The Four Stages of the Leading Meaningful Change Process

The Four Stages of the Leading Meaningful Change Process  The Four Stages of the Leading Meaningful Change Process

The Four Stages of the Leading Meaningful Change Process The field of change management has grown considerably over the past few decades. There are now many models that organizations can use to develop and guide their change journeys. Over the years, I have worked with the ExperienceChange model developed by Greg Warman and James Chisholm of ExperiencePoint. This model has seven steps designed to build a shared vision, commitment, and alignment among key stakeholders and engage others across the organization to support and implement change. The seven steps are:

The first three steps are designed to align the key stakeholders, while the next four are designed to engage the rest of the organization in the change process. This ExperienceChange model is very effective in illustrating the steps to develop and implement a change plan.

However, much like the ExperienceChange model, most change models that my clients have used over the years have focused solely on change management and did not incorporate into their processes the Use-of-Self or concepts of change leadership. Based on my own research and practice, I have therefore developed a different change model, the LMC Process, that includes all three elements—Use-of-Self, change leadership, and change management. All three elements are critical and featured in the LMC Process to help organizations follow a chronology of thinking and acting when undertaking transformation of any size.

In addition, the seven principles of the LMC Framework you just learned about guide a leader’s or a team’s Use-of-Self in leading, managing, and implementing the change effort. These principles strengthen the four-stage LMC Process that I have created to ensure that the entire model is grounded in the holistic precepts that contribute to making the change meaningful to all involved.

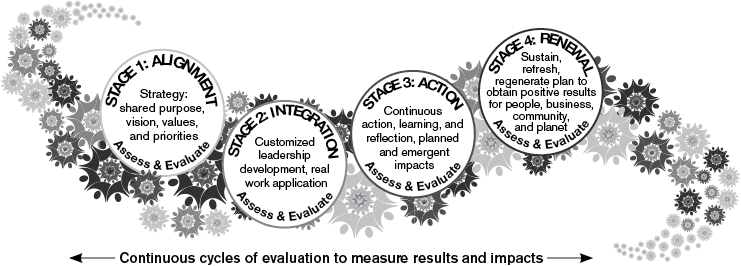

Figure 5 illustrates the four key stages in the LMC Process: alignment, integration, action, and renewal. These stages are constantly in play during the design, delivery, and evaluation of people’s experiences and the achievement of results throughout the change process. You may use this process for one project, or it can be scaled up or down, depending on the complexity of your work. Let’s walk through the stages one by one.

Focus: Planning and developing a shared purpose and alignment with vision, values, and strategic priorities

This first stage is focused on developing the plan to create alignment with the strategy, shared purpose, vision, values, and priorities. It requires the organization’s senior leaders and others to research and define the purpose of the change. They then need to ensure and articulate that the change or direction aligns with the organization’s overall purpose, vision, and values. Effectively, if a culture shift is to succeed, it must be aligned with the organizational purpose, vision, mission, and strategic priorities. The goal of this stage is to ensure change leaders at all levels understand their role in leading and managing the change journey and that it is in sync with the organization as a whole.

Depending on the complexity of the change project, the process is often best done by forming a design team composed of a cross-section of people who bring diverse thinking, experiences, and approaches into this preliminary planning work. The design team might include representatives with multidisciplinary or cross-functional expertise from the business and support functions such as human resources, organizational development, communications, continuous improvement, and/or process improvement. They may also be members of the governing board of your organization or people from outside, such as clients, partners, political stakeholders, members of the community, and external consultants. Combined, these people will offer diverse perspectives, insights, and ideas that will enhance your research and analysis and help you understand more fully the organizational culture, its challenges, and what is required for success in this change effort.

In addition to developing the plan and process, the design team’s mandate is also to align the program with the organization’s mission and strategy, as well as test the feasibility of the program’s design, content, delivery, and supports before, during, and after the program. By working together, the design team can facilitate faster and more efficient knowledge transfer and skill development, a shared mindset, and alignment, resulting in a more sustainable culture shift.

