Ambulance Corps Driver George Ruckle Describes to His Family a Failed German Offensive and the Skills American Soldiers Brought to the Fight & Maj. Edward B. Cole Provides His Two Young Sons with a Lighthearted Account of His Experiences in France

By the fall of 1917 the Allies were in a state of alarm. A meager 86,000 U.S. troops were on the battlefields of France (three times that many British soldiers were lost in the third battle of Passchendaele alone), and it would be months before the vast majority of American forces were primed for combat. Vladimir Lenin’s Communist revolution, which had appealed especially to war-weary peasants, led to an armistice between Russia and Germany, releasing over one million German soldiers from the eastern front. The reinvigorated German army launched a massive assault in March 1918, and U.S. troops, although still relatively inexperienced, were thrust into battle to stave off an invasion of Paris. In late May and early June the Americans fought with distinction at Cantigny and Chateâu-Thierry on the Marne River, just fifty-six miles—well within range of Germany’s heavy artillery—east of the French capital. (An estimated one million Parisians fled the city during the spring.) George Ruckle, serving with the ambulance corps, reported back to his family in Dumont, New Jersey, on how American troops helped French and British forces blunt the German juggernaut.

Dear Father, Mother & brothers,

This is the first chance I have had to write to you in over a week. We have just come back from the front where our division took part in holding back the Germans in one of their biggest drives of the war. This is the first German offensive which failed to make any gains and our boys not only held them back but counter attacked in several places.

The offensive was started by the Germans with a terrific barrage which began at 12.05 Monday morning and the French say it was the most intense since the beginning of the war. It was a creeping barrage and in some places the ground looked as if it had been plowed up, it was so full of shell holes and then all roads for a distance of 15 miles back were continually shelled.

When the barrage started there were 2 lieutenants and 5 of us men with three ambulances stationed in an abandoned village right behind the second line of defense and when the first shells began to come over we retired to a cellar that was about four feet high and crouched there waiting for a call. The first call came at 2 o’clock and Lauber and I started out for the ambulance which was parked in the yard back of the cellar in which we were. Just as we stepped out a shell whistled by and we ducked back in the cellar.

We tried a second time and got out allright and the sight that met our eyes was awe inspiring. The whole sky was a bright red and in three or four places where ammunitions dumps were burning, the flames were leaping into the air while here and there in the village houses were burning. The din was terrible, thousands of big guns were going off so rapidly that it made one continual roar punctured now and then by one mightier than the rest when an ammunition dump went up.

The road we rode along was lit up as bright as day and we reached the first aid station safely, being the first ambulance to reach that section. The wounded had just begun to arrive so we filled up our ambulance and started back for the hospital.

The bombardment kept up all that day and the next night and we ran continually for 48 hours with practically nothing to eat, but then everyone was so busy and our nerves were at such a high tension that we weren’t hungry.

I’ll never forget some of the sights I saw and how bravely our men and the French bore their wounds. Men with arms and legs torn off would never utter a groan during the whole trip to the hospital. At one place some new batteries came up and their horses were picketed in a clump of trees. I saw a shell land in the middle of them and the next minute there was a pile of 50 or 60 dead horses. The roads too were littered with dead horses and mules and overturned kitchens and supply wagons.

But as heavy as the German barrage was our boys held firm and our artillery sent back two for every one that came over. German prisoners said our artillery did horrible execution among their line troops and we know they were piled high in “no man’s land.”

One of our batteries that uses the French 75’s, a three inch shell, was sending them over so fast that a captured German asked to see our 3 inch machine gun.

The French say they never saw such wonderful work as done by our boys and the whole division got a citation from the French General in command of this section.

The Germans call us barbarians, they don’t like the way we fight. When the boys go over the top or make raids they generally throw away their rifles and go to it with trench knives, sawed off shot guns, bare fists and hand grenades, and the Bosch doesn’t like that kind of fighting. The boys from Alabama are particularly expert with knives and they usually go over hollering like fiends—so I don’t blame the Germans for being afraid of them.

