Capt. Samuel G. Putnam III Chronicles for His Wife and Family His Participation in the Ground War & S. Sgt. Dan Welch Reflects in a Letter Home How Strange the War Seemed and Expresses His Regrets the Allies “Didn’t Go Far Enough”

After being pounded from the air for almost six weeks, Saddam Hussein’s forces were badly crippled but not defeated. Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf and his commanders were anxious to end the war but agonized over how and when to begin the ground campaign. They estimated that Hussein had four hundred thousand troops, including his highly trained Republican Guard, entrenched throughout the mine-strewn deserts of Iraq and Kuwait. They also feared that, if cornered, Hussein might use chemical weapons. It was possible that up to ten thousand Americans, maybe twice that number, would die in the offensive. But President Bush believed the time had come, and the order was given: The ground assault would begin on Sunday, February 24. On her last mission ever, the USS Missouri—upon whose decks the Japanese officially surrendered in 1945—bombarded Kuwait’s beaches on the evening of February 23, suggesting that an amphibious attack would follow. In fact, it was a feint. The real invasion came hours later as the U.S. Marines charged straight into Kuwait from Saudi Arabia. Hundreds of miles to the west, Allied airborne troops headed north and then swooped east toward Kuwait in a flanking maneuver. The army Seventh Corps, with its heavy armor, would follow a similar hook pattern in the west to cut off Iraqi troops from all directions and ultimately crush the elite Republican Guard. President Bush was attending church services and had no idea how the operation was unfolding. Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney received the first reports from the field and passed a handwritten note up the aisle that read simply:

Norm says it’s going very well!

In fact, Schwarzkopf and his generals were stunned by what they were hearing: Saddam’s troops were surrendering in droves. Some did resist, and scattered firefights erupted. But after only one hundred hours, the ground campaign was over and the Allies were victorious. Thirty-one-year-old Capt. Samuel Grady Putnam III, a flight surgeon from Pennsylvania with the 1/1 Cavalry Squadron, 1st Armored Division, Seventh Corps, wrote to his wife back home the day the fighting stopped.

2/28/91

Dear Sharon,

It’s great to be here, even if this place is windy, dusty & ugly—it’s just great to be able to write a letter after the past 4 days.

We’re now in Southeastern Iraq, about 12 miles west of the Kuwait border. It was a truly incredible trip to this spot, which I’ll tell you about from the beginning.

On the 24th, at about 8 AM, we started moving north from our last holding area in Saudi Arabia. We’ve known for about 4 weeks what our mission was—to go into Iraq and outflank their forces, focusing in on the Republican Guards. So we headed north, thinking we’d stop just short of the border and spend the night. There was one unit ahead of us—the 2nd Armed Cavalry Regiment. Things were going so well for them, that we got the word we would go straight into Iraq that day. We stopped a couple miles south of the border, put on our chemical suits, took our PB tabs (anti-nerve agent tabs), and had a quick orders brief….

Periodically I tuned into the BBC news on shortwave—the press still didn’t seem to know that we were moving north. We thought this would be our first big battle day. We thought we’d be getting shot at as we moved north that day, but instead we ran into a bunch of surrendering Iraqi soldiers. The spot reports started slow, maybe 3 EPW’s (Enemy Prisoners of War), then 7, then 15, then 60, then 120 Iraqis surrendering. There were a bunch at a bunker complex that was targeted for artillary, so we had to get them out before our artillary could blast it. It stopped us for a couple hours, so I stood up on the aid station and watched the entire 1st Armored Division pull up behind us—it was incredible. Thousands of vehicles rolling across the desert. It visually showed me what a feat it was getting all this stuff here—and that just one Division out of the 8 that the army has here. A herd of camels got caught up in the movement and were totally perplexed—didn’t know which way to go.

Back to the EPW’s—they knew exactly how to surrender, thanks to the leaflets that our air force dropped on them. They had no desire to die for Saddam. I saw lines of them, hands over their heads, waving anything white that they could find. One guy was dancing with a white sheet over his head. One group had a dog surrendering with them. They looked pretty hurting—torn up uniforms, thin, many without shoes. They just left their weapons sitting on the ground. We picked up so many of them that we stopped stopping for them and just pointed them south—let someone else in the Division pick them up.

