Pvt. Brice E. Gross Offers His Younger Brother, Jerry, Words of Advice and Encouragement After the Death of Their Father & In a Letter to His Wife Joyce, 1st Lt. Dean Allen Reflects on the Physical and Emotional Challenges of Leading a Platoon

By the end of 1967 the number of American troops in Vietnam was nearing the five hundred thousand mark, a 5,000 percent increase since late 1962. Approximately 3 million sons, husbands, brothers, and fathers would ultimately pack up and head out for Southeast Asia throughout the course of the war. (An estimated 10,000 women served in Vietnam as well, primarily as army, navy, and air force nurses.) For twenty-year-old Brice E. Gross, a private with the U.S. Army, saying goodbye was especially difficult because his father had died from a heart attack months before he was shipped overseas, leaving his thirteen-year-old brother Jerry to be—in Gross’s words—“the man of the house.” Just over halfway through his tour of duty, Gross (who would return home alive) wrote to his brother back in Fresno, California.

Hello Jerry, how is my “big” little brother? I trust you’re doing good and keeping yourself out of trouble. I figured I’d write you a special letter because if I was home, we would have had some serious brother-to-brother talks, but I guess a letter will have to do.

Well, to get down to business, I’ve been doing a lot of thinking and wondering about how things are going back at home. You well know by now that you’re taking Dad’s and my place in the family now that I can’t be there and for such a young man you’ve got quite a load to bear. I may just be repeating what other folks have told you, but I believe you’ll understand it as my duty. You’re going to have to sacrifice a little to keep things going smoothly around the house now. All the things that our Dad or me or all of us did before, are now your responsibility. It’s quite a task to undertake, but I’m confident you can do it. Now that you’re out of school for the summer and ready to be off, you’ll have to curb your wandering spirit a little for the sake of your Mother. Before you do something, consider carefully the consequences of your actions. I know it’s a lot to ask, but you’re going to have to spend an equal amount of time at home with Mom as you do out on your own. Remember, you’re filling Dad’s shoes, and he was the best husband any woman ever had. Mom and Dad have devoted the last 25 years of their lives to raising us kids, and now our time has come to repay them for at least some of their love and care.

You know well now that you are by no means a “kid” any longer even though you are still young. Try your best to keep yourself straight and be especially kind to Mom, because for a while you’re going to be her only son. Treat her to a movie now & then, buy her a flower or some candy, use your imagination and think of your own special ways to make her day a little brighter. Remember—she’s the only Mother we’ve got, so take good care of her.

You can see that I worry a bit about you & mom, but I have a lot of trust in you Jerry. Not many people are lucky enough to have a brother like you. And once in a while, take time out for yourself and maybe ride out somewhere alone on your bike & think things over & consider that even though we’ve lost a lot, we still have a great deal to be thankful and happy for.

Before I left for Vietnam, Dad said something to me and these were the last words I ever heard from him. He said, “Be a Man.” You and I both know what that means, and I want to repeat the same admonition to you. If ever you are in doubt, think of your Dad and those words and you can’t go wrong.

Bye Jerry & be good.

Your Brother

Brice

Young couples separated by the war also turned to letters to share words of support, love, and reassurance during their time apart. Dean Allen, who had been married for only two years, was ordered to Vietnam after attending officers’ training school. Although externally he seemed like an imposing, no-nonsense leader, First Lieutenant Allen was, in fact, a compassionate, thoughtful twenty-seven-year-old who had a genuine concern for the men in his platoon. In the following letter to his wife, Joyce, in Pompano Beach, Florida, he confided in her the feelings and insecurities he could not express to anyone else.

July 10

Dearest Wife,

There are many times while I am out in the field that I really feel the need to talk to you. Not so much about us but what I have on my mind. I can tell you that I love you and how much I miss you in a letter & I know you will receive it and know what I mean, because you have the same feelings.

