My dad, an elder statesman of the entertainment industry, in the early ’80s

My father looked gaunt, tired. “Want me to help you to bed, Pop? Maybe you can catch a General Hospital rerun,” I said.

“I loved being on that show,” Pop whispered. He was falling fast asleep—until Altovise’s dogs came flying out of the house, jumped all over him, and got tangled in his medical tubes.

Pop was livid, “I’m a superstar, you f’in dogs! See, Trace, no one pays me any attention!” We both laughed. “Don’t make me laugh, Trace Face!” I called the strong and loving Lessie Lee to help me with the dogs and to take Pop in.

“Pop, remember when you won that Daytime Emmy Award for One Life to Live? [In which he had a recurring role.],” I said as we climbed my father and his IV up to his bedroom.

“I was nominated, never won, that was 1980. But I loved that show, too. Also nominated but never won for The Cosby Show in 1987,” Pop said as we tucked him into bed and turned on the television.

Dad, Princess Grace, and Cary Grant in 1971

My father loved game shows, too. He appeared on Family Feud in 1979 on ABC. He made a cameo on Card Sharks in 1981 on NBC. He and Altovise also appeared as panelists on Tattletales in the 1970s.

Dad, Liza, and Frank doing promo for their “comeback” concert, 1989

Performing with two of his favorite people, Frank Sinatra and Liza Minnelli, in 1989

In the 1980s, Pop performed in the Cannonball Run movies and continued his stage and film work. But after his hip surgery in the late 1980s, my father started to slow down. He was last seen onstage with Uncle Frank and Liza Minnelli in The Ultimate Event. In 1989, my father made his final film, Tap, which was a tribute to the legends of the tap dancing era.

I sat with my father as he fell asleep with the television on full blast. I watched him sleep and thought about all the wonderful trips we had gone on together after his divorce from my mother. Monaco, in the south of France, was the most memorable.

Monaco was the most beautiful place my husband and I had ever seen. Pop’s rules were simple: “You and Guy get here, and I will take care of everything else.” We happily agreed.

Upon arrival we were whisked to Monte Carlo through a tiny winding road of countryside that unfolded into one word: stunning. In the Principality of Monaco, the houses were small yet grand, the Côte d’Azur spectacular and, of course, the Palace. It didn’t seem quite real. Someone lives there? Holy cow!

We arrived at the Hôtel de Paris. I had stayed in some ritzy hotels but this one took the cake. The awe-inspiring lobby with crystal chandeliers and marble colonnades spoke of majestic sovereignty.

Cannonball Run II: Burt Reynolds, Dean Martin, Shirley MacLaine, Dad, and Frank Sinatra

Our room overlooked the plaza with a panoramic view of the Casino de Monte-Carlo. The Casino was designed by Charles Garnier, the architect of the Paris Opera House with beautiful frescoes and stained-glass windows. The Casino de Monte-Carlo was a far cry from the “anything goes” Las Vegas casinos. We would sit on the balcony and watch people come and go night after night, dressed to the nines.

Dad’s suite at the Hôtel de Paris, oh my gosh! It overlooked the entire French Riviera and the Prince’s palace. Breathtaking. We sat out on the balcony for hours chatting away amidst the royal spirit, glitz, and glamour that was Monaco.

Dad would throw out his infamous joke, “Do you know why I stay in this beautiful hotel?” “No, Pop,” I would reply. “Because I can,” Pop would say on key. We fell out laughing each and every time. But there was power behind his laugh. Never far from my father’s mind was the fact that there was a time when he couldn’t stay in beautiful hotels. Not just because of money, but because of the color of his skin. I think Pop always threw out his joke as a way of giving thanks to God.

Dad and Bruce Forsyth got together for an hour-long television special in 1980. Forsyth later said, “The best TV show I ever did was with Sammy Davis, Jr. I played for him when he sang, he played for me when I sang, and when people come to visit now and I show them the tape, it still stands up as a good show.”

I thought this was one of Pop’s funniest TV appearances—on The Jeffersons (with Isabel Sanford) in 1984.

Dad performed in Monaco and brought down the house. We were invited to the palace for dinner after the show. Wow, you cannot overdress for a dinner at the palace. It was about two in the morning, I think. Tiny tealight candles lit the path we strolled down. We dined outside, French Riviera style with Prince Rainier, Princess Caroline, Lynn Wyatt, a socialite from Texas, and other notable guests.

