4

MURDER

June 25, 1906–July 15, 1906

“HELLO, LARRY,” WHITE EXCLAIMED, SEEING THE STAGE MANAGER Lionel Lawrence appear in front of the curtain. “How are all the girls?”1

Stanford White sat in his usual seat, at a small table near the front, waiting for the play to begin. The rooftop theater at Madison Square Garden was empty; but the audience would soon arrive, ascending in the elevator, occupying the seats at small tables in front of the stage and filling up the two benches that ran along each side.

The show that evening, Mamzelle Champagne, was a typical Broadway production, a musical comedy in two acts, with attractive girls and tuneful songs. It had already played in Atlantic City, and it was opening that night in New York to coincide with the start of the summer season. The reviews had all been tentative: the leading man, Harry Short, was an unknown with little Broadway experience, and the story was skeletal—a champagne bottle, transported from Paris, reveals its secrets—but it was opening night, and there was always a good audience at the first performance.2

Lionel Lawrence paused momentarily, stopping to exchange greetings. Lawrence had first met White several years before, when he had directed The Giddy Throng, a comic opera, at the New York Theatre. He liked White’s easy familiarity, his lack of pretension, and his jovial good humor, but he had little time now, thirty minutes before the start of the show, to stop and chat.

“Say, Larry,” White called out, indicating a young woman seated by the stage on the far side of the theater, “who is the little peach over there? I want to meet her.”

Lawrence recognized one of his actresses, Maude Fulton, a twenty-five-year-old making her Broadway debut.

“Some other time,” Lawrence answered. “I’ll make you acquainted, old man, some other time…. I can’t introduce you tonight,” he pleaded. “This is a first night and I have not a minute.”

“All right, Larry,” White replied cheerfully, “but bear in mind that I mean it, and I’ll keep you to your promise…. I like the looks of that girl and want to meet her.”3

White seemed carefree, apparently intent on enjoying the play. But his demeanor masked an anxiety over his financial troubles. His debts had accumulated gradually, silently multiplying over the years until they had reached almost a million dollars. Two acquaintances, Alfred Vanderbilt and J. Pierpont Morgan, had lent him large sums of money, but there was little chance that he would be able to repay his creditors. His partners, Charles McKim and William Rutherford Mead, had tolerated his extravagance for many years, but now their generosity had run its course. They had voted to end the terms of his association with the firm, removing him as a partner and insisting that he work as a salaried employee.4

It was a bitter irony that his connection to Madison Square Garden had proved financially ruinous. White had invested heavily in the project, and he was now a director and principal stockholder in the company that owned the building. But the mortgage had always been onerous; it had been a constant struggle to obtain bookings, and Madison Square Garden had rarely turned a profit. The main arena attracted shows of every description—bicycle races, horse shows, military parades, prizefights, political rallies, religious revivals—but the maintenance and operating costs always outran the receipts. Neither the restaurant on the first floor nor the concert hall above attracted sufficient customers, and only the interior theater had ever been profitable. And Madison Square was no longer a residential neighborhood—commercial office buildings had replaced the brownstones that previously lined its streets—and the theater district had moved uptown to Times Square. The land on which Madison Square Garden stood—an entire block between Madison Avenue and Fourth Avenue—had become increasingly valuable as the area changed, and the property taxes on the building had increased accordingly.5

One year before, White had reluctantly reconciled himself to selling part of his art collection to settle his debts. He had stored some of his most valuable artworks—sixteenth-century Italian tapestries, antique furniture, several seventeenth-century Flemish paintings, some statuary and decorative ironwork—in a warehouse on Thirtieth Street in preparation for the sale of the collection at auction. But disaster had struck: on February 13, 1905, fire broke out in a nearby printing shop; a northwesterly wind fanned the flames, and the blaze spread to the storage rooms, destroying White’s collection. There had been a heavy snowfall the previous night; the streets were not yet clear, and the fire trucks were unable to make their way in time. Stanford White had been too distraught to speak to the newspapers about the catastrophe—he had not insured the collection—but a close friend, Thomas Clarke, had claimed that the loss would be severe.6

White’s financial distress had gone hand in hand with a general decline in his health. He was now fifty-two; his hair had almost turned white, and he had recently gained a great deal of weight. Even the slightest exertion, merely walking up a flight of stairs, was sufficient to leave him short of breath. He had a recurrent pain on his right side, just above the rib cage, and all his joints seemed to ache in the most alarming manner.7

