CHAPTER 3

The Regulatory Need for Tests to Detect EDCs and Assess Their Hazards to Wildlife

3.1.2 Policy Responses to the Initial General Concern: General Strategies

3.2 GENERAL APPROACHES IN SUBSTANCE-RELATED REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS (EU)

3.2.1 Highlighted Role of ED Properties in General Parts of Regulatory Frameworks

3.2.2 REACH: Authorization in Cases of “Very High Concern”

3.2.3 Plant Protection Products: Major Change from Directive 91/414 to New Regulation 1107/2009

3.2.6 Other Regulatory Frameworks Not Primarily Related to Substances

3.3 HOW TO MAKE EDC DEFINITIONS OPERATIONAL FOR SUBSTANCE-RELATED REGULATORY WORK

3.1 EMERGING CONCERNS AND POLICY RESPONSES: FOCUSING ON EDCS AS A LARGE PSEUDO-UNIFORM GROUP OF SUBSTANCES

3.1.1 Regulatory Action Among Public Concern, Policy, Stakeholder Interests, and Scientific Complexity: The Starting Point

This chapter describes how regulatory authorities tackle a prevalent predicament that also applies to the issue of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs).

Missions and mandates of responsible authorities and the commitment of their officers require them to react purposefully to emerging concerns, including those about endocrine disrupters, which the book Our Stolen Future [1] presented in a fairly comprehensive and persuasive way. Chapter 2 provides more details of the large and growing evidence substantiating numerous specific aspects of the general EDC concern.

Effective regulatory measures normally make an impact on stakeholder interests. The greater the affected interests, particularly economic interests, the greater the need for transparent and consistent justification of the corresponding regulatory measure. Due to the checks and balances in all major democratic economies, scientific arguments almost implicitly play an important role justifying any specific action of regulatory authorities, and also essential parts of underlying legislation. In general, the required extent of scientific evidence, or even proof, increases with the weight of interests affected by a regulatory measure. This key role of scientific arguments is still constitutive when applying the precautionary principle and the so-called RRR principle to reduce, refine, and replace testing methods that use animals.

Due to the need to reduce for communication purposes the apparent scientific complexity of the EDC issue, its general perception by the public and policy makers tends to underestimate two crucial points for purposeful regulatory action:

Moreover, this chapter describes the regulatory challenge bridging between a general concern, driven not only by science but also by policy, and the need to respond in various specific regulatory frameworks. The latter may however slightly diverge in some elements of their already established philosophies and conventions regarding risk assessment and risk management. It is hoped that the reader will concur with the authors about the particular role of adequate testing methods and testing strategies in tackling this challenge.

3.1.2 Policy Responses to the Initial General Concern: General Strategies

After policy makers recognized in general that the issue of EDCs merited considerable and concerted action, decision makers of major economies set up research and action plans at national and supranational levels. These policy strategies share a number of similarities, while there is at the same time political will and practical effort to minimize duplication of work. Sections 3.1.2.1, 3.1.2.2, 3.1.2.3, and 3.1.2.4 outline the European and U.S. strategies as well as briefly describe the strategies of Japan and the United Kingdom. These four examples should be read as illustrations, providing a reasonably representative overview of global EDC-related activities, but they certainly do not give a complete compilation. As an interesting aspect with further relevance, the reader should note particulars in tackling individual substances and in referring to testing and assessment methods.

Common to all described strategies is their general reference to work under the auspices of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which is briefly introduced next, and analyzed in its relevance for this chapter in Section 3.3. In September 2009, Denmark hosted an OECD workshop on member countries’ activities regarding testing, assessment, and management of endocrine disrupters. The Copenhagen workshop report provides a comprehensive topical overview, including a number of annexes with a case study report and individual contributions from the EC, Denmark, France, Germany, Japan, Korea, United Kingdom, United States, and industry [4]. Major global activities are also briefly outlined here.

3.1.2.1 European Community Strategy for Endocrine Disrupters

Launch and Implementation of the General Strategy

An important starting point for comprehensive activities at the European level was the workshop “Impact of Endocrine Disrupters on Human Health and Wildlife,” held 1996 in Weybridge, the United Kingdom [5]. Supported by the European Commission (EC); the European Environment Agency; the World Health Organization (WHO) European Centre for Environment and Health; the OECD; national authorities and agencies of the United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, and the Netherlands; as well as industry’s business association European Chemical Industry Council; and the industry-funded scientific organization the European Center for Ecotoxicology and Toxicology of Chemicals, one main workshop outcome was an agreed general definition for endocrine disrupters and potential endocrine disrupters. A wide range of recommendations related mainly to research areas, such as the conduct of wildlife effect studies, the examination of mechanisms and modes of action, the exploration of models for research, the scrutiny of exposure, and the development of methods for the screening and testing of chemicals.

Almost two years later, in 1998, the European Parliament reinforced the science-based workshop recommendations by a resolution, calling on the European Commission (EC) to amend the legislative framework, strengthen the research activities, and disseminate information to the public. In 1999, the Scientific Committee on Toxicology, Ecotoxicology, and the Environment, one of the EC’s scientific committees, provided independent scientific advice with an opinion called “Human and Wildlife Health Effects of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals with Emphasis on Wildlife and Ecotoxicology Test Methods” [6]. In December of the same year, the EC approved the communication document outlining the strategy [7] and thereby launched the “Community Strategy for Endocrine Disrupters—A Range of Substances Suspected of Interfering with the Hormone Systems of Humans and Wildlife.” Progress with implementation was reported in 2001, 2004, and 2007 by further EC documents [8–10] and in August 2011 by the most recent EC Staff Working Paper [11].

As key objectives, the strategy claims to identify the problem, causes, and consequences of endocrine disruption, and to identify appropriate policy action based on the precautionary principle, well grounded with further research, international cooperation, and communication to the public.

By the end of 2010, the Web site of the EC’s research directorate (available at http://ec.europa.eu/research/endocrine/index_en.html) listed 55 completed and 25 ongoing research and development projects related to EDCs and funded by European Union (EU) Framework Programs (FP) 4-7, with a quite wide range of focus (i.e., covering both human health and wildlife-related research focusing at different levels of biological complexity). The EU funding for EDC research peaked with a total budget reaching over €60 million in the fifth FP (1998–2002). Regarding international cooperation, participation in these key activities is listed, illustrating overlap of the EDC issue with other substance issues of regulatory concern:

- Follow-up of the Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety, which entails the setting up of a global inventory of research at the Joint Research Centre in Ispra, Italy, and the publication of a global state-of-the-science assessment report

- The EU–U.S. Science and Technology Cooperation Agreement, under which endocrine disruption is earmarked as one of four priority research topics

- Ratification of the Protocol on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) under the 1979 United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Convention for Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution

- Negotiations toward a global United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) instrument on POPs;

- Implementation of the OSPAR Commission’s Strategy for Hazardous Substances

General Policy Objectives and Initiation of Substance-Related Work

As the most important long-term measure, the EC envisaged amending the EU legislative instruments covering substances including consumer, health, and environmental protection. In November 1998, the EC adopted a report on the operation of four instruments concerning the EC policy on chemicals [12]. With regard to EDCs, both Commission and Council agreed that the strategy on endocrine disrupters will in the longer-term form an integral part of the Community’s overall chemicals policy strategy. Moreover, the report explicitly referred to the instruments in various existing legislation, such as scientific hazard identification and risk assessment; resulting legislative risk management divides mainly into product-oriented, process-oriented, and media-oriented instruments. The EDC strategy attempts to ensure that the mentioned instruments cover EDCs adequately. Under existing legislation, chemicals including many (potential) EDCs are already subject to regulatory measures, usually based on reported toxic effects of these substances without necessarily identifying the underlying mechanisms and modes of action.

