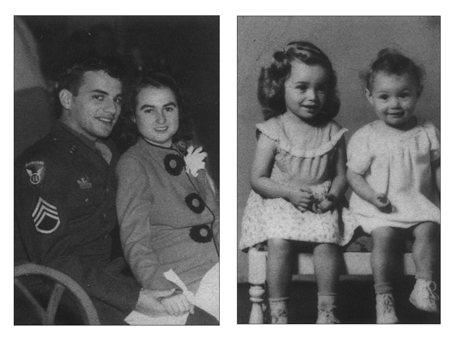

A highly decorated veteran of World War II, Joe Sammarco was twenty-four years old and attending airline management school in Kansas City, Missouri, when the fighting in Korea erupted. Sammarco, who had experienced combat with the Eleventh Airborne Division during the ferocious invasion of the Philippines, had no intention of serving in another war. But when a Kansas City newspaper published a photograph of kneeling, blindfolded American GIs being executed with a pistol shot to the head by Chinese soldiers, Sammarco was so enraged he enlisted immediately. After a brief retraining at Fort Hood, Texas, in the fall of 1950, Sammarco left behind his wife, Bobbie, and two young daughters, Grade (age three) and Toni (age one), in Midland City, Alabama. On November 20, the day before he was to pass once again underneath San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge on a ship bound for Asia, Sammarco wrote the following to his wife.

My Darling Bobbie,

Well, tomorrow at noon I will be on my way. Bobbie darling, it is going to get so very lonesome for me now. Going farther away from you is going to hurt so much. But it won’t be for long sweetheart. And then there will be no more of this running around all over this world. Just promise me honey, that you will continue to take such wonderful care of our babies! And above all honey, don’t let them forget me.

Don’t worry about me sweetheart, I have no ideas about becoming a dead hero! At the same time, I don’t think there is a chinaman in Korea that can give me too much trouble. I’ve got some good equipment this time, and I think I know how to use it pretty well. Just don’t you worry too much, and be sure and write often as soon as I give you an address to write to. And Bobbie, be sure and say your prayers every nite, and see that Gracie says hers also, and say some for Toni too.

I love you my darling, forever, with all my heart. Just keep loving me, won’t you honey? That’s all I want sweetheart.

Well, I’ve got to go and get some copies of my orders and finish packing. Good nite my darling.

I’ll write again from California, Mon. or Tue.

I love you, so very much Bobbie, and I will always love you my darling.

Joey

“I was going to write last nite, but my ink was frozen in the pen,” Staff Sergeant Sammarco wrote to Bobbie two days before Christmas 1950 from an abandoned schoolhouse WO miles southeast of Inchon. Thrust into battle with the Second Infantry Division soon after his arrival, Sammarco was quickly discovering how intolerable winter in Korea could be. “Honey, this is really rough. I have been so cold & hungry for so long I think I am getting used to it. Haven’t heard from you since I left the states, but we are not getting but a very few letters here. Bobbie, don’t let anybody kid you, we are really losing men, by the thousands.” Attached to a French battalion as a forward observer and liaison sergeant from the Thirty-seventh Field Artillery Battalion, Sammarco encountered the full savagery of the war less than two months later in Chipyong-ni. Four divisions of Chinese and North Korean troops unleashed a five-day blizzard of mortar, machine-gun, and shell fire on the town beginning on February 12, 1951. Although airdrops replenished food and supply shortages, ammunition constantly ran low, and at one point the UN soldiers resorted to bayonet charges and hand-to-hand combat. But despite the lack of firepower and a casualty count that numbered in the thousands, the surrounded UN troops repelled the Communist forces. In a letter to his wife dated February 22, Sammarco offered a firsthand account of what he had endured.

Bobbie Darling,

Sorry I haven’t written, but I have not been able to! If you heard the news, maybe you heard about the French & Americans that were trapped in the town of “Chipyong.” Well, I was one of them. It was a nitemare that lasted for 5 days & nites. We were completely cut off and surrounded with no food and very little ammunition. There were 4 divisions of Chinese around us, and the last two nites they broke through our lines and we were fighting hand to hand in the streets & houses, (what was left of the houses.)