And finally, there was the wretched business with Harry Thaw. This irritating young man, the husband of Evelyn Nesbit, had long had an intense dislike of him and had recently hired private detectives to follow him around New York, all in the belief that he, White, was engaged in some nefarious activity. It was unsettling, even alarming, to know that Thaw’s detectives were shadowing him; but what could he do about it? His friends had advised him to be on his guard—Thaw was mentally unstable—but Stanford White disregarded their warnings. Harry Thaw had a reputation for assaulting young girls who had few means of defending themselves; but Thaw was otherwise a coward who would not dare attack one of New York’s most prominent citizens. He, Stanford White, had the resources and the determination to press charges if Thaw was so foolish as to assault him.8

Evelyn Nesbit watched absent-mindedly as the waiters moved about Café Martin taking orders. She had little appetite that evening and she played with the food on her plate, taking an occasional bite, listening as Harry and his two companions continued to talk among themselves. Truxtun Beale was telling them about his recent adventure in San Francisco. She glanced at her husband, directly opposite, as Harry interrupted to ask Beale about the shooting. Thomas McCaleb sat on her left, saying nothing, watching Beale impassively, his face expressionless, as Beale described how he had shot his victim.9

It had begun when a newspaper editor, Frederick Marriott, insulted Beale’s wife in one of his columns. Beale had called on Marriott at his home, demanding an apology. Both men had drawn their guns: Beale had emerged unscathed, but Marriott was badly hurt. The jury at Beale’s trial acquitted him of assault, accepting his defense that he had acted to safeguard the honor of his wife.10

Harry signaled to the maître d’hôtel that he was ready to pay the bill, remarking only that Beale had been very fortunate. It might have ended badly, he added, if the jury had taken a different view of the matter.

Evelyn Nesbit and Harry Thaw dined with friends at Café Martin on June 25, 1906, before walking across Madison Square to a performance of Mamzelle Champagne at Madison Square Garden. Café Martin, one of the most fashionable restaurants in Manhattan, opened in this location in 1901 after the previous tenant, Delmonico’s, moved uptown in 1899. (Library of Congress, LC-D401-70801)

He had bought tickets for Mamzelle Champagne, a musical comedy opening that night, and the four of them left the restaurant by the exit on Fifth Avenue, crossing to the park opposite. Madison Square Garden stood before them, on the northeast corner of Madison Square, its vast bulk dominating the square, its tower, illuminated by arc lights, stretching skyward. It had been an unusually mild day—there had been no hint of the sticky humidity that typically gripped New York during the summer months—and the sun had already started to sink below the horizon. The golden rays of the sunset flooded the park, falling directly onto the front of Madison Square Garden. The pale-yellow brickwork and white terracotta reflected the sunlight with an intense gleam, and in the center of the main façade, high above the street below, the purple-pink decoration surrounding the Palladian window had become incandescent. Everyone could agree that Madison Square Garden was the most beautiful building in New York, an anomaly in a city so thoroughly devoted to business and commerce.

They made their way across the park, passing a statue of Admiral David Farragut on their left, leaving the park at the northeast corner, at the intersection of Madison Avenue and Twenty-sixth Street. An elevator took them from the side entrance of Madison Square Garden to the rooftop. The play was already in progress and the theater was almost full—only a few places were still unoccupied—and they threaded their way through the maze of small tables, eventually reaching their seats.

Every producer of a musical hoped to repeat the success that Florodora had experienced a few years before. Harry Pincus, the producer of Mamzelle Champagne, had employed the same ingredients—catchy tunes, beautiful girls, dramatic scenes—but the magic that had worked so well for Florodora was missing from Mamzelle Champagne. The audience was already slightly restless, fretful that the play seemed so unexpectedly dreary. Harry Thaw quickly became impatient, irritated that he had brought his friends to see such a dull play. He found it impossible to sit still and he excused himself, whispering a few words to his companions before making his way to the south side of the roof, adjacent to Twenty-sixth Street.

An acquaintance, J. Clinch Smith, was sitting alone by the balustrade, and Thaw, seeing an empty chair, sat down next to his friend. Smith had studied law at Columbia University, but his inheritance allowed him to live as a man of leisure, sailing his yacht on Long Island Sound and riding his thoroughbreds on his country estate.

“How do you like the play?” Thaw began.

It was terribly slow, Smith replied; it surprised him that the theater had chosen Mamzelle Champagne to open its summer season.

Thaw nodded his agreement, saying only that it might be a success nevertheless; it was always difficult to predict the fate of a musical revue.

“What are you doing in Wall Street nowadays?” he asked. There was not much more, he felt, that either of them could say about the play.

“I haven’t bought any stocks in some time,” Smith replied. “Do you know anything?” he added.

