CHAPTER 7

Bromance Before Romance

It’s extraordinary enough to realize that female mate choice has produced the explosion of beauty we’ve seen in male manakins and bowerbirds. It’s even more amazing to think that female mating preferences could have had a profound impact on male social relations and that this happened even though, as I’ll discuss in this chapter, much of the resulting male behavior is something the females themselves never witness. But in the case of the manakins, this is exactly what has occurred over the course of evolutionary time. The social relationships among males in a manakin lek have evolved into a virtual bromance—long-term, socially engaged relationships that sublimate and moderate competition—and it’s all come about, I think, because of the female pursuit of sexual autonomy.

Recognizing females as the active agents in the origin of lekking goes against most of the traditional thinking about why the lek-breeding system evolved. But we will see that entertaining this possibility provides a productive new way to understand the complexity and diversity of the highly unusual behaviors of male manakins and of the variations in lek social organization as well.

Although there are fifty-four species of manakins, and therefore fifty-four variations on their breeding and social relationships, we can make a few general observations about manakin leks. To recapitulate the basics: Leks are groups of sexually displaying males. Within the lek, each male defends a specific territory of his own, but the territory includes nothing of value except the opportunity to mate. From species to species, there can be a lot of variation in the size and spatial distribution of these territories and in the number of territories within a lek (from a few to dozens). In some species the territories can be as small as three to fifteen feet or so wide, in others as large as thirty feet or more. In some the territories are closely packed and adjacent, in others more widely dispersed. In a few species, males defend “solitary” lek territories that are so far apart that they are outside visual and acoustic contact with one another. The males may occupy their territories for anywhere between four and nine months of the year, with some populations being on lek nearly the entire year except when the males are molting their feathers. Outside the manakins, leks have evolved in a wide variety of other birds, in various insects, fishes, frogs, and salamanders, and in a few ungulates and fruit bats.

Confusion about the nature and function of leks dates back to Darwin himself, who was divided in his assessment. He discussed avian lek behavior in several sections of The Descent of Man. In “The Law of Battle” section he interpreted it in the context of male-male competition, which is how most evolutionary biologists have discussed it ever since, down to this very day. But in the “Vocal Music” and “Love-Antics and Dances” sections he wrote about lekking birds in the context of female mate choice. For over a century, Darwin was unusual in considering even the possibility that leks could have anything to do with female choice.

In the absence of a working theory of female mate choice or sexual autonomy, it’s not surprising that theorists of the evolutionary origin of leks have generally conceived of lek organization as a purely male-male competition phenomenon—a product of the struggle for male dominance or control. The traditional hypothesis is that the males within a lek fight it out ritualistically in order to establish a hierarchy, and the females acquiesce to mate with the dominant male. Females would thereby win the male who was by definition “the best,” because he had fought his way to the top of the hierarchy. This fit in well with the Wallacean notion that all sexual selection is a form of adaptive natural selection.

The male competition concept of lekking might have reached its most extreme expression in the popular ornithology textbook that I used in college, The Life of Birds by the Beloit College professor Carl Welty. Welty compared avian leks to the medieval European droit du seigneur (or lord’s right), in which the lord of the realm had the right to have sex with any virgin bride in his realm before her wedding. With his colorfully inapt analogy, Welty managed to equate a possibly mythical human cultural institution, which embodies the ultimate denial of female sexual autonomy, with an avian social system—the polygynous lek—that, as we will see, may be the premier example of female sexual autonomy in action.

In an influential 1977 paper, the behavioral ecologists Steve Emlen and Lew Oring espoused the traditional male-male competition theory of lekking, describing leks as “a forum for male-male competition,” which made it possible for “females [to] choose primarily on the basis of male status.” Recognizing the apparent evolutionary problem with this theory—after all, what’s ultimately in it for males to join a lek, because most of them will lose the competition?—Emlen and Oring came up with a plausible-sounding explanation. They hypothesized that by gathering together to pool their advertisement signals, the males will be able to produce a louder invitation that will reach farther, and attract a larger total number of females per male, than they could with individual advertisements. However, the animal behaviorist Jack Bradbury soon demonstrated that males cannot actually gain by pooling their visual or acoustic display signals. Even though larger groups of displaying males do make a total advertisement that is louder than that produced by a smaller group, the volume increase is only incremental—in direct proportion to the number of males. This means that additional males that join a lek do not increase the per male effective broadcast area of the lek. Joining a lek will not result in any net gain in an individual male’s broadcast efficiency or in the number of females he is likely to attract.

