 300 centimetres, which is irrelevant. Look at the picture, the haze of a summer’s day by the Seine more than a century ago. Asnières was an industrial suburb of Paris; in the background Seurat has painted the smoking chimneys of the local factories. Should these youths be at work? Or is light industry intruding on their day off, contributing smog to a lazy blue sky? At these moments, such questions are irrelevant too. The painting is a pool of colour and light.

‘What do you think?’ I asked Alex.

‘I like the doggy,’ said Alex thoughtfully. ‘Woof!’

Fig. 8: Une Baignade, Asnières (Bathers at Asnières). Georges Seurat, 1884. Dog, bottom left.

(courtesy National Gallery)

He was right again. The dog completes the painting; its tail, its alertness, its solidity. Everything else in the picture is infectiously drowsy and slow.

Seurat’s elevation of such a humdrum scene and determinedly common people was considered rather ludicrous in its day. It always puts me in mind of Jacques Demy’s 1964 film Les parapluies de Cherbourg, which takes the commonplace setting of a dingy Normandy fishing port and stages a winsomely pretty social-realist musical in it – an idea which, if you don’t get it, must seem ludicrous too. But Seurat’s painting and Demy’s film, like William Eggleston’s photographs or Ray Davies’ songs for The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society, frame ‘ordinary’ people in provincial situations and make them glow. Their gaze is not uncritical but it rarely patronises. I would like to call it magical realism but that term is already taken, having been registered at a sweltering Latin-American patent office in the early 1980s and usually signifying a mixture of the real and the surreal (‘surreal realism’ never caught on). Let’s just say I like the doggy too, because Seurat has painted a real dog magically, not a fantastical dog with wings and a top hat.

In the gift shop, Alex and I bought postcards, a small hardback of Rousseau’s animal pictures and a Monet phoneblock for my mother. We left the magnetic Vincents where they were. Alex was old enough now to enjoy going to museums, galleries and cinemas, and their gift shops too. They were all parts of the same experience, and we liked visiting them together, together.

Outside, preparations were being made for the imminent New Year celebrations, when crowds of revellers would gather in Trafalgar Square and revel through the night. (Just as the word ‘flotilla’ has become tied to the phrase ‘little ships’, so ‘reveller’ only seems to come out on New Year’s Eve.) I would not be doing much revelling myself this year but I would be having a marvellous time. I would be reading Tolstoy.

A few weeks earlier at a Christmas drinks party, I had met a gentleman from Louisiana who had gone into raptures over A Confederacy of Dunces, not because of its ferociously cynical worldview but because it offered a realistic social portrait of his hometown, New Orleans. I explained about the List of Betterment.

‘Oh my God!’ he cried. ‘Have you read Anna Karenina? Tell me you’re going to read Anna Karenina!’

Yes, I said. I am going to read Anna Karenina. It still felt audacious to say this and know it was true.

On Christmas Eve, I began Aннa Kapeнинa (Anna Karenina, though Karenin is arguably more correct). On Christmas Day, between unwrapping presents, assembling a Noah’s Ark and basting my first turkey, I read some more. By Boxing Day my priority was no longer my own family but the Oblonskys and their circle. At my mother-in-law’s I stole away to the spare bedroom when the Pictionary came out. This was not just a great book; it was a great book I could love. Of course, I loved my family too, never more so than when in another part of the house, reading about someone else’s family, long ago and far away.

Is it wrong to prefer books to people? Not at Christmas. A book is like a guest you have invited into your home, except you don’t have to play Pictionary with it or supply it with biscuits and stollen. Tina and I were still getting used to the shape of Christmas now Alex was part of the family. When he was a baby, we had been appalled to discover that he would not even give us Christmas Day off. He was worse than Scrooge! No more lying around in bed, sipping sherry and blubbing at the heartwarming seasonal specials on TV. Now Alex was a few years older, Christmas was an enchanted time, not least for the grandparents who, having spent many years slaving over sprouts, spuds and turkeys for their own broods, could now sit back and watch us do the same for them. This is what is called ‘the circle of life’.

When Alex was born, my aunt gave me a far-sighted piece of advice. ‘Family life is wonderful, Andrew,’ she told me, ‘but you have to give in to it.’ I think my aunt knew I might find this a challenge – and she was right. Having a child brought with it a new, unanticipated role I did not really want. I loved being Alex’s dad but I could do without the secondary responsibilities to everybody else. It was hard, repetitive and often nerve-jangling work. Tina’s mum and dad are long divorced; my mother lives on her own; my brother-in-law and his family emigrated to Australia a few years ago. So at Christmas, we don’t just have to chop and shop and wrap and cook, we do it atop an emotional powder keg which might blow at any time between the first long-distance Skype call and the Queen’s Speech.