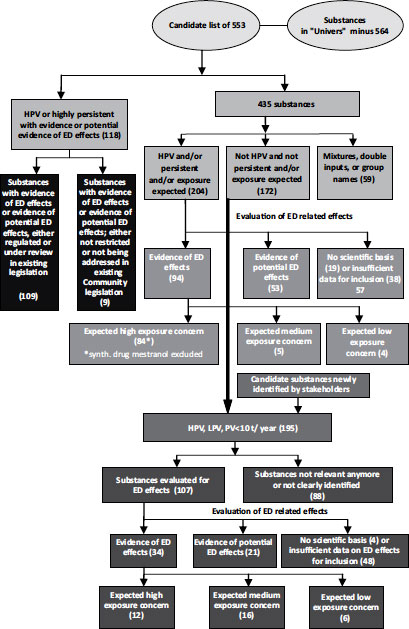

With regard to individual substances, the initial approach of the EC’s strategy was to compile a priority list of substances for further evaluation of their role in endocrine disruption, irrespective of the regulatory frameworks covering any of them. A study commissioned by the EC’s Environment Directorate identified a candidate list of 553 man-made substances and 9 natural and synthetic hormones [13]:

The results of these studies were compiled in a database. (This database is further explained and accessible on the EC Environment Directorate’s Web site, http://ec.europa.eu/environment/endocrine/strategy/substances_en.htm#report3, or can be directly downloaded: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/endocrine/library/database.zip.) Various organizations or published papers or reports had suggested 564 chemicals as potential EDCs: 147 thereof were considered either likely to be persistent in the environment or produced at high volumes. Of these, 66 showed clear evidence of ED activity according to the study criteria (assigned Category 1). A further 52 chemicals showed some evidence of ED activity (Category 2).

In 2001, the EC launched two follow-up studies, the first of which included an in-depth evaluation of 12 substances [14]. Nine of these were industrial compounds for which there was scientific evidence of endocrine disruption or potential endocrine disruption and which were not restricted or being addressed under existing EU legislation. Moreover, the study evaluated all data and information for one synthetic (ethynylestradiol) and two natural hormones (estrone, estradiol). Basically, the study concluded that further testing data and other information would be desirable to confirm or specify a full risk assessment as a basis for potential regulatory risk management measures and proposed further specifications of a general framework for conducting reviews of potential EDCs.

The second study commissioned in 2001 attempted to gather information on 435 substances with insufficient data [15]. For 94 of these, the study noted clear evidence of ED activity (Category 1) and a further 53 chemicals showed some evidence suggesting potential activity (Category 2). Regarding the legal status of these 147 substances, 129 were already subject to bans or restrictions or were being addressed under existing EC legislation—not, however, necessarily related to endocrine disruption.

The EC’s Environment Directorate then contracted another follow-up study [16] addressing the remaining substances not yet evaluated in the previous studies as well as an additional 22 substances identified by stakeholders and experts. According to the categories adopted in the previous studies, this evaluation resulted in allocation to Category 1 (clear evidence for ED activity) for 34 of the newly evaluated chemicals and Category 2 (some evidence suggesting ED activity) for a further 21 substances. As a result, all 553 substances of the original candidate list have now been subject to evaluation and are provisionally grouped as shown in Figure 3.1

FIGURE 3.1 Establishment of the priority list of substances for further evaluation of their endocrine-disrupting (ED) effects. Source: European Commission [10].

The next step will be the conversion of the priority list to an iterative dynamic working list. Hosted at the EC’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) in Ispra, Italy, a Web-based version of the resulting database called “Endocrine Active Substances Web Portal” is planned to be established by mid-2012 [17]. (See also the JRC Web site: http://ihcp.jrc.ec.europa.eu/our_activities/cons-prod-nutrition/endocrine_disrupters/eas_database/info-sources-databases-endocrine-active-substances.)

Interim Conclusions and Prospects

As an interim result of the aforementioned substance evaluations, it appears that the majority of known or suspected EDCs have been subjected to scientific assessments, although these remain informal from a regulatory point of view. It is still up to the actors in each regulatory framework covering the evaluated substances as to how they will incorporate the results of the EC’s evaluations into their day-to-day regulatory business, although doing so eventually will lead to framework-specific regulatory decision-making proposals to be confirmed by the EC.

In 2009, the EC’s Environment Directorate contracted a study project “State of the Art of Assessment of Endocrine Disrupters,” the final report being released in January 2012 [18]. With this project, the EC is apparently attempting to link ongoing work on the identification and characterization of EDCs, based on the most recent scientific knowledge, to clear definitions of (and specific scientific criteria for decision making on) EDCs that are relevant and operational in European regulatory frameworks, such as for industrial chemicals (REACH Regulation 1907/2006), pesticides (Plant Protection Products Regulation 1107/2009 and the new Biocidal Products Regulation 528/2012), and pharmaceuticals. Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 discuss this need in further detail.

While the work on developing a regulatory definition of EDCs is lively and ongoing in the EU, the EC is considering for the next implementation reporting date in 2012 a review of the 1999 strategy’s success together with a proposal for a revised or new strategy, as deemed necessary.

3.1.2.2 U.S. Regulatory Strategy and Implementation

U.S. Legislative Background

In response to concerns voiced over the potential for certain environmental contaminants to interact with hormone receptors and adversely affect reproduction and development, the U.S. Congress held several hearings, which, in 1996, resulted in the passage of two laws affecting the regulation of pesticides and other chemicals. Both of these laws, the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA), which amended the Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act [21 U.S.C. 346a(p)], and the Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 1996 (SDWA Amendments, PL 104-182), contained provisions for screening chemicals for their potential to affect the endocrine system.

Specifically, the FQPA required the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to develop and, within three years, implement a program to “develop a screening program, using appropriate validated test methods and other scientifically relevant information, to determine whether certain substances may have an effect in humans that is similar to an effect produced by a naturally occurring estrogen, or such other endocrine effect as the Administrator [of EPA] may designate” (110 STAT. 1532). FQPA further states that the USEPA “shall provide for the testing of all pesticide chemicals, and may provide for the testing of any other substance that may have an effect that is cumulative to an effect of a pesticide chemical if the Administrator determines that a substantial population may be exposed to such substance.” (110 STAT. 1533)

EPA has interpreted this provision of FQPA as mandating the testing of pesticide chemicals (active and inert ingredients) for estrogenicity and authorizing EPA to obtain testing for:

- Other endocrine effects (e.g., androgen and thyroid; endocrine effects in species other than humans)

- Nonpesticide chemicals to which a substantial human population may be exposed that may have a cumulative effect similar to that caused by a pesticide

Unlike the mandatory provisions in the FQPA to screen chemicals for potential endocrine effects, the U.S. SDWA provided EPA with discretionary authority to test substances that may be found in sources of drinking water to which a substantial population may be exposed.

Given the challenges of meeting the new legal requirements, EPA chartered the Endocrine Disruptor Screening and Testing Advisory Committee (EDSTAC) and charged the committee with providing advice to EPA on how to design a screening and testing program to detect and characterize EDCs. In its report to EPA in 1998, EDSTAC recommended that the scope of the screening program be expanded to include the androgen and thyroid hormone systems, fish and wildlife, and virtually all chemicals to which humans or wildlife could be exposed [19]. The rationale given was that all three hormone systems were essential to development and represented the credible minimum for such a screening program. Wildlife and fish were included because the evidence for endocrine disruption was strongest in environmental species. They also recommended a broad universe of chemicals consisting of pesticides, commercial chemicals and environmental contaminants, because there were some examples of pharmaceuticals, commercial chemicals, and personal care products which had shown various degrees of hormonal activity [19].