If males do not benefit by pooling their displays, then what other reason could there be to join a lek? Bradbury and others proposed several possible models based on advantages they believed lekking might be able to offer to the male. For example, the “hotspot” model predicts that males who aggregate in areas of high traffic for foraging females will be able to maximize their encounter rates with females. Then there’s the “hotshot” model, which predicts that males who establish territories near other particularly attractive males—the “hotshots” who attract higher than average numbers of females—could benefit because some of the females may end up mating with one of them instead.

However, the evidence for both the hotshot and the hotspot hypotheses is mixed at best. With the use of exciting new scientific tools and techniques, including radio tracking and molecular fingerprinting, in combination with good old-fashioned, high-efficiency nest finding, a number of recent studies suggest that these theories are just flat-out wrong. For example, Renata Durães and colleagues found that some Blue-crowned Manakin (Lepidothrix coronata) leks were indeed located in areas of high female traffic, but contrary to the hotspot hypothesis these leks were smaller, not larger, than leks in low-traffic areas. In a subsequent study, Durães captured and analyzed the DNA “fingerprints” of a population of the male and female Blue-crowned Manakins. She found an incredible sixty-six active nests and obtained molecular fingerprints of the nestlings to identify their fathers and then determined how far the females had traveled from their nest sites to find a male to mate with. Durães found that most females did not choose a mate from the nearest lek, but on average selected a mate from the third-nearest lek, which contradicts the hotspot model. Durães concluded that female mate choice was not consistent with either the hotspot or the hotshot model.

In the 1980s, Jack Bradbury and the evolutionary biologist David Queller were among the first since Darwin to propose that the formation of leks had anything to do with female mate choice. In 1981, Bradbury proposed the revolutionary hypothesis that leks evolve because of female preference for male aggregation. Specifically, he suggested that females have evolved preferences for males concentrated in leks because having a number of males in proximity to each other enables them to make efficient comparisons of potential mates. Shopping for a mate is much easier and more convenient when there are a lot to choose from in a relatively small amount of space. It’s sort of like shopping at a mall instead of having to travel greater distances from store to store.

David Queller went even further with the female choice idea and proposed a purely aesthetic, sexual selection model of lek evolution. Queller showed that leks can evolve if social aggregation is like any other male display trait—say, tail length. Once there exists a female preference for the trait, in this case aggregated males, male aggregations will evolve. Genetic variation for a mating preference for leks will become correlated with the genetic variation for lekking, and preference and trait will continue to coevolve with each other. According to this model, lek evolution is just another kind of arbitrary beauty, but one that pertains to male social behavior rather than to male physical features.

Bradbury and Queller both viewed leks as organizations that had evolved to provide a mechanism for female mate choice. Unfortunately, their emphasis on the female as the active agent was so far ahead of its time that their revolutionary models did not receive a lot of attention. And after a boom of interest in the evolution of lek behavior during the 1980s and 1990s, most of which—unlike Bradbury’s and Queller’s—focused on the many attempts to support the hotspot and hotshot models, research on the question slowed to a trickle.

The biggest weakness of the current models of lekking—both the male-competition and the current female-mate-choice models—is that they focus only on the lek as the place where mating occurs. They fail to take into account the fact that the lek is also a male social phenomenon. Leks are not merely convenient concentrations of territories where females can find their mates. Unlike clusters of competing gas stations and fast-food restaurants located just off the exit of a highway where motorists can easily find them, leks are highly social organizations in which a number of males gather, defend territories, fight, engage in often elaborate cooperative displays, and develop complex and enduring social relationships that can last a lifetime.

To understand just how elaborate these relationships are, we must take a look at the rather bizarre social lives of the males, which are in marked contrast to those of the females of the species. After hatching and fledging from the nest, female manakins live entirely independently. They have no social relationships with other adult females or with any adult males except during those few brief minutes of the year when they are visiting the displaying males, selecting a mate, and engaging in copulation. Their only other relationships of any kind are with their own dependent offspring, and those relationships end as soon as the chicks leave the nest.

The males are a different story entirely. Their relationships with females are minimal, as noted—confined to the short period of time they spend in the nest with their mothers, to the one- or two-minute visits they receive from various females visiting their territories during breeding season, and, if they are attractive enough and have sufficiently good displays to win the favor of one or more of these females, to brief mating sessions. But they do enter into complex, interactive, and long-lasting relationships with other males.

Once the young male manakins fledge and leave the nest, they roam around for a year or more (depending on the species), during which they must establish and defend a display territory within a lek of other males. Then they begin to develop the social relationships that are a characteristic of lek behavior. Because each manakin male typically defends the same territory in the same lek every breeding season for years on end, often for the duration of their lives, which can last a decade or even two, these relationships have the opportunity to develop over extended periods of time. So, social relationships between males on the lek consist of daily social interactions that typically continue for a decade or more.

