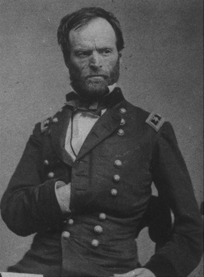

War, to Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, was neither romantic nor glorious. It was destructive beyond comprehension and relentlessly cruel. But few commanders waged war with more ferocity than Sherman himself. “War is the remedy our enemies have chosen,” he contended, “and I say let us give them all they want; not a word of argument, not a sign of let-up, no cave in till we are whipped—or they are.” Striking out from Chattanooga in early May 1864 with 100,000 men, Sherman was under orders from Grant to shatter Joseph E. Johnston’s combined Confederate armies and seize Atlanta. Sherman vowed to “make Georgia howl,” inflicting so much damage and suffering on the South the very spirit of the rebellion would be crushed entirely. “We can make war so terrible,” Sherman declared, “and make them so sick of war that generations [will] pass away before they again appeal to it.” Sherman emphasized often in his letters that he bore no personal animosity toward the South; indeed, having spent most of his adult life there, many of his oldest friends were Southerners. One of them, Annie Gilman Bowen—the only pro-Union member of a secessionist family—maintained a friendly correspondence with Sherman during the war. In the following letter to Bowen, Sherman laments how he is perceived by her relatives, but, in his characteristically impassioned style, declares that the South is solely to blame for whatever terror is to come.

Head-Quarters, Military Division of the Mississippi, In the field, near Marietta Geo. June 30 1864.

Mrs. Annie Gilman Bowen,

Baltimore Md.

Dear Madam,

Your welcome letter of June 18 came to me here amid the Sound of Battle, and as you say, little did I dream when I knew you playing as a school girl on Sullivan’s Island beach, that I should control a vast army pointing like the swarm of Alaric towards the Plains of the South.

Why oh why is this? If I know my own heart it beats as warmly as ever towards those kind & generous families that greeted us with such warm hospitality in days long past but still present in memory, and to day were Frank and Mrs. Porcher, or Eliza Gilman, or Mary Lamb or Margaret Blake, the Barksdales, the Quashes, the Poyas, indeed any and all of our cherished circle—their children, or even their children’s children to come to me as of old, the stern feelings of duty & conviction would melt as snow before the genial sun, and I believe I would strip my own children that they might be sheltered.

And yet they call me barbarian, vandal, a monster, and all the epithets that language can invent that are significant of malignity and hate. All I pretend to say on Earth as in Heaven, man must submit to some arbiter. He must not throw off his allegiance to his Govt. or his God without just reason & Cause. The South had no Cause, not even a pretext. Indeed by her unjustifiable course she has thrown away the proud history of the Past, and laid open her fair country to the tread of devastating war. She bantered & bullied us to the Conflict. Had we declined Battle, America would have sunk back coward & craven meriting the Contempt of all mankind. As a Nation we were forced to accept Battle, and that once begun it has gone on till the war has assumed proportions at which even we in the hurly burly sometimes stand aghast. I would not subjugate the South in the sense so offensively assumed, but I would make every citizen of the land obey the Common Law, submit to the Same that we do—no worse no better—our Equals & not our Superiors.

I know and you know that there were young men in our day, men no longer young but who control their fellows, who assumed to the Gentlemen of the South a Superiority of Courage & Manhood, and boastingly defied us of northern birth to arms. God knows how reluctantly we accepted the issue, but once the issue joined like in other ages, the Northern Races though slow to anger, once aroused are more terrible than the more inflammable of the South—Even yet my heart bleeds when I see the carnage of Battle, the desolations of homes, the bitter anguish of families, but the very moment the men of the South say that instead of appealing to War, they should have appealed to Reason to our Congress, to Our Courts, to Religion and to the Experiences of History then will I say Peace—Peace—Go back to your point of Error & resume your places as American Citizens with all their proud heritages.

Whether I shall live to see this period is problematical, but you may, and may tell your mother & sisters that I never forgot one kind look or greeting, or ever wished to efface its remembrance, but in putting on the armor of war, I did it that our Common country should not perish in infamy & dishonor.

I am married—have a wife and six children living in Lancaster Ohio. My career has been an eventful one, but I hope when the clouds of anger & passion are dispersed and Truth emerges bright & clear, you and all who knew me in early years will not blush that we were once close friends. Tell Eliza for me that I hope she may live to realize that the Doctrine of “Secession” is as monstrous in our Civil code, as Disobedience was in the Divine Law. And should the Fortunes of War ever bring your mother, or sisters, or any of our old clique under the Shelter of my authority I do not believe they will have cause to regret it.

