5 Bodies

A rocky escarpment rises in a densely wooded area a short distance to the north of the monumental temple dedicated to Juno Sospita at Lanuvium (Latium, approx. 33 km southwest of Rome; see Table 3.1) (Figure 3.2). The face of the cliff is traversed by a series of fissures and cavities through which natural spring water has worked its way for thousands of years. During the Roman Republic, this area – known today as Pantanacci – was used for the quarrying of peperino stone and for the passage of an aqueduct and, later, an imperial period necropolis (Attenni and Ghini 2014, p. 153). In 2012, thanks to the swift intervention of the Guardia di Finanza who successfully thwarted a clandestine excavation, at least one of the larger cavities in the crag was revealed to have also served as a location for cult activities involving the dedication of offerings to an unknown deity. Over a thousand ceramic vessels and terracotta models in the form of figurines and body parts had been routinely deposited between the fourth and second centuries BCE in a wide, low-roofed cave where a shallow natural basin collects the spring water that still filters through its walls (Attenni and Ghini 2014, p. 156; Attenni 2017; Attenni and Ghini 2017). Among the assemblage of offerings, 33% of the items studied to date comprises impasto and black-glazed vessels, including small cups and miniature skyphoi (Attenni and Ghini 2017, p. 63); the remainder primarily comprises a large quantity of terracotta anatomical votives (Attenni 2017, p. 29 reports a total of at least 1,500 terracotta votives, but only 1,020 of all types of object from the cave have been studied at the time of writing). Among the terracotta items, nearly all known types of anatomical model were represented, except for eyes, with a high proportion of uteri (8%), statuettes (7%), and male heads (5%), as well as an unusual set of oral cavities (4%) (Attenni and Ghini 2014, p. 158, fig. 9; see also Attenni and Ghini 2017, p. 67).

The cave and its assemblage of votive offerings is significant for the number of individual objects recovered and the range of forms represented. It is also remarkable for the almost unique opportunity it provides to explore a cult site in which the dedicated items remain in situ. Unlike so many other votive assemblages of the period, which are recovered from the pits into which dedicated objects were periodically cleared to make space for the display of new offerings (known variously as stipes, favissae, or bothroi), the cave at Pantanacci preserves the original (or near original) location of the objects that were dedicated there. Hence, anatomical models of body parts are found carefully inserted into small, artificial niches cut into the walls of the cave or placed in slots cut into the ground close to its walls and ‘protected’ by surrounding retaining stones, with access to both provided by large slabs of flat peperino stone that the excavators suggest were laid down to create a level floor surface to aid the movement of dedicants (Attenni and Ghini 2014, pp. 156–7). The centre of the cave, where a layer of silt indicates that the spring water was probably once collected, was left free from offerings, but ceramic vessels and sometimes anatomical votives were also positioned on flat stones in such a way as to allow the naturally occurring water to flow from the walls directly over them, leading to a build-up of calcium on their surfaces (Attenni and Ghini 2014, pp. 156–7). What is more, while coarse impasto and much finer black-glazed miniature ceramic vessels were filled and sealed with fine clay, some of the anatomical models were also stacked together, one inserted into the concave cavity of another. Evidence for burning detected on the walls and some of the stones and tiles within the cave, along with the charred remains of peas, nuts, shellfish, poultry, and sheep, also suggests that foodstuffs were offered to the divine alongside these more durable objects (Attenni 2013, p. 6; Attenni and Ghini 2014, pp. 156–7).

The cave at Pantanacci, with its preservation of the material components of deeply personal activities performed in accordance with what appear to be potentially highly localised traditions (the covering of objects with clay), has relevance for any study of lived ancient religion, but particularly one such as this which seeks specifically to explore the impact of the relationship between human and more-than-human material things in the production of religion. Not only do many of the objects implicated in the cult practices at Pantanacci make visual reference to the human (and animal) body in the form of figurines and anatomical votives, but the circumstances of their recovery makes it possible to investigate how those living and artificial bodies interacted during the course of dedicatory rites in ways that are more difficult for sites where offerings are only found in secondary deposits. Some of these are hinted at by an image produced by the excavators shortly after the discovery of the cave (Figure 5.1). This reconstructs a possible scene at Pantanacci: cult participants are shown holding various objects (terracotta votives, woven baskets of food, ceramic vessels) and gesturing with their bodies while others are depicted moving towards and around the cave as they crouch or stretch to place their offering in its chosen place; meanwhile, flowers float on the spring water of the pool and lamps, braziers, small fires, and torches flicker and cast shadows in the semi-darkness. It may be fictionalised, but the image prompts questions about these experiences and compels us to recognise that they were a product not only of human intentions but also the agency that resulted from engagements between humans and the more-than-human world, including the unique locational qualities of the natural rock cavity and the material objects that were introduced to it.

In the previous chapter, I suggested that via sensory perception the individual human body operated in conjunction with the material affordances of the things that it manipulated and was manipulated by in the course of particular ritualised activities. These material engagements, in turn, produced specific forms of understanding and, consequently, highly personal or proximal forms of religious knowledge that acted simultaneously to locate the performer in relation to a wider context of shared distal knowledge. To investigate in more detail the powerful combination of material human and more-than-human things, this chapter takes this argument one step further, extending it to an earlier period (the middle Republic), another context (personal votive cult rather than public sacrifice), and to different types of object (models that replicated the very body that came into sensory contact with them). In order to do this, it is necessary to problematise the presumed boundary between living and artificial bodies and to consider the ways in which it might be intentionally blurred, as well as why that might be desirable in the context of certain ritualised activities.

Figure 5.1 Reconstruction of votive activities at the cave of Pantanacci (near Lanuvium, Latium)

Source: Luca Attenni, Donors at the Shrine. Used with permission.

Anatomical votives: an overview

The cave at Pantanacci is one of several hundred sites from mid-Republican Italy to be associated with so-called anatomical votives. Well over a decade ago now, Fay Glinister (2006, p. 13, n. 11) estimated that anatomical votives could be associated with around 290 individual sites, although the addition of the assemblage from Pantanacci, as well as other recently identified locations and newly published assemblages, means that this figure continues to be revised upwards (e.g. Fidenae: Barbina et al. 2009; di Gennaro and Ceccarelli 2012; Monte Li Santi-Le Rote at Narce: De Lucia Brolli and Tabolli 2015). Anatomical votives are usually considered to be almost ubiquitous within assemblages of objects dedicated at sites used for the celebration of votive cult in mid-Republican Italy. They are commonly dated, rather generically on stylistic grounds and often without supporting stratigraphic or contextual evidence, to a period between the late fourth and second or early first century BCE. They nevertheless have clear antecedents in copper-alloy (i.e. bronze) figurative models of heroes and deities (Scarpellini 2013) as well as terracotta human heads which appear in slightly earlier periods (Söderlind 2002). The reason for their decline and disappearance in Italy from the late second century BCE onwards remains the subject of debate, with an explanation yet to be offered which is entirely satisfactory or wholly accepted (Schultz 2006; Glinister 2006; Flemming 2016; de Cazanove 2017; Graham 2017b). Their comparatively restricted period of popularity in Italy nevertheless points towards a discrete and context-specific material response to a human concern about how to enact and sustain mortal-divine relations, rather than the sudden emergence and decline of that concern itself. If, indeed, anatomical votives were connected, as they commonly are in modern scholarship, with universal human worries about health, well-being, bodily integrity, fertility, and security, it seems unlikely that these issues were of concern for only a few centuries. We are simply fortunate that, for a restricted period of time, those concerns were addressed using a form of material culture that was durable enough to survive in the archaeological record.