‘All happy families resemble one another, but each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way’ reads the famous opening statement of Anna Karenina. Did Tolstoy give in to family life? Despite being married for nearly fifty years and having thirteen (legitimate) children, he did not. Instead, the great man bent family life to fit round him, thus ensuring that his family was not unhappy in its own way but in his. It was a domestic arrangement that was ‘one of the most miserable in literary history’, according to one biographer.

Of course, for a while it resulted in great work. But the work proved not to be enough for the great man making it. With hindsight, the novel is testimony to its author’s growing disenchantment not just with families but with art itself. ‘The two drops of honey which diverted my eyes from the cruel truth longer than the rest: my love of family, and of writing – art as I called it – were no longer sweet to me,’ he recalled a few years later in the memoir A Confession. Shortly after Anna Karenina was published, Tolstoy publicly repented of his wasteful life to date, his youthful ambition, the compulsive womanising and novelising. War and Peace had been a mistake, so had Anna. Fiction itself was as sinful as lust unless directed to a higher purpose. Henceforth, he would turn away from anything that did not glorify Jesus’ teachings – or Tolstoy’s interpretation of them – and prepare His kingdom on Earth. It was one of the most masochistic mid-life crises imaginable, but Tolstoy being Tolstoy, there was no turning back. For the next three decades he attempted to live as a Christian anarchist, a peasant, a holy man – anything but a writer of fiction or a father, though he could not quite suppress either impulse. The Countess Tolstoy had good reason to complain, which she did, incessantly.

I don’t know what Christmas was like in the Tolstoy residence but there was probably some tension between celebrating the birth of Jesus and celebrating the life of Tolstoy. Abandoning art does not seem to have brought much peace to his titanic ego. He knew that his essays and his sermons, though pure in conception and execution, carried only a fraction of the authority of his damnable fiction – his transcendent later stories like The Death of Ivan Ilyich and The Kreutzer Sonata merely confirmed this. Nabokov relates the story of Tolstoy ‘picking up a book one dreary day in his old age, many years after he had stopped writing novels, and starting to read in the middle, and getting interested and very much pleased, and then looking at the title – and seeing: Anna Karenin by Leo Tolstoy’.

By now, I had been reading the List for nearly two months. Every book had had something extraordinary about it. Yet Anna Karenina was so grand, so all-encompassing, that it seemed to contain all those remarkable books within it. It was as elaborate as Middlemarch, as idiosyncratic as The Sea, The Sea and, every so often, as brutal as Post Office. Its climax was as moving as Twenty Thousand Streets . . . and as experimental as The Unnamable. It offered a working overview of nineteenth-century agricultural theory which was Melvillian in scope. It even had several characters standing around in wheat fields, leaning on ploughshares and arguing about communism. It had it all.

In other words, Anna Karenina made good on the promise I had divined in The Master and Margarita. This was the book, or the gap, I had been hunting from the beginning, from before the beginning. It was the perfect balance of art and entertainment – no, not a balance, a union of the two. One was indivisible from the other. The way in which Tolstoy framed his characters’ choices was startlingly contemporary, their psychological dilemma, their suffering and moments of clarity; or maybe it was timeless and therefore always contemporary. Like people, they contradicted themselves. They changed their beliefs, their temper, their appearance. In a lesser writer this might seem like inconsistency but in Tolstoy’s hands this changeability was completely lifelike. The scale of the plot and the Russianness of the names soon seemed inconsequential. And when he chose to create a set piece, such as the birth of a child or the lingering death of an invalid, one felt he was aiming to articulate the last word on the subject, so pristine was the detail and so forceful the character behind it. It could not be described as an easy read, and perhaps if I had not just finished Eliot and Melville and Beckett and Toole and Tressell, one after another, I would not have found Anna Karenina so beguiling or so straightforward. But I was not intimidated by the book. Like Seurat’s painting or Les parapluies de Cherbourg or my beloved Kinks records, Anna Karenina was like the real world, only better.

Of course, to a small child on Christmas morning, the real world is like the real world, only better. First Father Christmas and his reindeer, then Mummy and Daddy, and Granny and Granddad and Nanny – no, darling, Granddad doesn’t live with Granny; no, he doesn’t live with Nanny either – showering you with love and, more importantly, piles and piles of parcels containing toys and sweeties and books. It is a day of magical realism. And in a break from peeling vegetables and averting fights, my son and I sat and flicked the pages of a picture book, basking in it all together.

