CHAPTER 5

Make Way for Duck Sex

A few years ago my wife, Ann, and I attended a lovely dinner party in our New Haven neighborhood with four other couples. We dined by candlelight on a delicious meal at a table set with beautiful linens, crystal wineglasses, and hefty heirloom silverware, while a passel of young children ate in front of an animated cartoon in another room. Many of us were meeting for the first time, so we engaged in the usual polite introductions and chitchat.

A short way into our meal, the mother of a few of the spaghetti-eating children in the other room spoke to me from down the table. “Oh, you’re an ornithologist! You’re just the person I need to ask.” I expected to field another of the innumerable identification questions that arise from people’s personal encounters with birds, but her question proved to be much more thought provoking. “The other day I was reading Make Way for Ducklings to my kids.” I nodded in recognition of the classic story by Robert McCloskey, a book that had been read to me as a child and that I in turn had read to my three boys—so many times that I had nearly memorized it. “So, you know when the pair of Mallards settles down and builds their nest, and she lays her eggs? It seems that they’re just getting started with a nice family together, but then he just takes off! What’s with that?”

Before I could even inhale, from the other side of the table Ann gave me the anxious look we refer to in our house as the “hairy eyeball.” She murmured the verbal warning shot “Don’t go there!” Soon, all attention was on us, and everyone wanted to know exactly where it was I was not supposed to go. As if to warn all involved, Ann asked the curious mom, “You didn’t just ask my husband about duck sex, did you?”

From this casual inquiry into the family life of ducks, our conversation veered into territory I knew in far greater depth than anyone might have expected. Thanks to Dr. Patricia Brennan, who spent from 2005 to 2010 as a remarkably enterprising postdoc in my lab at Yale, my research in those years had taken an unexpected detour into the study of the sexual behavior and genital anatomy of waterfowl. So, just as my wife feared, discussion of the kinky qualities of duck sex came to dominate the conversation that evening.

Duck sex can be elaborately aesthetic or shockingly violent and deeply troubling, but it is a fascinating topic. It may not be the best subject for dinner table conversation among new acquaintances—perhaps that’s why we’ve never again been in the company of the woman who asked the question—but after all the disturbing details have been examined and understood, the story of duck sex actually concludes with a rather redeeming insight into the relationship between the sexes, the nature of desire, female sexual autonomy, and the evolution of beauty in the natural world.

The drama of duck sex brings to mind the ancient Greek myth of Leda and the Swan, in which Zeus took sexual possession of the lovely young Leda after assuming the physical form of a swan. This mythic scene has attracted the interest of artists ranging from the Greeks to Leonardo da Vinci to William Butler Yeats. Although often referred to as “the Rape of Leda,” it has usually been depicted with a note of sexual ambiguity, there being an element of mutual desire mixed in with the suddenness of the act. Perhaps the Greeks intuited that something about waterfowl sex is intriguing. If so, they were right, for the full evolutionary implications of the social complexity of duck sex are only beginning to be unpacked.

On a cloudy winter day in 1973, when I was twelve years old, I embarked on one of my earliest birding trips to the ocean. I stood on the banks of the Merrimack River in Newburyport, Massachusetts, just upstream from where it widens out into the bay. With the proceeds from a paper route and mowing lawns, I had just purchased my first spotting scope for watching distant birds, and I was excited to be using it to observe ducks, gulls, loons, and other waterbirds at this famous birding locality. It was a cold February day, with chunks of ice on the riverbanks and in some of the calmer eddies, but I was euphoric. I could see several dense flocks of ducks churning away against a strong current on the falling tide.

In my very first scan with the scope, I landed on a lifer!—a flock of a couple dozen Common Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula). The male ducks were crisp black on the back, snowy white on the sides, belly, and breast, and crowned with a shiny, iridescent green head. On each glittering green cheek was a large round white spot. As advertised, their eyes were brilliantly golden yellow. The females were drabber, with grayish sides and neck and a brown head, but they shared the same yellow eyes.

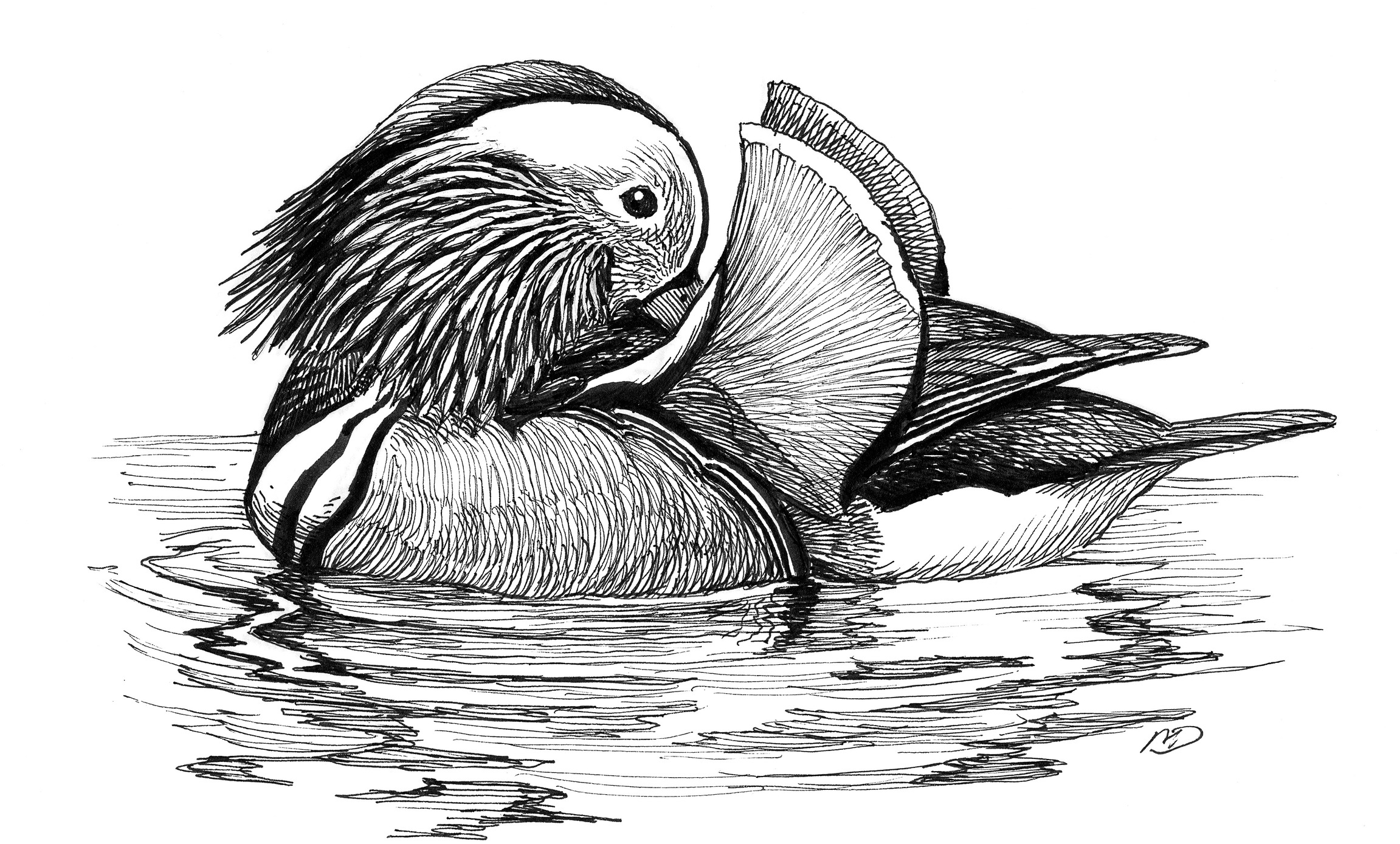

For some reason—a reason that I would not understand until years later—there were many more males in the flock than females. Among the two dozen or so birds, there were only five or six females. I was enjoying the scene, watching them as they dove underwater to feed and then popped back up to the surface, when suddenly a male thrust his head upward and then snapped it back to touch his rump—a display known as the head throw. With his head in this awkward position, he briefly opened his beak toward the sky, after which he brought his head back to its normal position with a slight side-to-side waggle. Soon, other males joined in, and the males in the flock were boiling over with bravado, jockeying for position around the females, and chasing each other. If I had been closer to the action that day, I would have heard the raspy two-note call the male Goldeneye makes during the head-throw display. The male Goldeneyes performed various other displays, too, which have been given suitably nautical names like the bowsprit and the masthead. The bowsprit involves cruising around with the head and beak pointed up and forward, while the masthead is performed with the head raised, then lowered and cast forward along the surface of the water. Despite the freezing weather, this gathering of Goldeneyes was engaged in courtship displays. They would continue wooing the females with these displays throughout the winter months, before returning to their nesting grounds on wooded lakes in northern Canada.