So what is, or was, an anatomical votive? At its most fundamental level a votive, or ex-voto, is a gift of thanks made to a divine being subsequent to the making of a vow, perhaps as an acknowledgement of its fulfilment on the part of the mortal participant, or as thanks for divine intervention (Osborne 2004; Dasen 2012; Hickson Hahn 2012; Graham forthcoming b). The reciprocal and formal relationship entailed by the vow is summed up by the Latin phrase do ut des (‘I give so that you may give’), with the material offering itself usually deemed to relate to the circumstances of the vow. Anatomical votives are a specific type of votive dedication which directly references the human body usually, but not always, by means of its fragmentation into disparate parts (e.g. Dasen 2012; see Hughes 2008 for a compelling critique of the necessity for the body to be represented as fragmented) (Figure 2.2). On the one hand, then, they appear to be easily definable as

Yet while they may be easy to recognise, anatomical votives nevertheless remain difficult to interpret. Scholars from a range of backgrounds, including artefact specialists, medical and religious historians, scholars of the ancient body, and material culture theorists, continue to pose new questions about their form, function, and meaning within the sphere of ancient life, health, identity, and ritual practice (for a critical overview of recent approaches, see Graham and Draycott 2017, pp. 10–17). Doing so is, however, further complicated by the fact that although anatomical ex-votos are known from across the ancient Mediterranean region and beyond, appearing at both Middle Minoan peak sanctuaries (2000–1650 BCE) and in imperial Roman provincial contexts, not to mention featuring in much more recent Catholic contexts, the impression of continuity that this presents can be misleading. Closer inspection reveals a much more complicated picture of local and chronological variation in both the form and function of anatomical votives (Hughes 2017a).

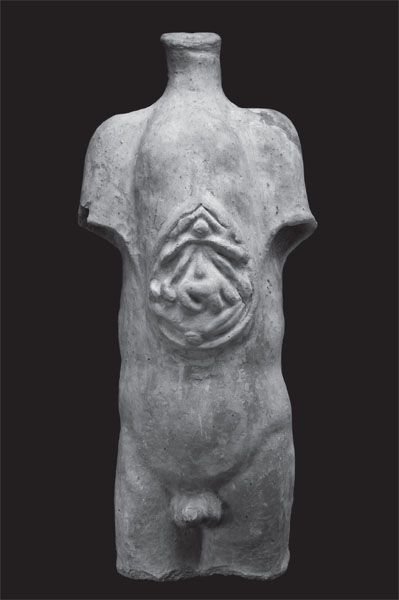

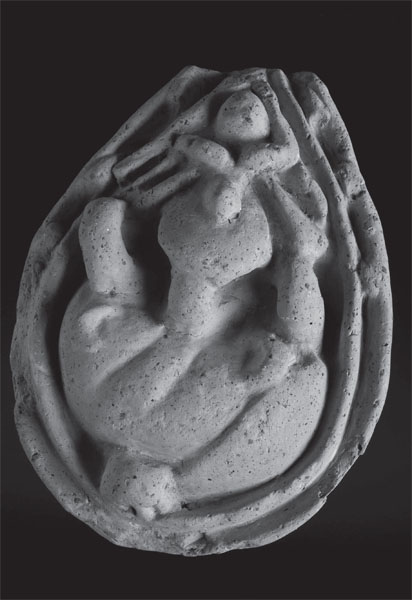

Those of mid-Republican Italy, with which this chapter is concerned, were most often modelled using clay pressed into pre-made reusable moulds which produced three-dimensional models which were then fired. They vary from miniature to life-size (Figure 5.2), with occasional examples of body parts depicted with over-life-size dimensions. These models recreate both internal and external body parts and organs, such as uteri (Figures 5.3 and 5.13), hearts, bladders (Figure 5.4), and sometimes collections of internal organs shown as a single mass or viewed through an incision in a model of a torso (Recke 2013; Haumesser 2017; Flemming 2017; Fabbri 2019) (Figures 5.5 and 5.9). Terracotta dominates the mid-Republican Italic assemblages, although there are also many copper-alloy (bronze) examples, which more commonly take a miniaturised form and tend to come from more northerly or interior Italic sites where small metal figurines dominate (e.g. the bronze ear and inscribed bronze breast from San Casciano dei Bagni, Siena: Iozzo 2013; see also Scarpellini 2013; Fabbri 2019, pp. 153–7). The anatomical votives of ancient Italy therefore differ from the stone relief carvings which depict only external body parts found at sites in Classical period Greece, such as at Athens, and even from the terracotta models of external body parts (one possible stomach aside) known from the Asclepieion at Corinth (Roebuck 1951). They also differ from the miniature metal sheet ex-votos dedicated at southern Italian Catholic shrines in more recent centuries, as well as other forms elsewhere (Weinryb 2016a). The importance of acknowledging this diversity within anatomical votive practice has been demonstrated most vividly by Jessica Hughes (2017a) in her comparative study of body part votives from contexts in Classical Greece, Republican Italy, Roman Gaul, and Lydia and Phrygia in the second and third centuries CE. Focusing on the significance of the decision by people acting in each of these cultural and historical contexts to fragment the body, but also the differences between the nature and use of anatomical votives in different regions and periods, Hughes asserts the need to consider ‘how different populations received and reshaped the votive tradition’ which, ultimately, can ‘help us to reconstruct how the votives were adapted and modified to fit different craft traditions, as well as changing beliefs about the human body and mortal-divine relations’ (Hughes 2017a, p. 20).

Figure 5.2 Terracotta anatomical votives in the form of a (slightly over-) life-size hand and a miniature forearm, provenance and date unknown. Wellcome Library inv. R2707/1936 and unknown. Wellcome Library, London.

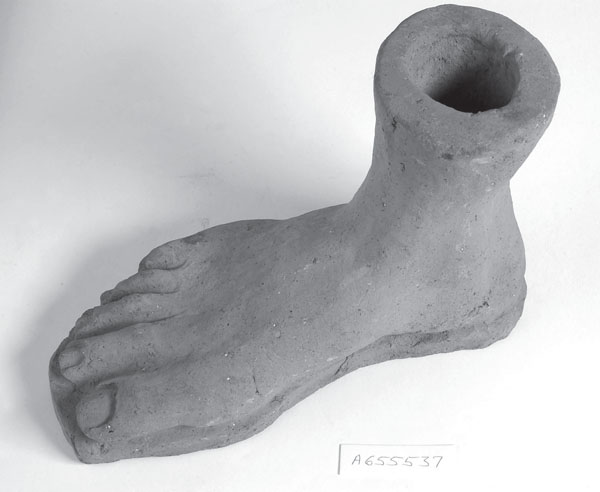

These variations notwithstanding, anatomical votives have customarily been associated with a tradition of petitioning or thanking the divine for intervention in the health and well-being of the dedicant, with the form of the object usually supposed to represent the area of the body that was subject to illness or disease, or which required some other form of positive intervention by the divine (e.g. Comella 1982–83; Potter and Wells 1985; Girardon 1993; Turfa 2004, 2006a, 2006b; Edlund-Berry 2006a; Glinister 2006; Recke 2013; Flemming 2016). As a result, many are also linked to the sphere of fertility, especially those of varying type which have collectively been interpreted as representations of uteri (although not without hesitation by some scholars: King 2017), as well as breasts, phalli, and vulvae, and some very rare examples of pregnant torsos (Baggieri et al. 1999; Turfa 2004; Weinryb 2016b). Nevertheless, alternative evaluations of anatomical models diverge from the purely medical, as well as from largely misguided attempts at retrospective diagnosis: eyes, for example, might reference mysteric vision and cultic enlightenment (Petridou 2017) or provide acknowledgement that a deity was ‘watching over’ someone (Figure 5.6); feet such as the examples shown in Figures 2.2 and 5.8 might be connected to pilgrimage, travel, or the idea of metaphorical movement from one state of being to another (Graham 2016, forthcoming a); uteri might be representative of the fertile future of a newly married couple, or an attempt to express in material form a complex combination of ‘folk tradition’ and medical concepts of the ‘wandering womb’ (Flemming 2017).