To handle such a task, EDSTAC recommended a two-tiered screening system. Tier 1 would be a series of in vitro and relatively short-term in vivo screens to determine whether a chemical has the potential to interact with the estrogen, androgen, or thyroid systems. Tier 1 in vitro assays were also intended to provide some mechanistic data for single pathways, whereas the in vivo assays would capture multiple mechanisms and effects in an intact organism. The results of Tier 1 assays as well as other relevant information are intended to be used to identify candidate chemicals for Tier 2 testing. Tier 2 testing would be a more comprehensive testing in different taxa (mammals, birds, fish, amphibians, invertebrates) covering reproduction, growth, and development. The purpose of Tier 2 testing is to further characterize the effects on the estrogen, androgen, and thyroid hormonal pathways identified through Tier 1 screening by using in vivo studies that establish dose-response relationships for any potential adverse effects for risk assessment.

EDSP Program Development and Implementation

EDSP Assay Validation

The EDSP (Endocrine Disrupter Screening Program) has been developed and implemented in several parts: development and validation of Tier 1 and Tier 2 assays, chemical selection and priority setting, development of regulatory policies, and issuance of test orders to require pesticide registrants and chemical manufacturers to conduct testing and an evaluation of their response.

The most resource intensive activity was the validation of the assays. Out of 14 assays considered by EPA for Tier 1, EPA adopted the assays shown in Table 3.1 for the Tier 1 screen after review by the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) Scientific Advisory Panel.

Table 3.1 Battery of assays for Tier 1 of the Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program after review by the EPA Scientific Advisory Panel

| In vitro |

| Estrogen receptor (ER) binding—rat uterus |

| Estrogen receptor α (hERα) transcriptional activation—human cell line (HeLa-9903) [OECD Test Guideline 455] |

| Androgen receptor (AR) binding—rat prostate |

| Steroidogenesis—human cell line (H295R) [U.S. lead, validated in OECD program] |

| Aromatase—human recombinant |

| In vivo |

| Uterotrophic (rat) [OECD TG 440] |

| Hershberger (rat) [OECD TG 441] |

| Pubertal female (rat) |

| Pubertal male (rat) |

| Amphibian metamorphosis (frog) [OECD TG 231] |

| Fish short-term reproduction [OECD TG 229] |

The individual assays that comprise the EDSP Tier 1 screen were designed to be complementary to one another. As a consequence, a more thorough understanding of endocrine interactions is obtained by the combined analysis of the Tier 1 assays. A fundamental point concerning the interpretation of Tier 1 screening is that multiple lines of evidence are evaluated in an integrated manner during the weight-of-evidence (WoE) evaluation wherein no one study or end point is generally expected to be sufficiently robust to support a decision of whether Tier 2 testing is needed. In presenting the Tier 1 screening approach to the FIFRA Scientific Advisory Panel, EPA illustrated how it was designed with model chemicals of known endocrine action (see www.epa.gov/scipoly/sap/meetings/2008/march/technical_review.pdf). Several illustrations are presented next.

Illustrations of the EPA EDSP Tier 1 Design

The next examples are intended to provide a simple illustration of how the Tier 1 screen was designed as an integrative approach to detect the potential of a chemical to interact with particular endocrine pathways.

Methoxychlor is a pesticide that binds weakly to the estrogen receptor (ER), as compared to its metabolite, 2,2-bis( p-hydroxyphenyl)-1,1,1-trichloroethane (HPTE). The results from the in vitro ER assays and in vivo uterotrophic assay (administered subcutaneously) showed a relatively weak but positive response to methoxychlor. The oral route for the uterotrophic assay is more sensitive due to metabolism of methoxychlor to HPTE. These positive responses were confirmed by the relatively strong positive responses attributed to methoxychlor metabolite(s) in the in vivo female pubertal and fish reproduction assays. The difference in response is due to the route of exposure, as the female pubertal is oral, with HPTE inducing the estrogenic effect. Hence, the consistent positive responses among assays (see Table 3.2) provided evidence that methoxychlor interacts with the estrogen hormonal pathway as an estrogen agonist.

Table 3.2 Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program Tier 1 testing and results for methoxychlor as reviewed by the EPA Scientific Advisory Panel

| Methoxychlor: Estrogen Hormonal Pathway | |

| ER binding (rat uterine cytosol) | Weak binder [64] |

| ERα transcriptional activation (human cell line HeLa-9903) | Positive [65] |

| Uterotrophic (rat; subcutaneous injection, oral) | Positive [66] |

| Pubertal female (rat; oral) | Positive, accelerated vaginal opening [67] |

| Fish short-term reproduction | Positive, induces male vitellogenin and reduces egg production [68,69] |

Vinclozolin is a pesticide that has anti-androgenic effects. In the androgen receptor (AR) binding assay using rat prostate cytosol, vinclozolin gave ambiguous results (a partial binding curve that did not cross the 50 percent binding threshold). Nevertheless, in the Hershberger assay, pubertal male assay, and fish short-term reproduction assay, vinclozolin gave positive results, despite the equivocal results in the in vitro AR assay (see Table 3.3). The difference in response is attributed to metabolism of vinclozolin to the active species M1 and M2. Unlike the in vivo assays, the AR in vitro assay does not have the capacity for metabolism, which apparently led to the equivocal response. In this case, positive responses among the in vivo assays provided evidence over the equivocal response in the in vitro assay to indicate that vinclozolin interacts with the androgen hormonal pathway in an antagonistic way.

Table 3.3 Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program Tier 1 testing and results for vinclozolin as reviewed by the EPA Scientific Advisory Panel

| Vinclozolin: Androgen Hormonal Pathway | |

| AR binding (rat prostate cytosol) | Equivocal, partial binding curve [70] |

| Hershberger (rat) | Positive, antiandrogen [71] |

| Pubertal male (rat) | Positive, delay in preputial separation consistent with anti-androgenic activity [72] |

| Fish short-term reproduction | Negative for anti-androgenic effects but did increase production of estradiol [68,69] |

Ketoconazole is a pesticide and a pharmaceutical that alters steroidogenic enzymes resulting in enhanced progesterone and reduced estrogen and androgen production. In the in vitro steroidogenesis assay (H295R cell line assay), ketoconazole inhibited the production of both testosterone and estradiol. It also provided a full inhibition curve in the recombinant aromatase assay. Ketoconazole is known to inhibit multiple cytochrome P450 enzymes within the steroidogenesis pathway: cholesterol side-chain cleavage (CYP 11A), 17α-hydroxylase (CYP 17) and 17,20-lyase activity, and aromatase (CYP 19). The results of the pubertal female and male assays (alterations in ovarian and testicular morphology, delayed puberty in male) and the fish short-term reproduction assay were corroborated by results in the in vitro steroidogenesis and aromatase assays (see Table 3.4). Hence, the consistent positive responses in the in vitro and in vivo assays provide results that ketoconazole can potentially interfere with the steroidogenic pathway.

Table 3.4 Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program Tier 1 testing and results for ketoconazole as reviewed by the EPA Scientific Advisory Panel

| Ketoconazole: Steroidogenesis | |

| Aromatase (human recombinant microsomes) | Positive, inhibition [73] |

| Steroidogenesis (human cell line H295R) | Positive, reduction estradiol and testosterone [74] |

| Pubertal female (rat) | Positive, ovarian histopathology, increased adrenal weight, no effect on age at vaginal opening [67] |

| Pubertal male (rat) | Positive, delay in preputial separation [72] |

| Fish short-term reproduction | Positive, Leydig cell proliferation [68,69] |

Priority Setting for the First List

The EDSTAC [19] recommended a sorting and prioritization approach that sorted chemical inventories into four categories:

Given that the vast majority of chemicals in commerce would fall into category 2, the EDSTAC provided further recommendations for prioritizing chemicals for Tier 1 screening. To the extent possible, prioritization was recommended to involve a scheme that combined exposure and effects information and would include the use of existing, or predicted, exposure and effects information. With regard to effects information, the EDSTAC encouraged the EPA to evaluate the use of high-throughput screening (HTPS) assays for receptor binding and transcriptional activation and (quantitative) structure-activity relationships [(Q)SARs] for these end points to obtain predictive information for which no chemical data were available to support prioritization. The EPA selected a group of pesticide active and high-production-volume (HPV) inert ingredients as the first list to be screened using exposure potential only because HTPS and (Q)SARs were not sufficiently developed to be used in priority setting at that time. The following criteria were used:

- Pesticide active ingredients: presence in food and water, residential use, and occupational contact

- HPV inert ingredients detected in human and environmental monitoring

On April 15, 2009, EPA issued the list of chemicals for initial screening. It contained 58 pesticide active ingredients and 9 HPV pesticide inert ingredients. Because this first list was not based on any effects information, EPA made it clear that it was not a list of “known” or “likely” endocrine disrupters.