That memorable outing was my introduction into the complex social world of ducks. Across the entire waterfowl family, males engage in similarly showy courtship behavior. The displays vary among species, but they generally consist of a series of highly distinctive postures and gestures, each lasting only a few seconds. The males may repeat them over and over, but the basic elements are pretty simple, and because almost all duck displays take place on the water, they always involve a lot of churning, cruising, and splashing.

The head-throw display sequence of the male Common Goldeneye.

The display repertoires of some species of ducks are so outrageous that they can be quite comical. For example, the male Ruddy Duck (Oxyura jamaicensis) performs an especially impressive bubbling display. With his tail cocked straight up in the air, and his neck and breast swollen from air pumped into specialized pouches to either side of his esophagus, the male lowers his head rapidly and beats his blue bill against his rufous breast to make a low percussive pop sound. As he does so, his breast feathers create a frothy wake of bubbles on the surface of the water. He rapidly accelerates these chest-beating bill strokes in a crescendoing drumroll of ten or twelve pops that ends in a flatulent, groaning call that sounds like a breaking spring from a windup toy. The combination of feathers, postures, percussion, vocalization, and frothy bubbles makes for a very attention-getting performance.

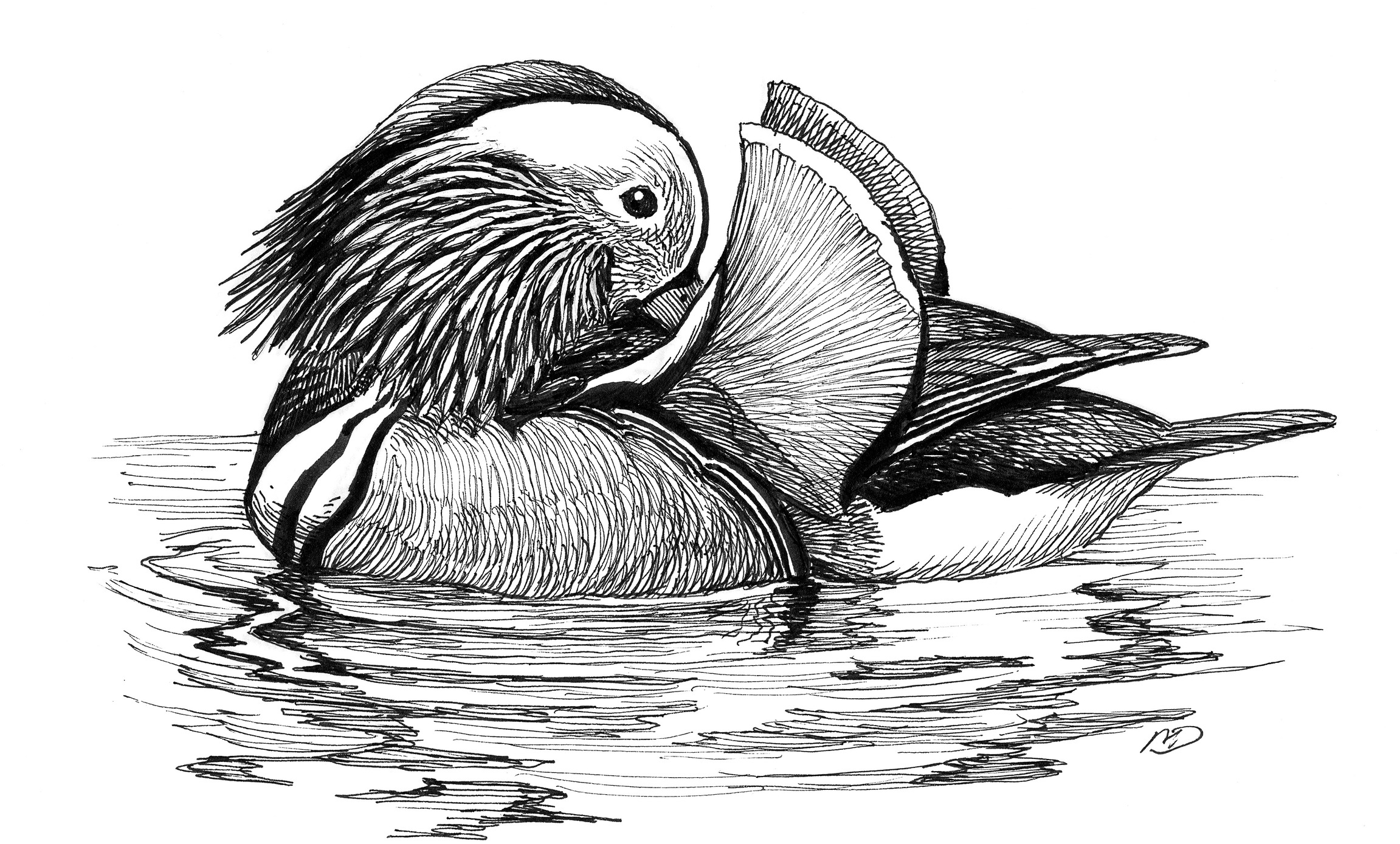

A particularly extreme example of the duck display genre is that of the lovely, diminutive male Mandarin Duck (Aix galericulata) of Eurasia. Many ducks perform sham preening displays in which they ostentatiously preen their back feathers. But the Mandarin Duck combines the sham preening with a drinking display, which looks not so much like a courtship display as a flamboyant demonstration of drinking incompetence characterized by copious dribbling. The Mandarin Duck’s sham preening is made more dramatic by the male’s uniquely shaped, brightly colored reddish-brown inner wing feathers, which stand up vertically above the surface of his back. The “purpose” of these unusual feathers only becomes evident during the male’s sham preening display when he reaches his head over his back (always on the side facing the female) and tucks his bright pink bill behind the upright planar feather, through which his eye is just visible to the female, as in a coy peekaboo game—or perhaps we should call it beak-a-boo.

I could go on and on. What all these rich and complex waterfowl courtship displays have in common is that they have evolved through female mate choice. Males go through all these antics in their quest to be selected as mates by the extremely selective females. On the basis of her observations of male display, the female duck makes her choice about which one she wants to pair up with. In many species, like the Common Goldeneye, females choose their mates on the wintering grounds, and after they form a pair, they remain together for the rest of the winter months. There’s no copulation during the winter months, because neither sex is ready. The annual cycle of sexual development in birds is a wild hormonal roller coaster, whose ups and downs are seasonally driven. Birds progress from completely asexual in the nonbreeding winter season to having gonads thousands of times larger only a few months later, in the spring, when it’s time to mate. As mating season approaches, the pair migrates together to their breeding grounds. Once there, the male will continue to display, as well as to defend the female from other males. After much displaying, the pair will copulate on the water. The female signals that she is ready for copulation with a distinctive solicitation display, in which she extends her neck forward, holds her body horizontal, and raises her tail.

The peekaboo sham preening display of the male Mandarin Duck.

Why are female ducks so picky about whom they mate with? Because they can be. Remember how the female Common Goldeneyes I saw were surrounded by males who greatly outnumbered them? In most duck species, the sex ratio is highly skewed toward males, so females have plenty of mates to choose from. Given such a wealth of options, female ducks have evolved lots of elaborate mating preferences for colorful male plumage, extravagant displays, and complex, funky acoustic stimuli. And because many ducks begin courtship months before they reach the breeding grounds in spring, female ducks have ample opportunity to put the males through their paces in order to make a decision.

Sounds great for the females. Unfortunately, there is a dark side to duck sex, too.

Although some waterfowl, like the Canada Goose, Tundra Swan, and Harlequin Duck, form enduring, monogamous pairs in which both parents help to defend an exclusive nesting territory and raise the young together, most duck species, like the Mallards my fellow dinner guest was querying me about, do not. What distinguishes them from the pair-bonding waterfowl is that they are not territorial. They nest in habitats where their food supply is so highly concentrated and the populations are so dense that an exclusive feeding territory cannot be defended by any pair. And because they are non-territorial, their sexual and social relationships are quite different from those of the territorial species.