Figure 5.4 Terracotta anatomical votive model of an internal organ, probably a bladder, provenance and date unknown. Wellcome Library inv. A636057. Wellcome Library, London.

Olivier de Cazanove (2013) has expressed discomfort with what he describes as more ‘abstract’ interpretations such as these but, typological studies aside, Anglophone scholarship on anatomical votives has increasingly acknowledged that at least part of the potential agency that the anatomical votives of the ancient world might help to produce lies in the abundance of interpretations that might be ascribed to, or affected by, the material nature of these models of the fragmented body (Hughes 2008, 2017a; Petsalis-Diomidis 2005, 2010, 2016; Draycott and Graham 2017; Graham 2017a, 2020a). To this end, recent work has framed anatomical votives in relation to questions about bodily fragmentation and disability (Hughes 2008; Adams 2017; Graham 2016), as well as exploring the relevance of ideas concerning alternative, largely non-Western forms of personhood (Graham 2017b) and human-animal hybridity (Hughes 2010, 2017a). Other studies have begun to consider anatomical votives as material objects in their own right, that is, as things which possess their own discrete more-than-human characteristics with the capacity to affect the living body via the senses (Graham 2017a, 2020a; Hughes 2017b; 2018a, 2018b).

This chapter brings these new approaches together to explore how, in particular contexts, living bodies combined with the material duplication of those same bodies (or parts of them) to produce lived religion. Focusing primarily on issues of sensory perception, especially the tactility of votive things, and using the assemblage from Pantanacci as a point of departure, it will therefore consider the role of votives as more-than-human things within certain types of ritualised assemblages. To this end, I employ the concepts of relational agency, ritualised assemblages, and distal and proximal religious knowledge explored in previous chapters to consider the consequences of votive things in the production of religious agency, including how they might generate lived religion that could be experienced as both deeply personal and communal. In the process I will place a much greater emphasis than many existing studies have on the materialness or thingly qualities of different types of votive body parts as a factor that was central to these processes of religious knowledge production.

Figure 5.6 Terracotta anatomical votive in the form of an eye, provenance and date unknown. Wellcome Library inv. A114897. Wellcome Library, London.

Hand in hand with anatomical votives

One of the striking things about the anatomical votives of the central regions of mid-Republican Italy is the extent to which the vast majority can be connected in some way with the sensory functioning of the living body, or with the potential of the bodily senses to provide metaphorical ways of understanding the self. I have already noted that eyes might be connected with enlightenment, but more traditional interpretations have always associated them with requests for the healing of visual impairments or eye conditions. Given their frequency as offerings at some sites, this connection has even led to the suggestion (far from universally accepted) that certain ancient sanctuaries offered specialised ophthalmological services or treatments (Oberhelman 2014; contra Turfa 2006b, who argues that there was no space for medical professionals at Italic sanctuaries). Similarly, ears are often taken to imply that many ancient people experienced hearing impairments, although an alternative might be that the petitioner sought to thank the divine for hearing their prayer (or to express a wish that they would do so), or used it to acknowledge that they had themselves heard or would listen to what a god intended for them. The much later second century CE orator Aelius Aristides, for example, was repeatedly instructed by Asclepius to undertake particular tasks or journeys (Petsalis-Diomidis 2010). In terms of smell and taste, noses and tongues remain rare finds in assemblages of anatomical votives, although the Wellcome Collection in London includes at least two unprovenanced examples of possible tongues (inv. A636143 and inv. A636144) as well as a pair of ‘tongue and tonsils’ (inv. A634928). The unusual series of oral cavities found at Pantanacci which depict the lower jaw, tongue, throat, and oesophagus may also have been connected with gustatory conditions which affected the sense of taste and smell. As noted earlier, feet might reference injuries, mobility impairments, or a much more general sense of movement, such as the sense of moving from one state of being to another (unwell to healthy, adolescent to adult, unmarried to married, and so forth) (Graham forthcoming a). Even models of open torsos might be connected with the lesser known sense of interoception, that is, the sense of the state of one’s internal body. This is commonly described in relation to being able to sense when one is, for instance, hungry, nervous, or nauseous, but might also relate to a general sense of illness or, in an ancient context, to an unexplained imbalance of the humours. Additionally, it might be noted that votives moulded in the form of swaddled infants appear in the same deposits as anatomical votives and show fabric wrappings tightly covering newborn bodies while leaving the sense organs free, including the ears and feet (Graham 2014) (Figure 8.1). It is not difficult, therefore, to detect a connection with the senses, and of the importance of sensory perception, among the known types of anatomical votive, including those where it might be least expected.

One sense that is only occasionally mentioned in connection with votives is that of touch (for an exception, see Hughes 2018a). This is despite the fact that the models themselves required the human body to touch or otherwise manipulate them order to fulfil their function as dedications, and that they signify parts of the body that might be intimately involved in the affordance of tactile or more broadly haptic experiences and understandings of the world (e.g. feet, but more especially hands). Until recently, scholarship had left unquestioned what it might be like to touch, manipulate, hold, or carry objects which not only represented but embodied, even became one’s own body in the course of a votive dedication. Yet, look closely at Figure 5.1 and the woman shown approaching the cave entrance can be seen clutching a model of a hand in her own left hand, suggesting that it is high time that we began asking questions not just about how votives related to the senses but how they were themselves sensed, or in other words questions about what it might have meant to hold your own hand.

As a starting point for this, we can turn to the words of Merleau-Ponty (1968, p. 133), according to whom bodies grasp and affect the world via things, but ‘only if my hand, while it is felt from within, is also accessible from without, itself tangible … if it takes its place among the things it touches, is in a sense one of them’. His observation emphasises, as I have done elsewhere in this book, that living hands (i.e. our fleshly bodies) are as much a part of the material world as other material things. Living bodies, he suggests, are responsible for making the material world and, in turn, are made by it. For him, the significance of objects lies in what he termed their ‘flesh’, in other words the fact that not only humans but all objects, plants, and animals – in other words everything that is categorised in this book as a more-than-human thing – have mutually affecting properties which are inherent to their existence as physical things. As already discussed, this way of thinking has informed new materialist archaeologies, especially the stress it places on how all things share ‘membership in a dwelt-in world’ in which they all have ‘the capacity for making a difference to the world and to other beings’ (Olsen 2010, p. 9 original emphasis). This capacity of things to affect other things was introduced in Chapter 2 before being explored in relation to the locational qualities of place (Chapter 3) and the sensory affordances of specific material objects incorporated into public ritual action (Chapter 4). In the previous chapter, it became apparent that the affordances of objects used by some participants in public sacrifice affected their bodies, via the senses, to create particularly personal lived experiences of religion and consequent religious knowledge. Merleau-Ponty’s description of his own hand in relation to ‘the things it touches’ and its own reciprocal tangibility therefore reinforces the role of this mutual affectivity in understanding the relationship between human bodies and things principally because it allows things that are conventionally characterised as objects to be reframed as things that are the equal of human bodies. Put another way, hands grasp and manipulate objects, but as things those objects also manipulate the grasping body itself, since their material properties (e.g. weight, temperature, texture, and form) affect and determine how it is manipulated in that moment (Graham 2020a, p. 222). As we saw with the incense boxes, things grasp us back.