I sat next to Princess Caroline. I still struggle to describe my awe. I say it to this day—she was the most beautiful woman I have ever seen—her skin, her eyes, just striking. When I saw Princess Caroline, I thought, there are women and there are ladies. She was a lady in the true definition of the word.

Princess Caroline spoke perfect French and English, and who knows how many other languages. She was so composed at the table, such a fine hostess, made each guest feel special, like she had known us for years. Princess Caroline had a way of involving her guests in conversation that was beyond skilled; it was a true talent.

She asked me, “You and your husband have been together a long time. Are you thinking of children?” I stammered. How do you reply to a princess? Umm, oh don’t say umm, I thought. She sensed me lost in her charming spell, and gracefully broke in, “There is never a perfect time for children—just have them, treasure them.” All I could think of was, okay, Princess, yes Princess, so I nodded politely.

Another memorable trip I took with my father and my husband was to the White House in 1987. My father was the recipient of a Kennedy Center Honor. At the ceremony he would be honored by his closest friends, including Lucille Ball, who had come to the house over the years for my father’s home-cooked gourmet meals.

Dad had slept at the White House previously, as a guest under former President Nixon. Pop has been credited by the Nixon administration for what is now a tradition, the POW dinner. In 1987, he headed back to the White House, as a guest of President Ronald Reagan and Vice President George H. W. Bush. The Kennedy Center Honors would be a three-day extravaganza. My father could not have been more proud.

We arrived in Washington aboard Bill Cosby’s Gulf Stream jet, the Camille, named after his wife. Mr. Cosby had loaned his jet to Dad for the occasion, staffed with a private chef. From Van Nuys, California, we flew to St. Louis, where my father had to perform, then on to D.C. We flew by the beautiful arch. When I told Pop I didn’t see it too well, he had the pilot circle again. Pretty cool.

In D.C., my father gave us our own limo. He wanted a driver to take us wherever we wanted to tour for the duration of the stay. The driver took my husband and me to the Ritz-Carlton hotel, where Kennedy Center honorees and other guests were gathered. You could not walk anywhere in the Ritz without bumping into someone famous—it was surreal. Soon it was time for the main event.

“Can’t be late,” Dad always said, “it’s bad form.” Driving up to the White House, we were nervous. The protocol alone scared us, not to mention the security and receiving line. There was a cocktail party for Dad and other Kennedy Center honorees in the East Room, including the great Bette Davis, who was so beautiful. My husband and I were the only ones that weren’t famous. The pristine food spread was incredible. The president and first lady greeted each honoree privately, in a separate room.

Dad returned to the cocktail party after the private greeting. He was having a great time when he noticed a group of black guys that were peering out of the kitchen. Next thing I know, Dad was gone. Later, we found him in the kitchen, with his bow tie loosened, hanging out with all the folks who had made the evening possible. What else would you expect from Sammy Davis, Jr.? It was a touching moment, but nothing out of the ordinary. It was just Pop.

The evening of the Kennedy Center Honors, my father was beaming. The room was electric. It was not lost on me that it was the “Kennedy” Center: named after the Kennedys, who hurt my father so deeply when he was not invited to the JFK inauguration celebration—after all his hard work performing for the campaign. Ironic, I thought.

One day, we were invited to the State Department for a seated dinner with George Pratt Shultz, former US Secretary of State under Reagan. We rode in separate limos from the Ritz-Carlton, and pulled up to what I would call Fort Knox security. Once cleared by security, we entered a huge but somehow intimate ballroom with Kennedy Center honorees and other invited guests.

Over dinner, George Shultz spoke about football, the history of the room, and told funny stories about other dinners that put the table guests at ease.

After the State Department dinner, we returned to the Ritz-Carlton. We had drinks at a big table with honorees and guests—everyone laughing and kicking off their shoes, talking about our three-day extravaganza. We went around the room, each of us saying what we were thankful for. No one wanted the evening to end. We returned home on Bill Cosby’s Camille. Washington, D.C., was sure a once-in-a-lifetime trip.

Back to the reality of sitting by Pop, reminiscing about our travels in my head, as he rested. I told him something like, “I love you, Pop, you are an icon. Your star shines bright on the Hollywood Walk of Fame!”

“Thanks, Trace Face. Just don’t let me die here.” Pop was referring to his legacy, and keeping it alive. His heavy eyelids closed for the night and I headed home.