EDSP Policies and Procedures for the First List

EPA developed a set of policies and procedures for test order recipients to follow. These were published along with the final test guidelines in September 2009. EPA issued the first of approximately 750 test orders to the manufacturers and importers over the period October 2009 through February 2010. The test orders required recipients to conduct all of the assays in the Tier 1 battery or submit other scientifically relevant information in lieu of testing. Within 90 days of receiving the test order, test order recipients were required to respond to EPA stating whether they would: generate new data, cite or submit existing data, enter into a consortium to provide the data, voluntarily cancel the pesticide registration or reformulate the product(s) to exclude this chemical from the formulation, claim a formulators’ exemption, or discontinue the manufacture and import of the chemical in question or the selling of it into the pesticide market.

In addition to the test guidelines, which provide guidance to the user on how to conduct each assay, EPA developed Standard Evaluation Procedures (SEPs) for all screening assays which provide guidance for evaluating the conduct of each study and for the interpretation of results (www.epa.gov/endo/pubs/toresources/seps.htm). EPA also published basic principles and criteria for using a WoE approach for evaluation and interpretation of EDSP Tier 1 screening, which includes Tier 1 assay results and other information to identify candidate chemicals for Tier 2 testing [20]. General guidance is also provided on the considerations that will inform the tests and information that may be needed for Tier 2 testing.

EPA has completed reviewing the submission of scientifically relevant information for the first list of chemicals and has publicly posted its decisions regarding what other existing data it has accepted (www.epa.gov/scipoly/oscpendo/pubs/EDSP_OSRI_Response_Table.pdf). Test data are due 24 months from the test order issuance, making most data due in 2012. EPA will review these data and make WoE decisions based on Tier 1 results and other relevant information regarding which chemicals have little or no potential for interacting with the estrogen, androgen, or thyroid systems and which chemicals should be tested in Tier 2. The data from Tier 1 and EPA’s decisions will also be publicly posted.

Evolution of EDSP: Computational Toxicology

The current plan for selecting active ingredients of pesticides for EDSP Tier 1 screening is generally to use EPA’s schedule for reevaluating registered pesticides in the Registration Review program (www.epa.gov/oppsrrd1/registration_review/). However, for pesticide inert ingredients and other chemicals, EPA will consider exposure potential but is also exploring the use of predictive HTPS in vitro and in silico tools that are integrated with exposure-based metrics to determine better which chemicals should be evaluated early in the EDSP. As part of EPA’s computational toxicology and endocrine disrupter research programs, it has been developing in vitro assays, HTPS applications, and (Q)SARs. These predictive tools would be used in a tiered approach to data gathering, screening, and assessment that integrates different types of data (including physicochemical and other chemical properties as well as in vitro and in vivo toxicity data). Such an integrated approach is intended to accelerate significantly EDSP screening and to determine effectively whether higher-tier animal testing is needed to inform risk management decisions.

As a near-term goal to determine priorities effectively for EDSP Tier 1 screening of those chemicals of greatest concern, EPA is considering using various predictive models. For example, one such model is an effects-based expert system for predicting ER binding affinity for food-use inert ingredients and antimicrobial pesticide active ingredients that could be used in a prioritization scheme for screening that was developed by the EPA Office of Research and Development in collaboration with the Office of Pesticide Programs. This expert system was based on in vitro methods to ensure that the (Q)SAR model was sufficiently predictive for the range of structures represented by inerts and antimicrobials. This model conforms to the “OECD Principles for the Validation, for Regulatory Purposes, of (Q)SAR Models” [21] and was the subject of both an OECD expert consultation, “Evaluate an Estrogen Receptor Binding Affinity” [22], and an FIFRA Scientific Advisory Panel external peer review [23]. This expert system for ER binding can be readily expanded to address additional chemical inventories. Although this system is specific to ER binding affinity, the underlying approach could be applied to the development of training sets for other nuclear receptors to expand further hazard-based prioritization schemes.

EPA has additional research ongoing within its ToxCast program to develop HTPS assays to assist in the prioritization of chemicals for targeted in vivo testing. The ToxCast program includes 467 HTPS assays that have assessed over 300 environmental chemicals. A predictive method, called Toxicological Priority Index (ToxPi) is being developed to assist in EDSP priority setting that incorporates ToxCast bioactivity profiles (i.e., inferred toxicity pathways), dose estimates and chemical structural descriptors to calculate toxicity potentials [24]. ToxPi provides a visual representation of the relative contribution of each data domain and overall priority score toward providing a WoE framework to support prioritization for in vivo testing. Although ToxPi can assist in prioritizing chemicals for the EDSP, it is not limited to endocrine toxicity but has potential utility for prioritization of a broader array of toxicities. In an iterative process, HTPS data can be used to support development and validation of (Q)SAR-based expert systems for predicting toxicity, including endocrine effects.

In conclusion, transition toward new integrative and predictive techniques makes greater use of existing data that can in turn be used to allocate resources better by prioritizing chemicals where additional in vitro or in vivo testing may be needed. Over time, these new technologies may replace some or all of the EDSP Tier 1 screens.

3.1.2.3 Japan’s Endocrine Disrupters Strategy

In May 1998, the Japanese Ministry of the Environment (MOE) summarized its basic policy on environmental endocrine disrupters in “The Strategic Programs on Environmental Endocrine Disruptors” (SPEED ’98).

The major elements of this strategy are (1) to promote field investigations into the present state of environmental pollution and of adverse effects on wildlife of ED chemicals; (2) to promote research, screening, and testing method development; (3) to promote environmental risk assessment, risk management and information dissemination; and (4) to strengthen international networks.

Sixty-seven suspected chemicals (65 chemicals in the list updated in 2000) were listed in this strategy. Suspected chemicals were monitored for water, sediment, soil, air, and aquatic organisms (such as fish and shellfish), wildlife, and foods. Monitoring results were used to select chemicals for testing, to determine doses, and to conduct risk assessment. No cause-and-effects relationship was drawn between the detected body burden and anomaly in each species. However, abnormal reproductive organs were observed in the snail species Thais clavigera over a broad coastal area, caused by organotin compounds.

Test methods were developed for different species. Screening tests were conducted and hazardous properties were evaluated for priority chemicals using fish and rats. With the fish species medaka (Oryzias latipes), in vitro ER binding assays were conducted for selected chemicals, as well as vitellogenin (VTG) assays, partial life cycle tests, and full life cycle tests. In the full life cycle test, nonylphenol, octylphenol, bisphenol-A, and o,p′-DDT induced adverse effects on medaka such as testis-ova formation and reduction of fertility. In one-generation tests with rats, no clear effects were observed at doses considered equivalent to the estimated human exposure levels.

SPEED’98 delivered a certain level of progress in understanding endocrine disruption by chemicals, while focusing on hazardous properties of chemicals. Concurrently, misunderstandings arose that all the priority chemicals on the list are identified as endocrine disrupters.

