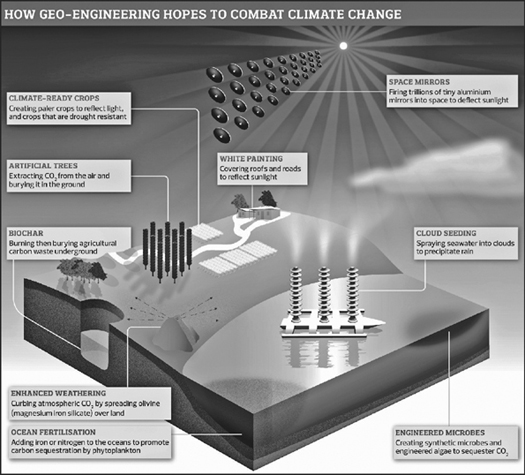

This diagram illustrates how a number of geoengineering projects could be used to transform the Earth’s climate by drawing carbon out of the atmosphere and reflecting sunlight back into space. (illustration credit ill.17)

THE LONG-TERM GOAL for Homo sapiens as a species right now should be to survive for at least another million years. It’s not much to ask. As we know, a few species have survived for billions of years, and many have survived for tens of millions. Our ancient ancestors started exploring the world beyond Africa over a million years ago, and so it seems fitting to pick the next million years as the first distant horizon where we’ll set our sights. We’ve already talked about how we can start this journey by building cities that are safer and more sustainable. Eventually, however, we’re going to build cities on the Moon and other planets. Our future is among the stars, as the science-fiction author Octavia Butler suggests. But long before we have the technologies to get there, our survival will depend on looking at Earth from the perspective of extraterrestrials.

Imagine we’re on an interstellar voyage and we encounter an Earthlike planet. As we survey it from orbit, we discover that this planet is full of life, and covered with sprawling artificial structures built by a scientifically advanced civilization. Seeing those, most of us would say the planet is controlled by a group of intelligent beings. That’s the extraterrestrial perspective. Right now, we’re stuck in the terrestrial perspective, where we do not really regard ourselves as “controlling” the Earth. Nor do we see ourselves as one group. From space we might look like a unified civilization of clever monkeys who hang out together building towers, but down on Earth we are Russians, Nigerians, Brazilians, and many other identities that divide us. Our differences aren’t always a problem. But they have so far prevented us from coming up with a global solution to maintaining the Earth’s resources. We won’t make it into the far future unless we start banding together as a species to control the Earth in a way we never have before.

When I say “control the Earth,” I don’t mean that we’ll all shake our fists at the sky and declare ourselves masters of everything. As entertaining as that would be, I’m talking about something a bit less grandiose. We simply need to take responsibility for something that’s been true for centuries: Human beings control what happens to most ecosystems on the planet. We’re an invasive species, and we’ve turned wild prairies into farms, deserts into cities, and oceans into shipping lanes studded with oil wells. There is also overwhelming evidence that our habit of burning fossil fuels has changed the molecular composition of the air we breathe, pushing us in the direction of a greenhouse planet. More than at any other time in history, humans control the environment. Still, our environment is going to change disastrously at some point, whether it’s heated by our carbon emissions from fossil fuels or cooled by megavolcano eruptions.

Our first priority in the near future must be to control our carbon output. I cannot emphasize this enough. As environmental writers like Bill McKibben and Mark Hertsgaard have argued, our fossil-fuel emissions are heating up the planet, and we can prevent this situation from becoming worse by using green sources of energy. Maggie Koerth-Baker points out in Before the Lights Go Out: Conquering the Energy Crisis Before It Conquers Us that we already have several types of sustainable energy to choose from, including solar and wind. Government representatives who attend the annual U.N. Climate Change Conferences are also coming up with strategies to encourage countries to curb fossil-fuel use, proposing everything from carbon taxes to emissions regulations.

