CHAPTER 2

Beauty Happens

In the hilly rain forests of the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, and Borneo lives one of the most aesthetically extreme animals on the planet—the Great Argus (Argusianus grayi), which Darwin described as affording “good evidence that the most refined beauty may serve as a sexual charm, and for no other purpose.”

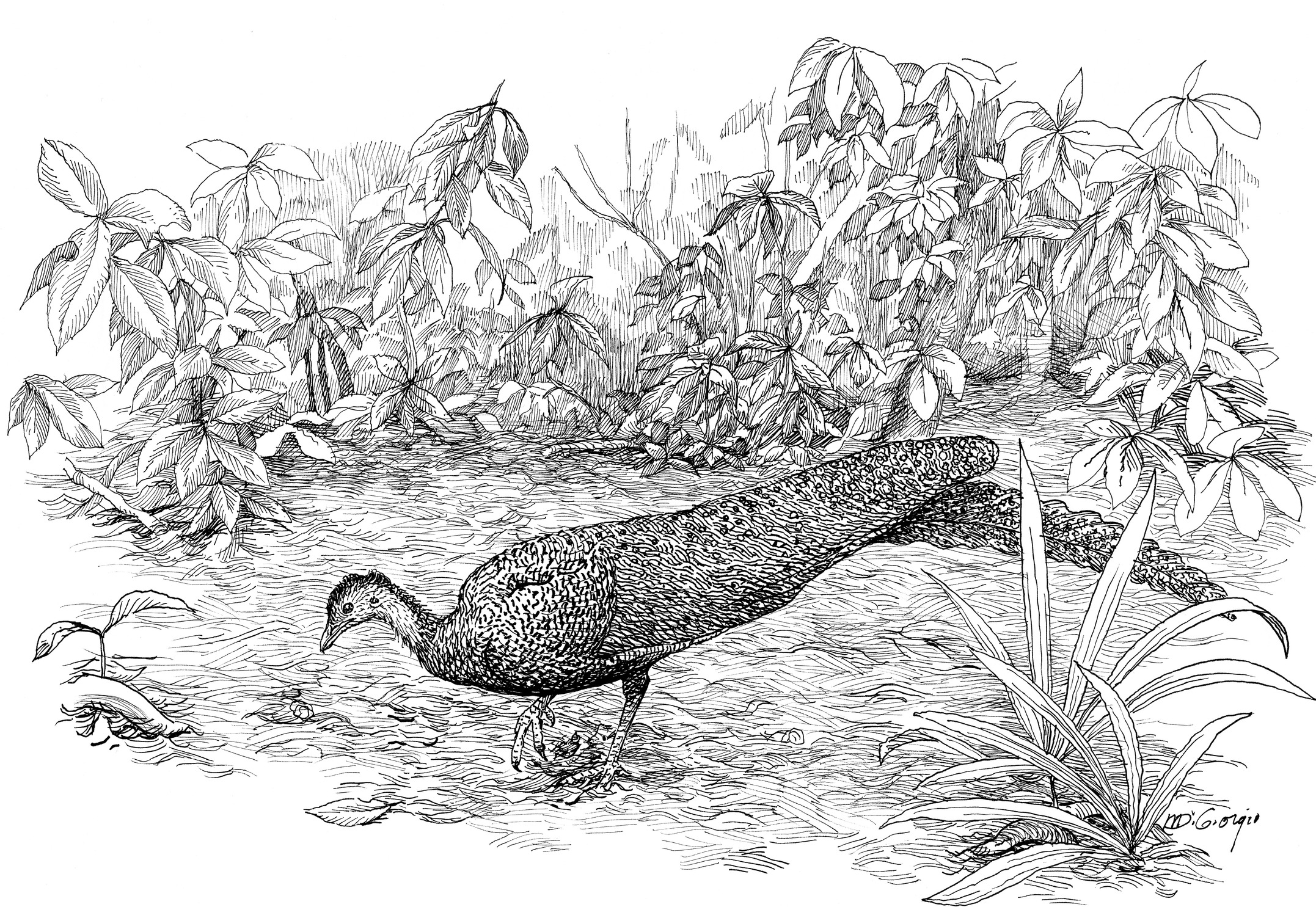

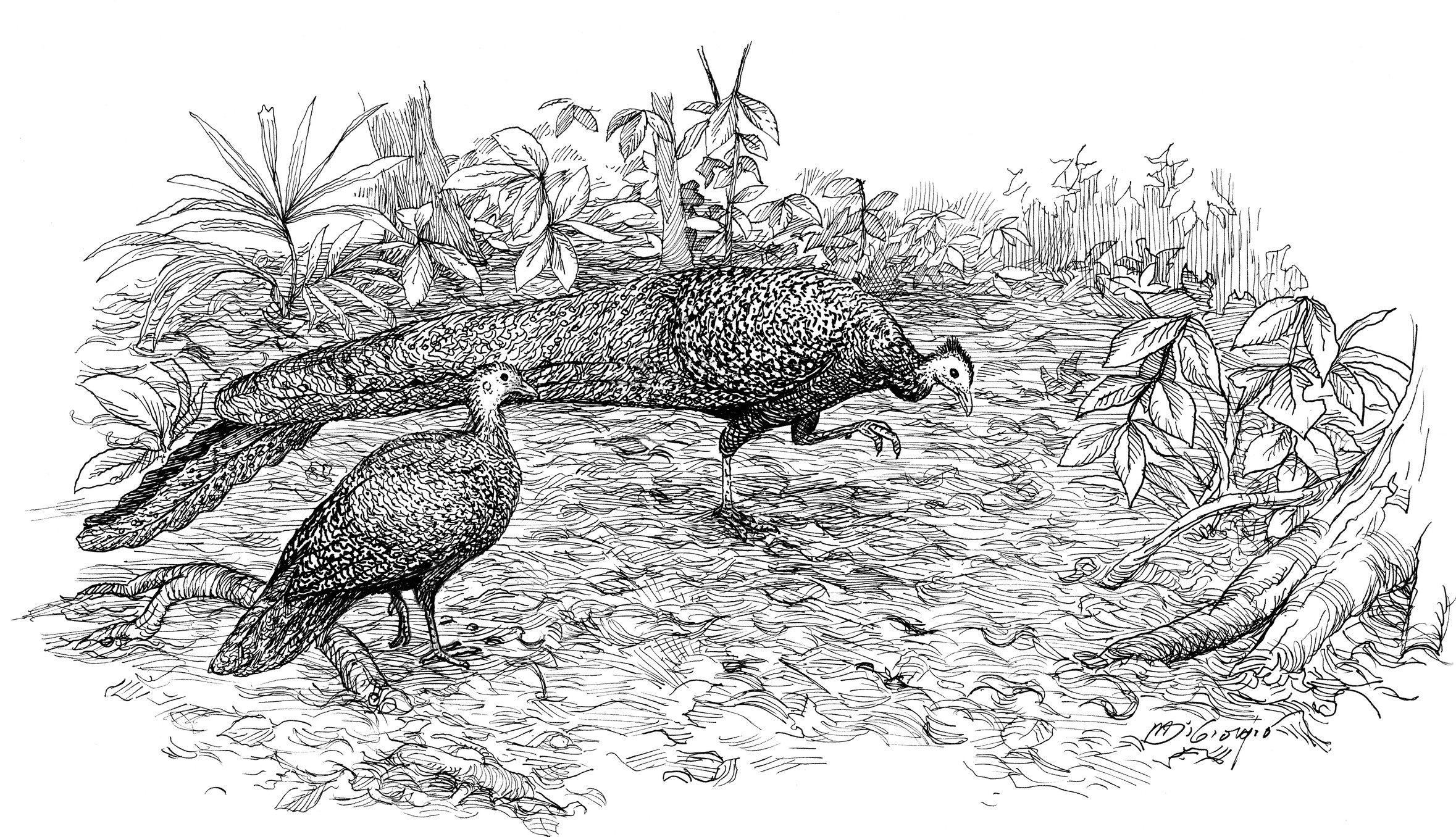

The female Great Argus is a large, robust pheasant with a complex, finely vermiculated, but dull camouflage pattern of chocolate-brown, reddish-brown, black, and tan swirls on her feathers. Her legs are bright red, and the feathers of her face are sparse, revealing bluish-gray skin beneath. At first view, the main thing that distinguishes the male Great Argus from the female is the great elongation of his tail and wing feathers. The feathers extend over a yard behind him. In total, the male Argus measures nearly six feet from the tip of his beak to the tip of his tail. But length aside, his plumage appears to be quite similar to that of the cryptic female, and he’s not particularly impressive looking. His real charms remain hidden, not to be revealed until the peak of his courtship of the female, which very few people on earth have ever witnessed outside the confines of a zoo.

Seeing a Great Argus in the wild is very difficult. They are extraordinarily wary and disappear into the forest at the first sign of your approach. The early twentieth-century ornithologist and pheasant fanatic William Beebe was among the first scientists to see the display of Great Argus in the wild. Beebe was a curator at the New York Zoological Society who would later become world famous for exploring the depths of the oceans in a bathysphere—a primitive, deep-diving submarine. Beebe saw his first Great Argus—a male—descending a muddy bank in tropical Borneo to drink from a puddle of rainwater that had collected in a wild boar wallow. He describes this first sighting ecstatically in his 1922 Monograph of the Pheasants, expressing his feeling of triumph in the language of both a proud bird-watcher and the American, colonial-era adventurer that he was: “Brief as the glimpse had been, I felt a great superiority to my fellow white men the world over, who had not seen an Argus Pheasant in its native home.”