Here are questions for the design team or the leader to consider when working through this stage:

The alignment stage should not be taken lightly. Leaders and participants on the design team need to invest in a serious study of the organizational culture to understand how it evolved, what is considered sacred and must be kept, and what is open to change. Consider this stage as a project that can take months, a year, or even longer depending on the complexity of the change. Aligning an executive leadership team and relevant stakeholders to the point where they truly have a clear and shared understanding of the plan, the vision, the direction, and their roles and accountabilities can take more time and effort than you may imagine.

The Alignment Checklist (page 92) is a tool that lists the critical responsibilities at this stage. This worksheet can help ensure your planning is comprehensive and has accounted for the essential tasks that need to be accomplished in this phase.

Stage 1 Alignment Checklist

Check off the elements you have in place for this stage of alignment.

Focus: Application of learning and development

Leaders are often sent to “training” to learn new concepts and skills associated with the change plan, yet they are not supported to continue their development upon return to their workplace. They struggle to integrate their learning into their work and life. To ensure the sustainability of change, the plan and process must be designed to account for meaningful integration of learning and work, in real time. This usually requires customizing the program content and development process to ensure participants use their real work and life experiences as the basis for reflecting, experimenting, and applying their learning. If this is not done, there is a risk of additional stress and burnout from having to juggle unrealistic expectations, multiple priorities, and additional work.

Learning experiences are most valuable, meaningful, and relevant when they add value to the participant’s work and life. The key is to engage people and motivate them to master and integrate the new concepts, skills, and learning back into their real work and to teach, coach, and empower others to do the same.

Here are some questions to help you determine what you need to do to successfully complete the integration stage:

Once the change process begins, leaders, staff, and employees may need to adopt a new perspective, behaviors, and skills. However, initially people often resist change and may struggle with applying new learning to their real work and life. Despite retraining, they often revert to their old ways of thinking and doing their jobs. Customizing the content and tools so they have actual meaning and application in people’s real jobs is therefore essential. The key is to design the learning so people can use their real work and life experience as the basis for reflecting on, experimenting with, and applying the new skills. Working on real projects has been proven to be more effective than working on hypothetical research or academic case studies. Real projects stem from actual challenges that people are held accountable for and must act upon.

The choice of learning projects should be based on tangible needs that people have in their workplace. The projects should help people reflect on the tasks and decisions that they deal with given their span of control and influence. Through such projects, they can understand the purpose of the change and adapt to it voluntarily and willingly. It’s also important that the change projects be linked to the strategic priorities of the organization. This “use work, don’t make work” approach helps everyone engage meaningfully in the process and ensures that the work being done in a classroom setting or informal and social training can be applied and sustained between sessions and thus have real impact in the workplace.

To increase the probability of success and sustainability over the long term, I recommend that learning projects (which I also call “change challenges”) be assignments people can complete on their own, or as part of a project team, or with leaders who are attending the working sessions. The projects should be within the participants’ span of control or authority and supported by their immediate managers. Ideally, the projects should also be aligned with the department’s strategic goals and designed to support each individual’s personal learning objectives. In this way, people can take pride in what they have learned about the change and the role they play in contributing to it.

Here is how one senior leader in a mining organization developed a learning strategy to establish a culture of safety. This culture shift required changes in both mindset and behaviors of people working in the corporate offices and in the field. The company provided workshops and training for all employees and tracked how well they were doing using regular feedback they received from the teams. They also created a number of performance indicators that they tracked. They then communicated the results at regular team meetings. All meetings opened with “safety moments” that highlighted the new principles and best practices to follow, a story about incidents that occurred or were avoided, and lessons learned. This culture shift was significant for the organization. They were effective at integrating training with real work, which led to sustainable change over time.

Here is a brief look at the Change Leadership Challenge Exercise to help you integrate your development with your work. Completing this exercise at the beginning of your change, midway through, and at the end is a great way to reflect on and evaluate the culture shifts and effectiveness of your leadership and the plan. In the part 2 toolkit, you will find complete instructions for this exercise and an example of how one person completed it.

Here is a checklist to help you assess that all the elements for stage 2 are in place.

Stage 2 Integration Checklist

Check off the elements you have in place for this stage of integration.

Focus: A continuous and dynamic cycle of action, learning, and reflection about planned and emergent impacts

The essence of the change effort occurs in stage 3, where the action really begins to take place. The focus of this stage is to participate in a continuous, dynamic, and multifaceted cycle of learning, action, and reflection as you implement the plan and respond to the planned and emergent impacts along the way.