The best investment anyone could make, Thaw replied, would be Amalgamated Copper. The company controlled many of the most important mines in Montana and was able to keep the price of copper artificially high. There was tremendous demand for the metal on account of the mania for electrification; electricity was the future, and copper was necessary for its success. Steel would also be a good investment: the United States Steel Company was one of the most profitable businesses in the country. “In fact,” Thaw advised, “if I had any money to invest I would put it all in steels and coppers, especially the copper.”11

Neither man was now paying much attention to the actors on the stage. They continued to chat, their voices hushed, talking quietly so as to avoid giving annoyance to their neighbors. Thaw was intrigued to discover that Smith planned to sail to Europe later that week, and the two men compared notes on passenger liners.

It was astonishing, Thaw remarked, how quickly a ship could cross the Atlantic these days. He was leaving with his wife on the SS Amerika on Wednesday, and it would take them less than a week to reach Germany. It was a new ship, built the previous year for the Hamburg America Line, and he was looking forward to the journey.

“Do you know the Amerika?” he asked.

“Yes,” Smith replied. “I only came out on her a few months ago.” It was a beautiful ship, lavishly decorated in the first-class section, but the suites were very expensive.

“It is a ridiculous thing,” Thaw agreed. “They charge for them $900.”

“What do you want so much room for? There is nobody but yourself and your wife.”

“Yes,” Thaw answered. “I know that, but when I go to Europe I want to have my meals served in my own private apartment, and that necessitates more room.”

He glanced out across the theater, scanning the audience, and he noticed Evelyn trying to catch his eye, beckoning him to return to his seat.

“Excuse me,” he said, turning to Smith, “I am going down this way.”12

Clinch Smith watched as Thaw made his way across the roof, walking along the side aisle and then threading a path through the maze of small tables. Evelyn Nesbit whispered some words to her husband, motioning to the empty seat by her side, and Harry Thaw sat down to watch the remainder of the play.

But Evelyn Nesbit also was impatient that Mamzelle Champagne was so dreary. She could not bear to sit still, to remain any longer in the theater. The play had not yet ended, but they started to leave, Evelyn and Thomas McCaleb in front, Harry Thaw and Truxtun Beale following.

Evelyn glanced behind her as they approached the elevator, looking to say some words to her husband, but he had disappeared. What had happened to Harry? How could he suddenly vanish? She looked around the roof, searching for him, thinking that perhaps he had returned to his seat to retrieve something. Where was he?

She was surprised to see, in the distance, directly in front of the stage, Stanford White sitting to one side, close to the balustrade, watching the play. He slouched in his seat, his right arm by his side, his left arm on the back of a neighboring chair. Suddenly she saw Harry, standing at the front of the theater, his right arm extended forward, his gun pointed directly at White.

At that moment Stanford White also noticed Thaw standing before him. White stiffened in his chair and started to rise to his feet; but it was too late. The first bullet entered White’s shoulder, tearing at his flesh and splintering the bone. White slumped backward, sending his wineglass crashing to the floor, and a second bullet hit him in the face, directly beneath his left eye. Thaw fired again and the third bullet hit White in the mouth, smashing his front teeth.13

Stanford White died instantly, his body falling to the ground face forward, a thin rivulet of blood trickling outward from his head and spreading slowly across the floor. Harry Thaw stood motionless, staring impassively at his victim, his gun still in his hand.14

Two of the actors on the stage had engaged in a duel only moments before, and nearby spectators, those seated close to the stage, believed that the shooting of Stanford White was part of the play. But Lionel Lawrence, watching from the wings, had witnessed the murder and already realized that it might precipitate a general panic among the audience. The chorus girls onstage had seen the shooting also, and they stopped singing, their voices trailing away in their bewilderment.

“Sing, girls, sing!” Lawrence called to the chorus girls, “for God’s sake, sing! Don’t stop!”

The orchestra had stopped playing, the musicians still staring at the spot where White’s body lay motionless, the entire ensemble paralyzed by confusion and fear. “Keep the music going!” Lawrence cried, urging the orchestra to continue, hoping to reassure the audience and prevent a panic.15

Harry Thaw, seemingly oblivious to the commotion, raised his right arm above his head, holding the gun by the barrel as if to indicate to the audience that he intended no further harm. He now started to walk slowly down the center aisle, toward the rear of the theater, and as he advanced, the spectators started to rise to their feet, craning their necks to get a better view and to discover the cause of the disturbance.

Lionel Lawrence stepped from the wings, striding to the front of the stage, holding his arms in front of him with a gesture meant to reassure the audience that there was no cause for alarm. “A most unfortunate accident has happened!” Lawrence called out from the stage. “The management regrets to ask that the audience leave at once, in an orderly manner. There is no danger—only an accident that will prevent a continuance of the performance.”16

Paul Brudi, the duty fireman, was the first person to reach Thaw, approaching him from behind and taking the gun, a blue-steel .22-caliber pistol, from his hand. Warner Paxton, a member of the audience, also came up behind Thaw, and both men, Brudi on the left, Paxton on the right, held Thaw, escorting him slowly down the center aisle toward the elevator at the rear of the theater.