At hand to hand fighting the Bosch is no match for our boys and any American soldier will tell you he can lick any two Dutchmen. Where the Germans shine is with their artillery and air service.

We captured a large number of prisoners, I don’t know just how many but it must have been a large number. Whole squads would come over and give themselves up and at one place a squad of machine gunners were captured and offered to turn their guns on their own men, but the American Lieutenant in command of the Americans who captured them wouldn’t allow it.

We carried a number of German wounded and everywhere they got the same treatment as the French or our own men. At one dugout they had an unwounded prisoner, a young boy about 17, and he helped us load the wounded in the ambulance and tried in every way to help do something. He was a nice looking young fellow and I couldn’t help liking him.

All of the prisoners were well equipped and each man had a map of the territory they were supposed to have taken in the drive. Most of them said they were glad they were captured and that Germany would soon have to give in, but a few were defiant and one of them said it didn’t make any difference how many Americans were over here, Germany would whip them all. One wounded German kept crying out in the ambulance that was taking him to the hospital saying, “Mein Goot, Mein Kaiser.”

Well, I guess I’ve written enough about the fight so will talk about something else.

I found a bunch of letters waiting for me when I got back last night and haven’t had time to read them all yet. I read the latest one from home to see if everything was OK and was relieved to find it was.

So Jamesie was expected to sail July 6th. If he did he is over here by now and I might get a chance to see him soon. All the boys you know including Elliot and Lauber came through safe and are well.

I will close now hoping this finds you all well,

With love to all,

George

Almost immediately after the U.S. army’s triumph at Chateâu-Thierry, a brigade of marines with the Second Division attacked fortified German positions on June 6 just west of the town in Belleau Wood. Outnumbered, gassed, and raked by machine-gun fire, the marines were nearly overwhelmed. When retreating French troops advised the Americans to do the same, Capt. Lloyd Williams barked, “Retreat? Hell, we just got here.” Resorting to hand-to-hand combat, they tenaciously fought back and prevailed over the Germans on June 26. But their losses were staggering; the marines suffered approximately 5,200 casualties, almost half of their strength. One of those wounded was Edward B. Cole, a Marine Corps major who left behind his wife, Mary, and two young sons, Charlie (age ten) and Teddy (age eight) to serve in France. Cole frequently wrote to his family back in Brookline, Massachusetts, to give them updates on his well-being and general whereabouts, and, six weeks before the attack at Belleau Wood, Cole sent his boys the following letter. (“Prince” is Cole’s horse.)

April 22nd, 1918

Dear Charlie and Teddy:

I have received several very nice letters from you both. What a time you did have with the measles, did you not? Well the time to have them is when you are young so you will not catch them when you get older. Prince is quite well and sends his love to you both, he says that when we get back to the United States that he will be very happy to let you ride him provided that you feed him regularly with sugar. He and I went to the front line trenches the other day at least Prince went part way, but just now we are back in our headquarters.

A short time ago Capt. Curtis and I were in our mess room eating breakfast when ‘Blooie’ went a big shell just outside the window. I got a piece of toast mixed with a swallow of coffee in the wrong channel of my throat and Capt. Curtis, well the last I saw of him he was easily outrunning a 9.2 shell in the direction of the dugout. Somehow I caught up with him at the entrance and we passed in neck and neck for a dead heat. It ain’t no disgrace to run when you are skeered. These 9.2 shells are almost as tall as Teddy. How would you like to shoot one in your air gun. Where I am writing this letter is behind the lines and the Bosche have only shelled us once but a dugout entrance leads into my office so you can see I resemble a prairie dog sitting in front of its burrow ready to duck in if danger comes its way.