Once in my own room, melancholy set in motion. I kept hearing my father’s voice, “Just don’t let me die here.” I closed the blinds to shut out the moonlight and surrendered myself to a state of darkness. Despite my resistance, reality was mounting, and I knew the end was near.

![]()

Out of nowhere, I found myself in my Nissan 240SX upside down in an embankment off Tierra Rejada Road, near Thousand Oaks, California. I woke up to someone banging on my window pane. I felt water on my face. Was it raining? Where was I? No, it was not raining; it was blood on my face and I was stuck upside down in my car, pregnant. Don’t let me die, I thought. Don’t let my baby die. Bad enough that Pop was dying.

I was driving home from a CSUN Alumni basketball game, listening to “Tears for Fears” on a cassette player, when a big old car on a two-lane road between Simi Valley and Moorpark came smack into my lane. It hit me head on, and I rolled into an embankment, flipping upside down. I was pulled out of the car. It had automatic shoulder restraint seat belts. Luckily, I had forgotten the manual lap belt around my belly, which saved my unborn child’s life.

A sheriff’s deputy radioed in that “we have a fatality.” Paramedics came to the scene. The deputy asked, “Who else was in the car with you?” I replied, “No one. Call my dad.” The police asked, “What’s his name?” I said, “Sammy Davis, Jr.” There was a moment of disbelief, and I said, “Yeah, that’s him.” I gave up the number. My father was panicked, naturally. I could only imagine Pop hearing the news with flashes of his own nearly fatal car accident that took his eye.

They told my father that they were taking me to Los Robles Hospital and Medical Center. Mom was in Lake Tahoe at the time. Someone phoned her as well. A stranger called my husband, Guy. By the time Guy arrived, there were fire trucks and police cars everywhere. He pushed through the crowd shouting, “That’s my wife! That’s my wife! She’s pregnant!”

My obstetrician, Dr. Karalla, had me stay in the hospital overnight to check on the baby, but I was lucky that other than some minor bruising, we had both survived the crash. I called my father from the hospital, “I can’t attend your sixtieth anniversary tribute or I might lose your grandchild, Pop.” I told him I was nervous about the baby.

His tribute was only a few days away, but Pop was just relieved that God had worked another miracle in his life and mine. He told me not to worry, that it was good to be nervous—it’s a sign that you are alive and well, he said.

He recalled a story when he starred at the Royal Albert Hall in London with his two closest friends, Frank Sinatra and Liza Minnelli. It was part of the European leg of “The Ultimate Event” tour. Pop said he was so nervous when he walked into this grand concert hall, it was such a big jump from the Pigalle in the ’60s. Dad said he was sweating so much, if he had a piece of soap he could wash his hands. But he remembered what Eddie Cantor once told him, “Son, the day you stop being nervous before you face an audience, get out of the business.” “So be nervous, Trace Face,” he said, “it will keep you on your toes with the doctors.”

Dad in one of his most unusual roles—in Alice in Wonderland, 1985. Natalie Gregory played Alice. He was game for anything!

With Sonia Braga in the 1988 movie Moon Over Parador

Dad was on the upswing despite the cancer ravaging his body. My father taped his sixtieth anniversary tribute before a live audience at the Shrine Auditorium in Hollywood, without me beside him. Dad’s lifelong friends paid tribute and celebrated his sixty years in show business. This heartfelt special in his honor aired in April 1990. The show won an Emmy and was my father’s last major public appearance.

The tribute included video clips of Pop in show business all the way back to his childhood in vaudeville. Live tributes were performed by celebrity entertainers like Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Bill Cosby, Clint Eastwood, George Bush, Ella Fitzgerald, Eddie Murphy, Quincy Jones, Liza Minnelli, Bob Hope, Shirley MacLaine, Goldie Hawn, Whitney Houston, Jesse Jackson, Michael Jackson, and so many more.

There was one particular moment when Gregory Hines finished a tap dancing number, jumped off the stage, and kissed my father’s shoes, that was very touching. Michael Jackson took the stage with a song he composed just for Pop, “You Were There.” It was a song about how my father broke down the walls of racism and opened the door for him and other young artists of color. The utmost respect for my father enthroned Michael’s face. The lyrics were so powerful; the song sung so deep from within Michael’s heart and soul, it made my father tear up in the audience. Pop and Michael were always close. Michael called him Mr. D and used to come by the house, go to the library, and borrow tapes of Pop’s shows. He told Pop in Monte Carlo in 1988, “Y’know, I stole some moves from you, the attitudes.”