The action phase is not static. It must be done with an awareness that even the change can change. Any actions must remain open to adaptations as new information and feedback come in. The organizational environment is a living laboratory in which the processes of observing, reflecting, planning, acting, and evaluating are iterative, dynamic, and interactive. As soon as we inter-ACT with the system, we can expect a re-ACTION. This dynamic is always at play. At times our action may achieve our intentions, while at other times we may encounter unexpected reactions.

Either way, taking action propels us away from doing nothing to doing something. Even small progress allows us to gain confidence as we learn about ourselves and others, especially the impact the change may have on the larger system. Ultimately, taking action helps us make more informed decisions that lead to deeper and more impactful interventions on all levels.

In this stage, we especially need to notice and become aware of the impact our actions have on others. We can do this by walking in the shoes of others. Seeking to understand their world, we develop empathy and deepen our understanding of the shared values, norms, and cultural implications that are constantly at play when we interact with others. While moving forward with the change plans, a corollary goal is thus to ensure that people are intentional in their Use-of-Self; they need to be aware of the choices they make and the impact their actions have on others. In this way, people learn how to be more effective as leaders, observers, participants, and ultimately intervenors.

The typical change project or initiative usually has a beginning, middle, and end. However, we know that this is not how change happens. In reality, it is complex and can get messy. People go through their own personal experience of the change, layered by whatever else emerges in the process. Individually, as a team, and collectively, we need to pay attention and reflect on the impacts of the planned and emergent changes, and our actions and reactions to them. This rich learning will further inform our choices and actions. In addition to being leaders and implementers in the action phase, we need to be observers and intervenors throughout the process.

Here are some questions to help identify the emerging themes, patterns, and issues that may arise during the action phase. These questions can be asked at key milestones, checkpoints, and/or at the end of a project. You can also adapt these to use with teams.

And here are some questions to measure and evaluate the success of your efforts in this stage:

This stage of the LMC Process is also focused on measuring the impact of the leaders, teams, and collective actions on advancing the change initiative and desired results for the people involved and impacted, as well as for the business, community, and the planet. While I discuss this as a discrete element, as I emphasized earlier, evaluation and measurement are really part of an iterative and fluid process that takes place throughout the entire LMC Process, within each of the prior stages—alignment, integration, and action. It is also part of stage 4: renewal.

Here is a checklist to help you assess the work of the action stage.

Stage 3 Action Checklist

Check off the elements you have in place for this stage of action.

Focus: Evaluation of the overall change and planning for its sustainability

The renewal phase is an important part of the LMC Process. It is designed to conduct an overall evaluation of the change process. This evaluation should be done at critical milestones, at the completion of the project or process, and/or just before you begin the next phase of the work or change plan. Stage 4 focuses on reviewing and evaluating the overall strategy, results, accomplishments, and missteps to determine why and what worked well. What needs to be improved? What about the organizational culture, structures, processes, systems, changes, and insights need to be sustained or regenerated to ensure success in the long term or the next phase?

At this stage I often ask people, “Based on your experience leading this change, what advice would you give to a colleague about to embark on a similar journey?” Almost no one says that you need to pace yourself. This is a long game. Take care of yourself. Take time to reenergize and ensure you have balance. Pay attention to your personal and family well-being. I have seen a lot of people who were very passionate and worked extremely hard to lead meaningful change, yet by the end they were exhausted and had experienced personal illnesses, relationship breakups or divorces, and problems within their families. Those who did well had balance and paid attention to their personal goals and well-being throughout the process. They put in place supports that helped them, such as coaching, mentoring, and regular get-togethers with their peers and colleagues. They also established boundaries between work and family time, participated in regular exercise and fun activities that brought them joy and grounded them, and had healthy eating habits.

If leaders drive change too hard, they may influence an organizational culture that will be out of balance and result in high staff turnover. If this happens, you may need to rethink the pace and sustainability of the changes. Alternatively, you may have been very successful and can take time to renew the team and organization’s commitment to itself and the way forward.

Even if you’ve achieved success, it is important to reflect. Here are a few questions to help you reflect on the impacts of the changes and your actions:

The answers to these questions may reveal that the change effort is actually not fully done and that one or more of the stages in the four-stage LMC Process needs further attention, modification, and/or renewal.