So, why do males participate in leks? The best explanation is that males must aggregate because the females prefer it. In polygynous species like manakins, as we’ve seen, females do all the work of parenting entirely by themselves. They build the nest, lay the eggs, incubate the clutch, and feed and protect the nestlings until fledging. In exchange for all their efforts, females have gained control over fertilization. Males have no choice but to submit to female preferences because any renegade male that refuses to join a lek will lose any possible prospect for reproduction. The females are in charge, and male rebellion will lead to sexual irrelevance.

Is there any reason why independently living females who mate once a year would not prefer the kind of rich and complex aesthetic/sexual experiences afforded by a lek? Why not have sex the way you want it—amid a complicated, intense, stimulating circus of display activity? From the female’s point of view, we can think of the lek as being like a brothel, but in reverse because it caters to females instead of males. Each male candidate for her sexual favor puts on an elaborate performance to woo her into choosing him. Even better, unlike the transactions that occur in a real brothel, the customer doesn’t have to pay. Any male she wants is hers for the asking, free of charge.

The initial female preference for spatially aggregated males might have been a simple sensory/cognitive bias for greater, more intense sexual stimulation of the kind that occurs from observing multiple singing and displaying males in proximity. So it makes sense that lekking could evolve as a way of gratifying this kind of desire. But as noted earlier, leks are not just aggregations of male mating territories; they’re also places in which males have developed elaborate social relationships with each other, which seems a very odd evolutionary development. After all, the males of almost all species are sexual competitors and frequently aggressive with each other. Evolving male cooperation is hard. In fact, any form of cooperative animal behavior presents a challenge to explain evolutionarily. Whether it’s altruism in social insects, the development of human language, or the phenomenon of helpers at the nest, the evolution of cooperative behaviors always requires overcoming the substantial hurdle of the benefits of individual selfishness.

And make no mistake—this is a huge evolutionary challenge. The relative mating success of each male will be increased by aggressively interfering with the mating attempts of every other male. But such constant disruption would destroy the lek. Females would never be able to choose a mate if males are aggressively disrupting and fighting one another all the time. How, then, can leks ever evolve and survive if it is in the best interest of every selfish male to try to prevent every other male from mating?

The key to understanding this conundrum is to realize that male disruption of visits by females to other males within the lek is a form of sexual coercion against females, infringing on their sexual autonomy. In essence, one evolutionary mechanism, female mate choice, is being pitted against another, male-male competition. For female choice to prevail, manakins have to somehow get around male aggression.

How do they manage this? As in bowerbirds, female manakins have used their mating preferences to remodel male behavior in order to get what they want. In bowerbirds this reengineering takes the form of the bowers that protect the female from unwanted copulations while she’s evaluating the male and deciding whether he’s the one she will choose to father her offspring. Male bowerbirds are still highly aggressive to each other and even to visiting females, but the bowers that they themselves have built serve to mitigate the impact of much of that aggression on female freedom of choice.

In manakins, by contrast, the resistance to sexual coercion has been expressed not in architecture but in a fundamental reengineering of male social organization and behavior. The resulting transformation has greatly reduced male aggression and thereby maximized the female’s chances of getting what she wants. It has also resulted in a lek-breeding system that is stable because it is not constantly disrupted by male aggression. Although fighting and disruption among males are not entirely eliminated, they are reduced to some tolerable balance between female freedom of choice and male competition.

Thus, I hypothesize that lekking is not an exhibition of male dominance hierarchy, and of female acquiescence in it and the adaptive benefits it offers, as was theorized for most of the twentieth century. Rather, leks are likely the result of female preferences for socially cooperative aesthetic gatherings of males.

What evidence is there that leks, particularly manakin leks, evolve as cooperative social phenomena? In fact, this evolutionary hypothesis is quite hard to test. Clearly, males in lekking species are much more spatially tolerant of each other than are other territorial birds. So, we know that manakin and other lekking males are socially distinct in some fundamental way. But it is hard to know whether female choice has been responsible for this transformation in male social behavior. Luckily, one highly unusual variation on lek display behavior that is very prevalent among manakins provides telling insights into the fundamentally cooperative nature of lekking.

In many manakin species, the social relationships among males may go well beyond mere peaceful proximity. Rather, male-male social relationships can extend to participation in highly elaborate coordinated displays among two or more males that can require years of fine-tuning to perfect. The specifics of such displays can vary dramatically depending on the species, but this kind of coordinated and cooperative behavior is a feature of many male manakins.