There was no resistance, no attempt to escape on the part of Thaw. He had willingly given up his gun, and as he walked with his captors toward the exit, he started to speak, telling them why he had shot Stanford White.

“I did it,” Thaw explained, turning to address Brudi, “because he ruined my wife.”17

Neither Brudi nor Paxton gave him any response. Thaw continued to talk, speaking first to one man and then to the other, but they ignored him, tightly gripping his wrists as they slowly advanced along the center aisle toward the elevator.

Already they had arrived at the rear of the theater. Evelyn Nesbit, standing by the elevator doors, an anguished expression on her face, reached out for her husband, as if to embrace him.

“My God, Harry,” she cried. “What have you done? What have you done? My God, Harry, you’ve killed him.”

Thomas McCaleb had remained at Evelyn’s side. He stepped forward as she spoke, resting his hand on her arm as if to comfort her.

“God, Harry,” he exclaimed, “you must have been crazy.”

But Thaw, a slight smile on his face, seemed indifferent to their anguish. He glanced first at McCaleb, then at Evelyn, as his captors paused before the elevator doors, waiting to descend to the street. “He ruined your life, dear,” he said, speaking to his wife in a matter-of-fact way. “That’s why I did it.”18

Patrick Debs, the policeman on duty at Madison Square Garden, took Thaw into custody, walking with him toward the station house on Thirtieth Street. The prisoner seemed surprisingly acquiescent in his arrest, and the two men walked side by side along Madison Avenue. Debs was curious that Thaw should be so calm. He asked his prisoner if it was true that he had just killed Stanford White.

“He deserved it,” Thaw replied, speaking without rancor. “He deserved everything he could get. He ruined a girl and then deserted her.”

Why, Thaw asked, were they walking along Madison Avenue? Where were they going?

The police station was located a few blocks uptown, Debs replied, on Thirtieth Street, and he was taking Thaw to be booked. He, Thaw, would spend the night at the station house, and in the morning the magistrate would remand him into custody.19

It was not easy for Thaw to reconcile himself to his changed circumstances—his prison cell was cold and dark; his cot was uncomfortable; the clamor of the other prisoners kept him awake—and he passed a restless night. The next morning the police inspector, Max Schmittberger, took charge of the prisoner, ordering his transfer to headquarters on Mott Street. He would not grant Thaw any special privileges, Schmittberger declared, nothing to set him apart from the other prisoners. The police would escort Thaw to headquarters in the usual manner, chained and manacled, under armed guard, in a patrol wagon.20

A small group of journalists and spectators had already gathered at police headquarters to await Thaw’s arrival. The guard escorted Thaw past the expectant crowd into the Mott Street building to be photographed. It was customary to identify prisoners by the Bertillon system of measurement, and Thaw cheerfully cooperated, allowing his captors to measure his head and fingers, to determine his height and weight, and to record the color of his eyes.

There was a pleasing novelty about the experience that Thaw had not anticipated. The police headquarters building was located halfway down Mott Street, in the center of the Italian immigrant neighborhood, and even at ten o’clock in the morning the market stalls were busy, each proprietor competing with his neighbor for the attention of passers-by. Peddlers and pushcarts moved up and down the street, challenging knots of pedestrians for the right-of-way, while hordes of ragamuffin boys and girls, intent on mischief, ran in and out of the doors of the tenement houses. Inside police headquarters, a motley collection of pickpockets, cardsharps, prostitutes, swindlers, and gangsters waited, together with Harry Thaw, to be photographed and measured. It was a world apart, as different from Madison Square and Fifth Avenue as one could possibly imagine, and Thaw experienced its novelty as both exhilarating and exciting.