The checklists for stages 1, 2, and 3 are effectively reminders to do an ongoing evaluation. Measuring the impacts at the individual, team, organizational, and community levels throughout your change process provides rich data, deeper insights, and often new strategies that can sustain the changes, leadership development, and culture shifts beyond your project, working sessions, and planned activities.

This checklist (page 107) can help you assess that you have all the elements necessary to evaluate the success of the change effort throughout the four stages of the process.

In part 2, you can complete an exercise called Evaluating and Sustaining Meaningful Change to see how well you are doing in each stage of the LMC Process and develop a plan for your next steps. There is also an exercise called Stakeholder Analysis that will help you evaluate where your stakeholders are in terms of their acceptance of the change plans. This exercise will also help you reflect on the technical, political, and symbolic strategies you need to employ to reduce any stakeholder resistance and respond to their concerns.

In the City of Ottawa case study in chapter 7, you will read about how the four-stage LMC Process was used to help the city’s senior leadership team design and implement a significant transformation affecting all city services by fostering a culture of One City, One Team.

Stage 4 Renewal Checklist Check off the elements you have in place for this stage of renewal.

Now that we have reviewed the LMC Process, I want to introduce you to a change management tool to help leaders, especially those on the design team, ensure that they can manage the entire process with forethought and accountability. I designed this tool, called the Master Change Plan, to avoid the common pitfalls that I have seen in organizations working on change. I cited a list of them earlier:

The Master Change Plan is a useful template to help you think through, track, and diagnose where you are in the change process. This tool allows you to annotate the entire change effort so that you can plan, integrate, and align the work that occurs during all four stages of the LMC Process. Going through the Master Change Plan process—i.e., filling out the template—is a great way to look for errors and test the feasibility of your plan to see the interdependencies, intersections, and factors that may influence it. Completing the template as a team or a team of teams usually leads to greater efficiencies in the way people work, saves time and money, creates alignment on the way forward, and enhances teamwork and collaboration across the organization and beyond.

As mentioned, you can use any change model as the foundation for starting this process. For our purposes in this book, I will use the four stages of the LMC Process that incorporate Use-of-Self, change leadership, and change management.

Begin by reflecting on a change leadership challenge you may be facing now or soon. Where do you stand in terms of the LMC Process? Consider these questions:

Now let’s review the Master Change Plan tool that I use to align and integrate a change project with an organization’s larger change or transformation. The process includes thinking about and planning for five key areas: the change journey and timeline, corporate alignment, project, supports, and communication. I will start at the top of the chart in Figure 6 to explain each area.

Figure 6 LMC Master Change Plan

Each column in the chart represents a period of time. Depending on your project, you might use the business cycle of quarters (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4) or a monthly timeline. This chart is set up to reflect four quarters, so if you use months, you need to expand the chart to 12 columns.

Using the timeline you decide on, write down in each column of the second row an answer to the question, “Where do you expect to be in the change process?” To answer the question, use the four-stage LMC Process. For example, are you creating alignment, planning for integration, taking action to implement and/or evaluate change, or renewing it? As mentioned, you could also use the seven steps of the ExperienceChange model or any other change model to map your time frame with the steps of that process.

Your answers will help you see how your work aligns with your organization’s larger purpose and anticipate where you think people might be in each period. This is a preliminary assessment of your plan; as you implement it, you may need to adapt it based on feedback you get and what you observe, experience, and hear from others.

Note that some of you may be working on large-scale transformation with multiple projects happening at the same time, or you may be in different stages of the change process, so you may need to break down the steps of your plan into individual Master Change Plans that you will eventually roll up into a single Master Change Plan. Others may be working on a single project, so filling out the template may be easier. Whatever your situation, keep in mind that change is a dance between the work that needs to be done and the people involved in the process. This is not a linear process; depending on the complexity of your change, your dance may differ from others.

Next, in the corporate row, identify the corporate or institutional activities and milestones for each period, such as checkpoint meetings and presentations to governing bodies or committees for input, decisions, or approvals. It’s useful to note key corporate activities or interdependencies that you need to consider if they might influence your project and change plans, such as reports, budget processes, production forecasts, or board meetings.

After that, use the project row to map the key activities and milestones that will be addressed in your project plan.