In these non-territorial ducks, the primary functions of the male of the pair, once they arrive at the breeding ground, are to have sex with his mate and to protect her from the sexual depredations of other males during the ten to fifteen days she is laying her clutch of eggs. He has a strong evolutionary incentive to do so, of course, because he is protecting his own paternity. But once the eggs have been laid, there isn’t much for Papa Puddle Duck to do. The mother duck doesn’t need him, because the building of the nest and incubating of the eggs are done entirely by her. And their ducklings won’t need him either, because they’ll be able to feed themselves soon after they hatch. If males aren’t required to defend a territory against other members of their species, or to help with feeding the young, parental care in waterfowl consists mostly of trying to keep the ducklings from being eaten. This may actually be done better by one parent than by two, because more parental activity may only attract more predators, and the male’s bright plumage colors act as a predator magnet. So just as McCloskey wrote in Make Way for Ducklings, in many non-territorial waterfowl the male of the pair abandons the female as soon as she begins incubating the eggs. At that point, with his paternity guaranteed, the male duck can no longer benefit evolutionarily from defending her, and she probably cannot benefit from his remaining with her. Which answers my dining companion’s question: “What’s with that?”

But now comes the shocking part about duck sex, the part that wasn’t included in McCloskey’s otherwise scientifically accurate children’s story about puddle duck family life, the part that few would even think to ask about. McCloskey said nothing about the challenges the father duck might have faced in protecting his mate, or what might happen to her if his defenses were unsuccessful. Or where the male duck goes after he leaves. And this is where things can get very scary indeed in the world of the female duck.

Whenever there are a lot of ducks present in relatively small spaces, like the high-density ecologies of non-territorial puddle ducks, there are lots of opportunities for social interactions. For males, these social opportunities are also sexual opportunities. Because of the excess males in the population, many males end up unpaired. These unpaired males now have two reproductive options: they can wait another year and hope they have better luck; or they can try to coerce and force themselves on unwilling females. Thus, forced copulations are an alternative male reproductive strategy. Males whose mates have already begun to incubate may also pursue forced copulations when they leave their mates, which creates even darker implications to the Mallard drake’s casual departure in Make Way for Ducklings.

“Forced copulations” is the term that ornithologists and evolutionary biologists now use to refer to rape among birds and other animals. The use of the word “rape” was routine in animal biology for over a century, but it was largely abandoned in the 1970s in response to multiple avenues of feminist critique. In particular, in Against Our Will, Susan Brownmiller built a powerful and effective argument that rape, and the threat of rape, in human societies functions as a mechanism for social and political oppression of women. Human rape is an act with such great symbolic and social impact that the term didn’t seem appropriate in the context of nonhuman animals. As the ornithologist Patty Gowaty has written, “Because of the important differences between rape and forced copulations, those of us who study animal behavior agreed years ago to refer to ‘forced copulation’ in non-human animals, and to reserve the term ‘rape’ for humans.”

I understand and agree completely with those concerns, but I think, unfortunately, that the shift to the term “forced copulation” in biology has contributed to a desensitization to the social and evolutionary impact of sexual violence in animal behavior. It has obfuscated the fact that forced copulation is a form of coercive sexual violence against the interests of many female animals as well, and it may have stunted our understanding of the evolutionary dynamics of sexual violence. (In chapter 10, I will further explore how this missed intellectual opportunity has held back our understanding of the impact of sexual violence in human evolution.)

Although I do not suggest that we return to the wholesale use of the word “rape” in animal biology, I think that the phrase “forced copulation” does an intellectual disservice to our understanding of sexual violence in nonhuman animals. Certainly, in the case of female ducks, it is scientifically critical to recognize that sexual coercion and violence are very much against their wills too.

Forced copulations are pervasively common in many species of ducks, which might suggest that there’s something routine and ordinary about them, but they are also violent, ugly, dangerous, and even deadly. Female ducks are conspicuous in resisting them and will attempt to fly or swim away from their attackers; if they do not manage to escape, they mount vigorous struggles to try to repel their attackers. This can be extraordinarily difficult to do, because in many duck species forced copulation is often socially organized. Groups of males travel together and attack a single female in a form of gang rape. By attacking her in concert, males increase the chance that one of them will be able to overcome her resistance, and thwart her mate’s attempts to defend her, than if they acted alone.

The cost to females of forced copulations is very high. Females are often injured, and not infrequently killed, in the process. So, why do female ducks fight back so vigorously? Female ducks absorb greater direct harm to their physical well-being by resisting forced copulations than if they acquiesced, so the intensity of their resistance seems difficult to explain from an evolutionary perspective. Nothing is more threatening to the ability to pass on one’s genes than death, so why risk death by struggling?

This question delivers us to the crux of the complex interaction between the female acting on her sexual desire for beauty and the male using sexual violence to subvert her ability to choose her own mate. What is at stake in these attempts at forced fertilization is more than just the direct cost to a female’s health and well-being; forced fertilizations will also create indirect, genetic costs to the female that may be even more important to the female. Why? Because females that succeed in mating with the males they prefer will likely have offspring that inherit the display traits that they, and other females also, prefer. These females will have the benefit of greater numbers of descendants through their sexually attractive offspring. This is the indirect, genetic benefit of mate choice that drives so much of aesthetic coevolution. Females that are forcibly fertilized, however, will have offspring that are sired by males that have random display traits, or traits that have been specifically rejected because they have failed to meet female aesthetic standards. Either way, the resulting male offspring will be less likely to inherit genes for the preferred male ornamental traits, and they will therefore be less sexually attractive to other females and less likely to obtain mates, which will result in fewer grandchildren for that female. This is the indirect, genetic cost of male sexual violence.

At the heart of the complex breeding biology of ducks is sexual conflict between males and females over who is going to determine the parentage of the offspring. Will it be females through mate choice based on the coevolved beauty of male plumage, song, and display? Or coercive males through violent forced copulation? In 1979, Geoffrey Parker defined sexual conflict as a conflict between the evolutionary interests of individuals of different sexes in the context of reproduction. Sexual conflict can occur over many aspects of reproduction, including who gets to mate, how often sex occurs, and the division of parental care investment and responsibilities. One of these sources of conflict is critical to the evolution of sexual beauty: the conflict over who will control fertilization, the purveyors of the sperm or the curators of the eggs.

Duck sex provides a premier example of sexual conflict over fertilization and allows us to investigate how Darwin’s proposed “taste for the beautiful” creates the opportunity for the further evolution of sexual autonomy. A key insight is that both fundamental mechanisms of sexual selection in waterfowl—mate choice based on female aesthetic preferences for male displays, and male-male competition for control over fertilization—are occurring and in evolutionary opposition to each other.

This observation is actually quite subversive. As we’ve seen, ever since Darwin’s publication of The Descent of Man, the mainstream, adaptationist, Wallacean view has considered all forms of sexual selection as forms of natural selection. Whether it’s elephant seals or birds of paradise, this view holds that only the objectively “best” males will succeed at mating. But what happens when female mate choice and male-male competition operate simultaneously, and they are clearly running in different directions, as they do in waterfowl? The winners of these two distinct competitions cannot all be the “best.” If the most sexually aggressive males are actually the best, why don’t females prefer them? Clearly, the winners in mate choice and male-male competition cannot all be the same.

Rather, sexual violence is a selfish male evolutionary strategy that is at odds with the evolutionary interests of its female victims and possibly with the evolutionary interests of the entire species. By maiming and killing females, such violence lowers the population size of the species. And by further skewing the sex ratios, these violent deaths make sexual conflict even worse, because there will be more males losing out in the mate choice competition who will therefore be motivated to pursue this counterproductive strategy. Thus, sexual conflict in ducks demonstrates yet again Darwin’s insight that sexual selection is not equivalent to natural selection.

One reason why duck sex is so exceptional is that unlike 97 percent of all bird species ducks still have a penis. The bird penis is homologous with the penis of mammals and other reptiles, but somewhere along the way the ancestor of most bird species lost his penis (more on that later in the chapter). Ducks and the other bird species that still have penises—including the nonflying birds the ostrich, emu, cassowary, kiwi, and rhea, and their close relatives, the flying tinamous—belong to the oldest extant branches in the avian Tree of Life. Among all the birds with penises, the ducks are the best endowed, in terms of the ratio of penis size to body size. In fact, one duck species is the best endowed of all vertebrate animals. In a 2001 paper in the prestigious journal Nature, the ornithologist Kevin McCracken and colleagues described the penis of the diminutive Argentine Lake Duck (Oxyura vittata). A duck that was itself only about twelve inches long and a little over a pound in weight had a forty-two-centimeter penis (about sixteen inches). The Nature paper, now cited in the Guinness World Records, was titled “Are Ducks Impressed by Drakes’ Display?” McCracken hypothesized that female ducks may select their mates based on penis size. After all, what other possible explanation could there be for such an extravagant genital endowment?