Early that morning, Alex had presented me with a shiny gold envelope containing my Christmas gift. Inside was a pair of tickets for a show called Sunday in the Park with George, a Sondheim musical I had never seen, which was at the time being revived in the West End of London. As its starting point, it took the paintings of Georges Seurat, in particular the pointillist masterpiece which followed Bathers at Asnières – the view from across the river, Un dimanche après-midi à l’Île de la Grande Jatte or A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of la Grande Jatte. It was the perfect present.

The attentive reader will have noticed that I love musicals. This, along with a deep-seated dislike of sport, barbecues and cars, is what has led my wife to refer to me as a flamboyant heterosexual. To some, the modern stage musical is hopelessly unserious, inherently camp or detestably bourgeois, like the novel or the family: ‘Thatcherism in action’ according to one respected critic. Certain shows struggle to defy the gravity of their source material – I refer you to the scathing reviews that greeted Moby! A Whale of a Tale and numbers such as ‘Mr Starbuck’ and ‘In Old Nantucket’. But my parents adored Lerner and Loewe, Rodgers and Hammerstein, Frank Loesser et al., and as a child obsessed by pop music and storytelling, I loved how their songs compressed wordplay and emotion and plot into three-minute tunes. Now I am a grown-up, I still do. This is not to say all musicals are good – when they are bad, they are disastrous – but I like the populism of these shows and their vividness and the fact that, when they work, they create more than the sum of many different disciplines and talents. I also love singing. Jacques Demy, speaking of his own musicals, once said singing was ‘a way of communicating that I find more interesting. It can be more tender, more generous, more violent, more aggressive, more gentle, whatever.’

(Another coincidence: while watching the documentary L’univers de Jacques Demy again this morning to make a note of the above quote, I was amazed to see that in the mid-1970s Demy and his Parapluies . . . collaborator Michel Legrand planned a film musical adaptation of Anna Karenina called Anouchka. Demy, his wife Agnès Varda and their two children even moved to Moscow and started learning Russian. Demy and Legrand got as far as finishing the score before funding for the picture fell through.)

My Sunday in the Park with George tickets were for the end of the month, which meant I would have time to take Alex to see Seurat’s painting in London, and show him why Dad was so pleased with his present. And by that time, I might even have ticked off the few remaining books on the List. After Anna Karenina, if I stuck to my original target, there were only two to go. Not that I was in any rush to finish it quickly. Anna Karenina really was better than Christmas.

I shall not attempt to précis the plot of Anna Karenina. The story is long, convoluted and utterly enthralling, and if you have not done so already, my every effort in these few pages is directed towards getting you to read it. But here is a summary of its central theme, taken from Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events: ‘A rural life of moral simplicity, despite its monotony, is the preferable personal narrative to a daring life of impulsive passion, which only leads to tragedy.’ (Book the Tenth: The Slippery Slope)

In the middle of the novel, there is an interlude of sorts. Anna has abandoned her husband and young son Seryozha – her duty – and is touring Europe with her lover, Count Alexei Vronsky. Tolstoy tells us they have passed through Venice, Rome and Naples and are now arrived in ‘a small Italian town where they meant to make a longer stay’. Their self-imposed exile from St Petersburg society is placing the relationship under some strain. Vronsky, an army officer, in particular is growing restless. For a while, he takes up painting. The couple make the acquaintance of a notable Russian émigré artist, Mikhaylov, whom Vronsky commissions to paint Anna’s portrait. He cannot grasp why Mikhaylov’s sketches of Anna capture her essence, ‘that sweet spiritual expression’, so much better than his own efforts. Nor can he and Anna understand why Mikhaylov does not wish to cultivate their acquaintance as they wish to cultivate his: ‘His [Mikhaylov’s] reserved, disagreeable, and apparently hostile attitude when they came to know him better much displeased them, and they were glad when the sittings were over, the beautiful portrait was theirs, and his visits ceased.’1