My father and Gregory Hines in a publicity shot for Tap, 1989

This tribute could not have come at a more perfect time to lift my father’s spirits. By this time, Pop knew he didn’t have much time left, and to see his closest friends honor his long career was exactly what he needed to close the final chapter of his life.

I was planning to go visit Pop after my baby checkup on April 19, 1990. My son’s due date was April 10, so he was already nine days late. I went for my appointment and Dr. Karalla said, “Don’t go home.” He checked me into Tarzana Regional Medical Center where he would induce labor. My husband, Guy, was by my side the whole time. My mother came before I was given a C-section.

My son, Sam, was born the next day, on April 20, 1990. Not only had God blessed me with a beautiful son, but Pop fought the doctor’s odds, and my revelation had indeed come true. Pop was still alive to meet his only blood grandson, named in his honor.

As we waited for the guard to open the gate to my father’s home, reporters literally laid on my car, snapping pictures of my husband, myself, and our newborn. We ignored the press, and pulled into Pop’s driveway. We grabbed the baby seat with our newborn in it and headed into Pop’s house.

We entered from the side entrance since Altovise had been locked out of his 3,400-square-foot master wing. Pop never talked to her. He would just hand her money from time to time.

We went into my father’s office, where the crew was gathered: Shirley, David Steinberg (Pop’s publicist turned producer), security guards, and Lessie Lee running the house. Little Sammy was naturally the center of attention, and everyone circled around him and spoke of how beautiful he was.

Pop was prepared that we were coming, so he was out of bed, trachea tube in, medication flowing through his IV, sitting on a huge, cozy chair in his bedroom as we walked in.

I had never seen my father’s face so happy as I said, “Hi, Dad” and showed him baby Sammy, half bent over in pain from my C-section. He was elated with tears of happiness, the wonder of it all, that look of “Wow, this is my grandchild.” I got so lucky; I had a boy, named him Sammy, and I had him in time for Pop to meet him.

After Sammy’s birth, Pop slipped in and out of responsiveness; cancer, bit by bit, robbed him of his life. I remember one day when I was visiting, Pop was lucid enough to say to me, “Trace, I’m scared.” I looked at him with watery eyes and said, “Me, too, Pop.”

The next time, my husband and I were visiting, the nurse was changing Pop’s sheets. My husband held Pop like a baby, softly kissing his forehead. From that moment on, my father was our hero. In his deteriorating state, he was a distinguished man, the finest I had ever seen. He rendered himself even more worthy of our regard. Guy gently put Dad down on the bed, into fresh linens, carefully, very carefully as just a gentle rub on his skin was painful. Time passed and his condition grew worse. From some vegetative state of half memory, Pop could still feel pain, and would wince if he was touched. There was no coming back from this. By the next visit, Pop couldn’t speak at all. From his eyes, you could tell he wasn’t all together there anymore. Was he in a coma? I don’t know.

Liza Minnelli was one of the few friends on Pop’s “OKAY Guest List” that he would allow to see him in his current condition. My father and Liza had been close pals for years. The day she came to the house, she knew it was a final good-bye, that this was the last time she would see my father alive.

Liza had covered a show in Lake Tahoe for my father when he first got the sore throat that was later diagnosed as cancer. It was August of 1989. Little did I suspect that this would signal the beginning of the end of my father’s life. “I got a little tickle, Trace, not doing the show tonight. Wanna come up to the suite?” Pop said over the phone. I was on my way. Pop and I had reconnected, and become true pals at my bachelorette party in Vegas. My bachelorette party was filled with champagne, jokes, laughs, and lots of stories with my friend Julie Clark, the McGuire sisters, Pop, and Frank Sinatra. It could not have been more perfect. I treasure those moments every day.

I went to my father’s suite at Harrah’s in Lake Tahoe with my friend Diane. I asked Dad what was wrong. He said, “Just a sore throat, no biggie.” My father couldn’t do the show that night. So of course, who comes in early to cover? Good ole Liza. What a kind, gracious soul. She did the show in a sweater and jeans—her luggage hadn’t arrived yet.

By the time Liza was done, the entire audience was in her hand. They had come to see Dad, a line wrapping around the casino, but Liza had taken them over. The result was pure magic. I thought, That is why Liza is a star. Forget that she was the child of Hollywood royalty. A talent and personality all her own made her a star. At the end of the show, Liza announced that Dad was truly sorry for missing the performance. Liza was a class act all the way. She and my father were a bona fide force of professional habit, captivating audiences with a mere glance all over the world—and best buddies to boot.