Although the aesthetic nature of these coordinated displays is highly diverse, when it comes down to a question of social function, there appear to be two classes: There are coordinated displays, which are performed by pairs of males, almost always when females are not present. And in the case of one particular genus of manakin (Chiroxiphia), there are what I call obligate coordinated displays, which are done by pairs or groups of males in the presence of females and which are an obligatory prerequisite of mate choice and mating. No male Chiroxiphia manakin can hope for a chance at mating with a female unless he participates in such a coordinated, multi-male display.

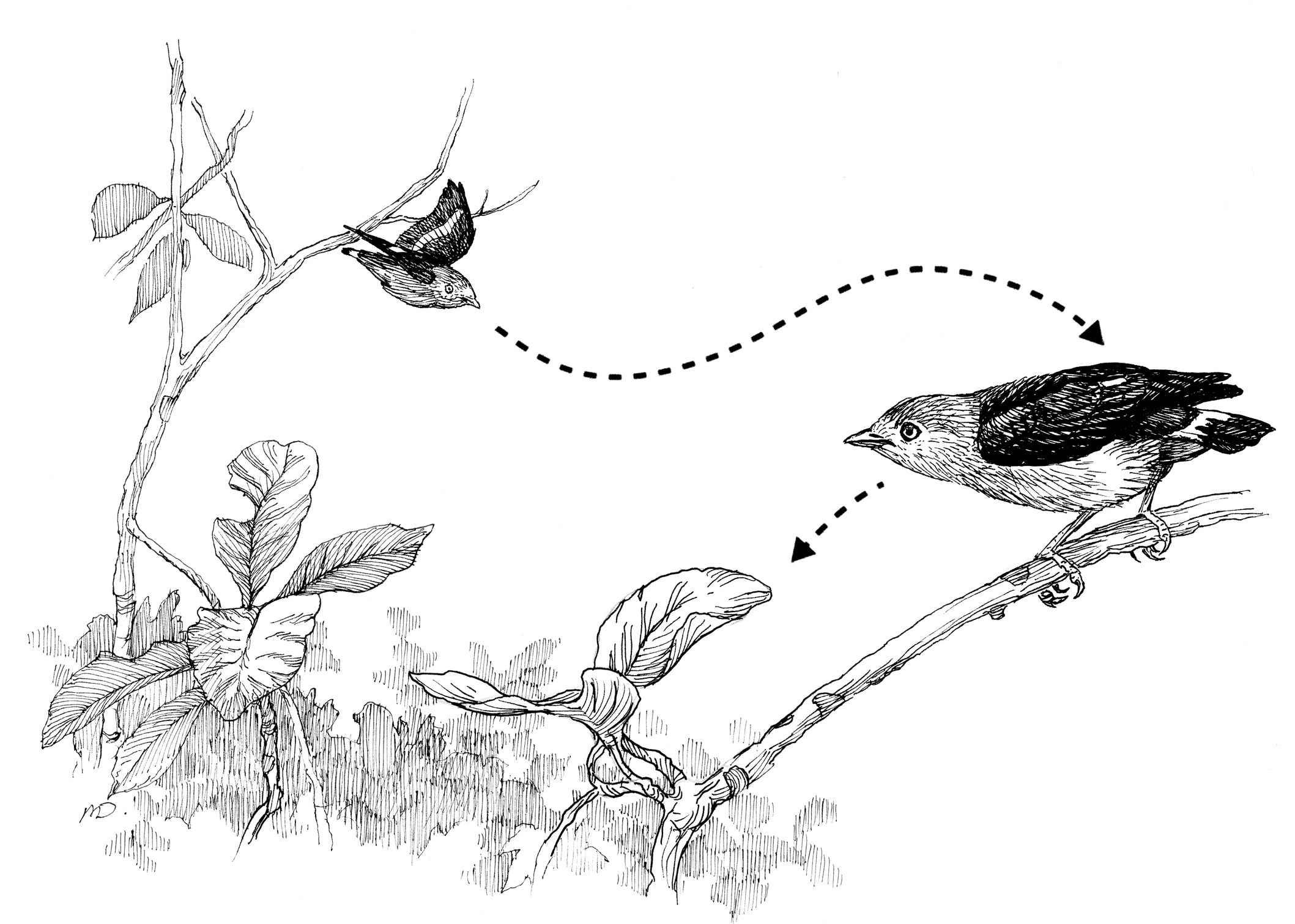