With these ideas in mind, it becomes possible to build on what has been established so far about the production of religious agency and knowledge as it was afforded by the largely ‘practical’ items demanded by the needs of public sacrifice in Chapter 4, to explore more complex material things. That is to say that although potential material affordances underpinned my investigation of incense boxes (acerrae) and the spiked leather cap (galerus/apex) of the flamen Dialis, in those instances the participants in sacrificial ritual action were not faced with the prospect of interacting with things that might blur the conceptual boundaries between their body and another ‘body’ in quite the way that anatomical models might. Without doubt, when Merleau-Ponty wrote of the reciprocal tangibility of his hand, he was not thinking about it being grasped back by another more-than-human thing that also took the form of a hand, but of course in the context of the ritualised assemblages associated with ancient anatomical votive cult that might become a very real possibility, one that deserves closer scrutiny.

In an earlier study (Graham 2020a), I approached this issue from the perspective of object theory, arguing that it was the material thingliness of terracotta anatomical votives of hands which allowed them to exist simultaneously as (a) a representation of a hand, (b) a stand-in for the actual living hand of the dedicator, and (c) an individual, objective “hand” that was a material thing in its own right. To explain, imagine for a moment that you are holding a life-size terracotta model of a hand like that in Figure 5.7. You might note that to all intents and purposes it looks very much like a hand, and perhaps under certain circumstances you might even imagine using it to represent or stand in for your own hand. By moving it around, you can even hold it in a way that makes it feel dimly familiar to other hands that you have touched or clasped in the past. However, it will reveal itself to be something entirely other – a thing in its own right – when you try to engage with it in other ways: when you squeeze it, or expect the fingers to bend in order to clasp your own in the form of a handshake; when you smell, taste, or hear it (by knocking it against another object or surface); or when you wait for it to move autonomously. Thus we can begin to appreciate not just the potential visual affordances of the model, which would afford its use as a representation of a/your hand but also its full material thingliness, complete with a range of potential affordances that might affect the way in which your living hand experiences it, or in other words which allow it to affect you in return. In this way, votive offerings such as hands ‘possess the potential to be more than they appear because of (a) what they physically are, (b) what they are made to do, and (c) what they make people do or understand as a result’ (Graham 2020a, pp. 228–9).

Figure 5.7 A terracotta anatomical votive in the form of a hand, provenance and date unknown. Wellcome Library inv. A95397. Wellcome Library, London.

This sort of approach to the study of anatomical votives allows our understandings of them to move beyond the visual and the representational, and responds directly to Bjørnar Olsen’s (2010, p. 34) concern that ‘studies of material culture have become increasingly focused on the mental and representational: material culture as metaphor, symbol, icon, message, and text – in short, as always something other than itself’. He proposes instead that researchers ‘pay less attention to things’ “meaning” in the ordinary sense – that is, the way they may function as part of a signifying system’, and more attention to the question, ‘What is the significance of things “in themselves?” ’ (Olsen 2010, p. 172; see also Chapter 2). This is, admittedly, something that is hard to do in practice, but as I continue to emphasise in this book, extending this sort of analysis to different types of thing, and paying attention to the potential affordances of all things, particularly when ritual compels them to form relationships with other things, offers one way of addressing Olsen’s question. Here that entails considering the multiple ways in which votive cult might require the active participant not just to grasp a model that served its purpose by standing for the idea of a hand or replacing a living hand with a proxy, but also to be grasped back by that hand.

Blurring bodily boundaries

Responding to Olsen’s plea that we move beyond understandings of objects as signifiers has significant implications for transforming how we think about and interpret the potentialities of anatomical votives in ritualised assemblages. Needless to say, conventional interpretations have emphasised an almost exclusively signifying standpoint, whereby it can be claimed that since a model of a hand is shaped to look like a hand, it must represent or substitute for a real hand or, at the very least, the concept of a hand and everything it might stand for, from illness and injury to marriage and oaths (dextrarum iunctio) and even manumission (Graham 2020a, p. 221). Paying closer attention to the thingliness of the votive object itself transforms such claims into something far more interesting by opening up a host of other potentialities: although a model of a hand certainly presents visual affordances that allow it to resemble a living hand, as a more-than-human thing in its own right it also possesses other affective qualities with the potential to combine with the mutually affective affordances of the human body in ways that extend beyond the visual or representational. As we have seen, these might include affordances connected with rigidity, lack of autonomous movement, and so on. In contrast to its visual affordances, these offer to an assemblage a set of potentialities that are substantially different and independent from those made available by a living hand. We are reminded too, that these other qualities need not necessarily always be offset by the immediate representational capacities of the model, and that they are important for extending the range of potential relationships that we can reasonably suppose might be forged between the components of an assemblage. In fact, much like the props used in theatre performances (Carlson 2001; Sofer 2003; Mueller 2016), because anatomical models of hands still retain the capacity to ‘ghost’ other objects (real hands) and the ideas associated with them (what hands might be expected to represent) alongside these other qualities, human sensory attention might be expressly drawn to the dissonance produced by this multiplicity of divergent qualities and to the fundamental material ‘otherness’ that it implies, leading to an acknowledgement that this model is definitely not always a hand (Graham 2017a, 2020a, p. 228). When the complex thingliness of votive hands is fully recognised in this way, they can be better appreciated as things with the capacity to exist somewhere between a proxy for a real hand and a representational hand, simultaneously being both and neither. As a result they might be considered to acquire a set of quotation marks that signal their strange ontological status as something in between, that is as “hands” in their own right.

The religious agency that might be produced when living bodies interacted with more-than-human “hands”, “feet”, “eyes”, and so forth as part of a ritualised assemblage was therefore much more complex than conventional scholarly understandings of the ex-voto as a material stand-in or purely visual reference point for the fulfilment of a vow have tended to assume. From this new perspective, the representational capacities of anatomical votives to look like parts of the body continue to be important; after all, it was necessary that they look like a hand, a foot, or an eye for them to retain their correlation with the situationally specific petition or vow and the person who made it. At the same time, however, emphasising their material thingliness means that it becomes possible to acknowledge that it was also inescapably apparent that an anatomical votive did not feel, taste, smell, sound, or move quite like the living body. Whether this ambiguity was openly acknowledged or not, it may well have been these uncanny qualities as they were perceived by the human body and mind that enabled anatomical votives to affect a very particular manifestation of religious agency appropriate for the distally shaped context of votive cult. That is to say that the capacity of an anatomical votive to be an extension of the human body and a more-than-human thing at the same time was, in fact, entirely suited to a context in which distal religious knowledge determined that the votive petitioner might expect to experience or understand the world as slightly other than it normally was. After all, votive cult was often about seeking, controlling, and celebrating personal transformation, be that of the ill or injured body, of bodies moving through the life-course, or of changing fortunes, status, or identity.

When it came to specific concerns about health, fertility, and well-being, making a votive offering frequently involved communicating with the divine in such a way as to intentionally blur the edges of one’s body anyway, quite literally opening oneself up to transformation and inviting the positive beneficence of the divine to enter or otherwise combine with it (Graham 2017b; Petridou 2017, 2020). It has been suggested, for instance, that open torso models could speak directly to the process of surgery, in some instances even featuring the suture holes necessary for the body’s reassembly in a new form (Recke 2013, pp. 1078–9), a concept that might even be extended to include the prospect of ‘divine surgery’. This is in effect what is evidenced elsewhere by contemporary epigraphic sources, including the fourth century BCE ‘miracle tales’ (iamata) from Epidaurus in Greece, where Asclepius is reported to have intervened directly in the body via sometimes quite violent surgical acts (Edelstein and Edelstein 1945 [1998]; LiDonnici 1992; Dillon 1994).

