Somewhere in Thelma Jordan’s past there is a baby. We know almost nothing about it, or how it carne into being, for that is one subject she almost never mentions. But I believe it was the reason she quit going to college, the reason she left home and joined a carnival. And doubtless it was the reason that Thelma, during her years of prosperity, always made it a practice to send home $25 a week.

Her parents had no need of the money for themselves. Her father was a public official in the small prairie city where she was born and brought up. It was one of those towns with a water tower, two or three office buildings, and a lot of church steeples jutting up out of the flat plain, and a country club at the edge of town with a nine-hole golf course, very flat. Adull sort of place, to be sure; but in the years when Thelma was an underworld girl in New York, home always seemed to be the perfect distant haven of dignity and security. Twice she went home to visit, and she was welcome; one time her big brother squeezed her so hard as she got off the train that he broke two of her ribs, and then she could not work for weeks. I don’t know what story she invented about herself for those occasions. She never stayed long. For one thing, it involved a lot of pretense and hypocrisy. And Thelma always hated hypocrites.

Thelma is a little, dark, cuddly girl, with large soft eyes of the liquid, melting sort. It was the eyes, rather than any intellectual power, that got her by during two years in college; for even the professors in a small fresh water college, with a heavy enrollment of theological students, are susceptible to the helplessness of little cuddly girls. She was a nice girl, too, but unhappy. If she had been in the country club set at home, or in the sorority set at college, it might have made all the difference in the world; she would have married well, have become one of the sprightliest young matrons in town, and doubtless have made her husband happy. But Thelma did not rate that high socially, nor yet could she be as free and easy as the factory girls and kitchen maids. She had a position to maintain, even if her father was only the street cleaning commissioner in what was hardly more than a one-horse town.

And so she was an unhappy girl, a girl of moods, despondency and bursts of irrational high spirits. It is not surprising that she got into a jam, as girls have been getting in trouble since the dawn of time. And then, to save her family from disgrace, she went away in the summer of 1931 and joined a carnival.

There often is reason to regret that this story is not a novel. If it were, we should have no doubts about Thelma and there would be no mystery about her. We should know all about her emotional tensions, and what she thought and felt, and how the hair curled down behind the young man’s ears, and why she fell for him. We should be omniscient. But that unfortunately is not the case. We know only a few things about her, and have to guess, just as we observe some and surmise much about practically all the people we know intimately and meet every day.

I should like to write fiction about Thelma. Then she would become a personification of flight, swept along and downward by strange currents over which she had no control, struggling only to keep her inner personality intact, grasping at straws and chips which she clutched as secret symbols, known only to herself, representing dignity, power and self-respect, and always secretly gratifying a grudge against men. Maybe it would make sense. Maybe it does make sense. That is the way I like to think of the real Thelma, and I may be right.

The carnival she joined was one of those half-starved shows which moves from week to week, with a portable ferris wheel, a tattooed lady, some hootch dancers, a daredevil motorcycle rider who also takes high dives into a tank, and a small army of camp followers and gyp artists with phoney gambling devices. They were rough and ready, good-hearted people of a sort Thelma had never known before, and not a bit respectable. She liked them.

Thelma did pretty well. She started selling sandwiches and soda pop at a lunch counter, but she was a good-looking girl to find in a carnival and soon was moved up to a job in a target booth on the midway. She would roll her eyes at the yokels, sell them three baseball throws for a nickel, and give the winners kewpie dolls and cheap candy in fancy boxes. Men bought baseballs for an excuse to talk to Thelma, and business was good.

Everywhere Thelma went there was sex hunger in men’s eyes, and the questing impulse of pursuit. That had once been thrilling but there was bitterness in Thelma now, and calculation. She would kid a man along, and he would spend his quarters and throw baseballs until his arm was sore, while she would exclaim in approval of his better throws. He would try to date her up, and she would string him along. It was strictly business.

One day one of Thelma’s bedazzled young men, after he had left her booth, let out a yelp that he had been robbed. His pocket had been picked. Two or three days later the same thing happened again, and this time Thelma knew what it was all about. She had her eyes open and her suspicions were confirmed. The pickpocket was that slick young man from New York whom she had seen around the carnival, always apparently prosperous, but with no visible means of making money. She had been curious about him, but when she had asked about him no one had given her a direct answer. They had just shrugged their shoulders. Now she buttonholed him and gave him a piece of her mind.