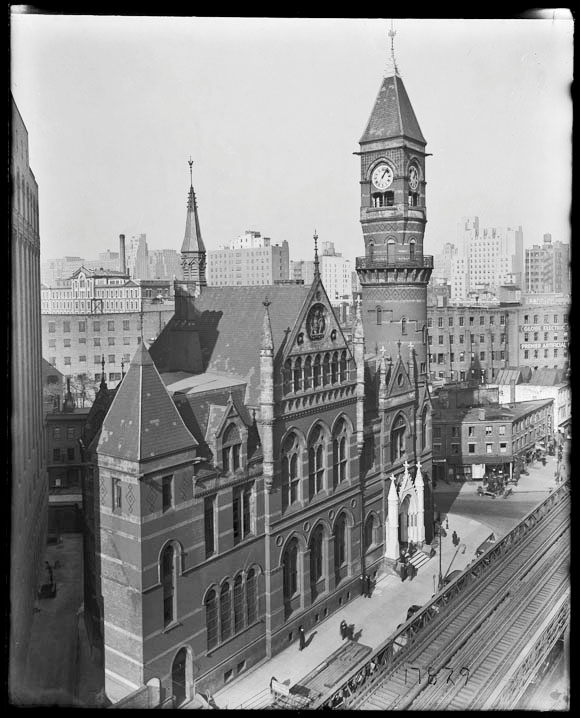

Thaw and his police entourage traveled next to Tenth Street, to the Jefferson Market Courthouse, a distinctive redbrick building in the Victorian Gothic style. The magistrate, Peter Barlow, remanded Thaw into the custody of the coroner until the completion of the inquest into Stanford White’s death.21

The Criminal Courts Building, a massive granite structure facing Centre Street, was the penultimate destination on Harry Thaw’s itinerary that day. Thaw’s attorneys, Daniel O’Reilly and Frederick Delafield, had already arrived at the courthouse, and Robert Turnbull, an assistant district attorney, was also present. Patrick Debs, the policeman who had taken Thaw into custody, presented an affidavit with the details of the arrest, and the coroner, Peter Dooley, committed Harry Thaw to the city prison.

Evelyn Nesbit called on her husband the next day. The prison, designed, incongruously, in the style of a French château, was an attractive building that provided no external sign of the cramped conditions within. Its location, between Centre and Lafayette Streets, had been the site of the original prison, nicknamed the Tombs on account of its resemblance to a mausoleum. In 1902 the city had condemned the Tombs as inadequate and unsanitary and had built a second prison, also called the Tombs, on the same site. The new prison, an eight-story behemoth in gray-white limestone, with a steeply pitched roof and two conical towers, stood directly south of the Criminal Courts Building. Franklin Street separated the prison from the courthouse, but an enclosed passageway, four stories above street level, connected the two buildings. The Tombs typically held only those prisoners awaiting trial, and each morning around eight o’clock, the guards began escorting individual prisoners across the bridge that led to the courthouse for the disposition of their cases.22

Harry Thaw was held in the city prison, nicknamed the Tombs, from June 1906 to February 1908. The Tombs, built in 1902, faced Centre Street, immediately next to the Criminal Courts Building. The bridge over Franklin Street, on the right of the photograph, allowed the guards to escort prisoners securely to the adjacent courthouse. (New York City Municipal Archives, mac_1926)

Evelyn Nesbit, accompanied by Harry’s younger brother Josiah Thaw, arrived at the prison at midday. The warden, Billy Flynn, escorted his visitors to the second tier, to the cells that housed those prisoners accused of homicide. Harry appeared remarkably cheerful, greeting his wife with a kiss, chatting amicably with his brother, and inquiring after his mother and sisters. It was inconvenient, he told Evelyn, that he must spend some time in the Tombs, but his imprisonment would not last long. Earlier that morning he had again met with his attorney Frederick Delafield, and he had learned that Black, Olcott, Gruber & Bonynge, a prominent New York criminal law firm, had agreed to join the defense. It was unfortunate, of course, that they could not now travel to Europe that summer; but it was necessary only to be patient to be assured of the right result.23

Evelyn Nesbit returned to Centre Street the following day, to the Criminal Courts Building, in response to a subpoena to appear before the grand jury. She had reluctantly agreed to appear in the jury room, but she would not answer questions, even if she risked being held in contempt of court. “I must respectfully decline,” she began, speaking directly to the members of the grand jury, “to answer the questions you intend to ask me…. I might say something that would harm my husband, and I think a wife should do all she can to help her husband and nothing to hurt him. Therefore I beg of you all, not to insist upon putting these questions to me, because if you do, I will have to decline to answer.”24

It was a brave response that won the approval of the jury. The foreman, Henry Smith, whispered some words to his colleagues and then informed the witness that there would be no further questions. Other witnesses did testify to the shooting, and, later that afternoon, the grand jury returned an indictment for murder in the first degree against Harry Thaw.25

He entered his plea the next day. The clerk of the court addressed Thaw in the customary manner, asking for his plea in response to the indictment, and Thaw, without pausing to consult his lawyers, replied that he was not guilty.26