As is typical of most avian aesthetic extremists, Great Argus are polygynous, which means that single males mate multiply with different females. However, the opportunity for multiple mating creates competition among males to attract mates. Some attractive males are highly successful, and others are not at all. The result is strong sexual selection for whatever display traits females prefer. After the female chooses a mate, the male’s participation in the reproduction is complete, and he plays no further role in the life of his mate or their offspring. The female is entirely responsible for building a nest of leaves on the ground, incubating her clutch of two eggs, protecting her chicks, and feeding them and herself, which she does by foraging for fruits and insects on the forest floor. Both females and males are reluctant fliers. When threatened, they usually escape by running away on foot. However, at night they fly up to a low perch to roost—except when the female is incubating her eggs, when she remains on the nest.

The male Great Argus lives an entirely separate, bachelor life. To create a stage large and pristine enough to accommodate his extraordinary courtship display, he clears an area four to six yards wide right down to the bare dirt of the forest floor. Assiduously picking up all the leaves, roots, and sticks in the space he’s chosen, often on a ridge or a hilltop within the forest, he carries them to the periphery of his court. Like a modern yardman (but without the ear protection), he also employs his huge wing feathers as a leaf blower by beating them rhythmically, sending all the remaining debris flying from his court until it is completely clear. He prunes any leafy vegetation or vines that grow into the court from above by snipping the branches with his beak. Once his court is ready for the business of mating, all he needs is a female visitor.

A male Great Argus maintaining his display courtyard.

To attract an audience, the male Argus calls from his court in the early morning and evening and also on moonlit nights. The Great Argus call is a loud, haunting two-note yelp, kwao-waao, which is the source of the names for the species in several Southeast Asian languages—for example, kuau in Malay and kuaow in Sumatran. The call is loud and piercing enough to be heard from great distances. Because the bird is so elusive, that’s usually all that a human visitor is likely to experience of the Great Argus in the wild.

A few years ago, I spent five days at a research station in the Danum Valley Conservation Area in northern Borneo within the range of the Great Argus. Late one afternoon, we wandered along a heavily wooded trail near the river, and I heard the loud kwao-waao of the male Great Argus, exactly as Beebe described. The call was so loud that I thought the bird must be just around the next bend in the trail, and I froze with excitement. However, I soon realized that he was calling from a considerable distance away on the other side of the river. Even if the male had kept calling, it would have taken us more time to reach him than there was sunlight left in the day. And even if we had been lucky enough to track him down at his court, he would almost certainly have fallen silent as we approached, only to melt away into the surrounding forest undetected. With nothing but the tantalizing echo of his call to confirm his existence, I could only imagine what it must have been like for Beebe to see this amazing bird.

When we returned to the research station that evening, having birded the leech-infested forests since well before dawn, we met the French artist boyfriend of a researcher at the camp. He was there to “paint the forest,” he told us. He then casually asked us to identify an unusual bird he had come across while taking a stroll in the late morning near camp. With complete nonchalance, he proceeded to describe a large fowl nearly two yards long that had walked across the dirt access road only three hundred yards from the main compound. After tromping through the forests for days without so much as a glimpse of the bird he had managed to see without even trying—or appreciating—I could barely conceal my envy at his great, unearned fortune. As I scratched my leech bites, I experienced the opposite of Beebe’s feeling of “great superiority” and could only mutter private curses to the Gods of Birding.

If catching even a glimpse of the Great Argus in the wild is a great challenge, to see what the male Argus actually does with his enormous wing and tail feathers during his courting of the female requires elaborate preparations and can turn into quite a protracted ordeal. William Beebe tried watching Great Argus from a pup tent set up by a court and from a blind suspended in a tree above a court, but both efforts were unsuccessful. Finally, he had his assistants dig a large foxhole in the ground behind a buttress root of the tree that was next to a male’s court. Seated in this foxhole and hidden by branches, he waited daily for most of a week until at last he observed the male enact a full-on courtship performance for a visiting female. Little did he know it, but Beebe had it easy! Fifty years later, the ornithologist G. W. H. Davison spent 191 days over a three-year period observing male Argus Pheasants in Malaysia. During his seven hundred hours of observations, Davison saw only one female visit. That is the equivalent of working forty-hour weeks for more than half a year. Needless to say, few people have ever had enough patience to do this, and most observations of Argus behavior come from birds in captivity.

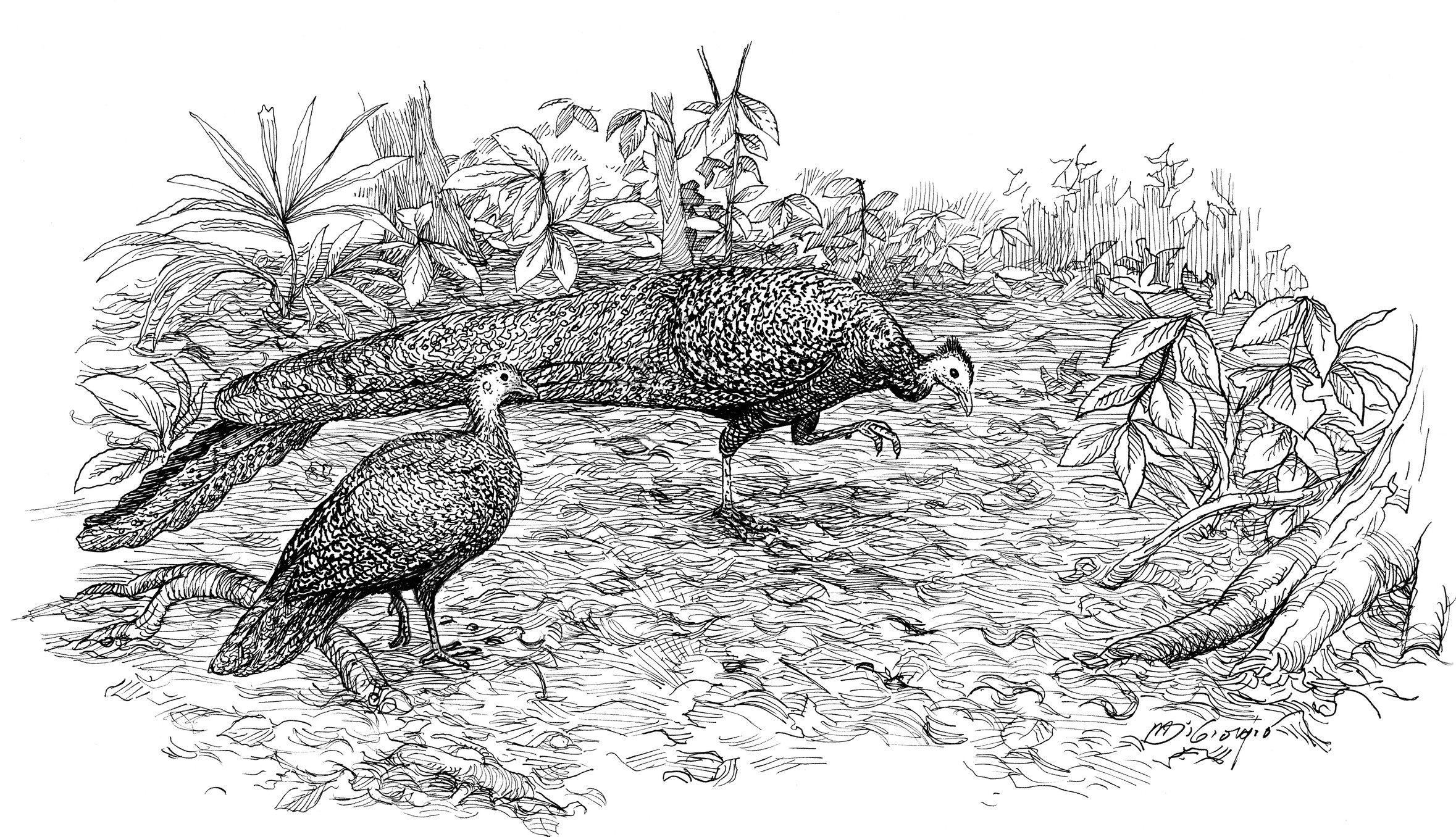

The strutting display of the male Great Argus.