Bobbie, you will never know how lucky I am to be alive. I was on my switchboard when they broke into the house, and at first I was too scared to move. Then they killed my Buddy (Johnny) and I got over being scared. I don’t know what happened after that except that as the sun started to come up there were several hundred dead & wounded Chinese all over the place and they retreated (what was left of them) back to the hills. We had about 200 Americans killed, twice that many wounded, and I don’t know about the French. My Battery Commander, my 1st Sgt., 3 wire Sgts, and several of my buddies were killed & wounded. Several times I thought it was all over for me, but I was lucky. Right now I am still with the French down in the Wonju area. I hope it will be over soon. I love you so much, and I must get home to see you again. I am all right now honey, and I think it will be quiet here for a little while, anyway. Please keep writing, and remember how very much I love you & miss you,

Kiss the babies for me,

I love you,

Joey

For his “magnificent example of courage” demonstrated during the battle at Chipyong-ni Staff Sergeant Sammarco became one of few Americans ever awarded France’s croix de guerre with the Silver Star. As part of the UN drive pushing north toward the Thirty-eighth Parallel in early 1951, Sammarco was caught in one skirmish after another. “Honey, I’ve had a couple of close calls, too close, but I’ve been very lucky,” he wrote on February 29. “I’ve seen my best friends blown all to pieces, I’ve been less than 1 foot from fellas that have never moved again, and it’s right at those times when I think of you, and wonder if you are thinking of me.” Sammarco frequently expressed how worried he was about Bobbie and his little girls, and on March 1 he asked Bobbie to assure him all was well back home. (Like many of his comrades, Sammarco often referred mockingly to the war in his letters as a “police action”—the term used by the Truman Administration and the UN to describe the fighting in Korea. Despite the Constitutional imperative, President Truman never requested a formal declaration of war from Congress.)

My Darling Bobbie,

I got a letter and a birthday card from you to-day. And it sure was wonderful hearing from you. But you also told me that Toni had a sore mouth & Gracie was sick also. That worries me very much, but I know that you will take good care of our babes. Please tell me if you are getting enough money! And if you are getting the things you need.

We have been moving right on up without too much trouble, but the Chinese seem to be massing for a big, and final attack. It doesn’t look good, but I just know it is coming. After the next big ATTACK, (which is predicted to be the biggest of the “Police Action”, (ha! ha!) I think the Chinese will be about washed up, if they don’t get the best of us. I guess it will really be a bloody mess.

Incidently, in that article with this letter, I happen to know what happened to that chink field officer, and I’ve got the proof right here in my pocket. I also snapped a picture of him. I went with the French just before we got trapped at Chipyong, and am still with them.

I sure hope that it will all be over soon, I am sick of this whole mess over here, and if I stay too long, I’m just liable to get hurt, but I’m not worried about that.

Are the babies any better now? I just pray so much that you all are all right. Does Gracie even mention me anymore? I hope so. I know that Toni doesn’t even know who or what I am, but when I get home we will make out all right. Please tell me more about the babes, and honey, please tell me all about you and what you are doing and how you are feeling. I love you so much honey, and if I don’t seem to tell you often enough it is only because I don’t have the time, paper & pencil all at the right time. But you must know how very much I love you, I just worry sometimes that you may grow tired & weary of waiting & waiting. I hope that someday I can make it all up to you,—maybe I won’t get the chance, but if I do I will always love just you sweetheart. Well, I’ve got to get my rifle cleaned & my knife sharpened up. Where we are now it doesn’t pay to have your weapon apart many minutes. These nites sure are getting on my nerves. Well, it’s getting dark, so I must get going,

Good nite Sweetheart,

I love you with all my heart,

forever,

Joey

On March 7 UN forces launched Operation Ripper, a massive initiative to regain the Thirty-eighth Parallel. As Sammarco feared, he was right in the middle of it.

Mar. 16, ’51.