“Say,” said Thelma. “You better lay off my customers.” Perhaps the light-fingered gentleman had a good sales talk, and maybe Thelma was a bit sweet on him and easily influenced. I prefer to think that she was the smart one, for it is my impression that she had a hard winter ahead, and only a few months in which to make a grubstake before she lost her girlish figure. whatever happened was unethical, reprehensible, even criminal, for the conversation ended with Thelma becoming the pickpocket’s partner.

Before long Thelma became a most expert decoy. She was the femme fatale of that carnival. There was an anesthetic quality about her eyes. Let a yokel but look into them deeply enough and he was hypnotized. When he came to, his wallet was gone. But he knew very well that Thelma had not taken it, for she had never put her hands near him.

The carnival moved down through Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. Thelma made $30 a week out of her regular job, but in a good week her sideline often paid several times that much. By November, when the carnival closed down for the winter and turned her loose in Texas, she had accumulated a good bankroll and had learned many things which they do not teach in college. She never did any actual pocket-picking herself, for that would have been risky; and so when her past came up to bother her in later years, she was able to deny with conviction that she had ever been a pickpocket. She gave up the whole thing after that November. This was not because of any especial pity for the men who pursued her, for she thought they were fair game, but rather because it made her uncomfortable to be tied up in something dishonest. Besides, she knew her partner was cheating her all along, but could not prove it or do anything about it at all. So she parted with him, and went to New Orleans for the winter.

Thelma’s next year is obscure. Her family sent her some money that winter, and I assume it was in that spring of 1932 that the baby was born. Then she adventured eastward, making her living I don’t know how. We find her at the end of the year in a hotel room at Washington, getting married to a big, fine-looking fellow from Texas, who went by the name of Bill Cook. She was tired of adventuring and being on her own, and the prospective security of marriage to a fine young man made her unbelievably happy. Later Thelma said the marriage was a phoney, with a fake preacher and a fake license. Whether it was or not makes little difference. It was the means by which a pimp fastened himself on Thelma.

There is an old, well-established system that men follow to get girls into prostitution.1 First the pimp finds a young attractive girl, not too smart, who is on her own and unhappy, who usually has just been through an unfortunate marriage or love experience. He is nice to her, takes her around, spends money on her, becomes her lover. Then she meets friends of his, glamorous girls with fine clothes, and money to spend. It is a great adventure, running around with fast people. It is a shock to learn that their money comes from prostitution, but the pimp preaches tolerance, broad-mindedness. When the soil has been thus prepared, a financial crisis arises. Often the girl’s lover disappears for several days, during which she is frantic with worry. Then he reappears, looking worn and dirty, with the news that he has been in jail and must go back to prison for a long time unless he can raise the money quickly to fix the case. That is the girl’s cue for self-sacrifice. She is the one who can raise the money and there is only one way to do it. She volunteers. The man’s cue at this point is to protest, to bewail the situation, to insist that he is going to prison. But, if he has worked it properly she insists upon saving him. The one basic rule of all this is that the man must never urge the girl to become a prostitute; she must do it of her own free will, or at least think that this is so. For, while a man may strongarm a girl or otherwise force her into a bawd’s life, this does not establish the proper emotional relationship; the girl may resent it and later skip out on the pimp, leaving him without a meal ticket, right back where he started. But once a girl is started in prostitution, the chances are she will continue to do that kind of work, as long as she can get it. For it has a corrosive impact on a girl’s personality, and she reacts violently, for the human ego is a resilient thing. The girl develops a reckless bravado. She takes refuge in drink, narcotics, or other expensive habits, and by them is in turn imprisoned. Sometimes a girl tries to break away, but usually she goes back. Prostitution makes a girl much more money than working in a cafeteria or bargain basement, and is a lot easier on the feet.

In Thelma Jordan’s case the financial emergency was that Bill Cook had a wonderful business opportunity in far-off Texas, and no money to get them there. Once in Texas, they would be fixed. There would be money, and security, and a home of their own, and babies. But now there was no money.