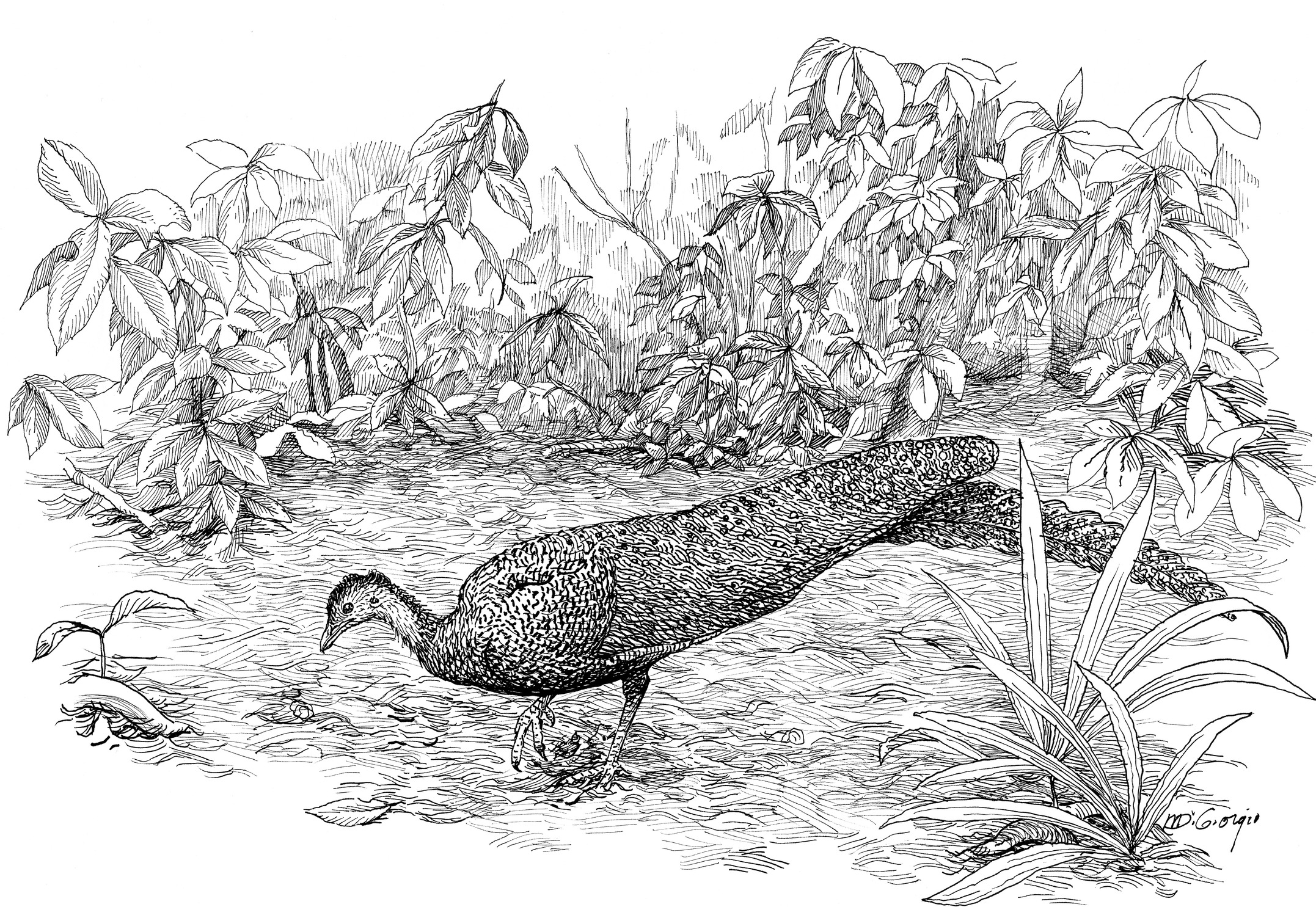

Here’s what happens when the female Argus arrives at a male’s court. The male first performs several preliminary displays, which include a ritualized pecking at the ground and elaborate, stylized strutting on his bright red legs. Eventually, he rushes around her in wide circles with his wings hunched up at an angle that exposes their upper surfaces. Then, without warning, when he is just a foot or two away from the female, the male transforms himself instantly into an entirely different shape, revealing unimaginably intricate color patterns on his four-foot-long wing feathers. In what biologists have come to refer to, with inexplicable reserve, as the “frontal movement,” the male bows down to the female, unfurling the elaborate feathers of his open wings into a huge hemispherical disk that extends forward, over his head, and partly surrounds the female from one side. In 1926, the pioneering Dutch animal behaviorist Johan Bierens de Haan compared this cone to the shape of an inverted umbrella blown out by a gust of wind.

In this extraordinary posture, the male tucks his head under one of his wings and peeks out at the female from behind the gap in his feathers formed at the “wrist” of his wing to gauge her reaction to his display. The deep blue of the facial skin that surrounds the male’s tiny black eye will be just visible to the female through the gap in his flexing wings. To support this extraordinary posture, the male perches athletically with one set of talons in front of the other like a sprinter in starting blocks. While bowing before the female, he raises his rear, cocks his long tail feathers, and pumps them rhythmically up and down so that the female can get sporadic glimpses of them over the top of the inverted cone of his wing feathers, or in the gap that sometimes opens up between the left and the right wings. The tips of the cone of wing feathers wave over the female’s head like a mini portable amphitheater. After repeated, throbbing shakes of the inverted feathery cone, lasting a total of two to fifteen seconds, the male transforms back into a “normal” bird shape and resumes his ritualized pecking of the ground for a few seconds before repeating the display.

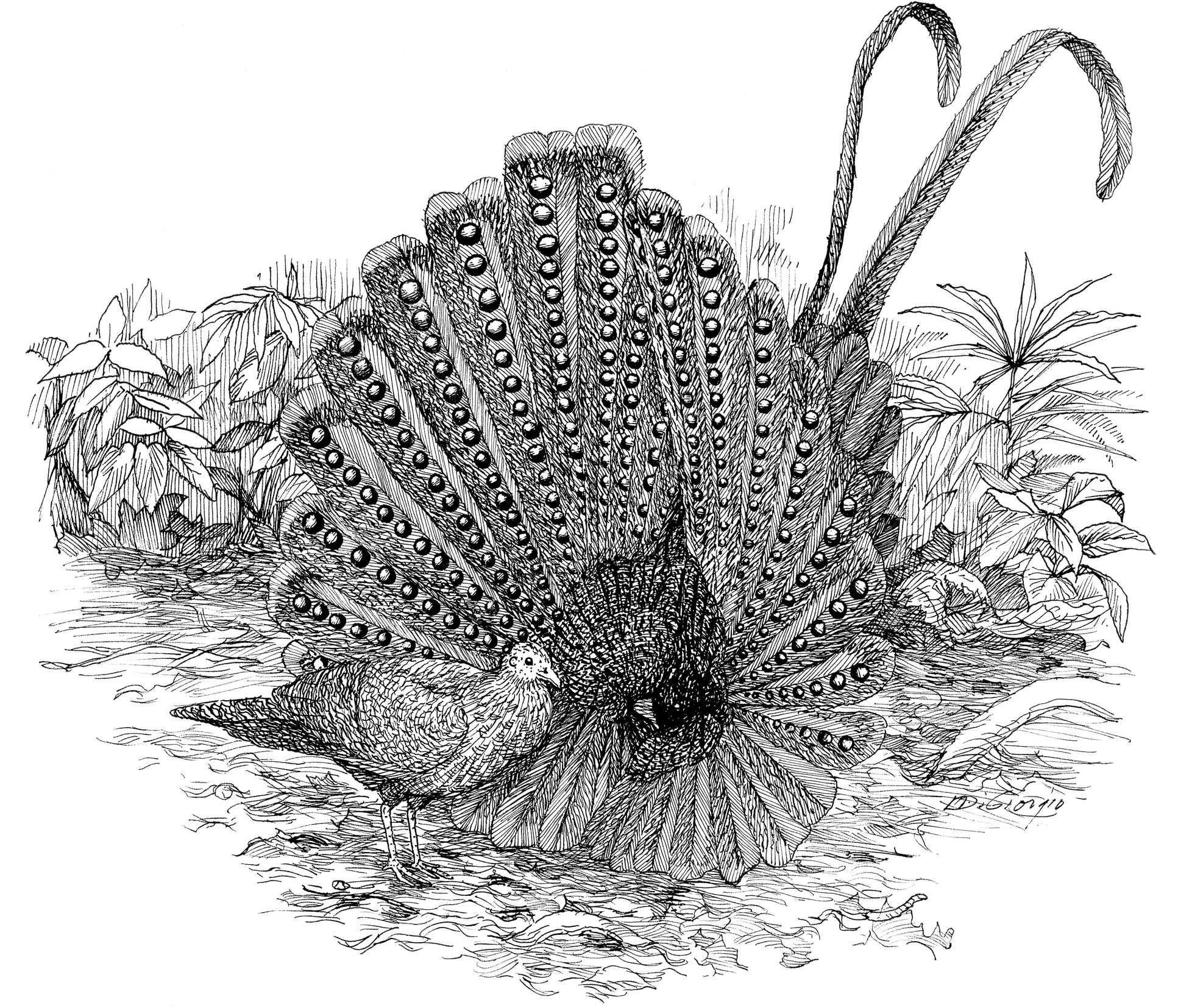

The “frontal movement” display of the male Great Argus.

So far, this description of the male’s theatrical display postures, dramatic as it is, has ignored what is really most remarkable about the “frontal movement” of the Great Argus—the over-the-top patterns on his wing feathers. When he assumes this blown-out-umbrella posture, the male reveals the upper surfaces of the wing feathers, which are largely hidden when his wings are folded and closed. The transformation is unimaginably stunning. Although the hues of his wing feathers are in a subdued palette of black, deep brown, red brown, golden brown, tan, white, and gray, the ornateness and complexity of the pattern in which they are arranged is perhaps the most highly elaborated of any creature on earth. From the tiniest submillimeter-sized dots on individual feathers to the overall pattern of the fully extended four-foot-wide feathery cone, the forty wing feathers of the Argus Pheasant combine to create a paisley effect of such staggering complexity that it simply blows the peacock’s tail away (color plate 3). Nothing else I know in nature can rival the fantastic intricacy of this design.

Each individual feather encompasses all the pattern complexity of a zebra, a leopard, a tropical reef butterfly fish, a flock of butterflies, and a bunch of orchids. The overall appearance is as richly worked as the design of a Persian carpet. Each wing feather is so densely packed with varied zones of dotted, striped, and swirling waves of color that it could rightly merit its own monograph.

The shorter, primary wing feathers, which are attached to the bones of the “fingers” and “hand” at the tip of the bird wing, form the bottom half of the cone. These feathers have dark shafts, light gray tips, and various zones of tan with intricately spaced brown dots or reddish brown with tiny white speckles. But the most celebrated color patterns are found on the secondary wing feathers, which are attached to the trailing bones of the forewing, or ulnas; they create the top half of the feathery cone. Each secondary feather is over three feet long and nearly six inches wide at its tip. The central shaft, or rachis, of each feather is bright white and divides the feather into two halves that are adorned with entirely distinct color patterns. The inner vanes are an array of blackish dots on a gradient of gray. On the outer vane of each secondary feather, the twisted bars of deep brown and light tan (which camouflage the bird so well when the wings are folded at rest) grade into wavy, striped patterns of tan and black. Nearest the rachis on the outer vane is a series of remarkable golden yellowish-brown spheres outlined heavily in black (color plate 4). It is these spheres—often called ocelli or eyespots—that give the species its name. In 1766, Carl Linnaeus named this pheasant after the all-seeing, hundred-eyed giant of Greek mythology, Argus Panoptes. However, the Great Argus has three times as many “eyes” as his namesake!