My Darling Bobbie,

Well honey, I guess the lord is working overtime for me lately. Yesterday afternoon I got the purple heart. But I am all right, so don’t you worry about me. I was about 10 yds. behind the red panel that shows the end of friendly territory. I was relaying fire missions on my radio. All of a sudden a Chink mortar came in. It hit my Captain & killed my radio operator. My Capt. started walking towards me holding his chest, and I was lying on my stomach looking up at him. Just before he got to me another mortar hit just about a yard to my left on the road. It lifted me about a foot off the road and I got a piece in my leg & another piece in my arm. But please believe me, I’m O.K., just a little nervous.

What kept me from being killed Bobbie, I will never know. Maybe I was too close to the explosion and the stuff flew over my head, I don’t know, but anyway, after it went off I couldn’t find my Capt. so I went back down the road, fast, about 100 yds, and just sat there in a ditch waiting, for nothing. Then I saw the blood coming through my sleeve & my pants, but I knew it couldn’t be too much or I wouldn’t still be sitting up. So, I stopped a medic and he sent me back & now I am all right & don’t you worry. And if you happen to get a wire saying I am wounded, disregard it, cause honey, ah is all rite!!!

Honey, I got another letter from you this morning, and it sure came at the right time. But honey, you must stop worrying, I’ll be all right. It just isn’t my time to go, and I just know that I will get back all right. And Bobbie, this stuff is getting old, and if I’m not worried, sure you can stop worrying. I’ll be all right. But you will be sick if you don’t stop worrying. I love you honey, and nothing will keep me from you, ever. Bye for now, and promise me you will stop worrying.

I Love You—Joey

After receiving only basic first aid to treat shrapnel wounds to the leg and arm, Sammarco was back in combat. By the beginning of April 1951 the UN forces were on the offensive and crossing over the Thirty-eighth Parallel into the North. (President Truman hoped to seize the opportunity and begin peace negotiations—until General MacArthur undermined them with his belligerent ultimatums to the Chinese and was dismissed by Truman on April 10.) Weeks passed before Bobbie heard from her husband again. “Sorry I haven’t written for so long,” Sammarco explained in a short note dated April 14, “but I haven’t had a chance, and I have been so far up in the mountains that I could not have mailed a letter anyway.” A week later Sammarco was able to send another letter during a lull in the fighting.

Apr 21, 51

Bobbie Darling,

Just a few lines to say hello & to tell you I love you. I have been back here at the Bn. for 2 days now getting a little rest, and thought I would have a couple more days, but, to-nite around midnite I will be on my way back up to the front, about 12 miles. It sure feels good to get back this far once in a while where you can sleep all nite long and close both your eyes. But then I am not doing any good when I am way back here.

One of my buddies got killed this morning. They just brought him in a few minutes ago. Last week he told me if anything ever happened to him for me to write his wife and send some of his pictures on home. Well, I just don’t feel like it and I think it would be better if I didn’t write. He has a boy, 3, and a little girl, 1, and when I think about it I get so nervous I don’t know what to do. Anyway, I can’t write.

This afternoon I took a walk down to the river and that is where I found the violet I enclosed. It was so peaceful & quiet down there and its just like spring anywhere in the world. That clipping was in Readers Digest, and it reminded me so much of Gracie that I thought you might like to read it also.

I may not be able to write for a few days now, but don’t worry, I will be all right.

I don’t know when I will be able to come home, but it should be in the next 3–4 months at the latest. Unless, of course, the “Police Action” (HA! HA!) takes a turn for the worst, which it might easily do.

Well, I’ll have to sign off for now, and besides, I have a bad headache.