Thelma fell for it, and took the leap. She made contacts through Bill’s friends, and started going on calls to hotels in Washington. Soon she accumulated a bankroll and they were off to Texas.

But in Texas Bill’s job failed to materialize. Instead he got her work in a joint at Houston, and came around to collect her money twice a week. Thelma’s hopes for a home life faded. She was in a worse jam than ever.

Thelma never got out of the house except when Bill was with her; and even if she did give him the slip she knew she would be a lone helpless girl in a strange country. She resolved upon an indirect resistance. She did not complain about the life, but she did complain about Houston. She knew she was good enough for a bigger town than this, where she could make more money, Thelma told him. Bill ought to take her back to Washington, or even to New York. This time it was Bill who fell for a line, and so it was they began to work the hotels.

She soon found there was a lot she did not know about the business, but she learned rapidly. She still wanted to get rid of Bill Cook, and was just waiting for an opportunity to shake him, but the impulse to run away and get out of the business had grown weaker and weaker. It was about this time that Thelma started drinking brandy steadily. Any experienced bartender will tell you that is bad. A man can do very well on a steady diet of Scotch, or even gin, but when he starts pouring down a steady stream of brandies something is going wrong. Brandies taken one after the other make maggots in the brain, or something. Or maybe it’s maggots in the brain that demand brandy. Bartenders and people told Thelma she should try Scotch for a change, that too much brandy was bad. But by that time she did not care much. From eye-opener to nightcap it was brandy for Thelma.

One thing Thelma did not like about New York. In Texas a two-way girl had been a curiosity, and there had been no great demand for her services, but here in the metropolis a girl was expected to be versatile in the most degrading ways. Thelma just couldn’t bring herself to it, though it appeared her squeamishness was likely to stand in the way of a successful career. Then she started observing things and using her brains, and discovered that in the craze for versatility, certain specialties had been almost overlooked. Soon, in addition to the normal run of business, she had developed herself a lucrative special clientele.

Thelma first got the idea one night when she had a call to a drugstore on Broadway, which seemed a queer place for a call. When she got there, the proprietor was waiting for her in the back room behind the prescription counter. He had there a disreputable old worn-out pair of shoes, and all he wanted her to do was to put on the shoes and walk up and down in front of him a few times. When she did so it seemed to please him very much, and he gave her $10 for the job. What easy money! Thelma thought. How long had this been going on?

Thelma now found that her education came in handy. She could read better, had a more inquiring mind than most other girls in the business. There were, she discovered, certain esoteric books, sold under the counter in some shops, hoarded in libraries by strange old men, which told all manner of strange things about the sexual vagaries of mankind. She couldn’t get far with Krafft-Ebing, because every time he got really interesting he wandered off into Latin and her Latin had never been good. But the others were easy reading.

There were lots of peculiar men in the City of New York. Soon Thelma developed a code of conduct all her own for dealing with them. She would have nothing to do with men who wanted women to degrade themselves, who wanted to humiliate a girl, or be cruel to her. But if a man wanted himself humiliated, or wanted to make a complete fool of himself, that was nothing for her to worry about. She could help him out, and probably add a few frills he had not thought of. All this was a help to Thelma’s ego. She was a cut above the other girls.

Her work had one thing in common with journalism: she met so many interesting people. She also had many queer jobs. One man took her to Florida with him in the season of 1935, and all she had to do was to stand by, a nude, attentive spectator, an acolyte you might say, while he performed strange sexual rites involving the slaughter of a pigeon. She had a very nice time at Miami Beach.

But the strangest of all was a man she met but once. He was a prominent New York City mortician and Thelma was sent to see him, I believe, by Peggy Wild. She went with the understanding that she had never been there before, and would never go again; that he insisted upon.

She was received by a solemn butler, in black garb, who took her evening wrap and left her to wait in a small reception room, a stuffy little place where Thelma sat uneasily in a carved mahogany chair. As she waited she heard distant organ music, playing a funereal air. It made Thelma think of a time she had gone to a cremation over in Queens, for a little girl she knew. She felt rather out of place, in her pert little yellow evening dress.

At last the butler came again, and motioned for her to follow. She went behind him along a gloomy passage. Then he opened a door, stood aside for her to enter, and closed the door behind her.