We see lots of airplanes here it reminds one of Pensacola except that when it is a German plane our anti aircraft guns fire at them. They do not hit many, but they keep them high and away. The Germans have lots of balloons in the air like the one you boys and mother went up in while we were at Pensacola. The French have a lot of them also. Where I sleep is a little three room cabin or hut that you would like to own for it would be just the thing for boy scouts. At night we have to darken all the windows so the lights will not show—that is to prevent the German airplanes from interrupting our sleep with bombs. I do not think you would like that part of the hut life quite so well, do you?

Yesterday I saw a mule that had been killed by shrapnel fire. The French had skinned him and were cutting him up to eat. The meat looked rather tough to me but I do not see any reason why it should not be wholesome so some day when I get a chance I shall try a mule sirloin. I wonder if it will be as good as that pole cat stew. Good gravy! My men got a few helmuts the other day but had to turn them in so I can’t send you one. Anyway they were not the right kind as they had no spikes on top. Now I know you boys have no yellow streak because you are doing better in school and I am always so proud of you when you do well and when mother writes me that you are not doing well in your studies it makes me very unhappy so if you want to help your old dad away over here—away from you and who is fighting for you just study hard and do your best in school.

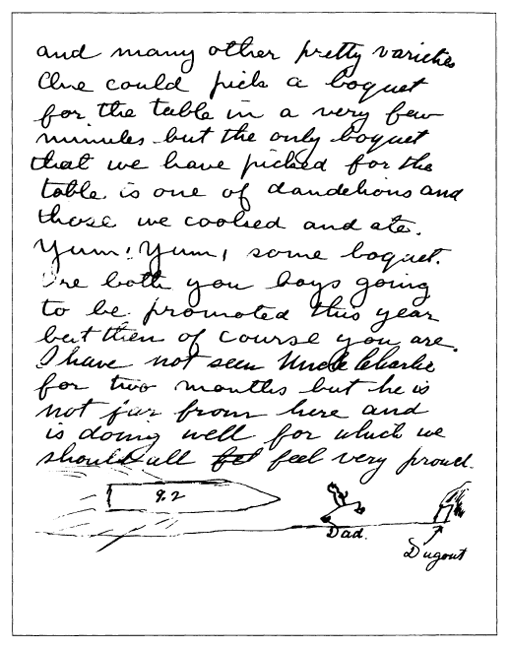

The woods here are full of wild flowers, violets and many other pretty varieties. One could pick a boquet for the table in a very few minutes but the only boquet that we have picked for the table is one of dandelions and those we cooked and ate. Yum! Yum! some boquet. Are both you boys going to be promoted this year but then of course you are. I have not seen Uncle Charlie for two months but he is not far from here and is doing well for which we should all fel feel very proud.

How do you like the picture of your dad, dug out and the little accelerator behind him. One thing over here the more rank one has the better dug out, sometimes that makes me wish I were president.

Now I must close but I want you both to do something for me. Go to mother, put both your arms around her neck and give her a kiss for dad and tell her that although dad scolds her sometimes in his letters and is pretty much of an old grouch, he loves her with all his heart and the poetry she sent him about the ship sailing over the sea is very beautiful and she was a darling to send it. Now boys be good and take care of the only girl in our family.

Dad

On June 13, one week after the marines launched their attack at Belleau Wood, Mary Cole received a letter from her brother-in-law, Brig. Gen. Charles H. Cole, stating that her husband had been wounded in both arms, both legs, and on his face after a grenade exploded directly in front of him. “Luckily for him,” Gen. Charles Cole wrote after visiting his brother in the hospital, “his eyes were not hit, (something miraculous). Today the doctor told us that, unless something unforeseen happens, he ought to survive. Tell Charlie and Teddy there is no braver man in the American Army than their daddy.” Something unforeseen happened two days later; severe blood poisoning spread rapidly throughout Cole’s system and, despite two amputations to stem the advance of the infection, Maj. Edward B. Cole died on June 18. In October 1918 the United States Navy christened destroyer no. 155 the USS Cole in his memory.