That week, while Harry Thaw prepared for his upcoming trial, Bessie White organized the funeral of her husband. The body of Stanford White had lain, since the murder, in the drawing room of the family’s Manhattan residence, a four-story town house near Gramercy Park. On Thursday, June 28, the undertaker brought the body to the Thirty-fourth Street ferry for the journey across the East River to Long Island City, where a special train waited to carry the casket to St. James, the village adjacent to the family estate on Long Island. Several dozen mourners, friends of Stanford White, accompanied the casket on the journey, each mourner caught in a shared sense of dismay that White had died such a violent death, so suddenly and unexpectedly.27

The service was brief, devoid of the panegyrics that might normally have accompanied the burial of so remarkable an individual as Stanford White. William Holden, the pastor of St. James Episcopal Church, recited a psalm and the choir sang a hymn. Leighton Parks, the rector of St. Bartholomew’s, an Episcopal church on Madison Avenue, next pronounced a benediction. Bessie White and her son, Lawrence, then led the procession from the church to the nearby cemetery, and after the pastor had spoken some brief remarks, the gravediggers began to cover the casket with earth. Charles McKim and William Rutherford Mead both lingered to console the widow, promising Bessie White that they would settle any business matters that remained.28

It had been a modest ceremony, without any pomp or ostentation, in a Long Island village, far from the hustle and bustle of Manhattan. The funeral had originally been intended for St. Bartholomew’s, but already too much controversy had accumulated around the memory of Stanford White for the congregation to consent to the service.29

Stanford White had been dead only three days, but the newspapers had already passed judgment, condemning him as a libertine who used his power and influence to lure unsuspecting girls to his apartment to rape them. The cause of the murder was, according to the newspaper accounts, the rape of Evelyn Nesbit as a young girl several years earlier. Several women, actresses on the Broadway stage, had reportedly corroborated this narrative, volunteering to the defense lawyers that White had raped them also.30

Anthony Comstock claimed that his organization, the Society for the Suppression of Vice, had uncovered evidence that coteries of wealthy men frequently sponsored orgies in which young girls, recruited from the tenements, were the victims. James Lawrence Breese, the society photographer, was the leader of one group of men, nicknamed the Carbonites, who met for riotous dinners in Breese’s studio on Sixteenth Street. A second clique, according to Comstock, lured actresses and chorus girls, some as young as fifteen, to an apartment owned by Charles Dana Gibson on Thirty-fifth Street. “I will drive every moral pervert out of New York,” Comstock declared. “The investigation must go on now to the bitter end, without fear or favor, no matter how rich or how prominent or how brilliant the perverts may be…. Many a man who has been generally held in the highest esteem must be tumbled into the mire, where he belongs.”31

The prosecution of wealthy pedophiles was long overdue, Comstock proclaimed. It was the evident reluctance of the district attorney to investigate Stanford White that had led to his murder. “Thaw’s act in slaying White,” Comstock stated, “was the indirect result of the refusal by the proper authorities to bring White to book.”32

Comstock’s accusations found a ready echo in denunciations from the pulpit. Stanford White had engaged in the most wicked crimes, using his association with the theater to rob young girls of their innocence, and White’s life, according to Madison Peters, a minister at the Church of the Epiphany, was a predictable consequence of the concentration of wealth, the corruption of morality, and the failure of the authorities to safeguard civic virtue. “These crimes, worse than murder,” Peters declared, “must be avenged. That there are men of large wealth in this city who have made it a business to degrade womanhood—backing plays and players and using art studios to procure poor young girls… is a new revelation to the public: a new story that wealth has turned its rotting force to the corruption of innocent girlhood, whose misfortune is their poverty.”33

Reuben Torrey, an evangelical preacher, was sanguine that the revelations about White would effect a reawakening. “Exposures of moral leprosy,” Torrey commented, “always do good…. The outraged public sense of purity and decency revolts and turns on these criminals and brings about moral regeneration…. No jury will be found to convict Thaw, in my opinion.” Thomas B. Gregory, a minister of the Universalist Church, agreed that, in a technical sense, Harry Thaw had indeed broken the law; but he had also fulfilled a higher law that transcended the formal statute. “When the libertine falls,” Gregory proclaimed, “every healthy instinct of humanity feels, and cannot help feeling, that it is only the natural finale.”34

Several of White’s closest friends had already vanished, leaving little trace of their whereabouts. Reporters from the city’s newspapers fanned out across New York, hunting for White’s accomplices, hoping to provide the accused men with an opportunity to rebut the charges. James Breese could not be found either at his Manhattan residence or at his favorite haunt, the Metropolitan Club. The antiques dealer Thomas Clarke did not return to the city after attending White’s funeral, and there was a suspicion that he had already left the United States for an extended stay in Europe. Robert Lewis Reid, an artist, had not been seen at his studio, and the caretaker could provide no further information.35