What is more, in a less literal sense, the type of intervention that anatomical votive cult in Italy seems to have expressly sought is generally characterised as involving a process of exchange as part of the do ut des arrangement: when making a vow and dedicating an anatomical offering, mortals effectively surrendered their own body to the divine, even if via a proxy or in the manner of pars pro toto (a part for the whole), while in return they anticipated that a deity would permeate their living body with their otherwise intangible healing or protective essence. This acknowledgement of the inherent dividuality of human and divine bodies, or in other words their capacity to exchange either partible or permeable aspects of themselves and thereby create a relationship in which they became temporarily enchained, allows us to imagine how the context of votive cult was one that promoted the idea that humans and gods could effectively come to comprise aspects of one another (C. Fowler 2004, p. 9; Graham 2017b; see also Chapman 2000; Fowler 2016). The result of a human-divine communication featuring an anatomical votive as one component of its ritualised assemblage might therefore be the blurring of mortal and divine bodies and the forging of new composite or even communal bodies (Graham 2017b; the consequences of this sort of dividuality are explored further in Chapter 6). It is reasonable to suppose that the shifting thingly qualities of an anatomical model, of a thing that both was and was not the petitioner’s body, might be an especially effective component in producing the religious agency necessary for such a circumstance.

Additionally, Jessica Hughes (2017a, p. 103) draws attention to the role of anatomical votives in the production of fuzzy bodily boundaries when she argues that body-part votives helped to establish ‘a specially demarcated ritual space in which boundaries were transgressed, and in which it was possible for bodies and objects to move between one state and another’. Examining models of internal organs presenting human and/or animal viscera, as well as an unusual pair of polyvisceral plaques from Tessennano which actively create human-animal hybrids by depicting the trachea in the form of a snake with eyes, Hughes (2017a, p. 97) asserts that

She goes on to explain how ‘this ambiguity would in turn have given a powerful message about the equivalence or even interchangeability of the two types of body, which in other parts of ancient life were kept at much greater conceptual distance’ (Hughes 2017a, p. 99).

All in all, then, and following the argument developed in Chapters 3 and 4, both the places in which anatomical votive practices occurred and the agentic consequences of the thingly assemblages that those ritualised actions caused to emerge point towards lived experiences of religion that embraced and encouraged a multiplicity of blurred boundaries. At the heart of this were material things which simultaneously represented or became proxies for human bodies while always retaining their own ontological status as things in their own right.

Fluid bodies at Pantanacci

To what extent might a more nuanced and multi-layered understanding of anatomical ex-votos as more-than-human things alter the ways in which we think about how the other body parts represented in votive assemblages from mid-Republican Italy contributed to the production of lived religion? To explore this, let’s return to some of the objects recovered as part of the votive assemblage from Pantanacci.

Feet

Among the petitioners engaging in dedicatory rituals at Pantanacci in the scene pictured in Figure 5.1 is a mature man leaning on a stick. He accompanies the woman shown clutching a hand model as they both make their way towards the cave. The man uses his free hand to carry a life-size clay model of a foot not dissimilar to that shown in Figure 5.8. The scene may have been imagined by a modern illustrator, but both hands and feet, along with arms and legs, were recovered from the deposits in the cave, indicating that people did make journeys to it in order to make such offerings (Attenni and Ghini 2014, p. 158). With no evidence recovered for a workshop or kiln in the immediate vicinity of the cave (although until further investigation confirms this, it remains a possibility), all petitioners would have been required to carry their offerings from further afield as this man is shown doing. Examining the illustration in light of the earlier discussion, however, raises new questions about the experiences of the real-life equivalents of this fictional man as they became ritually assembled with an anatomical votive in the form of a foot/“foot”.

Feet are parts of the living body which, under normal circumstances, are experienced in multisensory ways: they can be seen, touched by the fingers and hands, and sometimes also smelled (especially if infected or diseased). Feet can themselves sense the world in tactile and haptic ways as their skin comes into contact with the ground, detecting its contours during movement or the textures and friction provided by different floor coverings and footwear. Equally, under normal circumstances, they cannot be held or carried in the way in which the man in Figure 5.1 is seen to clutch the model around the heel, the toes turned towards his back, resting it close to his hip. Living feet do not afford this experience, which is one that requires the body to be fragmented, dismembered, or otherwise not as it should be. Unlike the woman who grasps the model of a hand, the man in Figure 5.1 is therefore shown experiencing a foot, be it his or that of someone else, in an entirely unnatural way. To use the terminology introduced earlier, this was something that was afforded entirely by the object’s thingly status as a “foot” rather than its role as a proxy for his real foot. The “foot” itself most likely exhibited many of the same material affordances as that of the hands described previously, presenting the beholder’s senses with qualities that made it feel cold, hard, dry, heavy, solid, unyielding, rough around the edges but smooth on the flatter surfaces, that made it look like a very rigid foot with the inflexible toes joined together, and which caused it to smell of earthy terracotta. As before, affordances such as these perhaps affected a sense of strangeness or foreignness, an experience which was not at all like any associated with the foot which it was to substitute for when given as an offering (this is of course something that might also apply in circumstances involving other body parts too, as we shall see).

And yet, if the man was engaged in making an offering in conjunction with a request or thanks concerning an injured, diseased, or otherwise painful foot (which in the fictionalised image the viewer is led to assume, based on his use of a walking stick), then perhaps the ways in which these affordances affected him worked within the ritualised assemblage of which they were both part to produce religious agency that his existing distal knowledge permitted him to understand as entirely appropriate. The dislocated, stiff deadweight of the “foot” may have recalled his experience of a living foot that was comparably unwieldy, heavy, unresponsive, and thus ‘abnormal’, a foot over which he had perhaps lost control, not only in a mobility sense but perhaps also in terms of his ability to stop it causing pain or discomfort, a foot that both was and was no longer entirely his own. Alternatively, if experiencing numbness caused by nerve damage (neuropathy) or poor circulation (perhaps caused by diabetes or peripheral vascular disease), the congruence between the apparently unfeeling thingliness of the “foot” and the equally unfeeling living foot may have been equally as striking. Given that the model was to be dedicated and left behind in the cave, this conceptual and physical blurring of foot with “foot”, and therefore between things experienced as they are and as they should or might be, potentially offered a means of substantiating the process of separation and surrender that dedication itself involved. In other words, the “foot” that both was and was not his made it possible to actually experience the giving up of a physical part of himself to the divine. At that moment, the man’s foot would no longer really be entirely his own anyway, since it would subsequently have been bequeathed to the divine, in both its terracotta “foot” form as a sacred dedication and in the sense that the divine had taken (or was anticipated to take) ownership of his living foot in order to heal it. In this way, the combined material thingliness of both his body and the ex-voto afforded religious agency, that is, the act of ritual dedication caused them to assemble in a way that made a particular sort of difference to the world that the petitioner understood in relation to his distal (religious) experiences and expectations.

Of course, at a proximal level, another person bringing a foot/“foot” to the cave would have experienced something comparable yet dissimilar, either as a result of different personal circumstances, the specific qualities of the model they engaged with, or because they associated that “foot” with their movement to the cave as a pilgrim, or because they sought to give thanks for a successful journey or for some other form of social mobility or metaphorical movement (Graham 2016, forthcoming a). Regardless of the meaning that the petitioner’s mind ascribed to the votive object – its signifying potential – the material affordances of the anatomical model itself, and its capacity to affect experiences in which it was both foot and “foot”, had the potential to allow something out of the ordinary to occur on each of these occasions. Under normal circumstances, it was impossible for any person to walk away from the cave at Pantanacci having left their foot behind, but the ambiguities of the votive “foot” afforded exactly that outcome. Approaching anatomical votives as fully fledged thingly components of ritualised assemblages thereby makes it possible to better understand how these bundles of things enabled a type of agency that was special or out of the ordinary.