Our troops made a bit of contact with Iraqi troops not willing to give up—but they blew up the vehicles & took care of that. None of our guys were injured. The day ended about 70 miles into Iraq. It was raining and very dark and we were the furthest unit into Iraq—half of our soldiers were on guard that night. I slept in one of our ambulances and got a great 8 hours of sleep.

We knew the war was going well. We were moving faster than expected and had very few casualties, so for us it was going real well. We also heard the reports of how other fronts were doing and they were all good. The Republican Guards were moving southeast, just like we wanted them to. Our move was a flank/encircle maneuver to isolate them. I was happy to just follow along & hear what was happening, as long as we weren’t getting shot at and our squadron wasn’t getting casualties.

The next day we moved out at first light. The terrain changed dramatically—it was hilly with lots of small scraggly bushes and more camels. We went through a large bedouin camp. I wonder what they were thinking as this division rolled through the camp. Our air troops found a bunch of enemy tanks to our south, so we stopped for a couple hours while we worked with air force to take them out. I was still just following along, looking at my map once in a while, and hoping that the battle would continue to go as well.

By nightfall we were at our objective that was supposed to take 4 1/2 days to reach. Things were going so well that we kept going. We were still the furthest unit into Iraq, and moving northeast towards Kuwait, we started to pass more enemy positions with blown up tanks & unexploded bombs & mines that we had to avoid. Everyone did avoid them.

Furthur on that night we started to hear and see a lot of boom - booms to our south. That was the Republican Guards fighting our 3rd Armored Division. Our guns wiped them out that night. That’s also when our artillary started firing from behind us right over our heads. I was a bit nervous about a round falling short—but it didn’t happen. At about 11:30 PM we stopped to let our artillary prep the battlefield in front of us. Our troops were sending mortar on a road to our north, artillary was going off to my west, there was a major battle to our south. I saw a vehicle blow up and fly about 100 feet into the air—and to our east were the Republican Guards that we were going after—the Medina division. Every direction I turned there were explosions. Our vehicles were lined up in columns, mine being the last vehicle of our column. I was standing outside, when I saw something fire into a hill not 200 feet from me. I dove behind my humvee along with 2 other guys—we were sure we were getting shot at. We had our weapons out, ready to shoot at anything that moved. I thought the worst, but it turned out one of our own bradleys had fired that shot at a bunker near us. Scared by our own troops.

We moved a little furthur after the artillary barrage, then stopped for another one. I can’t describe to you the power that you feel when artillary goes off anywhere nearby. The earth shakes, your body vibrates, the sound is deafening. I watched as these rockets were being fired directly behind me—coming right at me and over my head, hitting about 10 miles to our front. They were beautiful to watch, but it must be hell on earth to be anywhere near where they land.

Most of our guys were sleeping at this stop, but I stayed awake and kept my eyes open to our rear. I wasn’t going to take any chances. I saw about 10 people coming over a hill with their hands over their heads—figured they were Iraqis surrendering. I rounded up a few guys with M-16 rifles & drove over to them. It turned out they were 11 soldiers from the Tawakalna Division of the Republican Guard—supposedly the most elite forces, surrendering to me. My guys seized their weapons & searched them. They were thin, disheveled, cold & dirty. I asked if any of them spoke english and I got a resounding “no” from most of them. I laughed at that and most of them responded with a nervous chuckle. I’m sure they were worried that we might just shoot them. We put all their weapons in my humvee and pointed them west—towards the rest of the Division following us. They were a little hesitant to walk away—I think they thought we would shoot them. Eventually they walked. I was left with 7 AK-47’s, Soviet made assault rifles. I got a picture of me holding them all, then Mascellino and I buried them. Now I can boast about how I singlehandely captured 11 enemy soldiers—could you imagine if that happened to Wags? Think how inflated that story would become.