Twelve to twenty of these lovely golden spheres radiate in a line from the base to the tip of each secondary feather. I refer to these round golden patches as “spheres” because they are exquisitely and subtly counter-shaded, as if by the skillful brush of a painter, to create a stunningly realistic optical illusion of three-dimensional depth. The golden tan at the center of the sphere is outlined from below with a dark, mascara-like smudge, creating the impression of a shadow being cast. On the opposite side of the circle, the golden yellow blends subtly into a bright white crescent that looks like a “specular” highlight—like the shine from the surface of a glossy round apple. As Darwin noted, the color shading on each sphere is precisely oriented so that when the secondary feathers are suspended above and around the female in the giant cone, they produce the startling impression that the golden spheres are three-dimensional objects suspended in space and illuminated from above as if by a shaft of light piercing through the forest canopy. The three-dimensional illusion is further enhanced by the fact that when the male holds these secondary feathers up in the air during the display, ambient light will be transmitted through these unpigmented white highlights, giving them an extra brilliant and luminous quality.

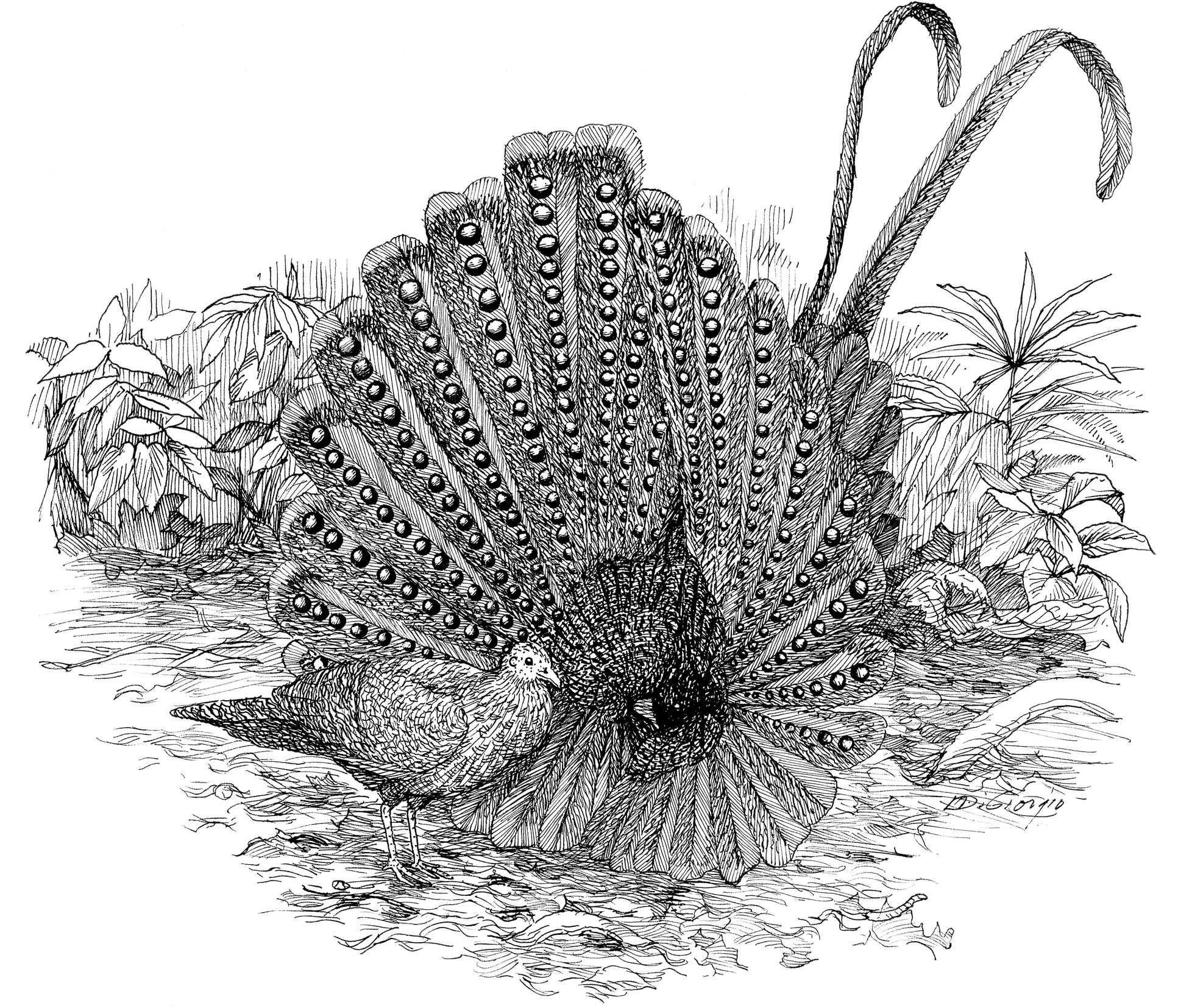

(Left) The “golden spheres” on the male Great Argus secondary feathers gradually increase in size toward the tip of the feather. (Right) A forced perspective illusion makes the spheres appear to be nearly uniform in size when viewed at an angle, similar to the view of the female during the display. Photos by Michael Doolittle.

An additional optical illusion is created by the fact that the golden spheres at the bottom of each secondary wing feather are about half an inch wide at the base and gradually increase in size to over an inch wide at the tip. Because the spots become physically larger the farther they are from the female’s eye, they appear to create a forced perspective illusion in which the spheres appear uniform in size from her point of view.

Taken together, the elements of the male display add up to a sensory experience of mind-boggling complexity—a throbbing, shimmering hemisphere of three hundred vertically illuminated golden spheres that instantaneously appear suspended in the air against a feathery background tapestry of speckles, dots, and swirls. The golden balls emanate outward from the center of the display, where the male’s black eye and blue face can be glimpsed peeking out. The whole effect is magnificent.

How do all these marvelous ornaments impress the female Argus? Observers are unanimous in describing the female’s response as completely underwhelming, or even undetectable. William Beebe wrote, “There is no question in my mind that the wonderful colouring, the elaborate ball-and-socket illusion of the ocelli, the rhythmical shivering of the feathers which makes these balls revolve—all are lost, as aesthetic phenomena, upon the nonchalant little hen.”

In rejecting the possibility that the female Argus is having any aesthetic experience, Beebe exercised an odd kind of reverse anthropomorphism. If we humans find the male’s display to be awe inspiring, shouldn’t the “little hen” exhibit a stronger, visible response to it? Shouldn’t she be acting more like how we feel? Maybe because Beebe had spent months in the jungle trying to observe this display and many weeks huddled in his various hideouts, he expected the female Argus to evince at least some of the excitement that he himself experienced when he finally saw the display from his muddy foxhole. His conclusion that she did not share his excitement led him to be skeptical of the possibility that the male’s display had any aesthetic impact on her at all. However, sexual selection theory holds that every elaborate ornament is the result of an equally elaborate, coevolved capacity for aesthetic discernment. Extreme aesthetic expression is always a consequence of extreme rates of aesthetic failure—that is, rejection by potential mates. Male Argus have such extreme ornaments precisely because most males are not chosen as mates. Thus, a calm, under-impressed female Argus is actually acting as we should expect—more like an experienced, well-educated connoisseur evaluating one of the many extraordinary works available to her scrutiny than an excited naturalist having a once-in-a-lifetime encounter. And from what I’ve seen of videos of these courtship performances, that’s exactly how I would describe her—rigid with highly focused attention as she casts her discerning eye over the displaying male. The female Argus may appear dispassionate as she watches the male’s efforts, but it’s her coolheaded mating decisions over the course of millions of years that have provided the coevolutionary engine that has culminated in the male Argus’s display of hundreds of golden balls shimmering and gyrating in the air.

The magnificent feathers and elaborate displays of the Great Argus have long been a prime piece of evidence in our struggle to understand the origin of beauty in nature, but this evidence has led thinkers to diametrically opposite conclusions. In his 1867 antievolution tract, The Reign of Law, the Duke of Argyll cited the “ball and socket” designs of the Great Argus wing feathers as a sign of God’s hand in creation. Darwin countered that the Great Argus is evidence of the evolution of beauty by mate choice, concluding that “it is undoubtedly a marvelous fact that the female [Great Argus] should possess this almost human degree of taste.”

During the century-long intellectual eclipse of mate choice theory, biologists were hard-pressed to explain the reason for aesthetic extremities like those of the Great Argus. William Beebe described Darwin’s theory as intellectually tempting—“Darwin’s ideas are those which we human beings would prefer to accept”—but ultimately unpersuasive. Given his low opinion of the cognitive and aesthetic capacities of female pheasants, Beebe simply could not accept the idea of sexual selection: “It seems impossible to conceive, much as we would like to believe in it, and personally, I should be willing to strain a point here and there to admit this pleasant psychologically aesthetic possibility; but I cannot.”

Then how did Beebe explain the evolution of the male Great Argus? He could not. He concluded, “It is one of those cases where we should be brave enough to say, ‘I do not know.’ ” Ironically, a man who spent years of his life tracking down the displays of this fabulously beautiful creature, and many other pheasants, found Darwin’s explanation for its beauty “impossible.” This is a real measure of the intellectual loss that followed in the wake of Wallace’s rout of Darwin’s theory of mate choice.