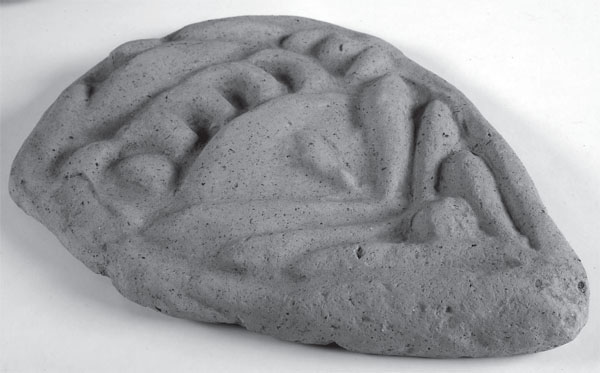

Internal organs

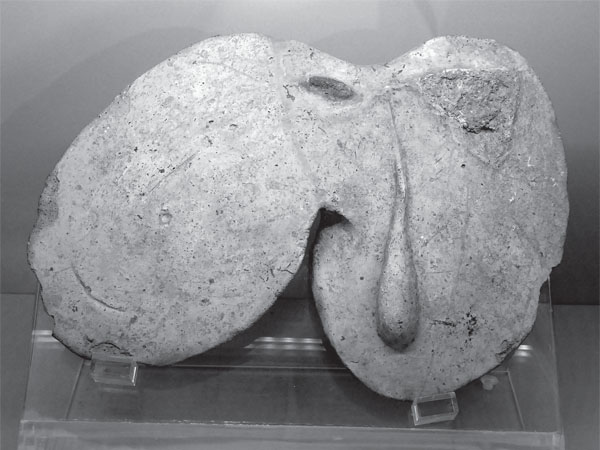

An ancient person might not expect to hold their own feet in the course of their lifetime, but they might at least expect to see and touch them. In contrast, most would almost certainly hope never to do the same with any of the organs in the interior of their body. And yet, in the course of anatomical votive cult, this became a very real possibility. Anatomical votives in the form of internal body parts appear to be unique to Italic assemblages and took a number of different forms, including isolated organs (uteri are the most common, but stomachs, bladders, lungs, and hearts are also known: Turfa 1994; Flemming 2017; Fabbri 2019) as well as piles of excised viscera (Figure 5.9) and teardrop-shaped polyvisceral plaques (Figures 5.10 and 5.12), both of which represent the organs collectively but without reference to the somatic exterior. As we have already seen, torso figurines might also be shown as if they were cut open, revealing a section of the body’s interior in situ, such as that in Figure 5.5 (Decouflé 1964; Turfa 1994; Recke 2013, p. 1081; Haumesser 2017; Hughes 2017a, pp. 81–3). Several of these types were recovered at Pantanacci: individual models of uteri (at least 65 examples) and bladders, as well as miniature polyvisceral plaques and miniature open torsos similar to the one shown in Figure 5.11 (11 out of the 37 male full- or half-torso figurines from Pantanacci show polyvisceral details: Attenni and Ghini 2014, p. 159). To these should perhaps also be added the set of oral cavities which reveal the inside of the head and upper digestive system in an unnatural manner by slicing away the maxilla, palate, and skull.

Many ancient participants in votive rituals will probably have been familiar with the internal organs of animals as a result of encounters with them during sacrifices, butchery work, and in the course of agricultural life and its inevitable veterinary crises (Söderlind 2004; de Cazanove 2013). Others who had experienced the violence of warfare or who acted as physicians or healers may have seen, smelled, or touched the internal organs of their fellows or patients, although the frequency of such experiences is difficult to estimate (Turfa 1994). Accordingly, any existing knowledge of the nature of the interior of the living mammalian body, however limited, will have underscored its smooth, elastic, flexible, slippery, and vulnerable nature, something which contrasted starkly with the affordances proffered by interaction with an anatomical model of those same organs. Open torsos, polyvisceral plaques, and individual models essentially transformed the slick and pliable, powerfully smelling somatic interior into something that was hard, inflexible, rough, dry, impervious, and strong.

Figure 5.11 A terracotta anatomical votive in the form of a miniature figure with an open torso, provenance and date unknown. Wellcome Library inv. A23134. Science Museum, London.

Holding your own internal organs in terracotta form, with the knowledge that although they might look similar to those that you have seen elsewhere they are otherwise completely different, is likely to have had a similarly dissonant impact on petitioners as interacting with “hands” or “feet”. However, once again the specific materialness of the thing in their hands – its shape, texture, sound, and smell – and how that related to the version experienced by the living body, had the capacity to nuance that experience and the agency and knowledge that it helped to produce in important if subtle ways. Once again the model’s affordances emphasised the out-of-the-ordinary nature of the activities they were performing: in this instance it really was impossible to remove one or more internal organs and pass them to the divine before leaving the cave not only alive but healthier than before! Yet this is the agency that the model’s thingly qualities effectively facilitated under ritualised circumstances. Indeed, the affectivity of this assembled combination of human and more-than-human things not only afforded a difference to the world that was otherwise impossible, but it also afforded a bodily transformation that might be significant in terms of how this agency was rationalised as proximal religious knowledge. Put another way, the material qualities of terracotta models of “viscera” permitted the conversion of an innately ungraspable aspect of a person’s body into something solid, firm, and most significantly, much less vulnerable (Figure 5.12). It made a person’s somatic interior into a physical thing that could be grasped, and into which they could invest their hopes and expectations of the divine, but it did so in a way that continued to underscore its strangeness, never allowing them to lose sight of the knowledge that they were engaging in activities that were in many ways unreal and only possible in that ritualised moment. The boundaries of the petitioner’s living body, between inside and out, were therefore distorted at the same time as it also became a body that they now shared with the divine. In ordinary life, somatic boundaries such as these were very well defined, but in the ritualised context of votive activities this knowledge was reworked and turned upside down (or inside out): it was not only acceptable but necessary for the world to be temporarily other than it should be, and for slippery vulnerable intestines to be solid and impervious. Once again the votive object as a thing straddled the boundaries of bodies and of experiences, its thingly qualities blurring them and highlighting the authenticity of these experiences as much as their sheer impossibility, combining with the living body and mind to produce lived religion that was grounded in the qualities of the physical world.

In instances where votives such as these were connected with therapeutic requests for internal maladies, the inversion of reality that they afforded may also have contributed towards situationally specific understandings of the agency of divine healing that this produced, encouraging the petitioner to conceptualise their ailment in a particular way and, in the process, to make it materially tangible. As anthropologists Andrew Strathern and Pamela J. Stewart (2008, p. 67, emphasis added; see also Strathern and Stewart 1999) have pointed out,

It seems unlikely that lived experiences of being in the world led many ancient votive petitioners to expect an instant and total reversal of their symptoms, the removal of a debilitating condition, disease, or tumour, or the disappearance of an infected wound. This was agency that even ritualised assemblages could not be relied upon to afford. However, if the ritualised activities involved in the making of vows and giving of offerings are conceptualised as a ‘means of dealing with the experience of illness’, then the material thingliness of the votive offering itself can usefully be understood as playing a role in the production or perpetuation of a different sort of agency on which that knowledge was predicated. As Meredith McGuire (1990, p. 285) has observed, ‘since our important social relationships, our very sense of who we are, are intimately connected with our bodies and their routine functioning, being ill is disruptive and disordering’. The solidity of an open torso, internal organ, or visceral plaque reasserted in the real world the sense of positive order, of confidence, and of stability and safety that occurred when the divine had charge of that part of a person’s body. Even in the case of votive uteri, the form of which has posed many problems for scholars seeking to reconcile their strange shapes with modern anatomical knowledge (Turfa 1994; Baggieri et al. 1999; Flemming 2017; King 2017), the creation of something tangible that could afford exactly this sort of difference making was potentially more important than anatomical accuracy (Figure 5.13). The same might also be true for those instances in which a vow concerned a more abstract issue, perhaps an acknowledgement that the person was opening themselves fully to the powerful essence of the divine and establishing a relationship that was as firm, solid, and durable as the thingly offering itself.