His many friends, some of whom had known White for decades, stayed silent, refusing any association with a man who had become a moral leper. Even Charles McKim, who had worked closely with White since the 1870s, refused to condemn the murder of his friend. “There is no statement to make,” McKim answered in response to a query from a reporter for the New York World. “There will be no information coming from us.”36

A few brave souls did resist the tide of public opinion, remarking on the contribution that White had made to architecture in the United States. The sculptor Augustus Lukeman noted the surprising reluctance of the architectural profession to pay tribute to the dead man. “No voice appears to be raised,” Lukeman said, “calling attention to the stupendous loss that has befallen the country in the death of Stanford White…. Mr. White was not only an artist, a great architect, if not the greatest of his age, but he had a generous spirit, which stimulated… the taste of the public to a higher standard of beauty.” John M. Carrère, one of the partners of Carrère & Hastings, the firm responsible for the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue, had worked as an apprentice for McKim, Mead & White, and he also mourned the death of White. “I have always looked up to him both as an architect and as a teacher. He was the foremost man of his profession,” Carrère told a reporter from the New York Times. “Speaking generally of his position among American architects I consider that he had no superior.”37

The emerging consensus that the authorities had been negligent in failing to apprehend such men as Stanford White both provoked the police to take more forceful action and emboldened such reform organizations as the Society for the Suppression of Vice in their campaign for moral purity. The arrest of Henry Alfred Short on July 1 for molesting young girls was one sign that the authorities looked to end the sexual exploitation of children. Short, a wealthy realtor and a member of the University Club, had lured Charlotte Fitzsimmons to his apartment with gifts of candy. He had repeatedly raped the fourteen-year-old, telling her that he would kill her if she told her parents; but the girl had eventually informed her father, and the police had raided Short’s apartment, finding a trove of pornographic photographs.38

Anthony Comstock applauded such initiatives but continued to urge his acolytes to take independent action to combat such social evils as prostitution and pornography. Nothing in this regard was more infuriating to the Society for the Suppression of Vice than the complicity of newspaper proprietors in promoting prostitution, and no one was more culpable than James Gordon Bennett Jr., the owner and publisher of the New York Herald. Hundreds of paid notices, offering various services, appeared in the Herald every day; these advertisements never explicitly mentioned sex, but their meaning was nevertheless obvious. Such notices promoted prostitution, Comstock asserted, yet Bennett had always denied any responsibility, claiming that it was impossible for the Herald to distinguish between advertisements that offered companionship and those that offered sex.39

But the campaign for moral purity would not be denied, and on July 7, Charles Wahle, a magistrate in the Seventh District Police Court, issued a summons against the New York Herald for printing obscene and lewd matter. Charles Grubb, a pastor of the Methodist Episcopal Church, had initiated the complaint, but it was equally a triumph for Comstock and the Society for the Suppression of Vice.40

The campaign for moral rectitude simultaneously denigrated Stanford White and exalted Harry Thaw. White had reportedly continued to pester Evelyn Nesbit after the rape, even attempting to resume their relationship after she had married Harry Thaw. Who would not, under such circumstances, act as Thaw had acted, to avenge the honor of his wife? The authorities had taken no action and had done nothing to stop White. Surely, many commentators argued, Thaw had been justified in shooting Stanford White.

William Olcott, an attorney in criminal law, a partner at Black, Olcott, Gruber & Bonynge, had first encountered Harry Thaw on June 27, and already, less than a week later, he was starting to regret his firm’s connection with the case. He had cautioned Thaw that he could avoid the electric chair only if he pleaded insanity; but the prisoner rejected his advice outright, saying that White’s assault on his wife had given him every justification for killing the architect. “No jury will convict me of any crime,” Thaw had explained, “when they hear the truth. I killed White because he ruined my wife. I am not crazy.”41

Olcott had suggested to Thaw that his attorneys petition the Court of General Sessions to appoint a lunacy commission—a panel of three experts—to determine Thaw’s mental condition. This commission could then recommend that the court commit the prisoner to an asylum. Thaw would remain in the asylum for a certain period, a few years, say, and could subsequently apply for his release on the supposition that he had regained his sanity. There would then be no necessity to endure the uncertainty of a trial, no need for an elaborate and expensive defense, and no danger that a jury would find Thaw guilty of murder.