The Enhanced Tack on Endocrine Disruption (ExTEND 2005) was adopted as follow-up strategy in March 2005. The list of target chemicals for assessment has not been further developed in this strategy. Rather, the key elements of this strategy were to promote (1) basic research and field observation, (2) testing and risk assessment for chemicals having potential for exposure (i.e., detected in the environment), and (3) correct information sharing and risk communication. Seven major areas were pursued:

ExTEND 2005 focused on research for fundamental knowledge of endocrine disruption after public concerns calmed down. Applications for the two research categories, fundamental research and research for the biological observation of wildlife, were publicly invited, and 38 studies were adopted during the five years. Test methods for assessment of ecological effects were developed for fish, amphibians, and invertebrates. Target chemicals were selected after the results of environmental monitoring. Reliability evaluations of the existing knowledge were conducted, but a framework for assessment was not developed.

In July 2010, EXTEND 2010 was adopted as a new program by maintaining the appropriate parts of ExTEND 2005 and adding necessary improvements. The aims are: (1) to assess the environmental risk of ED effects of chemicals and to take appropriate management measures; (2) to accelerate the establishment of assessment methodologies and implementation of assessment itself; (3) to put priority on ecological effects and also consider risks to human health caused by chemicals in the environment; and (4) to strengthen international cooperation by seven major fields of activities:

The aims of EXTEND 2010 are to assess the environmental risk of ED chemicals and to take appropriate management measures. Establishment of assessment methodologies and implementation of assessment itself should be accelerated. Research activities in EXTEND 2010 are expected to contribute to implementation and improvements of regulatory risk assessment. MOE expects significant research cooperation among scientists in the world.

3.1.2.4 United Kingdom’s Approach to Endocrine Disrupters

As a starting point, after evaluation of all data and information available in the mid-1990s, responsible U.K. authorities concluded that the most evidence for ED effects existed for the aquatic environment.

Exposure of marine invertebrates, especially mollusks such as the dog whelk (Nucella lapillus), to the anti-foulant tributyltin (TBT) provides one of the best-documented examples of an ED impact caused by an environmental contaminant and one of the few demonstrated cases of a population-level effect. TBT was conclusively shown to cause imposex (imposition of male sex organs on females), a condition that led to severe population declines and local extinctions of N. lapillus in many coastal areas in the United Kingdom and Europe [25–27].

Until the mid-1990s, there was limited other work on endocrine disruption in the U.K. marine environment on which policy could be based. However, Lye et al. [28] demonstrated induction of the egg yolk protein, VTG, an indication of estrogenic impact in male flounder (Platichthys flesus) exposed to sewage effluent in the Tyne Estuary. These results were confirmed by further laboratory and field studies conducted by the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (funded by the then Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food), which also indicated the effect was most severe in estuaries such as the Tees, Mersey, and Tyne; by comparison, only moderate effects were seen in the estuaries of the Humber, Clyde, Thames, and the clean reference site river Alde [29].

Building on this work, the EDMAR (Endocrine Disruption in the Marine Environment) Research Program [30] was the first large-scale attempt to assess the degree of impact of endocrine disruption in the U.K. marine environment; it widened the number of species studied and the range of field investigations and attempted to identify causal links.

EDMAR confirmed that endocrine disruption was occurring in some marine species in certain locations. It also provided further evidence that some species seem not to be affected, or at least are less vulnerable than others: 187 shore crabs (Carcinus maenas) from a range of clean and contaminated sites were assessed for the presence of VTG. While a high percentage of the females gave a positive result, none of the males was positive. However, it was not possible to determine the overall significance of the findings with regard to population impacts. This is not surprising, given the difficulties in demonstrating effects at this level of biological organization.

In 2002, research funded by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), the Environment Agency, the water industry, and U.K. research councils confirmed earlier findings of estrogenic activity in U.K. sewage effluents, linked to the presence of intersex (presence of female ovarian tissue in male testes) in roach fish (Rutilus rutilus) in U.K. rivers [31]. In laboratory studies, severely feminized male roach produced fewer and less viable sperm than control fish, with a consequent reduction in their fertility (in vitro). Similar effects were also reported in a second fish species, the gudgeon (Gobio gobio), although to a lesser extent. The causal substances identified included the natural human hormone 17β-estradiol and the synthetic hormone ethynylestradiol (a component of birth control pills). In some locations, the synthetic surfactant nonylphenol was also implicated.

Defra and the Environment Agency also funded the Endocrine Disruption in Catchments Research Program to investigate, among other objectives, whether fish populations in U.K. rivers were at risk from sewage-derived ED chemicals. Within this program, Pottinger et al. [32] found that two indicators of performance (specific growth rate and RNA:DNA ratio) in a resident stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) population in the river Ray, Wiltshire, were higher in fish downstream of a sewage treatment works following remediation of the effluent with granular activated carbon. Additionally, Harris et al. [33] demonstrated that severely intersex wild roach (Rutilus rutilus) were less able to produce offspring in competitive reproduction situations compared to mildly intersex individuals; they concluded that feminization of male fish was likely to be an important determinant of reproductive performance in rivers where there was a high prevalence of moderately to severely feminized males.

In the United Kingdom, the basic policy approach adopted was to institute a program of research, funded both interdepartmentally and by individual departments, to address the recognized gaps in knowledge. At the same time, particular chemicals found to be strongly implicated as endocrine disrupters would be proposed for full risk assessment under European regulations, leading to controls across the European Union if deemed necessary; this has been done in several instances—for example, nonylphenol, bisphenol A, and two polybrominated diphenyl ether (PDBE) flame retardants.

3.1.2.5 OECD’s Special Activity on Endocrine Disrupter Testing and Assessment

In 1998, OECD established a Special Activity on Endocrine Disrupter Testing and Assessment (EDTA), under the umbrella of the Test Guidelines (TG) program within OECD’s Environment Directorate, Environment Health Safety Division. This activity was launched at the request of the member countries to ensure that testing and assessment approaches for endocrine disrupters would not substantially differ among countries. Consequently, the objectives of the EDTA activity are to:

- Provide information and coordinate activities

- Develop new and revised existing TGs to detect endocrine disrupters and characterize endocrine-mediated effects

- Harmonize hazard and risk characterization approaches

The work on endocrine disrupters, testing, and assessment is managed by the Advisory Group on Endocrine Disrupters Testing and Assessment (EDTA AG). This group is composed of national experts, nominated by the National Coordinators of the OECD TG program, including the EC. Other stakeholders also participate, including the Business and Industry Advisory Committee, environmental nongovernmental organizations, and the International Council on Animal Protection in OECD Programmes.

Three Validation Management Groups (VMGs), which report to the Working Group of the National Coordinators of the TG program, have been overseeing and managing the conduct of the practical validation work:

So far, validation and regulatory acceptance have been achieved for several test methods for screening and testing chemicals for their ED potential, and these methods have been adopted (or updated) between 2007 and 2011 as OECD TGs. These guidelines cover mammalian, fish, amphibian, invertebrate, and in vitro tests. For the hazards to wildlife, TG 211 [34], TG 229 [35], TG 230 [36], TG 231 [37], TG 233 [38], and TG 234 [39] are directly applicable. Data from other TGs may add to the WoE assessment but are not directly relevant to wildlife testing.

A number of other new or revised TGs were in the validation stage in 2011; they address, for example, fish partial or full life cycle tests, as well as partial or full life cycle tests on invertebrates (e.g., mollusks). The validation of test methods required active involvement and significant resources in laboratories in member countries and industry; some of the test methods were validated using multiple species, according to the regulatory preferences in OECD member countries. The adoption of TGs is a major achievement for OECD member countries: it implies the Mutual Acceptance of Data [40] produced using these TGs, which should avoid duplicative testing.

A conceptual framework [4] sorting information by level of biological complexity was initially adopted in 2002. It was revised in 2012 to reflect the current understanding and practice for the testing and assessment of potential endocrine disrupters. In parallel, a draft guidance document on standardized TGs for evaluating chemicals for endocrine disruption has been adopted in 2012 [75], as an application of the conceptual framework under various scenarios of data availability; it is a guide to the appraisal of existing data and an evaluation of the need (or not) for additional testing. Finally, a fish testing strategy, covering among other things the screening and longer-term testing of fish for potential endocrine disrupters, was adopted in 2012 in the Fish Toxicity Testing Framework [76].