Thelma found herself in a large, high chamber, the walls of which were hung from ceiling to floor with unbroken folds of black velvet. The organ music, though muffled, was stronger now. The only light came from two large candelabra at the far end of the room. And there, between the candles, in their ghastly light, was a coffin. It was an ornate coffin, and the lid was turned back, revealing a lining of tufted white satin.

Hesitantly, nervously, Thelma stepped forward, led toward the coffin by some unseen compulsion. Now she stopped suddenly, for in it lay a corpse. Thelma had never seen a dead man before, and it was ghastly. The face had the blue pallor of death, the waxy consistency, and its lips were rouged as though to make it look more natural to the beloved ones of its family. Thelma drew still closer, moved on by some horrid fascination.

Now suddenly she felt her feet gripped to the floor, herself frozen in a rigid tension of terror. The corpse was moving!

Its eyes opened. Its lips fell apart from grinning, uneven teeth. Its head turned. And now, slowly, stiffly, it sat up in the coffin, and turned upon her its glaring, staring eyes.

Thelma, standing there frozen, heard a scream. It was a long, piercing, agonized scream, a vocal convulsion of fright. Then all at once she knew, she realized, it was she herself who was screaming. That realization brought release. Her knees quaked and trembled, and on her shaking legs she turned madly and staggered toward the door, which was opened by an unseen hand and led her into the outer corridor.

There stood the black-garbed butler, calm, cool, funereal; holding her evening wrap for her shoulders.

“That will be all tonight, Miss,” he said, and handed her a plain white envelope.

Down the block, under a street light, Thelma opened it. It contained a $100 bill.

It was Thelma Jordan, I think, who said that a girl keeps a pimp because, when she wakes up with a hangover on a cold, dark, gray morning, she likes to be able to look at some one lower than herself. But Thelma had a sharp tongue, and the remark had all the usual pitfalls of the epigram. The facts go deeper than that.

The universality of the pimp is one of those apparently inexplicable laws of nature. Practically every prostitute has one, whom she supports or whom she helps other girls to support. One fellow, who has had a certain amount of personal experience along that line, tells me that the only reason he can see for this is that the girls are dumb and haven’t any sense.

Doubtless the phenomenon goes deep into the recesses of the human heart. There is no one in the world, I suppose, who leads a more lonely life than a prostitute. The men she meets are mere passing phantoms; her girl friends are in-substantial moths, here today and gone tomorrow. She is cut off from her family, from all the normal contacts of life. But her pimp is hers. He is interested in her, for a mercenary reason, perhaps, but still interested.

There are certain practical reasons for having a pimp. If a girl is pinched and taken to the police station, the pimp is the only one she can really count on to make a holler and see that she is bailed out. Then too, the girl is usually young and inexperienced when she arrives in New York, and her man makes contacts for her, sees that she gets a break. But the emotional reason is the more compelling. A girl has her man. He may be nothing to brag about, but he is hers.

Thelma Jordan had been in New York several months, and she still had her pimp, Bill Cook, who merely loafed, took her money, and fooled around with other girls when she was working. Thelma did not like him any more, she even hated him. They quarreled, for he took it as a personal affront every time she sent home her $25 a week. She thought about shaking him, but could not quite bring herself to it. He was the only person of her own in all New York, and he had got to be a habit, like brandy. It would have been easier to ditch him, if he had been a husband.

In the spring of 1934, Thelma started booking with Pete Harris now and then. Working the hotels was a very speculative business, but you could be sure of good money if you worked in a joint. One of the first places where Thelma worked was May Spiller’s joint in West Fifty-fourth Street. Spiller wasn’t really her name, but she used that because she was running the place for Bennie Spiller, who really owned it. All Thelma knew about Bennie was that he was a shylock who hung out and did his business at a saloon in Fifty-fourth Street, and he came to the house every day to take the money out, so it would not be there in case of a holdup. Bennie would hang around a while when he came over, kidding with the girls, and he quickly took a liking to Thelma.