The problem is that our climate has already been permanently changed for the next millennium, as the geobiologist Roger Summons explained in part one of this book. To prevent the planet from becoming uninhabitable, we’ll have to take our control of the environment a step further and become geoengineers, or people who use technology to shape geological processes. Though “geoengineering” is the proper term here, I used the word “terraforming” in the title of this chapter because it refers to making other planets more comfortable for humans. Earth has been many planets over its history. As geoengineers, we aren’t going to “heal” the Earth, or return it to a prehuman “state of nature.” That would mean submitting ourselves to the vicissitudes of the planet’s carbon cycles, which have already caused several mass extinctions. What we need to do is actually quite unnatural: we must prevent the Earth from going through its periodic transformation into a greenhouse that is inhospitable to humans and the food webs where we evolved. Put another way, we need to adapt the planet to suit humanity.

Over the coming centuries, we’ll need to take measures more drastic than cutting back on fossil-fuel use and ramping up the deployment of alternative energies. Eventually we’ll have to “hack the planet,” as they say in science-fiction movies. And we’ll do that in part by re-creating great planetary disasters from history.

To make Earth more human-friendly, our geoengineering projects will need to cool the planet down and remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. These projects fall into two categories. The first, called solar management, would reduce the sunlight that warms the planet. The second, called carbon-dioxide removal, does exactly what it sounds like. Futurist Jamais Cascio, author of Hacking the Earth: Understanding the Consequences of Geoengineering, predicts that we’ll see an attempt to initiate a major geoengineering project in the next 10 years, and it will probably be solar management. “It’s a faster effect and tends to be relatively cheap, and some estimates are in the billion-dollar range,” he said. “It’s cheap enough that a small country or a rich guy with a hero complex who wants to save the world could do it.” Indeed, one solar-management project is already under way, albeit inadvertently. Evidence suggests that sulfur-laced aerosol exhaust emitted by cargo ships on the ocean changes the structure of high clouds, making them more reflective and possibly cooling temperatures over the water. Some solar-management plans take note of this discovery, and propose that we fill the oceans with ships spraying aerosols high into the air. But other strategies are more radical.

To find out how we’d shield our planet from sunlight, I visited the University of Oxford, winding my way through the city’s maze of pale gold spires and stone alleys to find an enclave of would-be geoengineers. Few deliberate geoengineering projects have been tried to date, but the mandate of the future-focused Oxford Martin School is to tackle scientific problems that will become important over the next century. The center is helping invent a field of science that doesn’t properly exist yet—but that will soon become critically important. One of its researchers is Simon Driscoll, a young geophysicist who divides his time between studying historic volcanic eruptions and figuring out how geoengineers could duplicate the effects of a volcano in the Earth’s atmosphere without actually blowing anything up.

Driscoll told me what volcanoes do to the atmosphere while cobbling together cups of tea in the cluttered atmospheric-physics department kitchen. Along with all the flaming lava, they emit tiny airborne particles called aerosols, which are trapped by the Earth’s atmosphere. He cupped his hands into a half sphere over the steam erupting from our mugs of tea, pantomiming the layers of Earth’s atmosphere trapping aerosols. Soot, sulfuric acid mixed with water, and other particles erupt from the volcano, shoot far above the breathable part of our atmosphere but remain hanging somewhere above the clouds, scattering solar radiation back into space. With less sunlight hitting the Earth’s surface, the climate cools. This is exactly what happened after the famous eruption of Krakatoa in the late 19th century. The eruption was so enormous that it sent sulfur-laced particles high into the stratosphere, a layer of atmosphere that sits between ten and forty-eight kilometers above the planet, where they reflected enough sunlight to lower global temperatures by 2.2 degrees Fahrenheit on average. The particles altered weather patterns for several years.