Miniature bodies and body parts

As with other votive assemblages from across mid-Republican Italy, many figurines from the cave at Pantanacci rework the whole body in miniature, including those with and without an open torso, and depict particular body parts in under-life-size dimensions, such as the unusual oral cavities. As noted in Chapter 4, the act of miniaturisation, or of interacting with something that (in this instance) presents a body or a part of the body with dimensions that are less than those of the ordinary world, can be especially empowering (Bailey 2005; on miniature votives: Kiernan 2009; Hughes 2018b). Just as the fingers of the camillus holding an acerra explored the scene of sacrifice in which he was a participant, so too might clutching a smaller version of one’s own body (or that of a loved one) afford agency over that body and the disordered or concerning situation in which it found itself. The small size of the more-than-human material thing, coupled with the affectivity of its firmness and resilience to external force, made it controllable, perhaps rendering concerns about that body more manageable. Certainly it must have affected a lived experience which emphasised to the bearer how this agency was also effectively that of the all-knowing, all seeing, all-encompassing deity who was being petitioned, paralleling how they might experience the living body which sought their assistance and offering the dedicant a sort of god’s-eye view (or god’s-hand experience?) of how a deity might be capable of enclosing that body in their own – holding a human body and its destiny in their very hands.

Figure 5.13 Four terracotta anatomical votives in the form of uteri of different types, provenance and date unknown. Wellcome Library invs. A636083, A636082, A636075 and A155134. Science Museum, London.

Animal figurines and body parts

Votive activities also involved the manipulation of bodies belonging to others, including those of infants, wives, and husbands, but also very different types of body. Many anatomical votive assemblages from across the central Italic regions also feature miniature figurines of animals, including some life-size and miniaturised models of animal body parts (Söderlind 2004; Edlund-Berry 2004, pp. 369–71; de Cazanove 2013; Hughes 2017a, p. 77). Together, these models represent the type of animals with which the humans of mid-Republican Italy interacted as part of their daily lives, in particular those connected with agricultural activities, such as bovines (primarily cows and oxen), horses, sheep, goats, and pigs, or with hunting (wild boar, dogs, deer, and birds). Rarer examples include lions, elephants, owls, swans, and even three seals (from the South Sanctuary of the Sanctuary of Thirteen Altars at Lavinium: Söderlind 2004, p. 291). The majority of animal anatomical votives (i.e. those which fragment the body rather than presenting it whole) take the form of heads, limbs, and hooves, and at Pantanacci this includes one life-size horse hoof (Attenni and Ghini 2014, p. 159).

A very unusual example of a life-size model of a sheep’s liver (Figure 5.14), found at the temple of Scasato at Falerii Veteres (c. 300 BCE), remains perhaps the only certain reproduction of an animal’s internal organ, even if it remains possible that some of the organs presumed to be human were partly based on those of animals (Comella 1986; Turfa 1994; de Cazanove 2013, p. 27; Hughes 2017a, pp. 87–8). This terracotta liver model is customarily associated with the more well-known ‘Piacenza Liver’, a bronze model of the first century BCE inscribed with information about the heavens or, perhaps more accurately, presenting cosmic order projected onto metabolic order, which has been interpreted as an aid to divination (de Grummond 2013, pp. 542, 547). The extent to which the two models both share a real connection to divination remains uncertain, since the terracotta liver from Falerii Veteres was recovered from a votive context, is life-size, uninscribed, and quite unlike the miniaturised bronze from Piacenza. It is possible that it was dedicated not because the model itself had played an active role in divination (or the teaching of future haruspices), but as a substitute for a real liver connected with the health and well-being of an individual animal or, perhaps, with the liver-handling activities of a haruspex.

Figure 5.14 Life-size terracotta model of a sheep’s liver, c. 300 BCE. From the Scasato temple, Falerii Veteres (Etruria).

Photo: Emma-Jayne Graham. © Su concessione del museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia.

Jean Macintosh Turfa (2004, p. 106) once observed that ‘a votary carrying his red-painted heart or multicoloured visceral plaque to the altar would have resembled the haruspex, about to perform his divination’. It should also be remembered, however, that a haruspex himself might choose to make an offering related to the ongoing success of his particularly skilled role, perhaps formally acknowledging the close relationship with the divine that enabled him to perform the appropriate divinatory acts or perhaps even marking the successful completion of his training and the dedication of his life to interpreting divine will. It was surely in the best interests of any haruspex to remain on the best possible terms with the gods! Nonetheless, a haruspex offering a terracotta model of a liver must have experienced its thingly qualities in a significantly different way from those of a real, recently excised sheep’s liver. All of the contrasts noted previously for human internal organs will have applied, but in this instance the heightened familiarity and expectations of the haruspex would have become even more disrupted and inverted: for a man used to actively and intentionally manipulating a soft organ that was slippery with fresh blood, the dry, resistant clay of the votive “liver” presented an obstacle, with some of its affordances actively resisting his attempts to manoeuvre it in a familiar way. As a result, the material thingliness of the terracotta votive “liver”, when combined with the capacity of the human body to be affected by its qualities, had the potential to produce agentic effects which reinforced the difficulties inherent in the act of reading animal entrails (extispicy), even the fact that the divine world might sometimes resist interpretation.

From individual to communal bodies

Even if the activities performed as part of a ritual act of dedication were largely prescribed by distal religious knowledge concerning its do ut des nature, and despite the fact that the mould-made origin of the objects discussed here caused some of them to be almost identical in physical form, when ritualised behaviour obliged them to combine with the material bodies, memories, sensory capacities, expectations, hopes, and physical movements of individual human dedicants, votive cult practices produced a spectrum of lived experiences of religious agency. In turn, these constructed subtly nuanced proximal forms of knowledge concerning an individual’s body and their place in a complex world comprising mortals, gods, and other things. Nevertheless, the knowledge produced by these experiences was also rationalised in relation to existing understandings of how this religious world worked and how to maintain it. Distal forms of knowledge were, after all, necessary for structuring the performance of these ritualised activities and for bringing people to a location which exhibited traces of similar activities enacted by other members of their community. Much as votive cult was performed and thereby lived on an individual level, it might also be closely entwined with the production of shared communal forms of religious knowledge too.

At Pantanacci, it appears that dedicants interacted with and rearranged previously dedicated offerings. Items were sometimes ‘stacked’ (e.g. a mask inserted into the concave section of a swaddled baby), and the excavators suggested that the niches and cavities into which they were inserted were selected in order to facilitate a sort of grouping together of similar types of object (Attenni and Ghini 2014, p. 156). There was certainly an inclination towards augmenting or otherwise altering the material qualities of offerings of all types in order to make them into something other than they were before they were dedicated. This includes filling or covering ceramic vessels with clay and actively encouraging spring water to continually wash over some of the miniature ceramic vessels. From the early published data about the site it is not clear when these interventions took place, but it is probable that it was part of the act of dedication itself – although, of course, the stacking of anatomical votives would only have been possible if there was already an item to add to or ‘enhance’, unless we are to imagine offerings of very different type being made at the same time by the same person. In effect, these equally religiously ritualised actions created new and unique things as well as new assemblages of things, assemblages that extended beyond the personal one-to-one of anatomical body part and its respective living counterpart to combine multiple more-than-human and human things into new configurations.