I went home late that night to Mom’s house in Tahoe. Something was bugging me; I didn’t know what, but something was bothering me. I tried to shrug it off, but it lingered in the distance, I just couldn’t shake it. Pop said he was going to be fine. He had never lied to me, so why didn’t I believe him?

I knew something was off but found solace in knowing that he was going to get a checkup, just to make sure. He was a singer and a smoker. He had sore throats before. Trace, I said to myself, stop. Just stop. But it stuck with me, the frailty of his condition. I felt uneasy.

I was right to worry, I would later learn. There was a node, a little something. Not a big deal. “May have a little surgery,” Pop said on the phone. It came slamming into reality. I have to get to Pop. I have to look at him, face to face. I would know then. I got in my car and drove to him. There he was. Alone, not unusual, I thought, but then it hit me. No cigarettes, no ash tray, no nothing.

Dad in Tap, 1989

A tribute to the great musical numbers in films of the past, That’s Dancing!, 1985

Pop tried to cover, but I knew we were in for a fight. I wanted answers. For better or worse, I got them. The sore throat had turned into a node and the node into cancer. Could this really be happening to my father? What now? I thought. Dad started his radiation. He was tired but he was strong, and even maintained his sense of humor. He had developed a bright red area on his neck. It was well known that he loved his Strawberry Crush. He said the red spot on his neck was from drinking so much of it; it finally leaked out. I laughed, but there is was. Cancer.

Liza had been there from the start, from the sore throat in Lake Tahoe, and now she was doing the death march with us. As Liza headed up the stairs to Pop’s bedroom, she had to stop on the huge landing and sit on the couch. She was scared to go up. She wanted to know every detail about his condition. “Trace Face, how bad is it? What does he look like?”

One question after another I answered to soothe her nerves, but it was clear that her anticipation was worse than actually seeing Pop would be.

When Liza saw my father, she kissed him, told him she loved him, and left. As I walked her out, she said seeing Pop “was heavy.” My father’s state was weighing on us all, family and close friends.

About a month after little Sammy was born, I was in Dad’s bedroom. I kept remembering what my father had said a few months before: “I will live to see my grandson, and after that I have nothing left to live for.”

Dad and Liza Minnelli, 1990. He’s holding his American Dance Honor.

Pop arrived in style at the Royal Albert Hall for one of his final performances, in 1989.

I leaned down and whispered in his ear, “Dad, it’s okay if you have to die. It’s okay. It’ll be okay. I remember everything you said. And I’ll take care of it, I promise.” I was referring to keeping his legacy alive. “I love you, Popsicle.” I kissed my father on his forehead and held his hand. I could feel his thumb brush against mine, so I knew he heard me. He gave me three tiny little squeezes. It was noticeable and deliberate, not an instinct.

Since my father was a megastar, we’d grown used to the press swarming about, but the whole family had been taught a code when we were young by our mother. The code was, if anything was up, squeeze Mom or Dad’s hand three times. Pop was not able to say anything back, but he squeezed my hand three times. That was enough for me.

My father died the next morning in his home at 5:56 am, on May 16, 1990. He was sixty-four years old. His funeral was held at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California. Being Jewish, the family did not want a viewing. We knew Pop would never want one. We were overruled by Altovise, now his widow, who insisted on having a wake with an open casket.

I refused to go to the wake, but would attend the funeral. I sent my husband, Guy, to the wake. Guy told me a photographer was taking pictures of my father in his casket. Appalled, I reached out to Shirley, who asked David Steinberg to do something about it. David threatened the photographer—told him that Frank Sinatra was so angry he was planning to have a contract put out on his life—if he didn’t hand over the film. It wasn’t true, but the photographer surrendered the film.

My father was generous to a fault. He left the bulk of his money to Altovise and trusts for his children. There was also an auction where a pair of his tap shoes sold for $11,000 among other memorabilia. His entire estate, property, house, gun collection, art, and memorabilia valued between six and eight million dollars.

People from all over the world, of all races and religions, mourned Dad’s death. Fans celebrated his life as the heavyweight champion of the entertainment world. Thousands stood in the roadway from my father’s house to Forest Lawn Memorial Park, clapping, shouting, and tipping their hats as the hearse and our limo motorcade drove by. I noted one fan even shaved words into his hair: LUV YOU SAMMY. Lessie Lee rode in the motorcade of limos with us, in a hat with short veil, a pocketbook, and all the trimmings of Southern style respect.