Mikhaylov is a distant, more productive relation of Ignatius J. Reilly. We are introduced to him in his studio, working at his ‘big picture’, a giant canvas of ‘Pilate’s Admonition – Matthew, chapter xxvii’. He has just argued with his wife because she has failed to pacify their landlady, who is clamouring for the rent. ‘He never worked with such ardour or so successfully as when things were going badly with him, and especially after a quarrel with his wife. “Oh dear! If only I could escape somewhere!” he thought as he worked.’ The painting may never be finished; Mikhaylov erases, reworks and chases inspiration as and when it comes to him. A stray grease spot fills him with joy because it suggests a new pose: ‘Remembering the energetic pose and prominent chin of a shopman from whom he had bought cigars, he gave the figure that man’s face and chin.’ In this setting, Anna and Vronsky are ill-educated and intrusive. Mikhaylov craves their opinion and their trade; having secured both, he cannot wait to be rid of them, especially Vronsky’s dilettante trifling with art, which pains him dreadfully: ‘One cannot forbid a man’s making a big wax doll and kissing it. But if the man came and sat down with his doll in front of a lover, and began to caress it as the lover caresses his beloved, it would displease the lover. It was this kind of unpleasantness that Mikhaylov experienced when he saw Vronsky’s pictures: he was amused, vexed, sorry, and hurt.’

Shortly after the portrait is completed, Anna and Vronsky return to St Petersburg, and neither they nor we meet Mikhaylov again. But in four short chapters, Tolstoy sums up the never-ending transaction between the eternal values of art and the muddled world of the artist. Plus he makes you laugh. I had just finished this Mikhaylov interlude when I took Alex to look at Bathers at Asnières at the National. Seurat’s picture had long since escaped the shackles of Seurat’s life but it still bore the imprint of his character. Although his technique of painting in thousands of tiny dots had been given a technical name – ‘divisionism’ or ‘pointillism’ – it remained the product of an individual’s vision. And like Mikhaylov reluctantly courting Anna and Vronsky, an artist’s posthumous reputation was still subject to the ebb and flow of public opinion and the readiness of galleries and institutions to popularise the image of his painting, and thus their own reputations, via mouse mats or jigsaws, ginger fridge magnets or big wax dolls. The picture was finished years ago but the rent is always due.

The same nagging tension lies at the heart of Sunday in the Park with George (which, it hardly needs saying, is a bit more complicated than Jersey Boys). As Seurat works on Un dimanche après-midi à l’Île de la Grande Jatte, we are first shown the personal sacrifices that go into its creation and then, in the second act, the tricky negotiations with popularity that continue into the present day – the business of art. From my seat in the stalls, not five minutes from the Bathers, I watched as both painting and sacrifice were brought miraculously to life.

Fig. 9: Un dimanche après-midi à l’Île de la Grande Jatte (A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte). Georges Seurat, 1886.

Never mind the dogs, here’s a monkey, bottom right.

(courtesy Art Institute of Chicago)

Sondheim and playwright James Lapine build the show around Seurat’s real writings on pointillist theories of colour and light – design, tension, composition, balance, harmony – and apply them first to the imagined lives of the characters in the painting, then Seurat and his mistress Dot (their invention), then the modern art scene and the efforts of Seurat’s great-grandson George to find inspiration and funding for his own artworks. Much of this is sung to a score whose staccato notes suggest the dots of paint from Seurat’s paintbrush. The songs jump between the real world and the painting, and characters come and go from both. At one point, Seurat gives voice to the dogs in the park, which rise or fall from the stage at his command.2 ‘Finishing the Hat’, ‘Color and Light’, ‘Move On’, ‘Putting it Together’: the metaphor should buckle under the strain but it never does. The refrain of the latter – art isn’t easy – repeated by the younger George as he schmoozes a gallery of wealthy potential patrons, could be the theme tune of the last few months. I have rarely, if ever, been so moved in a theatre. For much of the second half, I felt like something enormous was trying to escape from my chest.

In Act II, Seurat’s daughter, now in her nineties and confined to a wheelchair, reports one of her mother’s favourite sayings. ‘You know, there are only two worthwhile things to leave behind when you depart this world of ours – children and art.’ She then sings wistfully and delicately of ‘. . . La Grande Jatte’, painted by her father long ago, as ‘our family tree’. Great art is our family tree, just as children are a glimpse into the future and the past. Tolstoy came to view these essential elements of life, children and art as barriers to enlightenment, but surely he was wrong? When we find a painting or a novel or a musical we love, we are briefly connected to the best that human beings are capable of, in ourselves and others, and we are reminded that our path through the world must intersect with others. Whether we like it or not, we are not alone. Tolstoy realised this in Anna Karenina but after his conversion he spent much of his subsequent life trying to deny it or postpone it to the afterlife. Families and art, paintings and crowds, books and their troublesome readers: composition, balance, tension, harmony. It is our duty and our privilege to try to resolve these things here and now, with the help of a song or a decent book. Because they will not wait for later.

When we got home, I looked in at Alex, asleep. I was somebody’s son and somebody’s father. It had not been much consolation for Tolstoy but I was not Tolstoy.

I could do better.