Today, however, all biologists embrace the fundamental concept of mate choice. Thus there is complete consensus that the ornamental plumage and behavior of the Great Argus have evolved through the agency of female sexual preferences and desire—that is, sexual choice. We now agree that ornament evolves because individuals have the capacity, and the freedom, to choose their mates, and they choose the mates whose ornaments they prefer. In the process of choosing what they like, choosers evolutionarily transform both the objects of their desires and the form of their own desires. It is a true coevolutionary dance between beauty and desire.

What biologists don’t agree on is whether mating preferences evolve for those ornaments that provide consistently honest, practical information—about good genes or direct benefits like health, vigor, cognitive ability, or other attributes that would help the chooser—or whether they are merely meaningless, arbitrary (albeit fabulous) results of coevolutionary fashion. Actually, most biologists are in agreement with the former hypothesis. I am not. More precisely, I think that adaptive mate choice can occur but it is probably rather rare, whereas the mechanisms of mate choice envisioned by Darwin and Fisher, and modeled by Lande and Kirkpatrick, are likely to be nearly ubiquitous.

But it nonetheless remains true that since Darwin’s Descent of Man the beauty-as-utility argument has been rampantly successful. The purpose of this chapter is to show how this flawed consensus persists. It persists in large part because it has been propped up by an unscientific faith in the ultimate validity of its own conclusions.

In 1997, I submitted a manuscript to the American Naturalist, a first-class science journal in ecology and evolutionary biology. The paper discussed both the arbitrary and the honest advertisement mechanisms of mate choice to try to determine which were operative in the evolution of certain avian courtship displays I had observed. In one section of the manuscript, I discussed a specific sequence of display behavior within a group of birds called manakins (which I discuss further in chapters 3, 4, and 7). Through a comparative examination of the display behaviors of multiple species within the group, I described how the males of one of the species, the White-throated Manakins, evolved a novel bill-pointing posture that replaced an ancestral tail-pointing posture that had been a routine part of the standard display repertoire. It was as though evolution had edited out the old posture with a cookie-cutter and pasted in the new one in the same exact position within the behavioral sequence. I proposed that this change was unlikely to have evolved because it provided better information about mate quality—if it did, then all of the manakin species would have evolved it—and more likely to have evolved in response to arbitrary, coevolved aesthetic mate preferences.

In science, journal editors send your work out to anonymous peer reviewers—other scientists who often include your intellectual competitors. The reviewers’ comments on the work are used by the editor to help decide whether the work should be published and to guide the author on improvements to the work. In this case, the anonymous reviewers hated this section of the paper. They argued that I could not state that this new posture had evolved through arbitrary mate choice because I had not specifically rejected each of the many adaptive hypotheses that they could imagine. For example, I had not tested whether the bill-pointing White-throated Manakin males were revealing their superior vigor or disease resistance. I responded that standing motionless in one posture as opposed to another was unlikely to be able to communicate any additional information about vigor or genetic quality, unless we were to hypothesize that the tail-pointing posture in the ancestral birds had evolved in order to reveal whether they were infested with butt mites, and the bill-pointing posture must have evolved in order to reveal the possibility of some more recent problem in evolutionary history, such as infestations of throat mites. This seemed unlikely to me, but the reviewers insisted that the burden of proof was on me to demonstrate that the display traits were arbitrary. Of course, this made it impossible to “prove” my point, and I ultimately cut this section out of the manuscript in order to publish the paper.

This exchange continued to bother me long after the paper appeared in 1997. How many of these adaptive hypotheses, I wondered, would I have to test before I could conclude that any given display trait was arbitrary—that is, that it lacked information about any quality other than its attractiveness? When would I ever be done with this task? Even if I were able to test every adaptive explanation they could think of, pleasing one set of reviewers would only be the first of my hurdles. Their reasoning implied that I would have to test other hypotheses in order to satisfy other skeptical reviewers, and then others, ad infinitum. Because there would be no end to the creative imaginations of the reviewers, there would be no end to the process of trying to demonstrate that any specific trait is arbitrary. I was trapped. The prevailing standard of evidence meant it would be impossible for me to ever conclude that any trait had evolved to be arbitrarily beautiful. It had actually become impossible to be a contemporary Darwinian.

I realized that it was Alan Grafen’s standard of evidence that had put me in this bind: “To believe in the Fisher-Lande process as an explanation of sexual selection without abundant proof is methodologically wicked.”

Of course, Grafen was not the first to deploy the “abundant proof” standard, which has a long, respected history in science. In the 1970s, in regard to paranormal psychology, Carl Sagan claimed, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” This famous “Sagan Standard” can actually be traced back to the French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace, who wrote, “The weight of evidence for an extraordinary claim must be proportioned to its strangeness.”

Thus, whether Grafen’s abundant proof standard should be invoked depends on our perceptions of the strangeness of the Darwin-Fisher theory of mate choice. But what dictates the strangeness of a hypothesis? Should we allow our gut feelings about the way the world should work to dictate our scientific investigation of the way it does? Grafen argued that the comforting “rhyme and reason” of Zahavi’s handicap principle should compel us to reject the terrible strangeness of arbitrary mate choice.

Of course, it’s human nature to want to believe in a universe that is rational and orderly. No less a scientist than Albert Einstein backed away from quantum mechanics—for which he had laid much of the intellectual groundwork himself—because it brought uncertainty and unpredictability into the world of physics. In rejecting quantum mechanics, Einstein famously wrote, “God does not play dice.” But eventually quantum mechanics triumphed despite its enduring strangeness, because the predictive power of the theory was too great to ignore. Our understanding of the physical laws of the universe has progressed immeasurably since then. Physics was forced to embrace a stranger universe.

Unfortunately, it has been difficult to dislodge the taste for “rhyme and reason” in evolutionary biology. In mate choice, the longing for rhyme and reason has left us with a tired, worn-out science that consistently fails to account for the evolution of beauty in the natural world. The current adaptationist “consensus” rests on surprisingly weak foundations. To get to the heart of what is wrong with it, we have to explore the basics of the scientific process.

When we test a scientific hypothesis, we must compare a conjecture—say, that a specific mechanism is responsible for producing the observations that we have made of the world—with a more general conjecture that nothing special is happening; that is, no specific, or special, explanation is required to account for the observations we have made. In science and statistics, this “nothing special is happening” hypothesis is known as the null hypothesis, or null model. In an incredibly pleasing and serendipitous coincidence that has no influence whatsoever on the validity of my argument, the concept of the null hypothesis was actually invented in 1935 by none other than Ronald A. “Runaway” Fisher, who coined the term and described it this way: “We may speak of this hypothesis as the ‘null hypothesis,’ and it should be noted that the null hypothesis is never proved or established, but is possibly disproved, in the course of experimentation.”

Thus, before we can assert that some specific process or mechanism of interest is happening, we must first reject the null hypothesis that nothing special is happening. The rejection of the null results in an affirmative conclusion that something distinctive is, indeed, going on. But, as Fisher observed, the null hypothesis is intellectually asymmetrical. One can find evidence to reject the null hypothesis, but one can never really prove it. In other words, given the logical structure of scientific inference, it is possible to provide enough evidence to establish that something special is happening but impossible to definitively establish that nothing special is happening.

Of course, the null hypothesis is more than just a temporary intellectual tool that we deploy to get a scientific job done. Sometimes, it is actually an accurate description of reality. Sometimes, “nothing special” really is happening! And when the null is an accurate description of the world, its function is to prevent science from going off on unsupportable flights of fancy. Null hypotheses actually protect science from its own crazy conjectures and faith-based fantasies.

Unfortunately, there are fundamental reasons why humans, including professional scientists, are biased toward thinking that something special must be happening. The human brain gets lots of rewards for detecting hard-to-see patterns in the flow of sensory information and cognitive details. Being able to figure out what’s going on when it’s not obvious is perhaps the most fundamental advantage of intelligence. Think, “I see the fresh tracks of the water buffalo in the mud. I’ve noticed that they come here to drink every morning. If I come early tomorrow morning and hide behind that bush, I can kill one to eat!” But the cognitive capacity to interpret the world as filled with meaning and governed by rational cause and effect can also guide us to mistaken conclusions, convincing us that something special must be going on when in fact nothing specific is happening. Ghost stories, miracles, magic, astrology, conspiracy theories, hot streaks in sports, lucky dice, or team curses are all examples of the boundless human desire for explanatory rhyme and reason where none is required.

Lots of people indulge in their irrational desires for meaningful explanations of our chaotic world, often in ways that are so mainstream that it never occurs to us to wonder about their validity. For example, an entire industry of business news provides continuous explanations of what’s going on in economic marketplaces when in all likelihood there is absolutely nothing special going on most of the time. Business news channels broadcast an endless stream of financial reports about “events” in global financial markets. They confidently explain that the Hang Seng Index is up, or the London FTSE is down, or Dow futures are unchanged because of the latest unemployment report, negotiated sovereign debt settlement, or quarterly profit reports. Of course, the null hypothesis is that market activities are the result of the aggregate effects of millions of independent decisions by individuals who are each trying, as John Maynard Keynes memorably stated, “to guess better than the crowd how the crowd will behave.” But the null model that market fluctuations lack a common or generalizable external cause is never entertained on the business news. This may be because business news is, after all, a business itself. Honest reporting of the null hypothesis would be very bad for their bottom line. Audiences are unlikely to tune in following a null news promo: “Random stuff happened on Wall Street today! Details at twenty past the hour!” The business news reporters assume that everything is the result of some rhyme and reason and that their job is to report that as true, even if it has to be invented.