This Bennie Spiller was a slim fellow with a long nose and receding forehead, but was no inconsiderable person. He was hardly more than thirty years old, but already had made a lot of money. He had started out in Philadelphia, very young, in prostitution and bootlegging; and, not being a racket man, he had been smart enough to hold onto his dough. When Philadelphia got a bit hot for him, about 1930, he cashed in and moved to New York. Though he did not advertise it, he already had a bankroll of about $75,000, and soon he had his fingers in a lot of things. His brother Willie ran a horse book which Bennie backed, and Bennie devoted his main attention to the shylocking business, lending money to sporting and underworld people. If he lent $5, he would collect $6 the next week, which amounted to 1000 per cent interest, and if he lent $50 he would collect $6 a week for ten weeks, which was several hundred per cent. It was a profitable business. Then he also had May Spiller’s on the side, and his shylocking gave him chances to get in on a lot of deals.

Before Thelma had finished her first week at May’s, Bennie dated her up and took her out to a night club, after her night’s work was done. They had a good time, Thelma was very gay, and as the night went on, Bennie got more and more fond of her. Finally they went riding home in a taxi. Thelma snuggled over against Bennie’s shoulder, and he put his arm around her.

Suddenly Thelma pushed him away.

“Say, quit that!” she said. “Listen, Mr. Bennie Spiller, you needn’t think that just because I work in a joint, I have got round heels to fall for every fellow that comes along. I understood that this was a social occasion!”

For that was something Thelma was very strict about. Business, she always insisted, must be a positively impersonal matter, and in society she did not expect to behave as if she were working. She remembered she had often heard it said, you mustn’t mix up business and friendship, when somebody wanted to borrow some money or something. Thelma sometimes thought she would go batty if she didn’t keep herself a little private life. Except when she was having one of her rattle-brained, reckless spells, Thelma was a prim girl. She was even, as girls from the prairies are likely to be, a little bit prudish.

Bennie was dumbfounded. He said good night and went home in a daze. What a girl that Thelma was! Bennie thought back through the years, and he could not remember when he had ever known a girl as refined as Thelma. He could not remember when he had been so hot and bothered. Criminee! This must be love!

Bennie and Thelma saw a lot of each other after that. They went to night clubs after she was done, or to a midnight movie. Thelma told him about her home town, and college, and the carnival and Bennie told her about Philadelphia and the shylock business.

Thelma even told him about her troubles with Bill Cook, for Bill had been raising the devil lately, out of jealousy OV:!r Bennie’s attentions to Thelma. She told Bennie she did not know what she was going to do about him, and wished she could ditch him.

One night Bill did not come home. The next day Thelma did not see him. The day after that she told Bennie that Bill was missing.

“I guess maybe he is in Texas by this time,” said Bennie. And then he told her. It had made him mad to think of Thelma having to support that fellow Bill, especially when she wanted to get rid of him, so he had got a couple of fellows to talk to Bill.

These friends of Bennie’s were very nice fellows and had not done anything to Bill, but they had told him to take a powder and had gone to the train with him to see that he got on it.

When Thelma realized that at last she was rid of Bill, she was overjoyed. She told Bennie she did not know how to thank him. It was very nice, she told Bennie, that she had someone like him who was fond of her and would look out for her.

Don’t mention it, Bennie said, it was nothing. Being as he was in the shylock business, he always had to have fellows around who would persuade people that they should not be deadbeats. These fellows were very strong, but they were very nice too, and they had been glad to do a good turn for Thelma.

Bennie told Thelma that any time she wanted to work, she could work at May Spiller’s. He would be glad to have her, because she helped build up the business. That was nice, because May’s was a good house, and most of the customers paid extra. It was a three-girl place, and took in on the average $1,500 a week, and a girl could often clear $200 in a week there for herself. Thelma did not want to wear out her welcome, but she did work at May’s one week out of nearly every month that year. It was nice, too, that she could keep her money for herself, and still have a boy friend like Bennie Spiller.

Thelma and Bennie were seeing each other almost every night now, but did not live together. Bennie had his home downtown, in Twelfth Street, and Thelma lived in Ninety-sixth Street, with Red Head Mary Morris, whose boy friend was Ralph Liguori’s partner, and that was how Thelma came to know Nancy Presser so well.