However, we now know that penis size is not important in mate choice in most ducks because, believe it or not, the seasonal nature of the reproductive cycle means that the superlong duck penis is almost nonexistent during courting season, when the females choose their mates. The penis regrows every year as mating season approaches, but once mating season is over, it begins to shrink and regress, until it’s reduced to a small rudiment less than a tenth of its full-grown size.

The record-setting 42 cm penis of a male Argentine Lake Duck. Photo by Kevin McCracken.

Alternatively, McCracken also hypothesized that the male somehow uses his superlong penis to remove the sperm of other competing males from the female’s reproductive tract. Proving once again that each scientific discovery merely opens up other unsolved mysteries, the paper concluded with the inquiry “How much of his penis does the drake actually insert, and does the anatomy of the females’ oviducts [vaginas] make them unusually difficult to inseminate?”

In 2005, this question resonated with the interests of my new colleague Patricia Brennan. Brennan is Colombian but has lived in the United States for more than fifteen years. She is vivacious, enthusiastic, and scientifically unstoppable. She is not at all timid about working on, or talking about, avian sex. With two young children and a bit of gray hair, she still looks like the aerobics instructor she was during graduate school at Cornell. She is also a mean salsa dancer, which is to say still una Colombiana. Her Ph.D. was on the dinosaur-like, male nest care breeding system of the tinamous (Tinamidae). In the tropical rain forests of Costa Rica, Brennan came to know these extremely shy, chicken-like birds better than nearly anyone alive.

Once, when observing tinamous mating, Patty was shocked to see a fleshy spiral dangling down from the male’s cloaca. The cloaca (a word that memorably derives from the Latin for “sewer”) is the anatomical chamber inside the avian anus, which is a kind of one-stop business rear end that receives the outflow of the digestive, urinary, and reproductive tracts. In birds without penises, insemination takes place with a “cloacal kiss”—a poetical term for a chaste juxtaposition of orifices in which the male and female anuses come into contact, the male releases his sperm, and the female takes it up. The male does not enter the female, because he doesn’t have anything that would allow him to. The tinamou penis had been described by Victorian anatomists who had performed dissections on natural history museum specimens, but these anatomical monographs were not inspiring enough to keep the topic alive scientifically, and the existence of the tinamou’s penis had been almost completely ignored for more than a century. So when Brennan spotted the extrusion from the cloaca of the postcoital male tinamou, she was stunned. Her sighting was probably the first-ever observation of the tinamou penis in action.

When Patty first arrived in my lab in 2005, she was interested in continuing her studies of the tinamous, focusing on the anatomy and function of their penises. But tinamous are eminently edible, and they are heavily hunted throughout their range, which is why they are among the shiest of all the birds in the world, and therefore very hard to study in the wild. Whereas ducks also have penises and are comparatively easy to work with. So, Patty thought that ducks might provide an easier route to study the evolution of genital anatomy and function in birds.

This interest ultimately led her to a duck farm in the Central Valley of California in 2009. Although a duck farm is not an obvious place to pursue new frontiers of evolutionary science, the farm Brennan went to had some very special ducks. These drakes were trained to ejaculate semen into tiny glass bottles. This was done not to satisfy some perverse interest in duck sex but because the duck farmers wanted to create offspring that are a hybrid of male Muscovy Ducks (Cairina moschata) and female Pekin ducks (a captive breed of Mallard). In captivity, such hybrids show extraordinary vigor and put on weight rapidly—two qualities that are very attractive to duck farmers. But the Muscovy and Pekin ducks do not like each other, and if they are left to their own devices in a common pen, they will not mate at high enough rates to produce a commercially viable number of offspring. Modern agriculture’s answer to this problem is artificial insemination, which requires some way of collecting the sperm. Hence the use of the little glass bottles.

All of which explains why one day the Latino workers who collected the sperm and performed the artificial inseminations at this farm were confronted with a lovely, well-educated, wise, and wisecracking Latina toting a high-speed video camera. As the videos showed, male Muscovy ducks will perform on demand—despite the little glass bottles, the scrutiny of the camera, and the glare of the lights.

The basic artificial insemination procedure goes like this: Male and female Muscovys are kept in separate pens to increase their sexual motivation. When it’s time for the sperm collection to occur, the pair of ducks is placed in a narrow cage with their rear ends facing out of one open side. The male rapidly mounts the female and begins to tread on her back. The female becomes readily sexually receptive, as indicated by her reclining precopulatory posture: her neck extended forward, head lowered, rear end raised with the cloaca exposed, dilated, and secreting volumes of mucus. Soon, the male begins to lower himself toward the female’s proffered rear. And then it happens.

Normally, the erection of the drake would take place into the female reproductive tract. During sperm collection, however, the farmworker prevents the male from actually entering the female and places what looks like a small glass milk bottle over the male’s cloaca at just the right moment. The drake’s penis then erects and ejaculates into the bottle. As in a discreet sperm bank, the sample is then passed through a little window into the hand of another worker who prepares it for the Pekin females who are waiting in the room next door. For Brennan’s research observations, the farmers still prevented the male from entering the female but allowed him to erect and ejaculate into the air, or into the special glass contraptions that Brennan brought along on her next trip to the duck farm (more about those later).

Obviously, despite their ancient homology, the duck penis and the human penis are very different from each other. Like other reptiles, the duck penis is not external, but is stored, folded up, outside in, within the cloaca. It only emerges from the cloaca during copulation. Another difference is that unlike the erections of other reptiles, and of mammals, too, duck erections are powered not by the blood-fueled vascular system but by the lymphatic system. Inside his body on either side of the cloaca, the male duck has two muscular sacs, called lymphatic bulbs. When these contract, lymph squirts into the central hollow space within the penis, causing the penis to erect, rapidly unfurling out of the male’s cloaca. It is difficult to envision, but the process generally resembles a cross between using your arm to evert a sweater sleeve that is inside out and unfurling the soft, motorized roof of a convertible sports car with a hydraulic drive—but much, much faster! The first part of the penis to be exposed is the base, and the rest unfolds in a wave toward the tip, with sperm traveling along an external groove on the penis from base to tip.

For ducks, the erection of the penis and its entry into the vagina are the same event. The duck penis does not become stiff and then enter the female, as in mammals and other reptiles. Rather, the penis is erected, or actively everted, into the female reproductive tract, and it remains flexible throughout the entire process. Furthermore, the duck penis is not straight, but spirals counterclockwise from its base to its tip. Over its twenty-centimeter length, the Muscovy Duck penis completes six to ten full twists.

The penises of ducks and other reptiles also lack an enclosed urethra, or tube, for the flow of semen. Instead, the duck penis has a sperm-carrying groove, called the sulcus, to transport semen. The sulcus runs along the entire length of the duck penis, rather like the seam in a shirtsleeve. But because the penis is coiled, the sulcus spirals counterclockwise as well. Those same Victorian anatomists who had described avian penises derided the sulcus as functionally ineffective—like a leaky, dribbling pipe. But they had clearly never watched the duck penis in action, and their armchair conjectures could not have been more wrong. As the high-speed videos of flying duck sperm would show, the avian sulcus may be a mere topological fold, but it works as well as any mammalian urethra.

Like a selection of sex toys from a vending machine in a strange alien bar (think perhaps of an X-rated Far Side cartoon by Gary Larson), duck penises come in ribbed, ridged, and even toothy varieties. These surface features point backward toward the base of the penis, and as the penis unfolds, they are rapidly deployed into the walls of the female reproductive tract to secure whatever inward progress the unfurling penis has made, like the pitons a mountain climber uses to maintain progress up a forbidding cliff face. Oh, and did I mention the duck penis’s spiral twist? I did? Okay, well, there are so many odd things about a duck penis that it’s hard to keep them all straight.

Although Brennan was well prepared by years of previous research on duck anatomy, even she was stunned by the duck penis in action. To be blunt, duck erections are “explosive,” the very word we used in the paper we eventually published about our findings in Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: “Eversion of the 20 cm muscovy duck penis is explosive, taking an average of 0.36 s, and achieving a maximum velocity of 1.6 ms-1.”