3.1.2.6 Global Activities

In February 1997, the Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety made a number of recommendations to the member organizations of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC), notably the International Programme of Chemical Safety (IPCS) and OECD, to address the issues related to emerging concerns about potential adverse effects resulting from EDC exposure. The IPCS, which is jointly promoted by IOMC members—that is, WHO, UNEP, and the International Labor Organization, developed and published in 2002 a global assessment of the state of the science of endocrine disrupters [41].

At that time, the 180-page document provided a sound analysis of the global peer-reviewed scientific literature where the associations between environmental exposures and adverse outcomes had been demonstrated or hypothesized to occur via mechanisms of endocrine disruption. The assessment did not consider endocrine disruption as a toxicological end point per se but as a functional change that may lead to adverse effects. The preparation of the assessment report resulted also in widely accepted definitions of endocrine disrupters and potential endocrine disrupters. At the same time, the document explicitly refrained from assessing EDC-related test methodology and from addressing risk assessment and risk management issues.

In 2009, UNEP and WHO started activities to prepare an update of the aforementioned publication. In the planning phase, involved organizations considered following a tiered approach, with a focused WHO report on selected human health issues to be published as a first step [77] and a full update as a second step. This comprehensive subsequent publication is intended to cover areas such as exposure, identification and evaluation of EDCs, mechanisms of action, and effects on health and wildlife.

With the intention of preparing a major policy signal, UNEP and WHO nominated in 2010 the issue of “international cooperation to build awareness and understanding and promote actions on EDCs” as an emerging issue to be considered by the third session of the International Conference on Chemicals Management in May 2012. ICCM3 added then EDCs to the list of ‘emerging policy issues’ under the United Nations’ Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM), and adopted a resolution asking the UN’s chemicals management bodies to develop an action plan for reducing exposure to and effects of EDCs.

3.2 GENERAL APPROACHES IN SUBSTANCE-RELATED REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS (EU)

3.2.1 Highlighted Role of ED Properties in General Parts of Regulatory Frameworks

With brief analyses of the major substance-related European regulatory frameworks, this section examines how EDCs are being addressed and what the most recent developments are. As indicated earlier, the basic philosophy of the relevant frameworks at the EU level, which are essentially regulations, directives, and corresponding technical guidance documents, is predicated on the tools of scientific hazard identification and risk assessment. The basic objectives of using these tools are to justify legislative measures and to tailor specific measures adequately for achieving effective and efficient risk management.

The term “hazard” refers to intrinsic properties of a substance. Describing the nature of adverse effects caused by these properties, and how the severity for each kind of effects depends on dose or concentration of the substance evaluated, is the essence of hazard characterization. Normally, the most important basis for this is test data and other scientific information. For risk assessment, the hazard information is related to exposure assessment, which evaluates the nature and probability for biological systems to be exposed to this substance. In reality, this rather simple principle gives rise to considerable challenges, in particular due to—potentially multiple—data gaps, uncertainties, and complexity both of biological effects and exposure scenarios. An increasing number of regulatory frameworks attempt to tackle these kinds of shortcomings by two basic approaches. One is to apply the precautionary principle as specified by the EC [42]; this instrument is not in fact a separate approach but an overarching element when developing risk management measures to protect the health of humans and the environment. Another increasingly introduced element is to omit the exposure assessment and limit the grounds for risk management to confirmation of specific hazard classes in cases of particular concern about the (potential) severity and nature of effects; particular uncertainties combined with the concern in question may provide an additional argument for this approach. Several regulatory frameworks similarly apply this hazard-based risk management approach to CMR, POP, and PBT substances.

One key issue in ongoing debates about adequate risk management of EDCs relates to the question of whether endocrine disruption should be considered equivalent to CMR, POP and PBT properties from a scientific and regulatory point of view. As the EC stated in its communication on the EDC strategy’s implementation [43], the issue of endocrine disrupters was to be addressed specifically in the context of new and existing legislation in the field of water policy and as outlined in the White Paper on a strategy for a future chemicals policy [8].

3.2.2 REACH: Authorization in Cases of “Very High Concern”

The European Regulation 1907/2006 on Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) introduced a number of regulatory elements, which apply to commercial chemicals for the first time. Moreover, REACH is the first regulatory framework covering all relevant industrial chemicals. Several of these elements and procedures are highly integrated with the objective to establish chains of responsibilities throughout a substance’s life cycle. This imposes challenges to all actors involved, and also results in a number of indirect effects on marketing and use of chemicals. The EC itself and other parties repeatedly refer to REACH as the most ambitious legislative project for chemicals yet [44–47]. Since early 2009, REACH has been complemented by the new Regulation 1272/2008 on Classification, Labeling and Packaging of Substances and Mixtures (CLP).

All of the roughly estimated 25,000 to 30,000 commercially relevant chemicals will be registered by 2018, and each substance or mixture has to be classified and labeled within one month after being placed on the market. In contrast, the framework will identify relatively few substances of very high concern (SVHC), at most a few hundred within the next few years. The authorization procedure applies to only a subset of SVHC (see below), but is a real novelty for commercial chemicals. Despite its limited focus on few substances with particularly concerning properties and relevance, this new procedure inherits an outstanding role in providing for adequate risk management of these substances. Under the new provisions, they are excluded from any use unless the EC grants authorization for specific uses and applicants, under particular conditions.

According to REACH Article 55, the aim of authorization “is to ensure the good functioning of the internal market while assuring that the risks from substances of very high concern are properly controlled and that these substances are progressively replaced by suitable alternative substances or technologies where these are economically and technically viable.” Under Whereas point 69, the regulation states: “To ensure a sufficiently high level of protection for human health, including having regard to relevant human population groups and possibly to certain vulnerable sub-populations, and the environment, substances of very high concern should, in accordance with the precautionary principle, be subject to careful attention.”

REACH subjects any use of a substance to the authorization procedure, when this substance is listed in Annex XIV. Before the EC decides to include a substance in Annex XIV, it has to be identified as SVHC. After confirmation of this status, the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) has to recommend the inclusion of a SVHC into Annex XIV under consideration of several technical and practical aspects, like tonnages, dispersiveness due to uses or properties, or the agency’s capacities to handle authorizations in the given timeframes. While the protracted procedures for inclusion in Annex XIV are here of no specific interest, REACH Article 57 is of particular importance as it provides criteria for identifying SVHC, and also mentions EDCs. Substances may be included in Annex XIV if they:

(Note that the original legal text has been summarized slightly here to make it read more easily.)

Thus Article 57(f) refers to ED properties as possible reason for very high concern, while additionally referring to equivalency of this concern to CMR, PBT, and vPvB substances and further referring to case-by-case identification. The latter is a merely practical need as there are at present neither criteria nor categories for regulatory classification of endocrine disrupters, nor an annex providing established regulatory criteria. In contrast, these are available as legal classification criteria for CMR substances (Annex I of CLP Regulation) and in REACH Annex XIII for PBT and vPvB substances.

Moreover, comprehensive technical guidance related to CMR, PBT, and vPvB substances accompanies the REACH and CLP Regulations on how to interpret the legal criteria, how to evaluate test results in comparison to the criteria, and how to generate decision-relevant information in case of data gaps. With regard to ED properties, toward the end of 2012 still pending on the outcome of comprehensive activities on EC level (cf. Section 3.1.2.1), available technical guidance for REACH is very limited, namely concerning instructions on the assessment of available information on endocrine and other related effects, appended to hazard end point–specific guidance about how to meet the information requirements set by REACH [48]. As the standard information requirements specified by REACH do not cover any testing or other data specifically related to endocrine activity, this technical guidance applies only to substances with information available beyond the standard requirements. However, even in the latter case, no criteria are provided concerning which cases of ED properties have to be regarded as of regulatory concern according to Article 57(f).