We stopped again about 3 AM. Everyone was tired but ecstatic that things were going so well. It seemed too good to be true—and it was. We heard a loud “crack”,—much closer & different sounding than the ones we’d been hearing the last 2 days. Mascellino & I jumped out of our humvee and beelined for the nearest armored vehicle—an ambulance 2 up from me. As I ran up I twisted my ankle & limped towards the ambulance. I saw multiple explosions very close—right in front of me. I heard guys screaming and saw people running as I dove into the ambulance.

It stopped soon after I got in. We had been attacked by someone, somehow, somewhere—no one knew where it came from. I hobbled out and heard we had a lot of casualties at the TOC (tactical operations center) where about 100 soldiers live. I drove over there & saw guys laying out all over the place. I went to each one & checked them out—we had 21 casualties, but no one had a life threatening injury. It was a miracle. The artillary that hit us exploded over our head, where it shoots out a bunch of little bomblets that then explode when they hit the ground. They send shrapnel in all directions. We dressed all the wounds, sorted the patients & put guys on ambulances who couldn’t walk. By then it was 5:30 AM, we tried to get some sleep for an hour, but I don’t think anyone slept. The explosions that we’d been hearing the last 2 days and had adjusted to now made everyone very nervous. When the sun came up we re-checked all wounds & I decided who needed to be evacuated & who could stop with us. We ended up sending eight guys back to hospitals—wherever they are now.

We were incredibly lucky. With all that shrapnel flying around, no one had any vital organs or eyes pierced. Someone was definitely watching over us then. You know I’m not too religious, but I just can’t attribute our good fortune to luck alone. I think I may have seen the power of your prayers that night.

That scene totally changed the attitude of the squadron. Immediately, we all realized what war really meant, and everyone hated it. I have never been as scared as when that stuff exploded. Since then, everyone wore their frag vest (body armor) & most slept in armored vehicles. We all jump a bit more when we hear explosions.

We still don’t know where that came from—but it was most likely from our own guys. Friendly fire that wasn’t.

We moved up a few more miles yesterday morning, then stopped and let the Division pass us by. They battled all day yesterday with tanks, apache helicopters, artillary and jets going after the retreating Iraqis. By last night I was delirious—I hadn’t slept in 38 hours. I crashed in the ambulance & slept a solid 10 hours, woken up intermittently by the explosions around us, hoping that they were outgoing and not incoming.

This morning I woke up and heard the second best news in my life—Pres. Bush announcing a cease fire. I was working on patients later this morning when I then heard the best news in my life—that Iraq had accepted the cease fire terms. Hopefully that’s it, but I won’t believe it for sure until I’m out of here.

The sun’s now setting & to the east I can see the red glow of an oil field burning under dark clouds, with a full moon rising above the clouds. It’s beautiful.

Please save this letter—it’s as much a journal as a letter. I don’t think I’ll write anybody else in this detail, so feel free to share this with anybody—ie. our parents.

I think about you & my sons all the time—you’ve kept me going through this ordeal, I can’t wait to get home.

I love you,

Putt

S. Sgt. Dan Welch, a tank commander with the 1st Infantry Division, Seventh Corps, was also elated by Iraq’s surrender. But in a letter written to his mother and extended family back in Maine a week later, Welch began to express more ambivalence about the brief, almost surreal war he had just experienced. Welch was also unsettled by the Allies’ decision not to assist the Iraqi rebels struggling to topple Hussein. (Marianne is his wife and Chris is his three-year-old son. Although Welch states that he is writing from the “King Faud Military City,” he later realized he was, in fact, at the King Khalid Military City.)

8 March 91

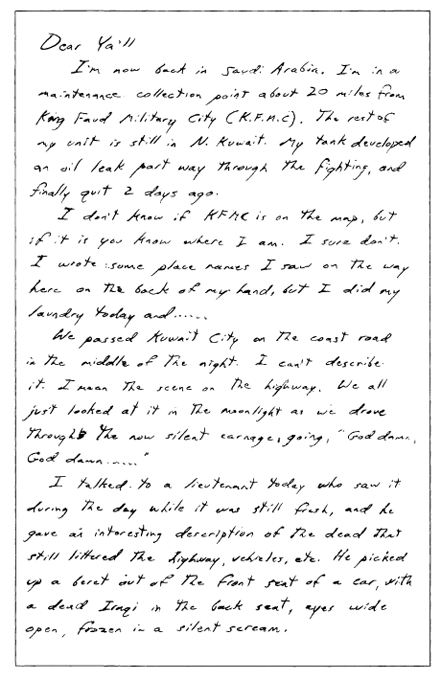

Dear Y’all

I’m now back in Saudi Arabia. I’m in a maintenance collection point about 20 miles from King Faud Military City (K.F.M.C). The rest of my unit is still in N. Kuwait. My tank developed an oil leak part way through the fighting, and finally quit 2 days ago.