That’s nearly eight inches unfurled at three and a half miles an hour. In about a third of a second, the entire event is over, the male ejaculates, the penis begins to deflate, and the drake starts retracting it into his cloaca with a series of muscular contractions (color plate 16). Brennan’s data show that it takes an average of two minutes for a male to complete the process of gathering his penis back inside his cloaca, or 190 times longer than it takes to erect it in the first place. Brennan was able to make these observations about speed because during her first trip to the California duck farm, she had filmed the high-speed duck erections in the open air to document the process of an unimpeded duck penile erection. This gave us the first measures of the velocity of erection and the first observations of the efficacy of the sulcus—the sperm-carrying groove that runs along the length of the penis.

After ejaculation and retraction, the farmers know that it will then be hours before the male will be able to perform sexually again—perhaps because that’s how long it takes for a sufficient quantity of lymph to build up in the male’s lymphatic bulbs to fuel another explosive erection. Whatever the reason, it takes a few hours for a drake to get his groove back.

When our duck-farm research was published, what was everyday knowledge to the farm workers turned out to be both scientifically notable and culturally irresistible. The videos themselves attracted tens of thousands of YouTube viewers in just the first few days—a veritable explosion of interest, shall we say.

Which brings us back to McCracken’s question: How does the explosive, spiraling, ribbed, or even toothy duck erection function within the female duck? Why do some males evolve a forty-two-centimeter penis to fertilize a thirty-centimeter-long female duck? To find out, Brennan dissected the reproductive tracts of female barnyard ducks. What she found was, at first, wildly confusing. According to the textbooks, the avian vagina is a simple thin-walled tube that runs from the single ovary to the cloaca. But the textbook illustration didn’t match up at all with what Brennan saw in the female duck’s reproductive tract. The duck vaginas she examined had thickened, convoluted walls that were wrapped in a mass of fibrous connective tissue. To Brennan, they seemed at first like a complete and confusing mess. Then, surprisingly, in other specimens, she saw vaginas that were simple, thin tubes, just like those in the textbooks. Eventually, Brennan discovered that the simple tube specimens were from females outside the breeding season and the more complicated structures were found in females who were in breeding season. Turns out that the reproductive anatomy of the female duck follows the same seasonal rhythms as that of the male duck, with both of them redeveloping every year at breeding time.

Once Brennan was able to examine the vaginal anatomies of a number of breeding ducks, what she found instead of simple tubes were vaginas that had a series of dead-end side pockets, or cul-de-sacs, located near the cloaca at the bottom of the reproductive tract. Further up the reproductive tract, she saw a series of twists and turns in the vaginal tube. Interestingly enough, these twists were clockwise spirals, in the opposite direction of the counterclockwise-spiraling duck penis. Broadening the sample to include a comparative analysis of fourteen waterfowl species such as puddle ducks, diving ducks, mergansers, geese, swans, and “stiff-tailed” ducks, like the Ruddy, Brennan showed that the longer and twistier the penis, the more complex the vagina, with more dead-end pockets and upstream twists—and vice versa: the shorter the penis, the simpler the vagina.

But what was the cause of all this anatomical variation? The key insight was that there was a correlation between the more highly elaborated genital structures and the social and sexual lives of the species who possessed them. In monogamous, territorial waterfowl like swans, Canada Goose, and Harlequin Duck, males have a very small penis (about one centimeter) without any surface features, and females have simple vaginas without cul-de-sacs or spirals. But in non-territorial species, which frequently engage in forced copulations, like the Muscovy Duck, Pintail, Ruddy Duck, and, yes, even the Mallards in Make Way for Ducklings, males have evolved longer, intricately armed penises, and females have evolved increasingly complex vaginal structures. A comparative analysis of penis and vaginal morphology showed that these two features—the longer and more elaborately structured penises and the more complex and convoluted vaginas—had clearly coevolved with each other. But why?