Give my love to your Children, & the assurances of my respect to your honored husband. Truly,

W. T. Sherman Maj. Genl.

Convinced that Joe Johnston’s inability to halt Sherman’s steady march toward Atlanta was a weakness of will, Jefferson Davis replaced Johnston with thirty-three-year-old John Bell Hood as commander of the Confederate army. Hood, who was crippled in the arm at Gettysburg and had lost a leg at Chickamauga, took the offensive and attacked the Union forces repeatedly outside of Atlanta in late July. After several failed assaults, costing 20,000 men, Hood withdrew his army behind the city’s ramparts. Sherman had no desire to repeat previous Union disasters by storming entrenched positions only to have his soldiers wiped out in waves. So he cut off supply routes to Atlanta and began a constant bombardment that would last a month. During the siege, Sherman received a letter from a friend named Silas Miller, who occasionally sent gifts and kept Sherman informed on political and social matters in Northern cities like New York, where riots had flared the previous year after a draft was announced. (Immigrants, unlike wealthier citizens, did not have the means to pay “commutation fees” of several hundred dollars or hire replacements to avoid enlistment, and they lashed out most vehemently against blacks, whom they blamed for the war. Mobs set fire to their homes, churches, and even an orphanage, and at least two black men were lynched.) As the presidential campaign reached its final months in August 1864, tensions in the North between “traitorous” Copperheads—the antiwar wing of the Democratic party—backing George McClellan and “negro-hugging worshippers” of Abraham Lincoln were at a fever pitch. Sherman, though displeased, was not surprised.

Headquarters, Military Division of the Mississippi In the Field, Near Atlanta Geo.

1864 Aug. 13

Dear Miller,

I have your last letter from the Galt House, also the box of cigars (five boxes well put up in a larger one) sent by you through Col. Sawyer. I fear, my Dear Friend, I am taxing your kindness & generosity beyond the bounds of propriety. Mrs. Sherman has repeatedly asked me if I had paid you for certain blankets washed and other matters almost out of my memory, and unless you limit your acts of benevolence to the poor & distressed soldier from down in the Land of Dixie I must begin to look about to square accounts.

But I assure you I am far from unmindful of these repeated favors & only hope I may have it in my power to reciprocate them. Besides laboring with an earnest & I believe patriotic desire to build up & fortify a Govt. worthy of the land we have inherited I am not aware that I have merited at your hands such bounteous Gifts.

I have read your observations concerning matters & things North, and though what you say is painful to contemplate still to me not alarming. Anarchy is one of the steps through which we are doomed to pass before men become tamed to a degree to deserve civilized Govt. In a country where the People Rule, the local prejudice of each spot has its representation. If you have a tooth ache you little heed the pains of the poor fellow in the next room with a broken leg.

So the People of New York, feeling high taxes and the little vexations caused by this war, little heed the dangers & trials through which we pass, and go on with their own notions. Little dreaming that this whole Land is so united in interest that a disease pervading one part will reach & poison the whole unless it be eradicated & cured. The Copperheads at the North are a voting people, who, simpletons as they are, think that upon their votes enemies will lay down their arms. Why these fellows in Atlanta have a more supreme contempt for the sneaks in Indiana & New York who claim to be the Friends of Peace, than they do for this Army that is pounding away for their destruction.

The time is not yet for reaching these fellows, but when the Army begins to make itself felt at the North, and tell these sneaks who are trying to control the Policy of the Country in the absence of the Army, that there is no such thing as property without Govt. and that if they don’t behave themselves they shall have no vote, they will change their tune, for their money & property will go and they be left mere sojourners in a land they would not fight for in its hour of danger.

I believe the draft will be made & enforced—that our armies then having an unfailing supply of recruits to take the places of the dead, wounded & sick, we can go on making swathes through the South that cannot be patched up. I can easily pass round Atlanta now & go on but for the Present prefer not to do it, but when the time comes I will. I want to see the Virginia Army in motion again. Also one from Mobile. It is no use besieging Mobile. An Army can make a circuit round it, cutting all its communications.

Fort Morgan too can be watched by a single ship & cannot be supplied. Its days are numbered. If our armies were promptly reinforced, we are now in position to strike home.