I don’t know if KFMC is on the map, but if it is you know where I am. I sure don’t. I wrote some place names I saw on the way here on the back of my hand, but I did my laundry today and……

We passed Kuwait City on the coast road in the middle of the night. I can’t describe it. I mean the scene on the highway. We all just looked at it in the moonlight as we drove through the now silent carnage, going “God damn, God damn……”

I talked to a lieutenant today who saw it during the day while it was still fresh, and he gave an interesting description of the dead that still littered the highway, vehicles, etc. He picked up a beret out of the front seat of a car, with a dead Iraqi in the back seat, eyes wide open, frozen in a silent scream.

I still think of the guy I shot the day before we attacked. If I hadn’t done it, he could have been in an EPW camp right now, waiting to go home, just like me. He probably would have surrendered along with most of the others, just one day later.

We should be able to get to the phones in the next day or two. You’ll already know if I did when you get this.

They’re talking we’ll be here like probably three weeks or so, then move into the KFMC itself for 3 weeks or so, and then move from there toward the aircraft. We heard the first guys got home today. 100 from 24th Mech at Ft. Stewart.

I guess I haven’t said anything much about what I’d done during the ground war. I started writing to Marianne about it, but it didn’t come out right. We didn’t do much shooting, though we (my tank) expended more ammo than any of the others in my platoon. We never shot another tank or vehicle, except one suspect tank, that, after the dust from the artillery settled, ended up an already dead heavy truck. We shot up some trenches and bunkers, mostly empty. But you never really know. We ran over some AP mines and unexploded DPICM and cluster bombs here and there, received some incoming artillery off to our flank once, etc. Mine missed an anti-tank mine by about 2 feet on the right side once coming around a dune, and at our speed would have probably gone off under my gunner and I.

It never seemed like a war. More like a field problem. Even when stuff was burning all around you and firing going off all over the place, artillery firing from behind you and landing to your front. It was very real, but more a curiosity than anything else. I just can’t describe it.

Like one time 21 was right next to me, and we were on the move. He was on my right, and ran over an AP mine or submunition with his left track. It exploded and sent shit flying past me. I was up out of my hatch, and the first thing that came to mind was can I get to my camera before the smoke clears? I didn’t even think to duck. And the L.T. (21) just throws his hands up and smiles, like “Oh well”.

The first time I ran over one I thought that 23, to my left had fired his main gun. I didn’t realize ’till one of the others ran over one what had happened. Sometimes the stuff blows a hole through the track, etc. Sometimes it doesn’t scratch it.

When we were breaching the main Iraqi defense line in the neutral zone, an idiot popped up with an AK from a trench and started firing. Mine was the first to return fire, and he didn’t pop back up. Although the muzzle fask was pointing at us, you just don’t think of it as someone shooting at you. Just a target and you engage it, like on a range.

Right after I released the mineroller and was linking back up with the platoon, some incoming artillery rounds landed maybe 300–400 yards from us to the left and my only consideration was that it wasn’t a very good shot. And the second volley never came, so I just figured that our counter-battery must have had better aim.

Can you understand what I’m saying? I think I would have had to have gotten hit for it to seem different. I guess I’ve played it so much for the last ten years that it just didn’t seem much different than the training. I’ve had field problems that were tougher. This only lasted for four days. It wasn’t even long enough to seem like a war. The waiting and worrying before we did it were worse than doing it.