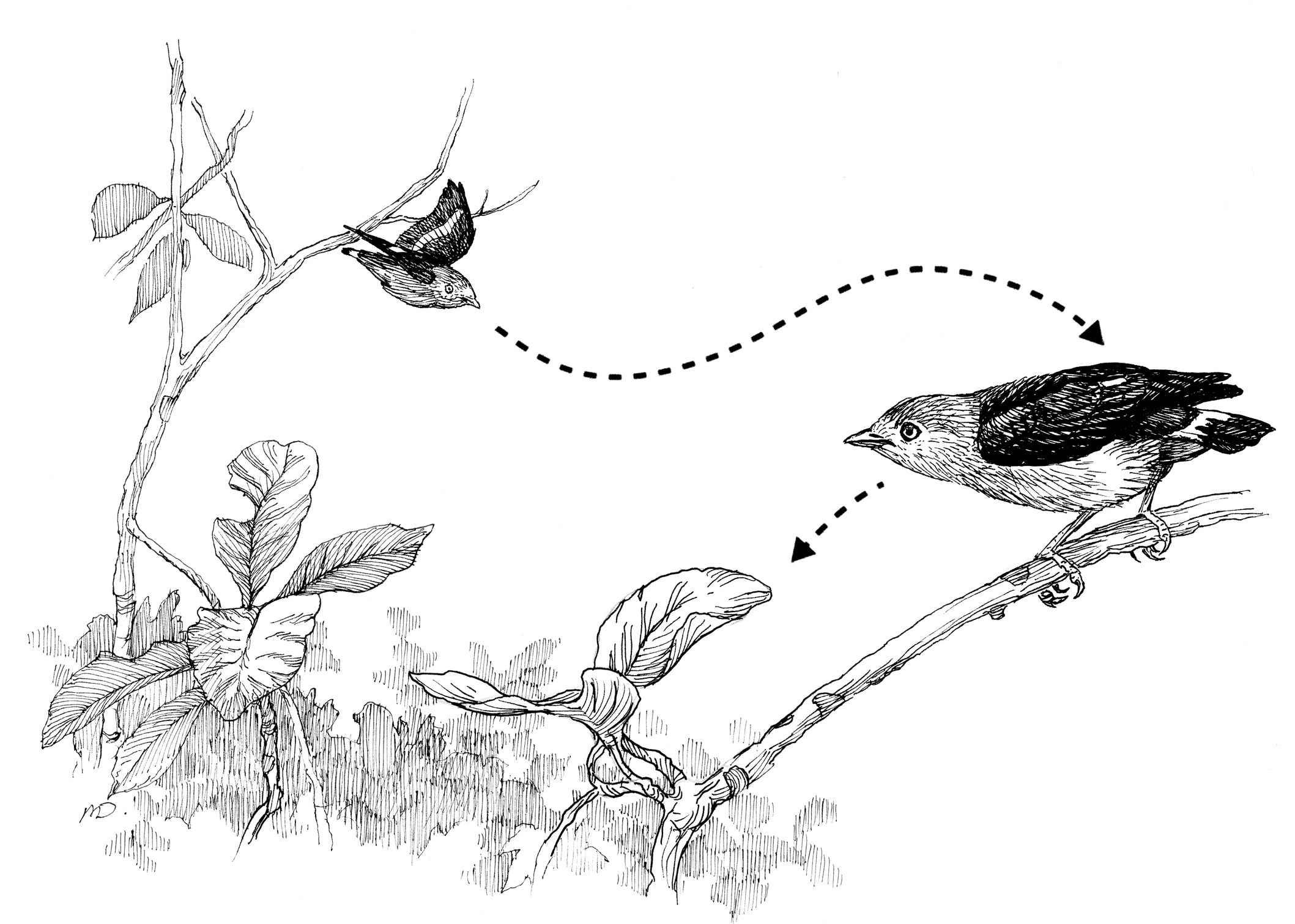

As dances, the coordinated displays are wonderfully variable. For example, as described in chapter 3, pairs of territorial male Golden-headed Manakins perform an elaborately choreographed series of maneuvers, after which they will sit side by side on the same branch, facing away from each other in a bill-pointing posture. In Blue-crowned Manakins and White-fronted Manakins, the males perform a coordinated version of the same display elements that they perform solo when females visit. These displays consist of “beeline” and “bumblebee” flights back and forth between saplings and chasing each other around a small court near the forest floor.