Apart from the still-open issue of identifying EDCs under REACH according to the regulatory requirement of Article 57(f), another aspect is of particular significance for the methodology of EDC identification: the REACH authorization procedure foresees specific conditions for those substances for which it is not possible to determine a safe level, which is normally corroborated by exposure levels below toxic thresholds. Without safe levels an authorization “may only be granted if it is shown that socioeconomic benefits outweigh the risk to human health or the environment arising from the use of the substance and if there are no suitable alternative substances or technologies.” This procedure is also called the socioeconomic route of authorization according to REACH Article 60, paragraphs 3 and 4, in contrast to the so-called route of adequate control, when the applicant has to demonstrate that use conditions guarantee exposure below oxic thresholds.

Finally, according to REACH Article 138, paragraph 7, the EC has to review by June 2013, through consideration of the latest scientific knowledge, if EDCs should in general be subjected to the socioeconomic authorization route. In other words, an adequate methodology for EDC identification under REACH has to provide for clarification about the general presence or absence of safe regulatory exposure levels for EDCs.

In summary, REACH requires two key issues to be clarified by adequate EDC regulatory identification and characterization: (1) clear and consistent case-by-case justification for categorizing an EDC as substance with very high concern equivalent to CMR, PBT, and vPvB substances, thus subjecting it to the authorization regime; and (2) scientific clarification about whether safe regulatory thresholds can be determined for EDCs in general or for specific subgroups of EDCs, thus allowing for authorization based on adequate control.

3.2.3 Plant Protection Products: Major Change from Directive 91/414 to New Regulation 1107/2009

A paradigm shift in regulatory decision making was introduced with the new pesticide regulation 1107/2009 (to be applied in the EU from June 14, 2011) in order to protect both humans and wildlife from potential threat of ED plant protection products (PPP). Regarding wildlife, the new regulation requires:

An active substance, safener or synergist shall only be approved if, on the basis of the assessment of Community or internationally agreed test guidelines, it is not considered to have endocrine disrupting properties that may cause adverse effects on nontarget organisms unless the exposure of nontarget organisms to that active substance in a plant protection product under realistic proposed conditions of use is negligible. (EC Regulation 1107/2009, Annex II, 3.8.2)

The precedent pesticide directive 91/414, in contrast, did not explicitly address endocrine disruption, neither with regard to the standard data requirements nor in the uniform principles for evaluation and authorization (Annex VI). However, the widely accepted perception under directive 91/414 was explicitly laid down in two associated guidance documents on aquatic ecotoxicology [49] and on birds and mammals risk assessment [50], respectively:

Endocrine disruption is to be viewed as one of the many existing modes of action of chemicals and thus can be assessed in the normal conceptual framework. The environmental assessment is based on the ecological relevance of the observed effects, independently on the mechanisms of action responsible for such effects. Therefore, the general procedure for risk assessment can also be used for endocrine disrupters.

Authorization for pesticides with ED properties could thus be granted according to directive 91/414 if the outcome of the risk assessment excludes “any long-term repercussions for the abundance and diversity of nontarget species.” The risk-based approach as a general principle in decision making therefore required a quantitative comparison of the expected exposure of nontarget organisms from the intended PPP use with established thresholds for ecotoxicologial effects—being them mediated by an endocrine or any other (for wildlife typically unknown) mode of toxic action. Moreover, the standard assessment (extrapolation) factors as required by Annex VI of directive 91/414 to account for general uncertainties inherent to the risk assessment as well as risk mitigation measures intended to reduce exposure of nontarget organisms (e.g., spray drift reduction) have been considered as appropriate in decision making on ED PPPs too.

However, the political demand of a more precautionary oriented decision making refused this risk-based approach and established the so-called endocrine cut-off criterion, as cited earlier in the new pesticide regulation 1107/2009. A hazard-based approach is now required in decision making (i.e., only the proven presence or assumed absence of ED properties shall be decisive for a [non]authorization of a given PPP). The political intention for this paradigm shift in decision making is generally creditable and yielded quickly an increased awareness to the endocrine issue of all stakeholders involved in PPP authorization as a clear benefit. But immediate implementation of the new hazard-based approach in decision making on PPP authorization in the EU is hampered for two main reasons:

3.2.4 Biocides

Until August 2013, Directive 98/8 is the European regulatory framework concerning the placing of biocidal products on the market. There is only one single reference to endocrine disruption in this legal text, which was adopted before the 1999 launch of the EC strategy for endocrine disrupters. In Annex VI of the directive, setting out the common principles for evaluation of dossiers for biocidal products, the subsection on evaluation of effects on the environment allows the omission of a full risk assessment and characterization if the data for hazard identification do not lead to regulatory classification. This omission is, however, not possible in the case of “other reasonable grounds for concern,” such as, for example, “bioaccumulation potential,” “persistence characteristics,” and “endocrine effects.” Correspondingly, only few, rather general and vague references to endocrine activity or endocrine disruption are provided in currently applicable technical guidance documents accompanying the biocides legislation.

The new European biocidal products regulation 528/2012 applies from September 2013 and provides more explicit references to EDCs. In Article 5 on exclusion criteria, point (d) of paragraph 1 refers, the identification of a substance as having ED properties to REACH Article 57(f) and thus encompasses similar open issues as outlined in Section 3.2.2. This reference appears even vaguer in view of the fact that active biocidal substances will in most cases have specific and intended modes of biological action to serve their purpose, possibly also specific endocrine mechanisms of action, like ecdysone receptor agonists or juvenile hormone mimics (see Section 3.2.3). Nevertheless, as counter-exception, a substance identified as having ED properties in the sense of the legal text could be listed in Annex I as a permitted active ingredient under further preconditions laid out in Article 5, paragraph 2(a)-(c).

In summary, the new EU regulatory framework for biocides explicitly refers to ED properties as possible cut-off criteria but, compared to REACH, includes even less clarification about the rationale and methodology for confirmation of an EDC meeting the regulatory criteria for exclusion from authorization, or for possible counter-exceptions. Moreover, the new regulation raises the question about why no closer links are established to the other major framework for pesticides (i.e., the regulation for PPPs) instead of the explicit reference to REACH covering mostly substances without any specific (intended) mode of biological action.

3.2.5 Pharmaceuticals

The European regulatory frameworks currently in force for pharmaceuticals do not explicitly refer to endocrine disruption. However, like active ingredients in biocidal and plant protection products, pharmaceuticals in most cases intentionally exert very specific modes of biological action in target organisms and may unintentionally affect nontarget organisms as well. In particular, several groups of synthetic hormones are clearly EDCs according to agreed scientific definitions, and some are causing major environmental impacts, even though they are intended for therapeutic applications in the fields of veterinary and human medicine.

The general approach for evaluating potential adverse effects of pharmaceuticals on wildlife is essentially risk-based [53–55]: In phase I, a provisional exposure assessment determines predicted environmental concentrations (PECs) and compares these with a so-called action limit of 0.01 μg/L. If PECs are below the action limit, the regulatory guidance assumes that environmental risks due to the medicinal product under consideration are sufficiently unlikely, and the assessment stops. PECs above the action limit of 0.01 μg/L require an evaluation of fate and effects of the active ingredient in phase II. A rather vague temporizing clause also allows proceeding to phase II with PECs below the action limit if known effects of related substances or study results indicate an unusually high potential for ecotoxic effects. This clause is, however, hardly used in regulatory practice. In phase II, the environmentally relevant hazardous properties are then identified and characterized on the basis of standard ecotoxicological testing methods and all other available information, which in the case of pharmaceuticals is quite comprehensive for toxicological effects. Interlinking the hazards to exposure assessment, the evaluation concludes with risk assessment and risk characterization. In case of apparently specific modes of action, such as endocrine activity, the regulatory framework and accompanying technical guidance aim for tailored risk assessment with specific consideration of relevant toxicological information. Approval of medicinal products for veterinary use may require specific risk reduction measures or may even be refused on grounds of predicted environmental risks. In contrast, approval of medicinal products (including EDCs) for human use is not subject to substantial risk management concluded from environmental assessment, according to current pharmaceutical legislation. However, certain limited risk reduction measures may be imposed. For example, based on considerations of an environmental risk due to disposal of used contraceptive bandages for skin adhesion containing ethynylestradiol, companies and authorities may agree to equip product packages with instructions for proper waste handling.