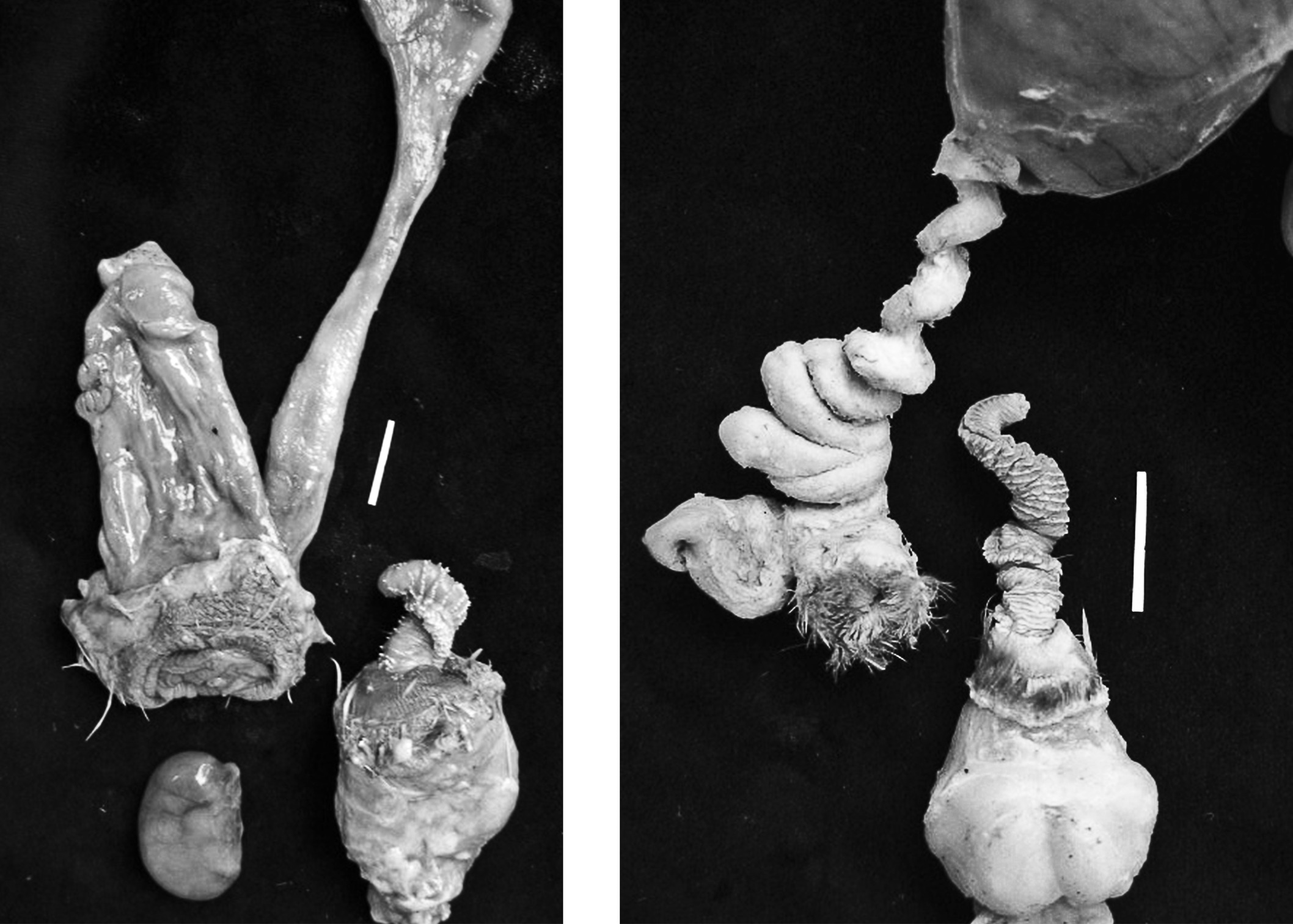

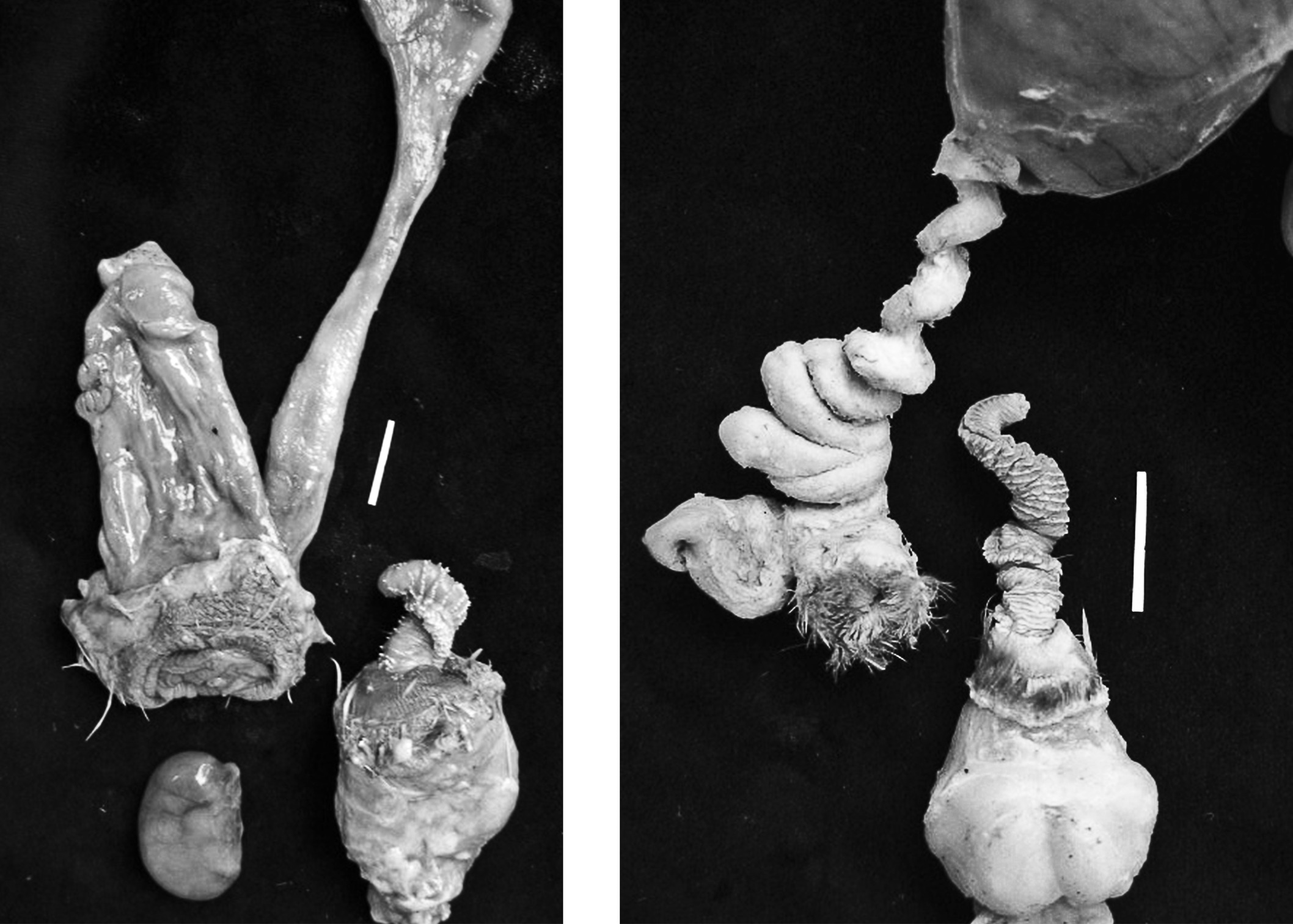

Coevolution of male and female genital morphology in waterfowl. (Left) The male Harlequin Duck has a very small, centimeter-long penis, and the female has a simple, straight vagina with no elaborations. (Right) The male Mallard has a long, corkscrew-shaped penis with hard ribs on its surface, and the female Mallard has coevolved a convoluted vagina with multiple dead-end cul-de-sacs, and several clockwise spirals. Photos by Patricia Brennan.

We hypothesized that the coevolutionary elaboration of the duck penises and vaginas was the product of the sexual conflict between males and females over who is going to determine the paternity of the offspring. In cases like waterfowl, sexual conflict can create an ever-escalating war between the sexes, which is called sexually antagonistic coevolution. This process results in a kind of arms race between males and females, in which each sex evolves successive behavioral, morphological, or even biochemical mechanisms to overcome the evolved efforts by the other sex to assert control or freedom of choice over reproduction. That is, each evolutionary advance by one sex selects for a compensating counterstrategy by the other.

Male ducks had evolved penises that would enable them to force their way into an unwilling female’s vagina, and the females in turn had evolved a new way—an anatomical mechanism—to counter the action of the explosive corkscrew erections of male ducks and prevent the males from fertilizing their eggs by force. Remember the duck penis is never stiff but unfurls flexibly in a counterclockwise spiral into the female’s reproductive tract. It seemed to us that the cul-de-sac side pockets of the vagina, and its clockwise corkscrewed shape, could be blocking the drake’s penis from progressing up the female reproductive tract during forced copulations. If the evolutionary advances in the female vaginal anatomy succeeded in foiling coercive fertilization, then males would evolve to counter female defenses with bigger, better-armed penises, and the females would in turn evolve ever more complex evasive anatomical structures, and so on and so forth.

The selection mechanisms at work in this dynamic coevolutionary process are complex. There is the sexual selection by mate choice that produces coevolution between male display traits and female preferences. In addition, male-male competition—another kind of sexual selection—is acting in the evolution of the coercive male behavior and in the evolution of the longer and more aggressively armed penis that allows males to succeed at fertilizing the females by force. Further, in response to the indirect, genetic benefit of autonomous mate choice (also a kind of sexual selection), female behavioral and anatomical resistance mechanisms evolve. Any genetic mutations that contribute to behaviors or vaginal morphologies that help females avoid forced fertilizations will evolve because those mutations will help females evade the indirect, genetic costs of sexual violence—that is, having unattractive sons that other females will not prefer.

On the face of it, this is a pretty depressing picture of duck social relations. It seems much more suitable for an apocalyptic dystopian sci-fi novel than a Caldecott Medal–winning children’s bedtime story. The story, however, is not all depressing. There have been both escalations and reductions in this arms race in different lineages of ducks. Though some duck groups have evolved ever-longer and more elaborately armed penises and more complex vaginas, other lineages of ducks have essentially called off the arms race and evolved smaller penises and simpler vaginas. These reductions seem to be the result of external ecological factors that lower the density of breeding individuals, favor exclusive territoriality, and eliminate the social opportunity for male sexual coercion. In the absence of sexual conflict, both sexes seem to evolve away from these complex structures.

We wanted to test our hypothesis that female vaginal complexity functions in preventing forced fertilization. That required investigating whether there was something about the cul-de-sacs and spiral twists of the duck vagina that is specifically, mechanically designed to thwart the advance of the duck penis.

How could we test this hypothesis? It is impossible to get internal images of ducks during their sex act. Even if one could arrange for a male duck to forcibly copulate with a female in an MRI machine with the capacity to show a clear contrast between male and female tissues (and one definitely cannot!), it would be impossible to complete the imaging in the few tenths of a second during which penile erection is maximized and ejaculation takes place. Testing this hypothesis about sexually antagonistic evolution would take some creative thought.

Patty is nothing if not creative, however, and to test our hypothesis, she came up with the idea of creating four glass tubes that would help us analyze the interplay between the male and the female reproductive equipment. Two of the tubes would be designed not to challenge the progress of the duck penis in the vaginal tract. One would be straight; the other would be coiled counterclockwise to match the spiral of the duck penis itself. The other two tubes would be designed to act like a steeplechase obstacle course for the avian penis, mimicking the shape of the female reproductive tract in breeding season. One would be a tube with a hairpin turn similar to the female cul-de-sacs near the cloaca, and the second a tube with a clockwise coil like the upper reaches of the duck vagina. The diameters of all the tubes were to be the same; they would differ only in the shape of the interior space. We hypothesized that the duck penis would proceed without problems through the straight and counterclockwise spiral tubes. Conversely, we hypothesized that the tubes with the female-like hairpin turn and the clockwise spirals could frustrate erection and prevent complete entry.

Although glass tubes are nothing like the real thing, they have the advantage of providing a standard rigidity and uniformly smooth surface that would control for all mechanical factors other than the shape of the tube, which was the critical element of the hypothesis we wanted to test. The glass tubes would be unnatural but objective and fair. Plus, glass is clear, so we could observe and record on video the progress of the erecting duck penis down the tube.

To find someone to make the glass tubes, Patty and I went to talk to Daryl Smith at the Yale University Department of Chemistry Scientific Glassblowing Laboratory. The motto over the door read, “If not for glass, science would be blind.” The display cases in the hallway leading up to the shop were filled with complex glass apparatuses with elaborate condensing coils, leading to flasks and bulbs leading to tubes with charcoal filters, and so on. Business was booming. Waiting outside the door was a line of students, each holding drawings of new designs they wanted to be made for their research, proof if any were needed that this classic art form is still a critical part of the science of chemistry. When our turn came to talk to Smith, we gave him a short introduction to the reproductive biology of ducks, to explain why we wanted him to make artificial duck vaginas in various shapes. We discussed the possible designs. Once we had decided on the final specifications, I asked Smith, “So, is this the weirdest request you ever had?” “Well,” he responded, “I’ve been asked to make artificial vaginas before, but never for ducks!” We didn’t inquire further about this previous request.