Driscoll drew a model of the upper atmosphere on a whiteboard. “Here’s the troposphere,” he said, drawing an arc. Above that he drew another arc for the tropopause, which sits between the troposphere and the next arc, the stratosphere. Most planes fly roughly in the upper troposphere, occasionally entering the stratosphere. To cool the planet, Driscoll explained, we’d want to inject reflective particles into the stratosphere, because it’s too high for rain to wash them out. These particles might remain floating in the stratosphere for up to two years, reflecting the light and preventing the sun from heating up the lower levels of the atmosphere, where we live. Driscoll’s passion is in creating computer models of how the climate has responded to past eruptions. He then uses those models to predict the outcomes of geoengineering projects.

The Harvard physicist and public-policy professor David Keith has suggested that we could engineer particles into tiny, thin discs with “self-levitating” properties that could help them remain in the stratosphere for over twenty years. “There’s a lot of talk about ‘particle X,’ or the optimal particle,” Driscoll said. “You want something that scatters light without absorbing it.” He added that some scientists have suggested using soot, a common volcanic by-product, because it could be self-levitating. The problem is that data from previous volcanic eruptions shows that soot absorbs low-wavelength light, which causes unexpected atmospheric effects. If past eruptions like Krakatoa are any indication—and they should be—massive soot injections would cool most of the planet, but changes in stratospheric winds would mean that the area over Eurasia’s valuable farmlands would get hotter. So the unintended consequences could actually make food security much worse.

It’s not clear how we’d accomplish the monumental task of injecting the particles, but Driscoll’s colleagues at Oxford believe we could release them from spigots attached to enormous weather balloons. Weather balloons typically fly in the stratosphere, and they could release reflective particles as a kind of cloud while remaining tethered to an ocean vessel. The stratosphere’s intense winds would carry the particles all around the globe. However, getting particles into the atmosphere isn’t the tough part.

The real issues, for Driscoll and his colleagues, are the unintended consequences of doping our atmosphere with substances normally unleashed during horrific catastrophes. Rutgers atmospheric scientist Alan Robock has run a number of computer simulations of the sulfate-particle injection process, and warns that it could destroy familiar weather patterns, erode the ozone layer, and hasten the process of ocean acidification, a major cause of extinctions.

“I think a lot about the doomsday things that might happen,” Driscoll said. Unintended warming and acidification are two possibilities, but geoengineering could also “shut down monsoons,” he speculated. There are limits to what we can predict, however. We’ve never done anything like this before.

If the planet starts heating up rapidly, and droughts are causing mass death, it’s very possible that we’ll become desperate enough to try solar management. The planet would rapidly cool a few degrees, and give crops a chance to thrive again. What will it be like to live through a geoengineering project like that? “People say we’ll have white skies—blue skies will be a thing of the past,” Cascio said. Plus, solar management is only “a tourniquet,” he warned. The greater injury would still need treating. We might cut the heat, but we’d still be coping with elevated levels of carbon in our atmosphere, interacting with sunlight to raise temperatures. When the reflective particles precipitated out of the stratosphere the planet would once again undergo rapid, intense heating. “You could make things significantly worse if you’re not pulling carbon down at the same time,” Cascio said. That’s why we need a way of removing carbon from the atmosphere while we’re blocking the sun.

One of the only geoengineering efforts ever tried was aimed at pulling carbon out of the atmosphere using one of the Earth’s most adaptable organisms: algae called diatoms. Researchers have suggested that we could scrub the atmosphere by re-creating the conditions that created our oxygen-rich atmosphere in the first place. In several experiments, geoengineers fertilized patches of the Southern Sea with powdered iron, creating a feast for local algae. This resulted in enormous algae blooms. The scientists’ hope was that the single-celled organisms could pull carbon out of the air as part of their natural life cycle, sequestering the unwanted molecules in their bodies and releasing oxygen in its place. As the algae died, they would fall to the ocean bottom, taking the carbon with them. During many of the experiments, however, the diatoms released carbon back into the atmosphere when they died instead of transporting it into the deep ocean. Still, a few experiments suggested that carbon-saturated algae can sink to the ocean floor under the right conditions. More recently, an entrepreneur conducted a rogue geoengineering project of this type off the coast of Canada. The diatoms bloomed, but the jury is still out on whether ocean fertilization is a viable option.