The augmentation of one type of body or body part with another provides an interesting contrast to attempts evident from elsewhere in the cave to segregate different types of model by grouping them together, suggesting that there were a number of potential actions available to the community who worshipped there, as well as different interpretations of what was appropriate for particular circumstances. Nevertheless, this range of contrasting actions also points towards the performance of a series of communal acts, or at least the decision to engage actively with the actions of other members of the dedicatory community and the things that they had left behind. This raises a new set of questions. Did people return regularly to make repeated offerings, choosing to physically join together or otherwise associate these separate dedications? Did people actively seek out their own previous offerings or those of family, friends, or perhaps even strangers? To what extent did petitioners know whose offering belonged to whom when they were largely identical in appearance? What happens to the distinct material affordances of a model of one body part when it assembles with those of another? These questions cannot be answered based on the evidence from Pantanacci, but they resonate with many of the observations already made in this chapter, re-emphasising the transformative agency of ritualised activities that brought together people and material things. At the very least, the significance of such agency to those who frequented the cave appears to have been closely connected to the reassembling of things and the very physical joining of one body with another in order to create a new, composite one. In many ways these composite bodies remained incomplete and fragmentary, but they were physically and conceptually united in perpetuity as new thingly “bodies”. These choices also stress how ritualised assemblages featuring votives might be endlessly changeable, their reconfiguration offering new opportunities for the production and experience of different forms of lived religion suitable to different situations or the needs of the wider dedicatory community.

Evidence for similar forms of behaviour is absent at sites where anatomical votives are not found in situ, and these acts of reassembly may have been entirely unique to the community who frequented that particular cave at Pantanacci. It is not impossible, however, to identify other instances of the intentional reassembling of things into specific combinations that may or may not have affected particular types of religious agency. The third century BCE ex-votos recovered in situ from a series of rooms in multiple buildings at the sanctuary at Gravisca (Etruria), for example, certainly demonstrate a similar type of intentional grouping (Comella 1978, pp. 9–10). Here, material things appear to have been assembled in relation to specific buildings or rooms: anatomical ex-votos appear only sporadically in building α, but much more frequently in buildings β and γ, where in the latter they were concentrated especially in space G (all uteri) and in the former between Cortile I and oikos M (Comella 1978, p. 89). The distribution of types between these spaces also differs, with Cortile I containing almost all of the anatomical votives from this building (including ears, hands, feet, breasts, and female genitalia) but just over half the number of uteri that were recovered from oikos M (74 compared with 145: Comella 1978, p. 89). This is conventionally explained as a response to the identity or concerns of the divinity with which each particular space was associated, and may have been a part of the primary dedication process. Cortile I, for instance, is considered to have been the destination for offerings associated with the matrimonial aspects of the cult of Aphrodite-Turan, and M possibly with the reproductive sphere of Hera-Uni (Comella 1978, p. 92), although the reasoning behind this interpretation is rather circular. Moreover, the distribution of offerings within these discrete spaces was also ordered in specific ways. Space G, a large covered area, revealed groups of offerings: uteri were deposited to the north and at the centre, with heads and different types of statuette located to the southwest (Comella 1978, p. 92). Bringing specific types of model together in this way may have afforded a particular type of agency, with the congregation of large numbers not only attesting to the success of previous dedications but also collectively contributing to the ongoing production of religious agency in that setting.

A similar sort of division is evident for the offerings dedicated to an unknown deity or deities at a small altar shrine at Fontanile di Legnisina, Vulci (Etruria). The Etruscan deities Uni and Demetra are named on inscribed offerings found at this site, but the excavator also speculates about an association with a range of other chthonic figures such as Aplu, Hercle, and Menerva (Ricciardi 1988–89, p. 152). Here, an altar and enclosure were set up adjacent to the base of a steep slope, into which a small natural grotto opened. When excavated, the whole area including the grotto and the area inside and to the north of the enclosure was found to be covered with votive offerings of all types and featuring a great many anatomical votives (like Gravisca, uteri were dominant, with 284 examples). In the passageway of the grotto behind the altar were found metal objects along with a concentration of models of female genitalia and uteri which adhered to only one of the three different uteri typologies reported from the site as a whole (Category I, modelled in the round on a base or pedestal: Ricciardi 1988–89, p. 171; Flemming 2017, pp. 117–8). Other models, including other types of uteri and swaddled infants (seven examples), were found in the northeastern area of the enclosure, to the north side of the altar (Ricciardi 1988–89, p. 153). In addition, terracotta statuettes were also found mostly within the confines of the enclosure, with bronze figurines between the altar and the boulders behind it, whereas the ceramic materials were primarily located outside and to the north of the enclosure – observations which led excavator Laura Ricciardi (1988–89, p. 153) to speculate that other groupings might also have once been in evidence. Examples like this prompt interesting questions about the nature of the religious agency that might have been produced by assemblages comprising multiple, almost identical versions of the same sort of thing, in this case “uteri”.

It is unfortunately not entirely clear how far these evidently curated assemblages of objects at Gravisca and Fontanile di Legnisina reflect an act of primary dedication or secondary reorganisation by those responsible for the maintenance of the sanctuary. Nor is it clear what sort of diachronic processes might have affected their arrangement. It also remains possible that visitors to any sanctuary interacted with previous offerings in ways that are no longer visible to us, causing them to be brought into new ritualised assemblages along with their own individual material offering and living body. Offerings might be temporarily moved around to make space for new additions, in the process causing them to become stacked or grouped, and each dedicant may have made very individual choices about where to place an offering in relation to the others that were already on display: should I put my uterus next to the other uteri because this is what others have done (perhaps inadvertently, or even intentionally, prompting future visitors to do the same), or should I place it apart from them in order to ensure that when faced with such a multitude, the deity notices mine? Of course, such behaviour depends upon the rules and regulations concerning access to the location of deposition, so perhaps for large formal sanctuaries like Gravisca this was left to priests and caretakers and was not as easy as it was for (possibly) less formally controlled sites such as Pantanacci and Fontanile di Legnisina. Nevertheless, even if this degree of primary dedicatory freedom was specific to Pantanacci, it still suggests that under certain circumstances we should consider that the assemblages of human and more-than-human things that produced religious agency in the context of votive dedicatory behaviour might extend beyond a single offering to encompass other discrete assemblages of similar or different types, and perhaps even the bodies of the wider dedicatory community. In this way, it becomes possible to perceive how the intensely proximal experience of an assemblage forged in the context of the ritual dedication of a single ex-voto for an individual was also embedded and entwined with other assemblages of things and with a wider distally experienced world of things.

Conclusions

This survey of just some examples of anatomical votive types suggests that the material thingliness of votive objects, and the potential that they offered to the production of discrete instances of religious agency, coupled with their capacity as more-than-human things to ghost human ones in both familiar and unfamiliar ways, could produce a bewildering mix of intimacy and distance, of similarity and difference, and an almost uncanny sense of something which both was and was not the dedicant’s body. As things, votive objects certainly point towards concepts of the body and relationships with the divine in this period that were fluid and constantly in flux, which may have been derived in part from or reinforced by the tangible and materially physical thing of the anatomical ex-voto itself. This chapter has also established why this fluidity makes a particular sort of religious sense in the context of ritualised activities which were, after all, largely about the potential for transformation and surrendering control of one’s body, future well-being, and identity to the divine. Accordingly, when it comes to votive offerings, lived religion involved experiencing religious agency that derived from the qualities of an assemblage comprising specific somatic needs, complex bodies, and personal encounters with material things with an ontological status that was difficult to pin down. And yet, despite involving fundamentally personal experiences which produced proximal forms of knowledge concerning mortal-divine relationships, votive cult also produced and reinforced communal forms of knowledge concerning the distal world of religion. Holding one’s own hand might also mean holding the hand of another member of that community or even being held in return by the gods themselves. Reaching this conclusion means, however, that it is now time to turn our attention to the divine and their role within ritualised assemblages such as those that have been explored in this and previous chapters: were the divine also material things and, if so, what were the consequences for ancient lived religion?