Bye for now,

I Love You,

Joey

P.S. Please kiss Gracie and Toni for me, I love you, Joey

The very next day the Chinese army hurled itself at the encroaching UN forces, which withdrew almost entirely into South Korea in less than a week’s time. The war had become a human tide of troop movements ebbing and flowing across the Thirty-eighth Parallel with no end to the fighting in sight. In the middle of May the Communists—who outnumbered the Americans and their allies three to two—hit again, hard. Throughout the war the Chinese frequently struck at night and began their raids by banging drums, shrieking at the top of their voices, and blowing bugles and whistles. Originally it was believed they did this only to scare the wits out of the enemy (which it did), but, lacking in radio communication, the Chinese were also signaling fellow units. Sammarco alluded to the unnerving tactic in a letter dated May 12: “The Chinks are coming in again and we can hear them. I will not sleep I guess. But then I have such nightmares when I do sleep I guess it does not make much difference if I sleep or not. Every nite the darkness gets a little worse for me.” Daytime proved even more frightening for soldiers who traveled in the UN convoys that snaked their way through the narrow valley roads of Korea. Hidden Chinese snipers shot the drivers in the first vehicles, and then, as the UN soldiers fled from their trapped jeeps and trucks, Chinese machine-gunners and artillerymen opened up on them from all sides. In a letter dated May 28, Sammarco mentioned an ambush he barely escaped:

Well, I am still pretty lucky. We were cut off and trapped again the other day, and had to try and run through a Chinese roadblock. It was at the town of “CHAUN-NI.” … My ¾ ton truck got machine-gunned before I went ½ mi. down the road. It wounded my Captain, & killed my other two men. I fell off the truck & was hit & crawled down into the creek. The Chinks had all the high ground along the road and I watched them come down from the hills like flies & kill our men & take a lot of my buddies prisoner. And I just about gave up too, but I couldn’t do it. I worked my way down the stream a ways and then up into the hills. I kept crawling until I didn’t think I could go any further, then I would think about you & the babies, and go on some more. I guess I am pretty lucky to have you praying for me so much…. [W]hen we got back to Chaun-ni it was the worst thing I’ve ever seen. All the vehicles were shot up & burned & the place had hundreds of dead all over. Dead G. I.’s all over. After we got out of Chaun-ni the Air Corps & our big guns just about blew that place off the map. There were pieces of “meat” hanging from the tree-tops.

Despite initial defeats, the UN forces rallied and set in motion a major counterattack. On May 30 Sammarco wrote: “Well, we are pushing ahead, after our latest ‘strategic’ withdrawal!! We are killing many many Chinese,—but of course we are losing men also.” Sammarco survived the sweeping UN assault, which inflicted catastrophic losses on the Communists in late May and early June 1951. In July both sides called for peace negotiations, which was especially welcome news to Korea’s civilian population, ravaged by almost a year of war. (The first round of peace talks would unravel a month later.) Sammarco was devastated by the suffering he saw among Korean families and children, and he often wrote to his wife about their plight. In a letter concerning mostly routine financial matters, Sammarco added the following:

It all seems so futile sometimes, this waiting & crawling around like an animal nite & day. But it must end soon, because I have just got to see you & be with you again before long. After this mess over here I don’t know how I can ever get over it. Everybody is so unhappy everywhere I look. And it seems that there is absolutely no future for all these sick & weary people. Even if the war did end, there is no place for anybody to go. No homes, no food, and for thousands of kids, there are no parents. I wish I could bring one of them home with me. If there was a way, would you want me to bring one with me? I found one yesterday in a house, sitting on the floor crying her little heart out. Everybody else was dead…. [W]hen you see it nite & day, week after week & months on end it just gets to you. You cannot even conceive of the situation as it actually is. But I am glad you don’t have to see it.

Although they would both later realize the many complications involved with trying to adopt a Korean child, Bobbie was not opposed to the idea. Sammarco was confronted with an even more terrifying incident involving Korean children on June 11, 1951, which he described in graphic detail that night.

My Darling Bobbie,

Here I am again to say hello and to thank you very much for the sweet Fathers Day card which I received today. It is so nice honey, and I was happy to get it.

Well, in a couple of days I am supposed to receive a medal and citation from the French Government. I don’t know just what it is, but I was told that it is in connection with Chip-Yong-Ni, but at any rate I will let you know more about it in a few days. Also I was told today that I am to receive the American Bronze Star medal for action at Chaun-ni a couple of weeks ago. One more thing, I am now back in the rear area of the division for a while. I was sent back a couple of days ago. It seems that they think that I need a little rest, which suits me fine.