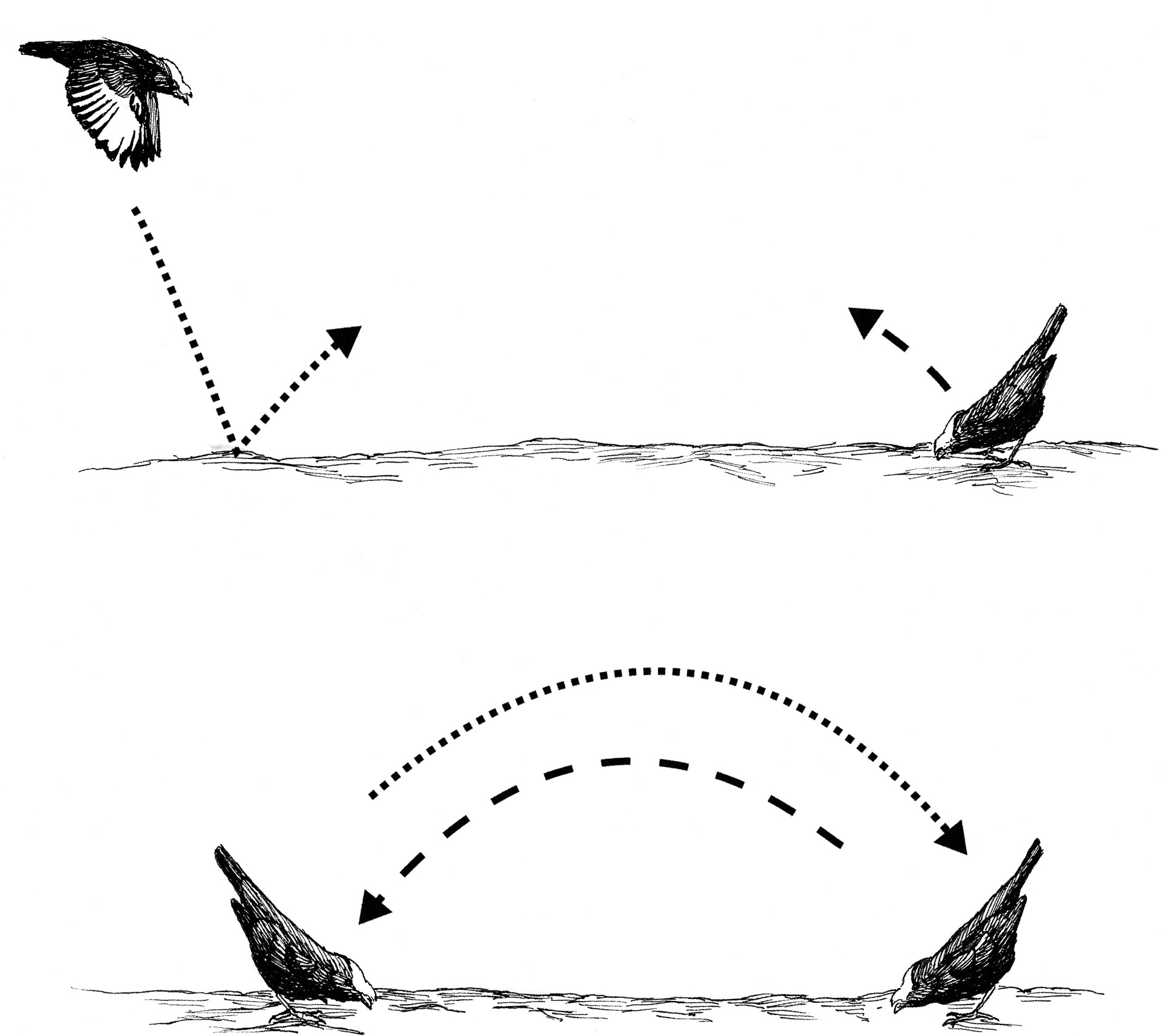

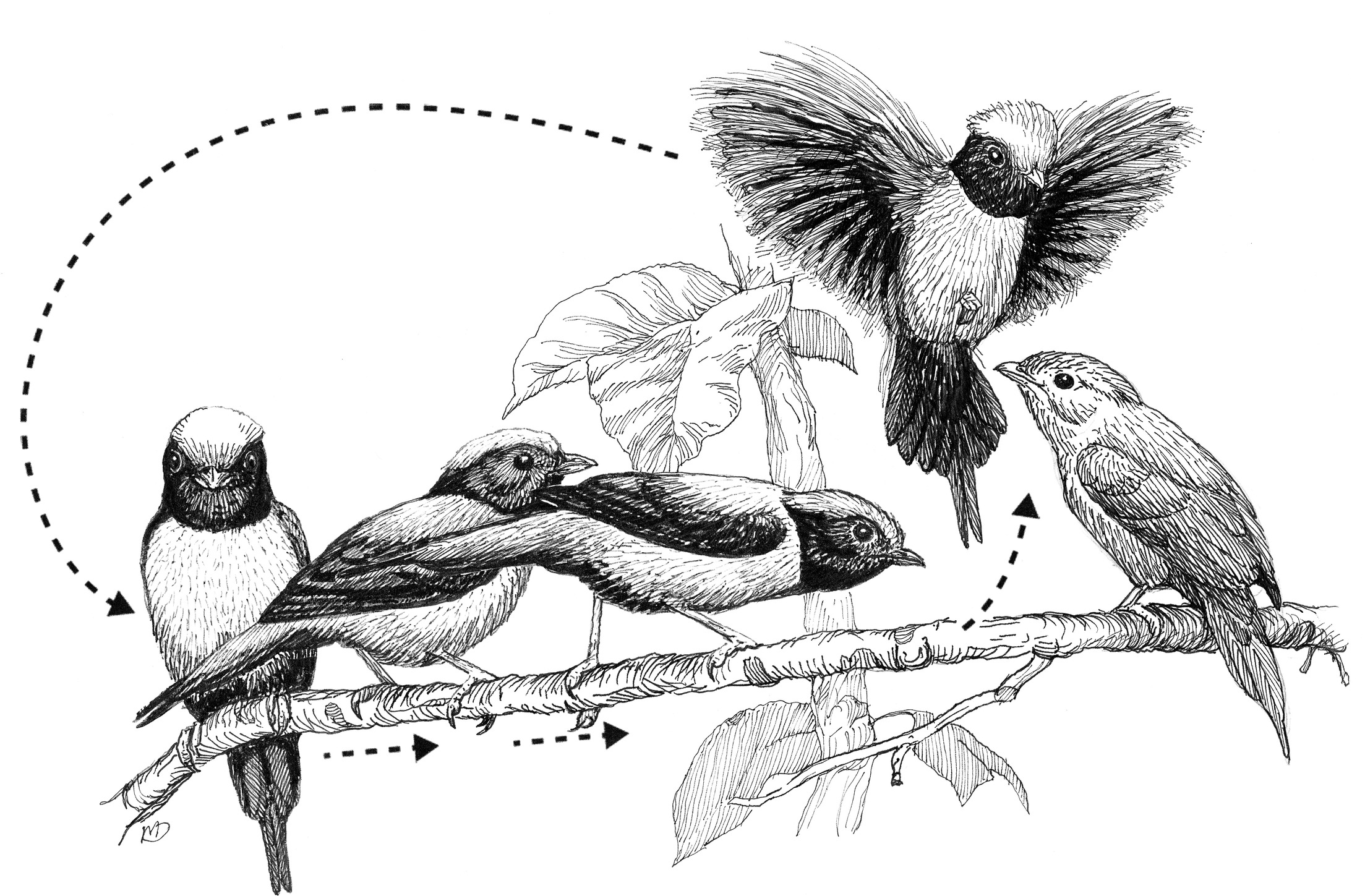

In the Golden-winged Manakin, pairs of males perform a coordinated version of the spectacular log-approach display described in chapter 3. The first male waits on the log for the second male to perform the log-approach display, and as soon as the second male arrives, he leaps up into the air and allows himself to be replaced on the log. Then the roles are reversed, and the second male waits for the first. In this case, the coordinated display is performed by pairs of males that may be made up of neighboring territory holders or of a territorial male and a younger, floating non-territorial male. None of the joint displays I’ve just described are performed during female visits to male territories; they merely function in male-male social relationships.