Null hypotheses are essential to science, even when they are horribly wrong, because it’s only in the attempt to find evidence to reject them that a better understanding emerges. For example, “cigarettes do not cause lung cancer” is a null hypothesis. According to this null, lung cancer has many diverse causes, and smoking has no generalized effects on lung cancer risks. Many people do smoke cigarettes, and many smokers do get lung cancer, but according to the null there is no causal association here. Interestingly, in the 1950s, Ronald A. Fisher was an enthusiastic and energetic public advocate of this particular, dismally incorrect null hypothesis, which has since been definitively disproven. Another, more contemporary null hypothesis is “global warming is not caused by the human production of atmospheric greenhouse gases.” The job for the scientist in such instances is to prove the null hypothesis wrong by gathering the requisite evidence to reject it. In other words, the scientific burden of proof always lies with those who want to show that something specific is happening, not on those who think that it is not.

After years of struggling against Grafen’s abundant proof standard, I came to realize that the field of evolutionary biology had become like the financial market news reports. Evolutionary biologists have become convinced that a special kind of rhyme and reason—adaptive mate choice—must be happening everywhere and all the time. Why are they so convinced? When you examine it, it is mostly just a belief that the world must be that way. Remember, in rejecting Darwinian mate choice, Wallace asserted as a matter of principle that “natural selection acts perpetually and on an enormous scale.” The intellectual justification remains largely unchanged.

Despite its enduring strangeness to many, the Lande-Kirkpatrick sexual selection mechanism is not merely an alternative hypothesis to adaptive mate choice; it is the appropriate null model for the evolution of sexual display traits and mating preferences. It describes how evolution by mate choice works when nothing special is happening—that is, when mates are choosing what they prefer, period. Because evolution requires genetic variation to occur, the Lande-Kirkpatrick model assumes genetic variation in trait and preference. But it does not assume that mates vary in quality, that any display traits are correlated with that quality, or that mating preferences are under natural selection to prefer those traits. That is why it is the null model.

If the Lande-Kirkpatrick mechanism is the appropriate null model for evolution of traits and preferences, then it cannot be proven. Thus, Grafen’s demand for “abundant proof” of the Fisher-Lande process was so rhetorically effective precisely because it demanded the impossible. Checkmate! This was the trap I experienced when I realized that I could never satisfy my reviewers. And this is why, nearly 150 years after The Descent of Man and 25 years after Grafen’s 1990 paper, there are still no generally accepted, textbook examples of arbitrary mate choice. Period. Grafen’s gambit triumphed.

The contemporary science of mate choice is a case study in the intellectual pitfalls that can befall a science that does not incorporate any null hypothesis or model. In the absence of a null model, adaptive mate choice is unscientifically protected from falsification. It becomes the preordained answer to every question about the evolution and function of an aesthetic trait. When a trait can be shown to be correlated with good genes or direct benefits, the adaptive model is declared to be correct. When no such correlation is found, the result is interpreted merely as a failure to try hard enough to establish how the adaptive model is correct. In this framework, the ultimate research goal for every young scientist or graduate student is to demonstrate what everyone already knows to be true in some delightfully unexpected, new way that no one has ever imagined before. Because it has been embraced for the comforting rhyme and reason it provides, the entire adaptive mate choice enterprise has devolved into a faith-based empirical program to generate evidence to confirm a generally agreed-upon truth. The function of null models is to prevent this kind of faith-based confirmationism from taking over science.

“Stuff happens.” The phrase may sound ridiculous or even flippant, but in its simplicity it actually captures the essence of the null model. Within the context of evolution through mate choice, we can restate this null as “Beauty Happens.” (Remember, we mean beauty as the animal perceives it.) As the null model for the origins of aesthetic traits in nature, Beauty Happens provides an invigorating new perspective on the evolution of sexual beauty. It’s a slogan that I think Darwin would have both understood and embraced.

At this point, it is important to emphasize again that a fully aesthetic theory of mate choice includes the possibilities of both the arbitrary null model (Beauty Happens) and the adaptive mate choice model (honest indicators of good genes and direct benefits). After all, a Maserati or a Rolex can be aesthetically pleasing while also performing utilitarian functions like driving at race car speeds or keeping accurate time. Thus, the aesthetic perspective is inclusive of other possible explanations for the evolution of specific display traits. The adaptive view, by contrast, does not allow for the possibility that arbitrary Fisherian mate choice occurs. It is the very opposite of inclusive.

How should the science of mate choice proceed from here? When looking at a given sexual ornament or display behavior, we must ask this basic question: Has the trait evolved because it provides honest information about good genes or direct benefits or because it is merely sexually attractive? Only by first disproving the null model that Beauty Happens can this scientific research program make progress.

The science of mate choice needs a null model revolution. Although researchers who joined the field in order to pursue their interests in adaptation will not find this message comforting, we have good evidence from other fields of evolutionary biology that null model revolutions are both successful and intellectually productive, even for adaptationists. In molecular evolution, a null model revolution in the 1970s and 1980s led to the universal adoption of the neutral theory of DNA sequence evolution. Now, before one can claim that certain DNA substitutions are adaptations, one must reject the null hypothesis that such changes are merely neutral variations that evolved by random drift in the population. In community ecology, a null model revolution in the 1980s and 1990s led to the universal adoption of null models of community structure. Now, before one can claim that an ecological community has been structured by competition, one must first reject a random, null model of community composition. In both fields, even the most ardent natural selectionists have ultimately embraced null and neutral models, because they advance their ability to test and support hypotheses of adaptation. It is critical that the science of evolution embrace a null model of sexual selection.

Opponents of adopting null and neutral models in evolutionary biology sometimes complain that the proposed null models are too “complex” to be an appropriate null model. To them, null models should be simpler and more parsimonious. But this view misconstrues the intellectual function of the null model. For example, if cigarettes cause lung cancer, then the causal explanation of most lung cancers is actually quite simple—cigarettes. If the null hypothesis that cigarettes do not cause cancer were true, then the actual causes of lung cancers would be much more variable, individualized, and complex. So null models are not necessarily simpler explanations. Rather, the null model is the hypothesis that the proposed, generalized causal mechanism is absent. In evolution, that critical causal mechanism is natural selection, which is why the Beauty Happens hypothesis is the appropriate null.

With an understanding of what is at stake if we forgo the null model, we can return to a consideration of the male Great Argus. First, we need to grapple with the full breadth of the aesthetic complexity that requires evolutionary explanation. The totality of the sexual ornaments in the Great Argus includes the male territory and court-clearing behavior, court attendance, vocalizations, the diverse display repertoire including each of his movements, the facial skin color, and the size, shape, patterning, and pigmentation of each feather. The full display behavior of the Great Argus is like an opera or a Broadway musical. It consists of music, dancing, elaborate costumes, lighting, and even trompe l’oeil effects, albeit on an intimate stage with a solo cast.

One way to try to think about this aesthetic complexity is to conceive of each and every detail as an evolutionary design “decision.” How many total decisions would be required to describe the “Full Monty” of the Great Argus? Starting at the tip of one primary wing feather, we see that the broad tip of the feather is gray, not brown, with large dots that are reddish brown, not white, tan, or black. Toward the base of that same feather, the background color changes to tan, but the dots stay the same color, become smaller, get closer together, and then converge into a true honeycomb pattern. Each and every one of these details could be different. Indeed, every one of these details is different in every other species of bird in the world. Evolutionary biologists who believe that natural selection dictates the form of various display traits are not only required to describe the mere existence of ornament; they are charged with explaining the origin and maintenance of each and every specific detail of its form. In the case of the Great Argus, the number of independent aesthetic dimensions adds up to hundreds or even thousands—a practically unfathomable degree of complexity.

The adaptive mate choice paradigm asserts that each and every one of these features has specifically evolved as an honest indicator of good genes or direct benefits. In other words, each detail evolved as it did because it was better at providing quality information than all other available variations. Most mate choice researchers see their job as demonstrating how this is true, not testing whether it is true. Without a null model that allows one to reject the adaptationist account, they cannot do otherwise. In any given study, researchers will measure multiple aspects of male ornament and try to correlate them to the health and genetic information they are presumably providing, but at best only one or a few of the many aesthetic features of the full display repertoire will show any sign of a correlation with mate quality. Biologists then use this very limited subsample of their data to draw general conclusions about the role of honest signaling in the process of sexual selection as a whole. The vast majority of the data inevitably fail to confirm the adaptive theory of mate choice. As a result, the vast majority of the ornamental details remain unexplained even as the adaptive explanation of mate choice triumphs.

We will never establish a satisfactory explanation of evolution by studying only those data that turn out to “work” the way the researcher hopes. Because those investigations that are not able to confirm the adaptive value of any ornamental features are considered failures—failures to work hard enough to find the data to demonstrate how adaptive mate choice is true—such studies don’t get published. In this way, the current paradigm prevents us from ever seeing these data, which are actually a legitimate description of the way the world is, and how it got that way. Indeed, they are exactly consistent with the Beauty Happens model. In this way, the adaptationist worldview can make us blind to the true nature of reality. And this blindness certainly affects our ability to “see” the Great Argus.

Unfortunately, studying mate choice in the Great Argus in the wild would be extremely difficult. Recall that G. W. H. Davison observed males for seven hundred hours over three years and only managed to witness one female visit. He saw no copulations. Perhaps if one could find dozens of Argus nests, one could use DNA analyses of the chicks to identify all their fathers. However, one would also have to place arrays of hidden cameras at multiple male courts to record the patterns of female visits and the variations in display behavior among successful and unsuccessful males. And one would need to capture these males and record information about their health, condition, and genetic variation. It would be a huge and expensive undertaking.