Bennie and Thelma were very happy when they were together, for they were that way about each other, and sometimes they would remind each other about their courtship, and how it was six long weeks before Bennie could make Thelma.

Bennie thought he was very lucky to have a girl friend like that. Not a man he knew had a girl friend as refined as Thelma.

When Jimmy Lane threatened to kidnap Bennie Spiller, in the spring of 1935, and clip him for ten grand, it started a complex and fantastic chain of events. Bennie and Jimmy had many a good laugh over it together later on.

The upshot of it was that Thelma’s boy friend, Bennie, was lifted to an eminence he had never expected, and became a member of the prostitution combination itself.

It all started with the $25 a week protection which was being paid by Marty Greenfield, a brothel keeper, to a mob of strong-arm men led by one Cockeyed Johnny. This same Cockeyed Johnny mob was also on Spiller’s payroll for $25 a week.

Business was very bad in the underworld in those days. New rackets were developing, but they had not yet replaced the Prohibition bonanza, and the unemployment problem was acute. Gunmen, salaried assassins who in the past had always been good for $75 or $100 a week, were in some cases working for as little as $25. Others were off the payrolls entirely, foraging for themselves, operating independently in small mobs under the loose patronage of their former bosses. The business of protecting joints was bread and butter to these groups.

One of these mobs, rivals with Cockeyed Johnny, was led by Bob Davis, who has since committed suicide in jail, and Jimmy Lane, now serving a long prison term for a jewel robbery in Madison Avenue. Lane and Davis started to take Marty Greenfield’s joint away from Cockeyed Johnny, and Johnny raised a squawk. He protested bitterly.

“All right,” said Jimmy finally. “You take Marty Greenfield back. He ain’t worth a damn anyhow. But I'm going to take Bennie Spiller. I'm going to snatch him, and I can take him for $10,000.”

As news spread along Fifty-fourth Street that Jimmy Lane was going to snatch Bennie Spiller, there was hell to pay. Cockeyed Johnny knew he wasn’t big enough to handle this, so he ran to Little Davie Betillo. Bennie Spiller himself got Nick Montana to take him down to Little Davie Betillo because at a time like this protection is really wanted.

And when Marty Greenfield heard about it, he was scared too, for he was in the middle. If Bennie should be kidnapped in a quarrel over Marty, somebody then might snatch Marty to get even for Bennie. Marty grabbed a telephone and called Philadelphia. He came from there and people in Philly liked him, because he had always been good for some dough when the boys got in trouble. So he called up a racket boss over there—named Murphy, I believe—and told him what was happening.

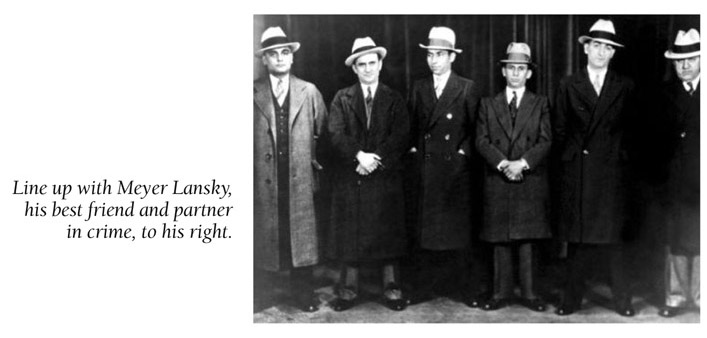

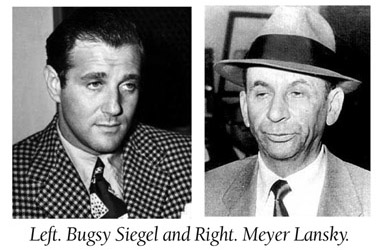

Now this was after the murder of the Philadelphia racket boss Bill Duffy, and the top men in Philadelphia were Bug Siegel and Meyer Lansky, the Bug and Meyer mob of the big Combination. So Murphy called up Bug Siegel at the Waldorf-Astoria, and Bug Siegel got hold of Charlie Lucky, and Lucky passed the word on to Little Davie not to let Jimmy Lane put the snatch on Bennie Spiller so that Marty Greenfield would not get in trouble. That is the story that was told along Fifty-fourth Street after the crisis was over.