So it’s possible that algae will be helping us in our geoengineering projects. Another possibility is that we’ll be enlisting the aid of rocks. One of the most intriguing theories about how we’d manipulate the Earth into pulling down carbon was dreamed up by Tim Kruger, who heads the Oxford Martin School’s geoengineering efforts. I met with him across campus from Driscoll’s office, in an enormous stone building once called the Indian Institute and devoted to training British civil servants for jobs in India. It was erected at the height of British imperialism, long before anyone imagined that burning coal might change the planet as profoundly as colonialism did.

Kruger is a slight, blond man who leans forward earnestly when he talks. “I’ve looked at heating limestone to generate lime that you could add to seawater,” he explained in the same tone another person might use to describe a new recipe for cake. Of course, Kruger’s cake is very dangerous—though it might just save the world. “When you add lime to seawater, it absorbs almost twice as much carbon dioxide as before,” he continued. Once all that extra carbon was locked into the ocean, it would slowly cycle into the deep ocean, where it would remain safely sequestered. An additional benefit of Kruger’s plan is that adding lime to the ocean could also counteract the ocean acidification we’re seeing today. Given that geologists have ample evidence that previous mass extinctions were associated with ocean acidification, geoengineering an ocean with lower acid levels is obviously beneficial. “A caveat is that we don’t know what the environmental side effects of this would be,” Kruger said, echoing the refrain I’d already heard from Driscoll and others.

Kruger’s idea depends on something that the algae plan does as well. It’s called ocean subduction, and it refers to the slow movement of chemicals between the upper and lower layers of the ocean. Near the ocean surface, oxygen and atmospheric particles are constantly mixing with the water. When this layer becomes saturated with carbon, we see carbon levels rise in the atmosphere because the ocean can no longer act as a carbon sink. But the lower reaches of the ocean can sequester massive amounts of carbon beyond the reach of our atmosphere. “If the ocean were well mixed overall we wouldn’t have the problem with climate change,” he said. “But the interaction between the deep ocean and the surface is on a very slow cycle.” The goal for a lot of geoengineers is to figure out how to sink atmospheric carbon deep down into the water, where a lot of it will eventually become sediment. Kruger’s limestone plan wouldn’t deliver the carbon directly to the depths, the way the algae plan might have. Instead, the lime would keep more carbon locked into the upper layers of the ocean, allowing time for the ocean’s subduction cycle to carry more of it down into the deep.

Another possible method of pulling carbon down with rocks is called “enhanced weathering.” In chapter two, we saw how intense weathering from wind and rain on the planet during the Ordovician period actually wore the Appalachian Mountains down to a flat plain. Runoff from the shrinking mountains took tons of carbon out of the air, raising oxygen levels and sending the planet from greenhouse to deadly icehouse. The Cambridge physicist David MacKay recommends this form of geoengineering in his book Sustainable Energy—Without the Hot Air. “Here is an interesting idea: pulverize rocks that are capable of absorbing CO2, and leave them in the open air,” he writes. “This idea can be pitched as the acceleration of a natural geological process.” Essentially, we’d be reenacting the erosion of the Ordovician Appalachians. MacKay imagines finding a mine full of magnesium silicate, a white, frangible mineral often used in talcum powder. We’d spread magnesium silicate dust across a large area of landscape or perhaps over the ocean. Then the magnesium silicate would quickly absorb carbon dioxide, converting it to carbonates that would sink deep into the ocean as sediment.