But nothing could dislodge Thaw’s belief that he had acted rationally and justifiably in killing Stanford White. There was no reason, Thaw stated, why he should spend any time in an asylum; he refused to apply for a lunacy commission, as Olcott had suggested, or to file a plea of insanity at trial. There was, he declared, no need for him to meet with the psychiatrists whom Olcott had hired, and he would not tolerate any examination that might question his sanity. “I am the boss,” Thaw told Olcott, “and I won’t plead insanity. I’m no more crazy than you are.”42

It was in vain that Olcott argued for an insanity plea. Stanford White may have led a dissolute life, Olcott said, but there was no independent evidence, apart from Evelyn Nesbit’s testimony, that the rape had occurred, and there would necessarily be no possibility of presenting any corroborating testimony that would support her account. The alleged rape had taken place in 1901, shortly after Evelyn moved to New York, several months before she first met Harry, and four years before their marriage in 1905. Was it meaningful to claim, therefore, that the murder of White had occurred in defense of Evelyn Nesbit when the supposed rape had been committed several years before? Would it seem reasonable to a jury that Thaw found his justification in an act that had happened so long ago? Why would Harry Thaw have waited such a length of time before killing his rival?

Thaw was adamant, nevertheless, that his defense—the “unwritten law” that a husband could legitimately kill a man who had dishonored his wife—would persuade the jury to free him. He had done the world a great favor, he believed, by killing White. He would assuredly win his case. Such a defense, Olcott replied, might find favor in the southern states, in Georgia, say, or Alabama or Kentucky; but it would not work with a Manhattan jury. Jurors in New York were too sophisticated, too knowledgeable, to believe that a man could kill another man solely on account of some supposed wrong.

But such arguments counted for little when set against the tsunami of public opinion that congratulated Harry Thaw for his act of killing White. Every day, sackfuls of mail, from every part of the United States, arrived at the Tombs, each letter praising Thaw for his courage. Opinion polls in the New York newspapers were equally celebratory, an overwhelming majority of New Yorkers supporting the murder and predicting that the jury would acquit Thaw at his upcoming trial.43

It infuriated Thaw to learn that, despite his instructions, William Olcott continued to act as if he would present an insanity defense at the upcoming trial. Various newspaper accounts reported that Olcott, suspecting the existence of hereditary insanity in the Thaw family, had surreptitiously traveled to Philadelphia to interview staff at the Friends’ Asylum for the Insane. Harriet Thaw, a cousin, had resided at the asylum for several years, and it was reasonable to assume that Olcott hoped to present evidence of insanity among Harry Thaw’s relatives in order to win an acquittal.44

It was the final straw, an act of insubordination that Thaw would not tolerate, and on July 14 he informed Olcott that his firm’s services would no longer be required. He had hired Hartridge & Peabody to represent him, and he asked Olcott to send the papers on his case to Clifford Hartridge at his offices on Broadway.45

But that day, at the very moment when Thaw was dismissing his attorneys, his mother arrived back in New York on the SS Kaiserin Auguste Victoria. Mary Thaw had left the city three weeks before, sailing from New York on the SS Minneapolis. Only on her arrival in England did she learn that Harry had killed Stanford White, and almost immediately she booked her return passage to the United States, arriving back in the city on July 14.46

She called on Harry the next day. It would be folly, she told her son, to imagine that a jury would acquit him of murder solely because Stanford White had assaulted Evelyn Nesbit five years before. There would be too great a risk that the jury would vote to convict; it would be far better either to petition for a lunacy commission or to plead insanity at trial. But Harry remained maddeningly obstinate, refusing to hear his mother’s pleas, determined to state his case in court. “I am a sane man,” he patiently maintained, “and I will never consent to have these alienists construe my actions, my conversation and my physical being as those of an insane person. The unwritten law must be my defense. I killed White because I had to. Instead of being guilty of murder I should be looked upon as a benefactor to mankind.”47

Mary Thaw eventually acceded to her son’s wishes. There could be no insanity defense if Harry refused to allow the psychiatrists to examine him, and there appeared no possibility that his resolve would ever weaken. But Harry’s strategy would depend on a single witness—Evelyn Nesbit—whose testimony must persuade the jury that Stanford White had in fact drugged and raped her. No other person had witnessed the alleged rape, and no one could testify in support of Evelyn’s statements on the witness stand. There was no physical evidence to corroborate her story, and everything, therefore, would necessarily depend on the coherence of her account.48

But how would it be possible for a young woman, twenty-one years old, with no courtroom experience and no knowledge of the law, to withstand the pressure that the district attorney would inevitably bring to bear? She would be alone on the witness stand, testifying to events that had occurred several years previously, trying to recall details that might now be only vaguely remembered, and all the time, at every moment, the prosecution would be seeking to expose contradictions in her account, to catch her in a lie, and to reveal her testimony as false. William Travers Jerome, the district attorney, a shrewd, calculating prosecutor, a man with extensive experience in the city’s criminal justice system, would mercilessly interrogate her on cross-examination. It would be an unequal contest—Evelyn Nesbit would falter in her testimony—and everyone predicted that Harry would go to the electric chair.