Samuel Cabble, an African-American Private in the Union Army, Promises His Wife That Slavery, the “Curse of This Land,” Will Be Crushed & Capt. Francisco Rice Assures His Wife That “Although the Day May Be Dark as Ever,” Their “Sacrifices Have Not Been Made in Vain”

In the beginning of the Civil War African Americans pleaded with and even petitioned the government for the opportunity to fight. But it was to no avail. Political and military leaders feared it would only stimulate recruitment efforts in the South, and many held the racist view that blacks were cowardly, lazy, and untrainable. But as Union casualties escalated and the military command recognized the need for increased manpower, small regiments of black troops were formed starting in the summer of 1862. After issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, President Lincoln launched an aggressive campaign to recruit black soldiers. On July 18, 1863, the Massachusetts Fifty-fourth, the first all-black regiment organized in the North, demonstrated extraordinary courage against impossible odds during an attack on Fort Wagner in South Carolina. Other regiments would also shatter every stereotype hurled at them. Despite being underpaid, assigned menial tasks, and given inferior medical attention, young black men continued to volunteer in droves. An estimated 180,000 African-American soldiers served in the war, representing nearly one-tenth of the Union army, and over 37,000 of them died. Twenty-one-year-old Samuel Cabble (possibly Cabel), an escaped slave, enlisted with the Massachusetts Fifty-fifth Volunteer Infantry in June 1863. Soon after, Cabble sent the following letter to his wife back in Missouri. (Correspondences by slaves are exceedingly rare; slaves still in captivity were punished severely—even put to death—if they were caught writing or reading any materials, particularly letters.)

Dear wife i have enlisted in the army i am now in the state of Massachusetts but before this letter reaches you i will be in north carolina and though great is the present national difficulties yet i look forward to a brighter day when i shall have the opertunity of seeing you in the full enjoyment of freedom

i would like to no if you are still in slavery if you are it will not be long before we shall have crushed the system that now opreses you for in the course of three months you shall be at liberty. great is the outpouring of the colored people that is now rallying with the hearts of lions against that very curse that has separated you and me yet we shall meet again and oh what happy time that will be when this ungodly rebellion shall be put down and the curse of our land is trampled under our feet

i am a soldier endeavry to strike at the rebellion that so long has kept us in chains. write to me just as soon as you get this letter tell me if you are in the same cabin where you use to live. tell eliza i send her my best respects and love ike and sully likewise

i would send you some money but i no it is impossible for you to get it i would like to see little Jenkins now but i no it is impossible at present so no more but remain your own afectionate husband until death

Samuel Cabble

At close to the same time that Samuel Cabble (who survived the war) sent his letter, thirty-one-year-old Francisco Rice was writing to his wife, Adelia, to articulate the cause for which he was fighting.

Our prospects of triumphant success in this great effort to maintain inviolate the blessings of government achieved by our fathers in the american revolution are brighter now than they ever have been … [But w]hen I think of your sufferings I cannot restrain my tears. Yes, the ragged and bronzed soldier has shed many, many a bitter tear when thinking of and listening to the recital of the wrongs inflicted upon my people—my wife, my children.—Our enemies are a vile and barberous race. Hystory does not give account of so wanton and wicked a war waged with so much atrocity and inhumanity, as that now waged against us by the infernal Yankee nation.

Rice was a Confederate captain from Alabama under General Nathan Bedford Forrest. A doctor by profession, Rice served as a state senator before the war and maintained a small family farm. While he was away fighting, Union troops plundered his farm and drove off his livestock. In late May 1863 Rice expounded on his hatred of the Yankees and his allegiance to the ideals he believed were at issue in “the war of Northern aggression.” (The last page of the letter is missing.)

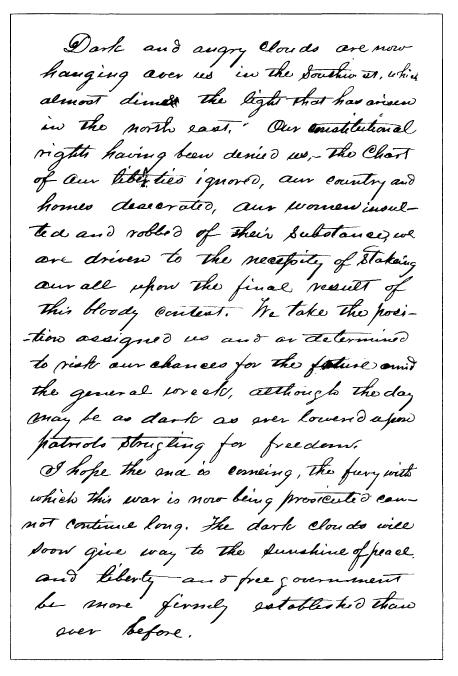

Spring Hill Tenn May 25/63

My own dear Wife

We are again at this place Picketting in front of Franklin after an absence of one brief month. The scenes through which we have passed, and the part we have enacted in this great Tragidy will be properly recorded in the hystory of this revolution. I will not detain you with a detail of our march from this place to Courtland Ala.—the fight at Town Creek or the expedition from there to Rome Ga. and the capture of Col. Strait and his Brigade of Independent Rovers, within 20 miles of that place.

“All this is familiar as household words.” Within this brief period, the enimy has measured armes with us upon more than one well fought battlefield. Our powers of indurance have been tested and the patriotism of our citizens of every age and sex sorely tried.

Dark and angry clouds are now hanging over us in the Southwest, which almost dims the light that has arisen in the the north east. Our constitutional rights having been denied us.—The Chart of our liberties ignored, our country and homes desecrated, our women insulted and robbed of their substance, we are driven to the necessity of stakeing our all upon the final result of this bloody contest. We take the position assigned us and ar determined to risk our chances for the future amid the general wreck, although the day may be as dark as ever lowered upon patriots strugling for freedom.

I hope the end is comeing. The fury with which this war is now being prosicuted cannot continue long. The dark clouds will soon give way to the sunshine of peace, and liberty and free government be more firmly established than ever before.

During this time many a noble Son of the South has fallen in defense of that liberty to which we are entitled by the laws of nature and of nature’s God. These sacrifices have not been made in vain. A just God will award us our proper place among the nations of earth. Those now clad in mourning will again be made to rejoice and our land to bloom and blossom as the rose. The names of our departed comrades will be kept as precious jewils and transmitted to generations yet unborn, as the bright luminaries of the 19th century. But though hystory should never repeat their names or honest men report their fame, the justice of our cause demands that these offerings should be made. Our Redeemer for our sake suffered upon a Roman Cross, and why should not we a degenerate race suffer by the hands of wicked men.

I know that you and my children have a just claim on my time, my talents and my life, the two former at present though painful to you, for the time being is surrendered, the latter I know you can never be willing to give up. And I firmly believe that you will not be called upon to make the sacrifice. I am impressed with the belief that I will survive this struggle and return at the close of the war in safety to your fond imbrace, there to remain while we both are permitted to live.

But enough of this. My health is good. There is no sickness among the members of my company who are here. Wife you alone can imagine the pleasure it gave me to see you and be with you.

I exceedingly regret that I could not be with you longer. I feel that I have not been treated with due courticy by my superior officers.

Rice survived the war and returned to Alabama, where he and Adelia raised five children.