3.2.6 Other Regulatory Frameworks Not Primarily Related to Substances

The regulations considered earlier in this chapter are central in substance-oriented regulation. Still, it should be mentioned that other regulations are relevant for certain endocrine disrupters (e.g., TBT in ships, Commission Regulation, 536/2008), certain uses of substances (e.g., cosmetics, EC 1223/2009), certain geographical regions (e.g., OSPAR), or environmental compartments (soil, sludge, water, etc.).

Among the latter it is relevant to mention Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for the EC action in the field of water policy, in short the Water Framework Directive (WFD). The directive establishes the legal framework to protect and restore clean water across Europe and ensure its long-term, sustainable use. By targeting priority substances, the WFD focuses on individual pollutants or groups of pollutants that present significant risk to or via the aquatic environment. For these substances environmental quality standards are set according to the newly developed guideline [56] that is derived according to the criteria established in the REACH guidance documents, including those for EDCs. At present, 33 chemicals are categorized as priority substances, 13 are designated as priority hazardous substances (PHSs) due to their PBT properties. Although strict criteria are lacking, the potential to interfere with the hormonal systems of humans and wildlife (i.e., EDCs) could also be a criteria for classification as PHSs. Although included for other reasons, several substances from the EU list for suspected endocrine disrupters are among the 33 priority substances. The EC is currently evaluating several possible endocrine disrupters for inclusion in the list of priority substances.

3.3 HOW TO MAKE EDC DEFINITIONS OPERATIONAL FOR SUBSTANCE-RELATED REGULATORY WORK

As illustrated by several examples provided in the previous sections, the challenge to develop and agree adequate and operational definitions and specific scientific decision criteria for EDCs still has to be tackled in substance-related regulatory frameworks. Indeed, widely agreed scientific definitions for EDCs are available. The most frequently used and adapted are the ones developed for endocrine disrupters and potential endocrine disrupters by WHO [41] as a slight modification of the Weybridge definition [5], and many legislative frameworks explicitly refer to endocrine activity and endocrine disruption as properties that merit specific regulatory attention. Nevertheless, a number of key issues have still to be clarified. In the report on the state of the science on endocrine disrupters commissioned by the EC [18], the authors acknowledge that the so far internationally agreed and validated testing methods cover only a limited range of the foreseeable ED modes and mechanisms of action. Published in January 2012, the report still states that regulatory decisions about EDCs will have to rely on WoE procedures which are yet to be developed. Pertinent work is ongoing in several EC working groups, probably proceeding well into 2013.

With a view to the scope of this book and this chapter in particular, this section should be read keeping in mind the interrelation between regulatory questions to be answered and implicit or explicit specifications of testing and assessment methodology required to provide scientific answers to these regulatory questions. This should also help to clarify which questions instead require policy answers. The latter issue merits particular attention and differentiation: it is mainly a policy-driven decision to tackle certain groups of substances like EDCs, howsoever selected and named, with particular regulatory procedures and with the aim of addressing particular public and academic concerns. It is nevertheless a task of scientific work to develop clear criteria and identification methodology for such a substance group. The challenge is that for effective frameworks, both policy and science have to cooperate and communicate very closely, preferably with iterative procedures, but without glossing over the differences between scientific and policy arguments.

In Europe, at the end of 2012, the main drivers for regulatory discussion of the EDC issue are the new Regulation 1107/2009 for PPPs and the REACH regulation for commercial chemicals. Apart from an urgent need to develop practice for procedures already legally in force, both regulations foresee a need for the EC to conduct specified reviews of the EDC issue and to develop amended legislation if needed, by June (REACH) and December (PPP) 2013. Most other European regulatory frameworks either in essence refer to the REACH and PPP regulations or these other frameworks less urgently need regulatory clarification of endocrine disruption as they do not (attempt to) apply particular procedures to EDCs.

Under the new PPP regulation, active substances and auxiliary substances are excluded from authorization when they are endocrine disrupters (unless exposure is negligible). This clear cut-off provision requires consistent and precise definition of the borderline between endocrine disruption and mere endocrine activity. Moreover, workable management approaches are needed for EDCs that are intentionally designed to exert very specific, possibly endocrine, mechanisms and modes of action to affect target organisms.

The REACH Regulation requires immediate clarification to achieve consistent case-by-case identification of EDCs as substances of very high concern according to Article 57(f). This also requires scientific arguments related to the equivalency of the concern for identified EDCs, compared to CMR, PBT, and vPvB substances. Furthermore, it is hoped that by 2013, science will be able to provide clarification about whether particular groups (or all) EDCs are susceptible to the determination of safe regulatory levels.

With a view to the most widely agreed definition of EDCs—“An endocrine disrupter is an exogenous substance or mixture that alters function(s) of the endocrine system and consequently causes adverse health effects in an intact organism, or its progeny, or (sub)populations” [41]—there are still areas to be clarified further and agreed with the aim of achieving a comprehensive, consistent, scientific description that can serve as a starting point for any specification of an EDC as required by particular regulatory frameworks. For regulatory decision making, the focus is slightly different from cutting-edge scientific research. While science strives to identify further open questions and might be particularly attracted to more advanced methods and research areas, regulatory day-to-day business has to make decisions even in the face of considerable uncertainties and research or testing gaps. The regulatory focus is rather on the extent, relevance, and interdependency of uncertainties with a view to the specific nature of the individual decision. Thus, of particular relevance for substance-related regulatory frameworks are clarification and agreement of the next issues, many of which have implications for testing and assessment methodology:

- Most current test methods are limited to detecting sexual-endocrine and thyroid endocrine mechanisms of action. There is a need to address other relevant hormone systems, such as the glucocorticoid system, or unique hormonal systems confined to taxonomic groups other than vertebrates, and compare their relevance with the much better investigated mechanisms of action.

- Research should provide more clarity about the conservatism of endocrine mechanisms and about the range of potencies for given EDCs within vertebrates, with a view to clarifying the need to test different taxonomic groups, such as fish, amphibians, birds, and others.

- There is a need to agree on adversity or nonadversity of particular effects detected by means of testing methods, including agreement on the role of indicative effects, such as biomarker responses, for further testing and assessment. This is a continuous task, progressing alongside further development of testing methods, and potentially not fully answerable without policy and framework-specific risk management considerations.

- Recently developed methods, including metabolism and toxicokinetics as detected by in vitro methods and quicker (three- to four-day) in vivo methods (e.g., measuring gene expression for targeted pathways), should be investigated with a view to reducing the numbers of test animals required and possibly testing costs.

- With regard to fish life cycle testing, further research needs to clarify potential differences of results between one-generation and multigeneration tests. Some evidence suggests similar sensitivity, but when testing strongly bioaccumulative substances, multigeneration tests may be more sensitive. In regulatory practice, multigeneration tests have to be limited to the essential minimum because of their very high resource and animal consumption.

- Each effort at harmonization among different regulatory frameworks has to be weighed against possibly diverging regulatory philosophies, histories, and assessment cultures of a specific legislation. Again, careful differentiation of scientific and policy arguments is required to avoid mixing up demands for specific data generated by means of adequate testing methods with the need to agree on criteria about how to interpret and categorize the test results within a specific regulatory framework.