I am sorry to see Bullitt & others in trouble. This is no time for them to breed trouble. They should defer the discussion of abstractions till we have Peace. If you see Bullitt tell him as much for me, that he is intelligent enough to know that at a time like this we should sink our opinions on minor matters and deem the Great End Union—then if any wrongs have been done, any false policy pursued, we can sit down & reason together and Truth will prevail—when a ship is on fire is no time to question the authority or discretion of the Captain. I am determined to move from Kentucky to Foreign parts all disturbing elements. Let the blows fall where they may. Longer forbearance would be criminal.

W T Sherman

Maj. Genl.

On August 31 Just over two weeks after writing this letter, Sherman launched a final, massive assault against Hood’s army, driving the overwhelmed Rebels out of the city. On September 2, 1864, Georgia’s most dreaded nightmare was now reality—William Tecumseh Sherman had captured Atlanta. The mayorana councilmembers implored Sherman, who had ordered all citizens (regardless of age or health) to evacuate the city, to be merciful. Sherman was unmoved. “You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will,” he scolded in a now-famous letter dated September 12;

Now that war comes to you, you feel very different. You deprecate its horrors, but did not feel them when you sent car-loads of soldiers and ammunition … into Kentucky & Tennessee, to desolate the homes of hundreds & thousands of good People who only asked to live in Peace …

Now you must go, and take with you the old and feeble, feed and nurse them, and build for them, in more quiet places, proper habitations to shield them against the weather until the mad passions of men cool down, and allow the Union and peace once more to settle over your old homes in Atlanta.

Sherman added a conciliatory note: “But, my dear sirs, when peace does come, you may call on me for any thing. Then will I share with you the last cracker, and watch with you to shield your homes and families against danger from every quarter.” (Sherman’s sentiments were not disingenuous; at war’s end he recommended such mild terms of peace that he was accused of treason by many in the North.) Writing to Silas Miller again, Sherman relates some lighthearted observations about Duke, his finicky but eventually accommodating horse, as the two rode victoriously into Atlanta.

Headquarters, Military Divison of the Misssissippi Atlanta Sept. 22, 1864

Silas Miller, Esq.

Dear Friend,

You have seen enough in all conscience and heard enough also to satisfy you that I made the riffle and got into this Forbidden City, and as I promised you I rode Duke in, that is the horse you gave me. I did so on purpose changing my saddle to him about 3 miles out.

Duke at first did not like this outdoor life & rough living—was particular about his meals, and city like would not drink water out of the creek or mud holes. The truth was he was a City Gent and looked on this out door life with contempt and was gradually showing the effect. But I have a most excellent fellow who humored him & gave him water in a bucket etc., & kept him along till the horse began to see that he was duly enlisted for the war and in for it when he began to mend. He is in fair order now and in perfect health and seems to like getting into town again, though he must observe that this is not Louisville.

Telegraph gives good news from Sheridan.—Next will be Grant, and then we must maul the wedge another bit and the log will split in due time. So thinks Old Abe the Rail Splitter.—I’ve got my wedge pretty deep and must look out that I don’t get my fingers pinched.

Audenried goes up with my dispatches and can tell you every thing. I have the place pretty well cleaned out, & regulated. And the People of Georgia see we are in earnest and won’t let trifles stop us.—I have forbidden all citizens to come, but as you may have an “irrepressible” desire to come I send you a Pass, and you may explain the exception on the grounds of belonging to the Christian Commission.

Yr Friend,

W.T. Sherman

Maj Gen

The news of Sherman’s conquest injected a shot of energy into Abraham Lincoln’s foundering presidential campaign. Ulysses S. Grant, still entrenched at Petersburg against Robert E. Lee, fired a one-hundred-gun salute in Sherman’s honor (in the direction of Lee’s army, of course). Grant also approved Sherman’s proposed “march to the sea,” a 300-mile campaign of destruction across Georgia. After burning almost a third of Atlanta to the ground, Sherman headed east in the beginning of November with over 60,000 troops, who tore down, ripped up, ransacked, looted, hacked, smashed, and threatened almost everything in their path. On December 22 Sherman sent a telegram to a grateful (and, with considerable debt to Sherman, reelected) president: “His Excellency Prest. Lincoln—I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah.” South Carolina was next. “Here is where treason began,” one of Sherman’s men stated with rising fury, “and, by God, here is where it shall end!”