It is useful to think about these two rows together as you flesh out your answers. Most people tend to start thinking only about their project without regard to the corporate milestones and activities, but this can lead to a misalignment between the project and the larger organizational strategy. This part of the exercise may reveal opportunities to adapt the pace and sequencing of the project, build capacity, or deal with political issues that may arise.

An example of this comes from my experience working with a learning and development team of six people who were responsible for the leadership development strategy for their organization. When they mapped out their project based on what they envisioned as the ideal sequence, they realized they had 60 activities to deliver in the first two quarters of the year, but nothing mapped out for the balance of the year. They were also a team of just six people with a finite budget. At first they were overwhelmed and believed they could not pull off this plan. They needed to collaborate with people from other departments and access more funding to deliver the plan.

Taking a step back, they used the Master Change Plan process to realign their learning and development strategy to the larger human resource and communications strategies and their organization’s vision and strategic plan. This helped them identify opportunities where they could partner with each other within the team, and with people outside their team, to maximize their resources. They redesigned their approach, and together with the other internal partners, they developed a plan that was more realistic and feasible and led to faster and better results.

In this row, identify the support structures, processes, leadership development activities, networks, and other actions that people need to build the competencies for leading and managing the project. These may also include new tasks or project teams, more active participation from executive team members, or specific leadership and technical development activities to build new skills or implement new technologies and processes.

In this row, list the key milestones, processes, and supports that will help you create effective communications strategies to inform people and engage employees and stakeholders in meaningful conversations throughout the process. This will also help you spot opportunities to reduce duplication and make use of existing corporate and departmental communication methods, products, and processes. It also helps target what needs to be communicated and when and how to approach stakeholders, especially when an organization is undergoing significant change. Mapping your communication activities helps you collaborate more effectively and efficiently by making more visible what, why, how, and when communication needs to happen and who needs to be involved.

In the toolkit in part 2, you will find the Developing a Communications Plan Exercise to help you with this task.

A Master Change Plan can be developed for one specific project or for multiple projects that are occurring simultaneously as part of a larger transformation. In fact, there is a lot of value in doing this exercise with multiple projects and stakeholders to identify synergies, create alignment, and build better focus and capacity to lead and manage change plans. In my work with larger organization-wide change initiatives, I often conduct a Master Change Planning workshop with leaders or teams from the business and corporate services functions, change projects, or initiatives who come together for one day to develop their plans. Usually, the group attends having done some assigned prework prior to the session. Those results are then posted on the wall around the room so everyone can discuss them and learn from each other. The group works to identify and understand the following:

I offer the following recommendations to avoid some common pitfalls when using and presenting the Master Change Plan:

This Master Change Plan process will help you align your project with the larger strategic priorities of your organization. The process provides a reality check on what is realistic to achieve given tight time frames, competing priorities, and finite resources. It helps identify interdependencies and builds collaboration and teamwork across the organization that ultimately results in a stronger shared vision and buy-in for the changes.

In part 2, you will find an exercise called Master Change Plan that will help you go to the next step in developing your plan, advancing your change leadership challenge, and putting these concepts into practice.

You have learned how the LMC Framework is grounded in seven critical principles that need to guide your change plans. These principles are human-centered, universal, and necessary for any change effort to succeed and remain sustainable. To recap, they are:

Meanwhile, you also need to keep your Use-of-Self top of mind at all times. This is your most valuable instrument in your change toolkit. It is constantly at play in the seven principles of the LMC Framework. As leaders, managers, and participants in the LMC Process, we need to pay attention to our intentions and the choices we make about how we show up in the world via our thoughts, our behaviors, and the actions we take to lead and manage ourselves and others throughout the process.

Finally, you learned about the four-stage LMC Process—alignment, integration, action, and renewal. These stages form a comprehensive chronology to achieve the goals of any change effort, large or small. To build lasting culture change, it is vital that the change is well planned and aligned with the organization’s priorities. A systems approach that meaningfully engages a critical mass of employees from across your organization and partners with key stakeholders will achieve results that are far greater than the contribution of a single individual or team and that are sustainable over the longer term.

As a tool, the Master Change Plan will help you go beyond the basic tactics so you can build a holistic and integrated plan to successfully lead meaningful change.