However we do it, enhanced weathering relies on the idea that we could take advantage of the planet’s natural geological processes to maintain the climate at a temperature that’s ideal for human survival. Instead of allowing the planet’s carbon cycle to control us, we would control it. We would adapt the planet to our needs by using methods learned from the Earth’s history of extraordinary climate changes and geological transformations. Of course, this all depends on whether we can actually make geoengineering work.

This diagram illustrates how a number of geoengineering projects could be used to transform the Earth’s climate by drawing carbon out of the atmosphere and reflecting sunlight back into space. (illustration credit ill.17)

There is what Kruger and his colleagues call a “moral hazard” in doing geoengineering research, because it could popularize the idea that geoengineering solutions are a magical fix for our climate troubles. If policy-makers believe that there’s a “cure” for climate change just around the corner, they may not try to cut emissions and invest in sustainable energy. “It’s as if a scientist had some good results while testing a cancer cure in mice, and we started telling kids, ‘Hey, it’s OK to smoke, we’re about to cure cancer,’ ” Kruger said. The point is that we’re very far from being certain that geoengineering would work, and until we’ve got a lot more hard data, we have to assume that the best way to slow down climate change is to stop using fossil fuels.

There’s another worry, too. “There’s a potential for nation-states to see geoengineering activities as a threat,” Cascio cautioned. Harking back to what Driscoll said about how stratospheric reflective particles might cause cooling in some places, but warming in others, Cascio warned that solar management might cause famines in some regions of the world while others cool down into fruitful growing seasons. So one country’s climate solution might be another one’s downfall. A failed experiment in stratospheric particle injection might not just be horrible weather—it might be nuclear retaliation from countries who feel attacked.

To deal with these moral and political hazards, Kruger and several colleagues created the Oxford Principles, a set of simple guidelines for geoengineers to follow in the years ahead. Spurred by a call from the U.K. House of Commons Science and Technology Committee, Kruger met with a team of anthropologists, ethicists, legal experts, and scientists to draft what he called “general principles in the conduct of geoengineering research.” The Oxford Principles call for:

1. Geoengineering to be regulated as a public good.

2. Public participation in geoengineering decision-making.

3. Disclosure of geoengineering research and open publication of results.

4. Independent assessment of impacts.

5. Governance before deployment.

Kruger emphasized that the principles must be simple for now, because geoengineering is still developing. First and foremost, he and his colleagues want to prevent any one country or company from controlling geoengineering technologies that should be used for the global public good. Principles 2 and 3 touch on the importance of openness in any geoengineering project. (The rogue geoengineer in Canada notably violated principle 2, getting absolutely no input from the public before seeding the waters.) Kruger feels strongly that as long as the public is informed and able to participate, they won’t fear geoengineering in the way many people have come to fear other scientific projects, like GMO crops. Finally, the principles aim to prevent unchecked experimentation that could lead to environmental catastrophe, while also avoiding regulations so restrictive that they stifle innovation. Principle 5, “governance before deployment,” speaks in part to Cascio’s concern about countries interpreting geoengineering as an attack. Before we turn the skies white, or fill the oceans with lime, we must form a governing body that allows nations and their publics to consent to change the fundamental geological processes of the world. “There are huge risks associated with doing this, but doing nothing has huge risks as well,” Kruger concluded.

To make Earth habitable for another million years, we will have to start taking responsibility for our climate in the same way we now take responsibility for hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland. Geoengineering of some kind is critical for our survival, because it’s inevitable that our climate will change over time. Certainly we’ll have to adapt to new climates, but we’ll also want to adapt the climate to serve us and the creatures who share the world’s ecosystems with us. If we want our species to be around for another million years, we have no choice. We must take control of the Earth. We must do it in the most responsible and cautious way possible, but we cannot shy away from the task if we are to survive.

Of course, we can’t stop at the edges of our atmosphere. If climate change doesn’t extinguish us, an incoming asteroid or comet could. That’s why we’re going to have to control the volume of space around our planet, too. We’ll find out how that would work in the next chapter.