Setting aside the difficulty in obtaining these data from the wild, let’s consider whether female pheasants might be gaining either of the two kinds of adaptive benefits from their mate choices. The most fundamental benefit is good genes—heritable genetic variations that would endow the female’s offspring, both male and female, with survival and fecundity advantages.

Although the good genes hypothesis has had a good run in intellectual history and remains popular, empirically it has fallen on hard times. Many studies have failed to find any evidence of a correlation between good genes and female sexual preferences. For example, a recent “meta-analysis”—that is, a big statistical study of multiple data sets from many independent investigations of different species—did find significant evidence in support of arbitrary Fisherian mate choice while failing to find support for the idea that males who are preferred provide any good genes. These results were based on the scientific literature, which is likely to have a publication bias toward the publication of “positive” results—that is, results that support good genes. As discussed, “negative” results are more frequently considered scientific failures and consigned to the rubbish heap. Thus, the failure of meta-analysis to find support for good genes is probably just the tip of the data iceberg. The vast volume of data remains unseen, lurking below the surface, and this giant bolus of unpublished, privately held data is likely to be overwhelmingly negative. It’s becoming more and more apparent that good genes is an intriguing idea that is failing to find much support in nature.

The other adaptive benefit that Great Argus males may provide to females that choose them as mates is in the form of direct benefits, which accrue to the survival and fecundity of the female herself. In monogamous birds that form social pairs to raise their young, these direct benefits may include defending a shared territory rich in high-quality resources, helping with parental care, defending against predators, and making other contributions to a successful family life. But the male Great Argus provides no parental care or reproductive investment whatsoever. He merely provides sperm. Because females mate and leave immediately to incubate their eggs and raise their young on their own, their interactions with males are limited to the visits they make to various males in order to choose their mates and the brief moment of copulation that ensues once they’ve made their choice. Thus, they have only two possible ways of obtaining any direct benefits whatsoever from male Great Argus. First, preferred males could be those with display signals that make female mate choice more efficient, minimizing the investment of time and the risk of predation incurred during the female’s visits to the males. However, there is nothing remotely efficient about what’s involved in assessing the Great Argus display. The female must travel widely (probably miles) to visit different males, and she must observe each one at a really intimate proximity in order to properly observe his display. The other possibility is that male displays could be providing honest information about their lack of infection by sexually transmitted diseases. However, this seems highly unlikely as well. Selection to avoid sexually transmitted disease would result in strong natural selection against the polygynous breeding system, which would greatly foster STD transmission, and not to selection for extreme coevolved aesthetic traits and preferences.

In conclusion, even without further data from the wild, there are excellent reasons to think that the Great Argus is an evolutionary example of the Beauty Happens mechanism.

Another intellectual hurdle for adaptive mate choice is the sheer complexity of the Great Argus display. According to the handicap principle, the honesty of any display is ensured by the costs it imposes on the individual. These costs include both the developmental costs of making it and the survival costs of having it. But the costs of signal honesty create another burden to an adaptive explanation of the many multiple ornaments in the Great Argus display repertoire. According to the theory, each of these ornamental dimensions must provide an independent channel of quality information in order to sustain the additional costs that ensure its honesty. If some costly ornamental detail within a repertoire does not provide some independent information about quality, then it would either never evolve or be eliminated by natural selection as redundant and superfluous. Thus, the handicap principle establishes real constraints on the evolution of aesthetically complex repertoires of multiple display traits. Yet aesthetic complexity is present not just in the Great Argus but throughout nature.

Of course, multi-trait repertoires with many independent ornamental dimensions pose no challenge at all to the Beauty Happens evolutionary mechanism. Indeed, the model predicts them. Given free rein, mate choice is likely to produce evolutionary runaways in the complexity of the repertoire of ornaments as well as in the complexity of any individual ornaments.

Some honest advertisement theorists have proposed that complex ornamental repertoires could function as adaptive multimodal displays. In this view, the Great Argus aesthetic repertoire is like a Swiss Army knife; each aspect of the display is a different adaptively optimized blade for a distinct communication task within the general mission of honest and efficient mate attraction. Each display communicates a distinct channel of quality information through a specific sensory modality. The concept of “multimodal” display is an attempt to flatten aesthetic complexity into a manageable set of individualized, rational utilities. But it doesn’t avoid the problem of multiple redundant costs.

Before we go further, however, we should ask, “Is this even possible?” How many independent channels of mate quality information are there for the female to evaluate? It is hard to know because no one, as far as I know, has ever asked this question before. However, I think there are a few relevant ways to think about it. If you wanted to accurately evaluate the health and genetic quality of a human being, how would you go about it? This is, in part, what doctors try to do during regular checkups. How much can you tell about a person’s future health from the results of an annual physical examination? Well, the American Academy of Family Physicians has recently determined that beyond routine weight and blood pressure monitoring, there is no evidence of the medical effectiveness of regular physical examinations. Except for the assessment of body weight and blood pressure, a doctor’s observations do not detect enough information relevant to future health outcomes with sufficient frequency to make annual checkups cost-effective. Of course, a doctor’s exam involves asking a lot of specific questions and the use of many invasive procedures—like blood tests—that are not available to female Great Argus as they evaluate potential mates. Female pheasants do not have sphygmomanometers, stethoscopes, or EKG machines. Yet even with all our equipment and our advanced medical knowledge, regular detailed inspection of the human body and verbal interviews are not able to provide sufficiently useful information about human health outcomes to make them worth doing.

The truth is that it is very difficult to accurately assess the genetic quality of an animal and predict its future health even with advanced knowledge and scientific tools. Can we expect the female Great Argus to be able to make better assessments of the health of their potential mates than human physicians?

But let’s go further than your typical family physician and imagine that we can sequence the entire genome of every individual patient. What can we learn from information about potential health risks to those individuals from their genomes? Well, we can learn about the possibility of developing rare diseases that are caused by single genes like cystic fibrosis and Tay-Sachs. But we would learn surprisingly little about the risks of any of the complex diseases that cause most deaths—like heart disease, stroke, cancer, Alzheimer’s, mental illness, or drug addiction. Indeed, since the early years of the twenty-first century, the juggernaut of initiatives in genomic medicine has been hampered by the failure of the genomic data to provide much predictive information about any complex diseases. For example, it is easy to find dozens of genetic variations that are significantly associated with heart disease. But, except for a few rare genetic variations that are particular to certain ethnic groups, when the effects of all these genes are added together, they explain less than 10 percent of the heritable risk of heart disease. So, even with complete genomic information, predicting genetic quality and future health outcomes is fundamentally challenging. This fact is why the Food and Drug Administration, in 2013, prohibited personal genomic companies like 23andMe from marketing information to their customers about their genetic risks of disease without specific approval. Most of the statistical associations between single genes and disease are currently so vague and tenuous that reporting such information to customers was considered fundamentally misleading.

So again we must ask, is it likely that a female Great Argus could draw any more valid conclusions about the genetic suitability of a potential mate than a scientist armed with complete genomic information? Of course, it’s theoretically possible that she might be able to do this, but this is an empirical issue that should actually be investigated, not accepted on blind faith. The failure of human genomic medicine to find reliable tools to predict most complex health outcomes is highly relevant to the good genes hypothesis, providing even more reason to be skeptical about the prospect of assessing adaptive value of a mate from every ornament.

The intellectual collapse of one infamous honest signaling mechanism provides amusing insights into the social phenomenon of mate choice science. In papers published in 1990 and 1992, the Danish evolutionary biologist Anders Møller proposed that body symmetry reveals an individual’s genetic quality and that bilaterally symmetrical displays evolve through adaptive mate choice for higher-genetic-quality mates. Møller’s data indicated that female Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica) prefer males with the longest and most symmetrical outer tail feathers. Soon, there was a burgeoning cottage industry supporting mate choice based on symmetry in a wide variety of organisms.

Ironically, like an irrational Fisherian runaway, the idea of symmetry as an honest indicator of genetic quality got ever more popular, merely because it was so popular. One scientist who was excited by the idea and attempted to replicate its findings in his own research was distressed to find that he could not do so. “Unfortunately, I couldn’t find the effect,” he was quoted as saying in a New Yorker article published in 2010. “But the worst part was that when I submitted these null results I had difficulty getting them published. The journals only wanted confirming data. It was too exciting an idea to disprove, at least back then.” The adaptationist confirmation bias at work once again.

But in the late 1990s, support for the idea that symmetry indicates genetic quality suddenly began to wane. A few critical papers came out, and then a few more. By 1999, meta-analyses of multiple data sets showed that support for the idea had simply evaporated.

Of course, scientists are loath to admit that they are slaves to fashion like everyone else. So, contemporary reviews of mate choice in the animal kingdom rarely even mention this embarrassing episode. Yet the enthusiasm for honest symmetry is such a prime example of bandwagon science that it was prominently featured in the New Yorker article, mentioned above, about the sociology of failure in science. Unfortunately, it still lives on in adaptive theories of human sexual attraction, neurobiology, and cognitive science. You would think that, decades on, news of its collapse and discredit would eventually reach the evolutionary psychology researchers who continue to preach it. But the “honesty of symmetry” has become a zombie idea—an idea so attractive that it lives on and on despite being repeatedly falsified.

In any case, the symmetry hypothesis could never have provided more than a very partial explanation of the evolution of complex ornaments like the patterns on the Great Argus’s wing and tail feathers. Even if it did exist, natural selection for perfectly symmetrical signals would fail to explain any of the myriad other specific and complex details within the Great Argus’s plumage and display.