The only time I was ever really afraid was a couple of weeks before we did it. Then I got over that. After that, the only time I thought much about it was when I would picture that split second as the impact would rip my cupola from the turret and half my body would collapse onto my gunner’s back, and the resulting tears back home. But not even that from the time the prep bombardment ended and we rolled forward through the cease fire.

The thing that was hardest for me was knowing how Marianne and you, Ma, were probably taking this back home. The image I’ve had of you two sitting in front of the T.V. afraid that I’m already dead, can and has choked me up and brought tears to my eyes. Even now as I write this I’m hoping that Marianne isn’t still waiting for the “We’re sorry” Team to come knock at the door. I wish I could get to a phone to relieve the pain.

You don’t know what it’s like to hold an M-16 up to a man’s back and make him clear out of a trench, and pick up a few pieces of rock hard bread, blue and green with mold, and break pieces off and eat them.

Or realizing you came a few feet from crushing live men that you thought were dead, and only saw at the last moment because they were too afraid to stand up.

It’s only been the last couple of days that I’ve come to realize the horror that has taken place here. It’s not a personal feeling of horror, but more an overall picture of horror. And I think it’s taken so long because with only the small number of exceptions on our part, it was almost entirely theirs.

I can only imagine what it was like for those who were part of the carnage of which we witnessed the silent aftermath on that highway. It is just so very strange.

I’m just now realizing the significance of all these things I’ve been through and seen, that were at the time merely curiosities. It’s just different now. I don’t know if I’m really explaining it or leaving you wondering what the hell I’m trying to get across.

I wish that that night that we were mopping up the remains of that republican guards division that there had been another one behind it, so that there would be less of them left. We have now left the rebels in Iraq with a much harder problem to solve in their struggle. And when we pulled up to Basra, we had to halt for about an hour while a battalion of Rep. Gds. T-72’s pulled out of the positions that we sat in for 3 days before we withdrew. They left one behind that they couldn’t get started, and I smashed out all the optics and visions blocks with a tanker’s bar with delight, knowing how much work and money they’d spent fixing it. We should have torched it after we stripped it, but by that time it was a no-no.

The news said that rebels had come to our lines asking us to join them, and also said they were running short on ammo. Of course we couldn’t join them, but I and others would have led them to the vast stock piles in our vicinity if they had come to us.

I think we’ve made a mistake and not finished this the way it should have been ended. There is now a weakness in my heart for the people of Iraq. I’m still trying to explain what has gone on here. The next time you go to the drive-thru at McDonalds, remember that you haven’t been living off rice, onions, and radiator water in your hole in the ground for the last month and a half, hoping you won’t be exterminated by a pilot you don’t hate, because someone told you if you didn’t they would kill you and your family.

The next time you see someone throwing garbage at the White House, know that a helicopter is not going to spray them with nerve gas.

Don’t hate the guy that has been busy burning Kuwait hotels and dragging people off, because it’s been happening in his hometown for quite a while now, and by now he probably doesn’t even realize what he’s doing.

It may appear to most of us over here and to you back home that we’ve done our jobs, but we’ve screwed up and didn’t finish it. He’s still alive, and unless somehow the rebels finish what we’ve started, we may be back.

I guess I’m finally starting to feel I’ve fought in a war.

This is what I expected it to be like in the first place before I came over here. It just took a while for it to sink in that it really was. I think the easy victory just clouded the undertones until I reflected on it for a while here tonight.

But I still think we did the right thing, although we didn’t go far enough. I still like what I do, this hasn’t changed that. And I’m not psycologically scarred or maimed for life. If anything, this has just reinforced all I’ve believed in before I came over here. And I’ll be home soon.

Love,

Dan

P.S. I hope you’re saving all my letters. Someday I’d like to go through them with Chris.

“The specter of Vietnam has been buried forever in the desert sands of the Arabian peninsula,” President Bush declared after the war. With a staggering 90 percent approval rating in 1991, Bush’s reelection seemed guaranteed. But after the U.S. economy slipped into a recession, Bush was defeated by Governor Bill Clinton of Arkansas in 1992. Upon hearing the news, a jubilant Saddam Hussein stepped onto the terrace of his presidential office and celebrated by firing a pistol into the air. Hussein would outlast President Clinton as well.