As I told you before I have not been sleeping too good lately, and the other nite I came close to shooting one of the Korean guards for a Chink. It’s just that my nerves are a little worn, and I know that a few days back here will do a lot of good. Now don’t you go and worry about me, because I am perfectly all right, believe me. It is not unusual for a man to be sent back here for a few days to rest, in fact there are a couple of other boys here from the outfit with me. We can sleep all we want back here, eat good, and see a few movies and drink a few beers, and that should certainly get me in good shape, but quick. And it also gives me more time to think about you and the babies.

I am glad that you feel as you do about my bringing home one of these little Koreans if it is possible to do so. Even if I can not do it, I appreciate your feelings concerning these people. It is such a very sad picture, and the more that I see of it, the more I feel that any little thing that I might do to alleviate the situation is completely worth the time, trouble, and money it might take to do so. I have not had the time to look into it very thoroughly yet, but I hope that I will have the time before I leave here.

Bobbie, please keep a close eye on the babies all the time for me, and I mean just as much as you can. I saw two little kids get run over and killed today, in less than two hours. It makes me sweat just to think about it, it was the most horrible thing I have seen yet. In the first one it was a little girl that was run over, by a jeep. The jeep was coming towards me, the little girl ran right in front of it. It knocked her down, ran over her, caught her under the jeep, dragged her a ways, and when he tried to stop he just ran right over her little head. I have seen some pretty dirty things over here, but those two incidents today were the worst. I stopped my truck, and for a few minutes I just couldn’t believe that it had happened. I kept thinking about it and as I started to leave Wonju to head back here the little boy got hit. And it was even worse, but I won’t go into that one too, it’s not very nice.

What I am driving at is that I immediately thought about our babies, and Honey, I worry so much about them. I know you take wonderful care of them, but I just can’t stand to think about even the smallest little thing happening to either of our babies. Please sweetheart, be so very, very careful with them, and with yourself too darling. I love you all so much sweetheart, and just have to stay well all the time. So please Bobbie, promise me now that you will be especially careful all the time, and watch the babes real close, especially during this hot weather, and watch out for snakes and bugs and anything else that might hurt you all in any way.

Well, I guess that that is all for this time honey, but I will write again real soon, and thanks again sweetheart for that very sweet card. I have your pictures out right here next to me now, and honey I miss you all so much. I would give so much to be able to be with you right now, to hold you and love you so much the way I want to. But honey, don’t you worry, I will make it all up to you just as soon as I can get my arms around you again.

Good Nite my Darling,

I Love You So Very Much,

I Love You Sweetheart,

With All My Heart & Soul,

Joey

Wounded three months earlier in the right arm (which still had shrapnel in it) and left leg, Sammarco had an aggravated limp which was becoming increasingly painful. In mid-June his superiors ordered him to the army hospital in Osaka, Japan. After a successful operation on his leg, Sammarco was sent home to his wife and children in January 1952. But his stay was short-lived. Months later, after pursuing a job with the State Department, Sammarco headed to Taiwan to work for an import/export company named Western Enterprises, Inc. In fact, the company was, according to Sammarco, a CIA front; Sammarco’s real assignment was on the island of Tachen, only a few miles off the coast of mainland China, where he trained former prisoners of war captured in Korea to subvert China’s Communist dictatorship. (When Mao Zedong’s revolutionaries overran the U.S.-backed regime of Chiang Kai-Shek in 1949, Chiang and what remained of his Nationalist government fled to Taiwan.) The POWs Sammarco was training in Tachen were the very same young Chinese men he had been trying to kill, and who had been trying to kill him, in Korea. After a year in the region and approximately three months in Saipan, Joe Sammarco was on his way home for good. Still a young man (he was only twenty-eight) he settled into a long—and refreshingly calm and quiet—career in the automobile and truck business.