Out in Las Vegas, the lights on the Strip were darkened for ten minutes in honor of Sammy Davis, Jr.—an event that had only happened before for the deaths of President John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. Performers, entertainers, celebrities, family, and close friends eulogized him. Publications, some of which had criticized my father during his career, published glowing obituaries. Ebony magazine would write a tribute to Dad that through living his life, “the entertainer wrote the Fourteenth Amendment of Show Business.” Given Dad’s legacies, Ebony continued on and I quote, “Sammy Davis, Jr. established racial and religious tolerance in the entertainment industry.”

Reverend Jesse Jackson held the funeral service at Forest Lawn. He spoke of Sammy Davis, Jr. and said: “In this one person, black and white, east and west, find common ground. In this one person, African Americans and Jews find common ground.” His tribute to my father warmed our hearts. He referred to my father as “Mr. Bojangles” and asked the crowd to stand as he played a recording of Pop singing the song. I cried until I had no more tears left in me.

My Dad left the world of show business bereft of a pioneer whose vast talent shined in the face of racial adversity and opened the door for so many upcoming artists of color. Sammy Davis, Jr. touched generations of performers—beyond color barriers—with his talent and determination.

To me, the greatest relief I felt when Dad died was that the satellite trucks and reporters that were staked outside of his house on the narrow Summit Drive would leave. They had come one by one like buzzards to a carcass. This was pre-Twitter and still the press knew everything.

Now it was over. The trucks were backing away and packing up. Reporters left. The circus was leaving town and that could only mean one thing. Dad really was dead. He was? Yes, he was. Throughout this last personal journey with my father, the doctors told me that he would not recover from cancer, but I never really believed it. He had triumphed over so much adversity in his life, surely he would beat this.

In a way I was angry. Even at my own father. A smoker, no—a lifetime smoker. It had killed him. I still couldn’t entirely accept it. One time I found myself driving up to his house on Summit out of mere habit, arrived at the gate, only to realize what I had done, and turned the car around. I fought with God in my car. Please, I begged God, give me one word, one sign, that would ease my fear of living without my father. I tried to fix my thoughts on the future, my beautiful newborn son, my husband, anything that would carry me across this bridge, over this terrifying abyss, to a place where thoughts were beautiful again.

I wanted to be smack in the middle of Pop’s lavish emerald gardens with pungent eucalyptus trees and a sparkling pool. I wanted to be in a tranquil oasis where I could drink in the air and extract words, memories, stories, laughter, anything that would make me smile. Then, it came to me. I thought of what my pop would say at one of his private parties: “Leave while you’re still interesting, baby.” Somehow, someway, I cracked a smile and made my peace with Pop’s death.

Today, it is twenty-four years since my father passed. I still struggle with his loss at times. I recently wrote a “Final Good-Bye” letter to Pop after visiting him at Forest Lawn cemetery:

Oh my gosh, how you are missed. So many things to talk about and so many things left to be said. You taught me not to worry if I was a round peg in a square hole. You taught me to make my own hole. Who cares, you said.

I wish you could see all my children, Pop. I have four now, two boys and two girls. Sammy named after you, Montana Rae, Chase, and Greer. Remember when you said you were going to be the best grandpa ever? They missed that. But not to worry, Pop, I teach my kids about you all the time, bet you know that right?

I didn’t always realize it but I was the luckiest little girl and I am so happy you are my father. Brought up by two parents who looked racism in the eye and laughed at it—who built a cocoon for us, taught us to love no matter what. I must keep the legacy of your talent, determination, generosity, and love alive. I’m working on a new book about you that I hope will do just that.

I gotta go now, Pop. You’re my hero.

I will talk to you tonight, forever, for always, for love.

—Me

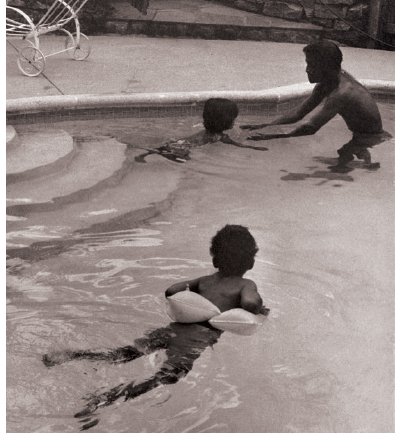

My brother Mark and I taking a swim with our father, 1966.