A newly emerging adaptive mate choice hypothesis takes a page right out of Wallace’s critiques of Darwin. It has recently been proposed that elaborate courtship displays evolve in order to indicate male vigor, energy, and performance skill to their prospective mates. Accordingly, females prefer such displays because they raise the male’s heart rate, exhaust his energy reserves, or push him to the limits of his physiological capacity. The best dances indicate strong, fit fellows. Unfortunately, this popular idea fails in several ways to explain specific details of complex display repertoires like that of the Great Argus. There are many imaginable displays that would create far greater physiological challenges to the male than his relatively low-energy performance. So why haven’t more extreme tests of his physiology evolved instead?

Of course, I acknowledge that the males of many species do engage in displays that are physiologically demanding. But the fact that physiological costs are incurred does not mean that those costs are honest indicators of quality. Display traits evolve to a balance between natural and sexual selection advantages, and this equilibrium may be far from the optimum for either health or survival. When Beauty Happens, costs will happen too.

The question is whether the physiological challenges are incidental consequences of extreme aesthetic performance or the entire point of the display. By analogy, do people like the extraordinary leaps, pirouettes, and so on of ballet dancers because such performances push the performers to the limits of their physiological and anatomical capacities? Or do performers encounter these physiological challenges in the process of producing art that audiences enjoy? Do we value these feats of physical skill because of their aesthetic effect on us? Or because the effort of achieving them requires that many ballet dancers will experience painful and debilitating foot and leg injuries?

There is no reason to believe that the love of ballet, or of any other human art form, is based on how much pain and effort they cost to the performers. Likewise, there is no reason to believe that the female of the Great Argus or any other species chooses a mate because of how much he endures in the course of his courting performance. It is always the artfulness of the performance that matters; the physiological demands of producing it are secondary. To believe otherwise is to confuse evolutionary cause and effect. Last, just as in the Great Argus, there are many more costly performances that we can imagine that are not preferred. By analogy, atonal twentieth-century concert music, from Berg to Boulez, is incredibly difficult for performers to play well, but that doesn’t make audiences like it.

An interesting way to understand the Darwin/Wallace debate about mate choice is to compare the value of beauty to the value of money. Under the old “gold standard,” the value of a dollar existed because each dollar could be redeemed for a tiny piece of gold. The value of a dollar was extrinsic; dollars had value because they stood for something else of value—that is, gold. By the mid-twentieth century, however, economists and governments realized that the value of money is merely a “social contrivance.” Today, the value of a dollar is intrinsic; dollars have value because people in general agree that dollars have value. There is no gold behind them.

The adaptationist view of beauty works like the gold standard. Accordingly, beauty has no value in and of itself; its value only arises because beauty stands for other extrinsic values, either good genes or direct benefits. In contrast, the Darwinian/Fisherian view of beauty works like all modern currencies. Beauty has value only because animals have evolved to agree that it has value. Its value is intrinsic, and it can evolve for its own sake. Beauty, like money, is a “social contrivance,” and the Lande-Kirkpatrick null model is the mathematical description of that process.

Hard-core advocates of a return to the gold standard, called goldbugs, still believe that the abandonment of the gold standard was a reckless and immoral flight from reason. Like evolutionary goldbugs, neo-Wallaceans are certain that behind every sexual ornament there must be an evolutionary pot of gold, filled with good genes or direct benefits to mate choice, and they defend this view as simple rhyme and reason. Like goldbugs, neo-Wallaceans are quick to label other views as “wicked.”

This analogy also provides insights into why Beauty Happens is the appropriate null model of evolution by sexual selection. Imagine that the next time you see a beautiful rainbow, a small, green-suited leprechaun suddenly appears and promises you that there is a pot of gold at the end. Ask yourself, “What is the null hypothesis?” Obviously, the null hypothesis is that the value of the rainbow is intrinsic and that there is no gold at its end. And until you find that pot of gold at the end of the rainbow and can reject the null hypothesis, you have to stick with it. Likewise, adaptive mate choice posits that behind each and every sexual ornament is a pot of evolutionary gold laden with good genes and direct benefits. What’s the null hypothesis? Obviously, the null hypothesis is that there are no good genes or direct benefits until you can prove that there are. The burden of proof lies with those who believe in adaptive mate choice. Some of those ornaments will indeed be found to be signals of quality. Others (most, in my opinion) will not. We should no more place our trust in evolutionary leprechauns than we do in little green-suited ones!

There are other similarities between the science of mate choice and the “dismal science” of economics. Both disciplines have active debates about the nature and importance of “market bubbles.” The last decades of the twentieth century saw the development of a new, American-style capitalism characterized by increasingly complex mathematical models of investment and risk management and the systematic dismantling of the regulatory controls that had curbed some of the riskier behaviors of financial institutions. The result was supposed to be an unprecedented new era of global growth and prosperity. What happened instead was the global financial crisis in 2008. Obviously, something went fundamentally wrong with the economic model that was expected to prevent such instability. How did economists get this so wrong?

At the core of this failure was the a priori belief in a powerfully rational idea, the efficient market hypothesis, which states that, given open access to accurate information, free markets will always establish the true, correct value of an asset. According to the efficient market hypothesis, economic bubbles are impossible. Sound familiar? As the economist Paul Krugman concluded, “The belief in the efficient market hypothesis blinded many if not most economists to the emergence of the biggest financial bubble in history.”

I think that most evolutionary biologists are equivalently blind to the reality of arbitrary mate choice.

To explore the parallels between the science of mate choice and the business cycle, I had lunch one day with my Yale colleague and neighbor Robert Shiller, the Nobel Prize–winning economist. A well-known expert on housing markets and an advocate of behavioral economics, Shiller was dubbed “Mr. Bubble” in a 2005 New York Times story in which he presciently warned that real estate prices could drop by 40 percent over the next generation. It took only three years for his predictions to be realized.

In his now-classic 2000 book, Irrational Exuberance, Shiller presented the case for the role played by human psychology in the volatility of many economic markets. A speculative financial market bubble, he wrote, occurs when price increases spur investor confidence and lead to increased expectations of future gains. The result is a positive feedback loop in which each increase in asset prices begets greater confidence, increased expectations, increased investment, and higher prices. These economic feedback loops involve some of the same basic dynamics as the Beauty Happens mechanism. Both sexual displays and asset prices can be driven by popularity alone, decoupled from extrinsic sources of value.

I asked Bob what he thought about the idea that there might be similarities between the intellectual frameworks of macroeconomics and evolutionary biology. He was particularly struck by how closely the arguments waged by efficient market theorists and adaptationist evolutionary biologists resembled each other. What he said made perfect sense to me:

To many economists, the mere existence of an asset at a given price indicates that its price must accurately reflect its value. That’s very similar to arguing that the existence of a given tree or bird in a certain environment demonstrates that it must have achieved an optimal solution to the challenge of survival because it has not yet been displaced by some other ecological competitor. Both use their views to interpret the world in a way that reinforces those views.

Such logic results in empirical intellectual disciplines that are more dedicated to confirming their own worldviews than to establishing an accurate understanding of the world.

For the title of their 2009 book about behavioral economics, Bob and his co-author, George Akerlof, revived the term “animal spirits,” which John Maynard Keynes coined to refer to the psychological motivations that influence people’s economic decisions. In the book, they document that research on “animal spirits” has been discouraged in economics precisely because these irrational influences are viewed as inherently unscientific and beneath consideration of a quantitative, scientific discipline. Ironically, I think there has been a parallel intellectual movement in evolutionary biology to banish consideration of the “animal spirits” of animals! Adaptive mate choice proposes that sexual desire always remains under strict control of the ultimately rational need for extrinsically better mates. In a curious anthropomorphic inversion of nature, animal passions are now seen as being more rational than our own.

A few weeks after my lunch with Bob, a team of economists published the results of a randomized, controlled experiment on the dynamics of Internet popularity. By randomly introducing thumbs-up or thumbs-down ratings into the comments section of stories on a major news website, the researchers demonstrated that popularity can be driven merely by popularity itself—what the authors called a positive herding effect—completely independent of variations in actual content quality. In other words, going viral on the web is often just a matter of stuff happening. When I next ran into Bob, I mentioned this new study as a vivid, experimental demonstration of the role of feedback loops in driving arbitrary popularity bubbles. “Are you going to write about that in your book?” he asked. “Because I was thinking about writing about that study in my book too!” Who would have imagined that an ornithologist and an economist would be in competition to report on the same research?

The Great Argus and the many other birds we will meet in these pages provide aesthetically extreme challenges to conventional, adaptive evolutionary theory. Neo-Wallacean adaptive mate choice may be more popular at the moment, but without Darwin’s broadly aesthetic perspective, we can never account for all the complexity, diversity, and evolutionary radiation of intersexual beauty in nature. Only the Beauty Happens hypothesis allows for a genuine engagement with the full, explosive diversity of sexual ornament.

I do not doubt, however, that meaningful, honest, and efficient signals of mate quality can evolve. There are circumstances in which mating preferences do indeed come under natural selection. Further, there may be circumstances in which signal honesty evolves to be so robust that it cannot be eroded away by the irrational exuberance of aesthetic desire. But we will never arrive at a genuine understanding of the diversity of nature by assuming that this is always true. We must use a nonadaptive null model to maintain the falsifiability of adaptive mate choice. Otherwise, it ceases to be science.

Although I am skeptical of adaptive mate choice, I do not claim that the “Emperor wears no clothes.” Actually, I believe that the “Emperor wears a loincloth.” In other words, I predict that the vast majority of intersexual signals can only be explained as the arbitrary evolutionary consequences of Beauty Happening, while the adaptive mate choice paradigm likely explains about the same proportion of the total “corpus” of intersexual signals in nature as is covered by that humble garment. How will we ever know if this prediction is correct? The only way for evolutionary biologists to proceed is to embrace the Beauty Happens mechanism as the null model of evolution by mate choice and see where the science leads.