Brennan returned to the duck farm with new glass tubes in the male-friendly straight and counterclockwise spiral shapes and in the female-like hairpin and clockwise spiral shapes. When she placed the straight and the counterclockwise spiral glass tubes over the male Muscovy Duck cloacae, the penises succeeded at erecting completely 80 percent of the time, and they unfurled at the same velocity as a duck erection into open air. The few cases that did not erect completely only failed to unfurl at the very tip of the penis. In contrast, when faced with the hairpin and clockwise spiraled tubes, the Muscovy Duck penises failed to erect 80 percent of the time. In each of these cases, the erection failure was complete. The penis became bottled up in the hairpin turn or in the first bend or two of the spirals and could not advance further. Sometimes, the penis proceeded to unfurl backward toward the opening of the glass vagina. These observations confirmed that the clockwise spirals of the duck vagina literally function as an anti-screw device.

To those who may feel concern about the feelings of the male ducks, they ejaculated just fine despite any and all mechanical challenges and seemed not to mind in the slightest. Turns out that because sperm travels down the sulcus, a duck penis can ejaculate regardless of how extensively it is erected. This observation might suggest that all the female’s defensive structures are for naught. From the female perspective, however, the earlier the progress of the penis into the vagina can be impeded before ejaculation, the farther away from the ova the sperm will be when they are deposited, and the greater her chance of expelling the unwanted sperm with muscular contractions and preventing sexually coercive fertilizations.

The data from Brennan’s glass tube experiments supported our hypothesis that the convoluted vaginal morphologies found in some duck species function to repel the explosively flexible duck penis during forced copulations. Further supporting these conclusions are real-life genetic data showing that these novel anatomical features are actually incredibly effective at preventing fertilization by force. By doing genetic paternity analyses, biologists can determine whether a female duck’s offspring were fathered by her chosen male social partner or by other, extra-pair males. In several duck species, including Mallards, in which the forced copulations are a stunning 40 percent of the total copulations, only 2–5 percent of the young in the nest are sired by a male who is not the chosen partner of the female. Thus, the overwhelming number of forced copulations are unsuccessful. As a consequence of their elaborate vaginal morphologies, female ducks have indeed succeeded in maintaining freedom of choice for 95 percent of paternity despite persistent sexual violence.

But how is it, then, that the mate the female chooses can manage to overcome the twists and whorls of her defensive anatomy? How does voluntary sex differ from forced? We do not have any direct observations of the inner workings—again, MRI technology would need to take a huge leap forward and arrive in the barnyard to deliver such data. But, as mentioned above, Patty’s duck-farm observations revealed that when female Muscovys were actively soliciting copulations, they assumed the conspicuously horizontal precopulatory display posture, dilated the cloacal muscles, and released copious amounts of lubricating mucus. It seems clear that females can make the reproductive tract a fully functioning and welcoming place when they want to.

To return once again to McCracken’s question—what are the ridiculously long penises of these ducks doing inside the female’s body? The answer turns out to be, “It depends.” If the copulation is solicited, then clearly the female is in for the full ride. These penile structures can easily penetrate to the upper reaches of her reproductive tract if only momentarily. However, if the copulation is resisted by the female, then the penis’s length and surface features are designed, evolutionarily speaking, to try to overcome the barriers imposed by female vaginal complexity. In the text above, I didn’t use the metaphor of the forbidding cliff face lightly. It’s clear that the ridges and hooks on the penis have evolved precisely for the purpose of helping it to claw its way through the various structures within the duck’s vagina that are designed to keep it out. However, by being overwhelmingly successful at bottling up the penis during forced intromission, and preventing the vast majority of attempts at forced fertilizations, female ducks have managed to maintain the advantage in this sexual arms race. Even in the face of persistent sexual violence, female ducks have been able to assert and advance their sexual autonomy—their individual freedom to control paternity through their own mate choices.

This is a dark evolutionary tale with an amazing and profoundly redemptive outcome. What we learn from our investigations into duck sex is that despite the ubiquity of sexual violence in these breeding systems, female mate choice continues to predominate. Consequently, male plumages, songs, and displays continue to evolve. Beauty continues to thrive, even in the face of pervasive, violent attempts to subvert the freedom of mate choice that creates it. However, female sexual autonomy is not a form of female power over males. It is merely a mechanism for the assurance of freedom of mate choice. Female ducks do not exert sexual control over males, and they can always be turned down by the mates they prefer. Females do not, indeed cannot, evolve to assert power over others in response to sexual violence. Rather, females can only evolve to assert their own freedom of choice.

In this way, the concept of a sexually antagonistic coevolutionary arms race is really misleading because the “war of the sexes” is highly asymmetrical. Males evolve weapons of control, while females are merely coevolving defenses that create opportunity for choice. It’s not a fair fight, because only males are really at war. However, as ducks show, female sexual autonomy can still win.

In March 2013, shortly after Barack Obama was inaugurated for his second term, negotiations between congressional Republicans and the White House over the U.S. federal budget broke down once again, and Republicans turned their attention to one of their favorite subjects: wasteful government spending. And that’s how the research that Patty Brennan and I had done on sexual conflict and the evolution of duck genital anatomy became the focus of a mini-scandal about government excess, which propelled the topic of duck sex into the maelstrom of the political news cycle, where it was catchily dubbed Duckpenisgate by Mother Jones.

Our duck genital evolution research had been funded by a 2009 grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF), with money coming from the aptly named “stimulus” package—the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). For purposes of transparency, ARRA established an independent website, Recovery.gov, which allowed citizens to “track the money” and see where their stimulus tax dollars were going. This is how, as I imagine it, some enterprising intern at Cybercast News Service (CNS), a conservative news website, came across our grant just a few months before it was due to expire. When a CNS news story describing our grant was posted on its blog, a conservative Twitter storm of outrage ensued. For example, the columnist Michelle Malkin tweeted, “Pass me the mind bleach. Blech.” (Of course, why would you retweet a story you were supposedly so eager to forget?) The CNS story was quickly followed up on by Fox News, and the story went into heavy rotation for the week.

The Fox News anchorwoman Shannon Bream introduced a weeklong series of investigations into federal government waste with the following question:

Did you know that $385,000 of your tax dollars were being spent to study duck…anatomy? You heard that correctly—$385,000 of your money to study the private parts of ducks. It’s part of President Obama’s stimulus plan, and it’s just one example of the kind of spending decisions that have added up to massive debt and deficits.

The three-minute piece that followed was a tour de force of the tired genre of big-government lament. I never imagined it could be possible to combine quotations from Ronald Reagan (“Government is not the solution to our problems. Government is the problem!”), images of the Twin Towers burning, Barack Obama’s teleprompter, and America’s housing foreclosure and banking crises into an attack on our animal genital coevolution research program, but Fox News managed to accomplish just that. Never one to shy away from any antigovernment cause, Sean Hannity discussed the validity of federal funding of a Yale University study on duck genital evolution with Tucker Carlson and Dennis Kucinich later in the week in a segment titled “D.C. Wasteland.”

Our duck penis research did have its strong defenders in the media, among them Chris Hayes on MSNBC, the science writer Carl Zimmer, Mother Jones, the Daily Beast, Time, and PolitiFact. After Patricia Brennan wrote an awesome defense of basic science research and funding for Slate.com, the storm appeared to be over.

Eight months later, however, when Senator Tom Coburn of Oklahoma published his Wastebook for 2013 and included our $385,000 grant as number 78 among the top 100 examples of federal government waste, the irresistible story of Duckpenisgate roared back to life. The New York Post headline read, “Government’s Wasteful Spending Includes $385G Duck Penis Study.”

Out of the $30 billion of waste reported in Wastebook, the Post headline focused on the 0.001 percent that went to our study. Somehow, the combination of money, sex, and power—your tax money, duck sex, and Yale’s Ivy League prestige—made the story irresistible. And so it went, as the right-wing news outlets sought new ways to inspire the outrage that in an earlier era was reliably engendered by Ronald Reagan’s Cadillac-driving “Welfare Queen” and the Defense Department’s $700 toilet seats.