But in the meantime Little Davie was already in action, talking to Bennie Spiller himself. Little Davie needed money. Everybody in the underworld needed money in those days.

“So they want to take you for ten grand,” said Little Davie. “Bennie, you got $10,000?”

“Well,” said Bennie, more frank than usual because he was on the spot, “I could get it up.”

“I’ll tell you,” said Davie. “You bring me that $10,000. I will take care of them guys. I will kick the bellies off them louses. And we will put the money to work in the combination.”

So Little Davie sent for Jimmy Lane to come downtown, and it is said that Jimmy sent back word that he hadn’t got time, for Jimmy was tough. They told him Davie was very sore at him, but still Jimmy said he hadn’t no time to go down. Having thus stated his position, he decided to take a jump downtown and see what Little Davie had to say. For nobody fooled around with Davie very long.

He found Davie in that cafe at 121 Mulberry Street, and a lot of mugs were hanging around outside there, so Davie said to come in the back room where they could talk. When Jimmy told his friends about that later, it was a build-up for him. He was tough, especially good with his fists. He could have slapped Davie all over the place with bare knuckles. But Davie did not use bare knuckles, and very few guys would have cared to go in that back room with him alone. Jimmy’s friends took his version of that conversation with a grain of salt, but when they heard that he had gone in the back room alone with Little Davie, they figured that Jimmy Lane was no man to fool around with. A guy with that much guts would go far, and they thought it was too bad when he got caught robbing that jewelry store in Madison Avenue.

“Look,” said Davie when they got in the back room. “I got a lot of mouths to feed here. Now do me a favor and lay off this Bennie Spiller. He is my man. There is many a favor you will want done.”

Jimmy knew that Davie never had had Bennie up to now, but now he had him and he was going to clip him. So Jimmy said O.K. and they parted the best of friends.

Bennie’s difficulties had turned into a windfall of good luck, or so it seemed to him. The percentage they gave him in the combination was a small one, to be sure. But it elevated his importance. He was in the big time now. He teamed up with Jimmy Fredericks in his shylocking, and the business did well, because they had the right kind of backing and when Jimmy or Bennie told anybody to pay up, why, he paid up.

Bennie thought Little Davie was the nuts after that. He had a case of hero worship. Davie had a smooth tongue when he wanted to use it, and Bennie was being clipped for his dough without his knowing it. It took an artist to do that. Bennie did not know until long later, when Tommy Bull tipped him off after they were in jail, that his part in the combination had been marked down for liquidation, both financial and personal, by means of a bullet. But the O.K. on that had never come down from higher up.

Bennie did not fit in with that crowd. He might be a slick article, a numbers man, a bookmaker, a shylock, a pimp or even a male madam, but he would never really be a racket man. The others felt that, and they took out their feeling in what seemed to Bennie a lot of carping criticism, hauling him on the carpet, mainly about his intimacy with that prostitute, Thelma.

“Bennie, are you pimping for that girl?” they would ask.

“Naw, I just like her,” Bennie would say, but that did not satisfy them. So at one of their regular Tuesday evening meetings in November they told Bennie to go get Thelma and let them talk to her. Bennie went uptown to Thelma’s apartment and got her, for she was not working that week, and took her downtown to Celano’s Restaurant, in Kenmare Street, around the corner from Mulberry. There sitting at a table in a back corner were Little Davie, Little Abie and Tommy Bull. Bennie introduced her. She knew Jimmy Fredericks, but it was the first time she had met these bosses.

“Thelma,” said Little Davie, “have you been giving money to Bennie?”

“No,” said Thelma, “I don’t give him any money.”

“You know, you can’t give any money to Bennie,” said Davie, “Bennie can’t take money from you and stay in the combination.”

“I know you been making a lot of money here lately,” said Tommy Bull. “If you ain’t giving it to him, what are you doing with it?”

So Thelma told them she was spending her money on clothes and brandy, and sending the rest of it to her folks at home.

''Well,” said Little Davie, “if we ever hear of Bennie taking any money from you, he will get lticked out of. the combination. And if you are going to go with Bennie, work as little as possible.”

Because they did not want to associate with a pimp.

1 This explanation comes from Cokey Flo.