But many times like tonight—I am out on ambush with eleven men & a medic—after everything is set up and in position I have nothing to do but lay there and think—why I am here as well as all the men in my platoon—age makes no difference—there are very few kids over here—a few yes but they grow up fast or get killed. Why I have to watch a man die or get wounded—why I have to be the one to tell some one to do something that may get him blown away—have I done everything I can do to make sure we can’t get hit by surprise—are we really covered from all directions—how many men should I let sleep at a time, 1/4, 50% or what. I know I want at least 50% awake and yet those are the same men who have to hump through the jungle the next day carrying fifty to seventy five pounds on their back and still be alert and quick if they run into Charles the next day. If I have four or five man positions, and only have one man awake per position they like me because they get some sleep. If I have them in two man positions and have one man awake they bitch and moan & aren’t worth a damn the next day. If I don’t we may all get our shit blown away—excuse the language but that’s what they call it over here.

Babes, I don’t know what the answer is. Being a good platoon leader is a lonely job. I don’t want to really get to know anybody over here because it would be bad enough to lose a man—I damn sure don’t want to lose a friend. I haven’t even had one of my men wounded yet let alone killed but that is to much to even hope for to go like that. But as hard as I try not to get involved with my men I still can’t help liking them and getting close to a few. I get to know their wives name or their girls and kids if they have any They come up and say “hey 26 (they call me 26 because that is my call sign on the radio) do you want to see picture of my wife/girl” or “look at what my wife or girl wrote.” Like I said it gets lonely trying to stay seperate.

Some letter, huh! I don’t know if I have one sentence in the whole thing. I just started writing.

July 11

It got so dark I had to stop last night it got to dark and rained for twelve hours straight. Writing like that doesn’t really do that much good because you aren’t here to answer me or discuss something. I guess it helps a little though because you are the only one I would say these things to. Maybe sometime I’ll even try to tell you how scared I have been or am now. There is nothing I can do about it but wait for another day to start & finish. If I had prayed before or was religious enough to feel like I should—or had the right to pray now I probably would say one every night that I will see the sun again the next morning & will get back home to you. Sometimes I really wonder how I will make it. My luck is running way to good right now. I just hope it lasts.

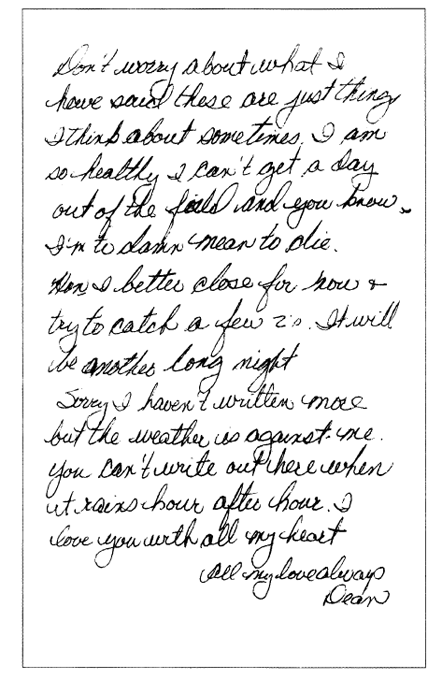

I have already written things I had never planned to write because I don’t want you to worry about me anyway. Don’t worry about what I have said these are just things I think about sometimes. I am so healthy I can’t get a day out of the field and you know I’m to damn mean to die. Hon, I better close for now & try to catch a few z’s. It will be another long night.

Sorry I haven’t written more but the weather is against me. You can’t write out here when it rains hour after hour. I love you with all my heart.

All my love always

Dean

Soon after receiving Dean’s letter, a telegram arrived from the war department. Joyce Allen could barely get past the first sentence.

The Secretary of the Army has asked me to express his deep regret that your son, Lieutenant Dean D. Allen was wounded in action … He received multiple wounds to the brain, the left eye, the face, the chest, the abdomen, both arms and both legs. He has lost his left eye and is in a deep coma. He has been placed on the very seriously ill list and in the judgement of the attending physician his condition is of such severity that there is cause for concern….

Clearly, Joyce thought, there had been a mistake. Dean was her husband, not her son, and his middle initial was “B,” not “D.” But despite the errors in the message, it was, in fact, her Dean who had been fatally wounded. Four days after writing to Joyce, Dean stepped on a land mine while on a search-and-destroy mission. As he was being evacuated, a second mine exploded. 1st Lt. Dean Allen, a recipient of the Bronze Star, Air Medal, and Purple Heart, died three days later.