When repeddling this old story of government profligacy, news programs inevitably mentioned our research with a veneer of sexual titillation. So, when Sean Hannity sarcastically asked Tucker Carlson on Fox News, “Don’t we really need to know about duck genitalia, Tucker Carlson?” his question belied the genuine human fascination with the topic. Like all the other attackers, he ignored the fact that we actually do have a tremendous amount to learn from the study of duck sex. There are important evolutionary findings, and perhaps even some of immediate practical value. If the pharmaceutical industry thought that Viagra was a big deal, just wait until duck developmental biologists unlock the secrets of the stem cells that allow the duck penis to regenerate itself every spring and to get bigger each year (which I think I might have forgotten to mention)!

Furthermore, our research has discovered that what the 2012 Missouri Republican Senate candidate Todd Akin said about rape in humans—that “the female body has ways to try to shut that whole thing down”—is actually true of ducks, but the reason it is true tells us something deeply important and new about the evolution of sexual autonomy in nature.

This chapter, like the research grant that had its fifteen minutes of infamy back in 2013, has focused on a group of birds in which female mate choice is threatened by male sexual coercion. What happens when mate choice is constrained, prevented, or denied by physical force? we asked. And as we have seen, the female ducks do not simply cave under the threat of violence or even death. Rather, their shared standards of beauty—even meaningless, arbitrary beauty—provide them with the evolutionary leverage to fight back against sexual coercion and reassert their freedom of choice over fertilization. Female ducks teach us a great lesson about the unexpected power of female sexual autonomy. In the words of the Eurythmics and Aretha Franklin song, they teach us that “Sisters are doin’ it for themselves!” By doing so, females together become the agents of choice and the guarantors of their own freedom of choice. The evolutionary advantages of obtaining the mates they prefer—male offspring that will possess the traits they and other females have agreed are attractive—are so strong that they have reshaped female internal anatomy. Expanded sexual autonomy allows female waterfowl to continue to select for beauty in the form of male sexual display and everything that that involves—sounds, colors, behaviors, plumage, and so on. Even in the face of unrelenting sexual attack, female ducks have found a way to maintain the beauty in their world.

It is not an accident that these discoveries are consequences of the aesthetic view of mate choice. Only when we recognize that mate choice is a form of individual agency can we conceptualize sexual violence as a disruption of that agency. To paraphrase Susan Brownmiller, sexual violence is against the will of female ducks too.

The revelation of an aesthetic mechanism for the evolution of female sexual autonomy in waterfowl is a profoundly feminist scientific discovery. It is not feminist by accommodating the science to any contemporary political theory or ideology. Rather, it is a feminist discovery in that it demonstrates that sexual autonomy matters in nature. Sexual autonomy is not merely a political idea, a legal concept, or a philosophical theory; rather, it is a natural consequence of the evolutionary interactions of sexual reproduction, mating preferences, and sexual coercion and violence in social species. And the evolutionary engine of sexual autonomy is aesthetic mate choice. Only by acknowledging that these are real forces in nature can we make progress toward a complete understanding of the natural world. Of course, this should not be too surprising. As Stephen Colbert on The Colbert Report has observed, “Reality has a well-known liberal bias.”

This discussion of duck genital evolution raises a broader question: Why do most birds lack a penis entirely? How did this happen? And what are the evolutionary and aesthetic consequences of the loss of the bird penis? Once again, the concepts of aesthetic evolution and sexual autonomy can provide interesting new insights.

Birds originally inherited the penis from their dinosaurian ancestors, but then it was lost some sixty-six to seventy million years ago in the most recent common ancestor of the group known as the Neoaves, which includes over 95 percent of the world’s species of birds. We do not know anything about the ecology or morphology of the ancestral neoavian bird in which the loss of the penis occurred, so investigating this kind of event is difficult. But that doesn’t mean we can’t make some progress in thinking about it.

The penis could have been lost because it was no longer useful—like the eyes of cave fishes. But copulation is pretty important to reproductive success, so we have to ask what kind of selection could possibly select against the penis?

It’s possible that the neoavian penis was lost because females explicitly preferred males without penises. Why? If one of the primary functions of the penis is to subvert female mate choice through forced copulations, as it is in waterfowl, then female mating preferences against intromission could have evolved to reduce the threat to female sexual autonomy. The next two chapters will focus in detail on how females can use mate choice itself to change males both physically and behaviorally in ways that advance female autonomy. But whatever the evolutionary mechanism, the loss of the penis has had distinct consequences for sexual autonomy in birds.

Going penis-free means that active female participation is virtually required for the intake of sperm into the female cloaca. Although even in the absence of the penis males can mount a female and forcibly deposit sperm on the surface of her cloaca, they cannot deposit sperm within the female nor force her to uptake their sperm by dilating her cloaca. In the more than 95 percent of bird species that are penis-free, females can eject/reject unwanted sperm. For example, barnyard hens can eject sperm after coerced copulations with unwanted males. Attempts at sexual harassment and intimidation do still exist in birds without a penis, and the female birds may still suffer injuries by resistance, but the loss of the penis has resulted in a nearly complete end to forced fertilizations. Through the loss of the penis, female neoavian birds have essentially won the battle of sexual conflict over fertilization.

What are the evolutionary consequences of this expanded sexual autonomy? Interestingly, we can return to Darwin’s observation in The Descent of Man with an entirely new perspective: “On the whole, birds appear to be the most aesthetic of all animals, excepting of course man, and they have nearly the same taste for the beautiful as we have.”

Given that birds are among the few groups of animals that have evolved a combination of complex sensory systems, cognitive capacities, and expanded opportunities for mate choice thanks to the loss of the penis, I do not think it an accident that birds have also evolved into the “most aesthetic of all animals, excepting of course man.” The irreversible advance in avian female sexual autonomy that occurred because of the disappearance of the penis may be the most powerful explanation of the aesthetic evolutionary extravaganza among birds.

This evolutionary extravaganza, which is predicted by the Beauty Happens hypothesis, might in turn have contributed to birds’ explosive speciation and aesthetic radiation, which could help to explain why penis-free birds are the most successful group of terrestrial vertebrates in terms of the number of species. Of course, there are many other factors contributing to avian evolutionary success, rapid speciation, and diversification, including the capacity for flight, their capacity for ecological diversification, migration, song, and song learning. But any future investigation into the question of the evolutionary success and diversity of birds should include the role of aesthetic evolution and the evolutionary loss of the neoavian penis.

Another striking observation about female sexual autonomy in penis-free birds is that it is strongly correlated with social monogamy, in which both the male and the female make substantial reproductive investments of time, energy, and resources into raising their offspring. The traditional explanation for the evolution of monogamy in these birds is that it was a “nonnegotiable” feature of neoavian biology. Unlike most other reptiles, neoavian birds have offspring that are helpless and entirely dependent on their parents when they hatch. These helpless baby birds—what ornithologists call altricial young—are so vulnerable to predation that they must grow up very fast to minimize the risk of being eaten in the nest before they learn to fly. Having two parents helping to raise them will protect them during this vulnerable period and will also speed their development and help them to fledge faster.

Intriguingly, however, we may have this evolutionary logic completely backward. Rather, the loss of the avian penis and the expansion of female autonomy might have had a decisive impact on the evolution of avian development, physiology, and social behavior, so that altricial young may be the result, not the cause, of the evolution of avian monogamy. All species of birds with penises have offspring that can feed themselves soon after hatching—ornithologists call them precocial young—who can be safely raised and guarded by only one parent. (Two-parent care may evolve in precocial bird species if territorial defense is required.) However, once the penis was lost, female birds might have evolved to use their expanded sexual autonomy to require more parental investment from males. Because penis-free male birds cannot force copulation, they are basically required to fulfill female mating preferences in order to reproduce. If females evolve to require greater investment in reproduction from their mates, then males will soon evolve to compete with one another to do a better job of providing resources for the offspring of those choosy females! The result will be evolution of a stronger, more extensive pair bond in which males are active participants and investors in parenting. This expansion of male reproductive investment could in turn have facilitated the evolution of helpless young, whose upbringing requires the kind of substantial investment that males evolved to make. Thus, expanded sexual autonomy that resulted from the loss of the penis has allowed neoavian birds to advance in their sexual conflict with males over parental investment, too.

The concept of sexual autonomy provides insights not only into the evolution of defenses against sexual violence and coercion but into the evolution of other, distinct paths to advance against sexual conflict. We will explore these ideas further, in birds in the next two chapters, and in humans too, in chapters 10 and 11.

So what have the females in the more than 95 percent of bird species that lack a penis done with all the sexual autonomy they have won? As our observations of bowerbirds and manakins in the next two chapters will reveal, they have pursued their aesthetic, and frequently arbitrary, mate choices, and by doing so have contributed to the nearly infinite varieties of colorful, tuneful, and exuberant avian beauty in the world.