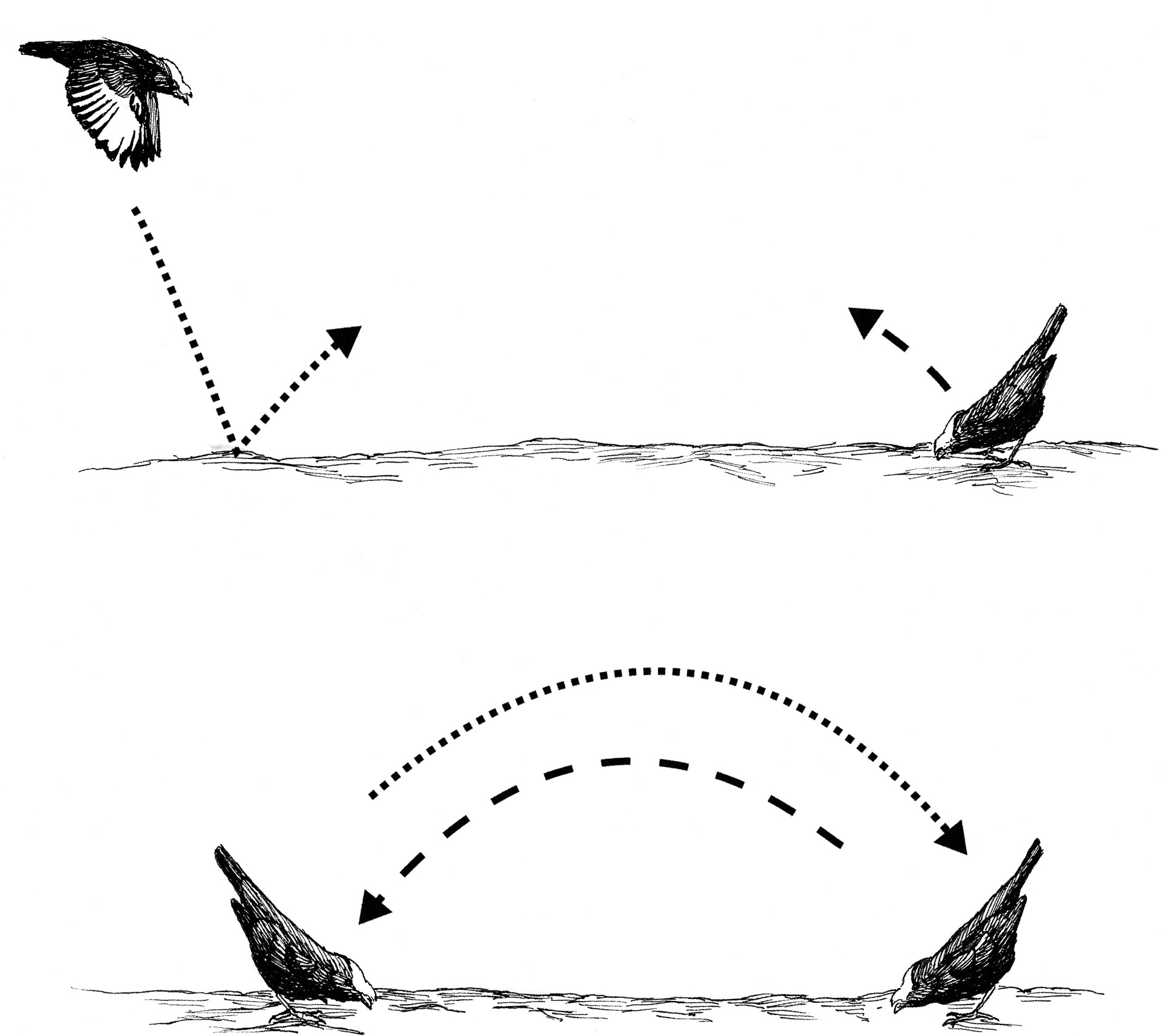

The ornithologists Mark Robbins, Thomas Ryder, and others have added to our knowledge of the social relationships among manakins with their descriptions of coordinated displays of males in the genus Pipra, which includes the Wire-tailed Manakin (Pipra filicauda), the Band-tailed Manakin (Pipra fasciicauda), and the Crimson-hooded Manakin (Pipra aureola). A territorial Pipra male displays with a number of other males, including both other territory holders and younger, non-territorial, “floater” males. Typically, a coordinated display consists of a territorial male waiting on his main display perch, while a second male performs an S-curved, swoop-in flight display, swooping below and then above the level of the display perch as he approaches it. When he lands on the perch, he produces a distinct call as he displaces the waiting male. The display is then repeated with the roles reversed, over and over again. Such coordinated flight displays can continue for several minutes without stopping. As with the displays described above, these joint displays are not usually performed for visiting females. They draw on the same vocabulary as intersexual communication—that is, the particular display elements are the same as those that a solitary male would perform for a visiting female—but they incorporate the elements into joint performances that are entirely male-male social behaviors.

Coordinated display of a pair of male Golden-winged Manakins. (Top) One male waits on the log in tail-pointing posture as another flies toward the log. As the flying male lands and rebounds off the log (dotted line), the waiting male leaps off the log (broken line). (Bottom) The two males cross in the air over the log and land facing one another in tail-pointing posture.

All of the displays I’ve just been describing are of the first functional type—the simply coordinated. The second special class of this behavior, the so-called obligate coordinated display, is unique to the blue Chiroxiphia manakins. Chiroxiphia males engage in the most extreme form of precopulatory male-male cooperation known in any animal. Pairs, or even larger groups, of males with long-standing relationships with each other perform coordinated displays that are a largely obligatory part of the courtship of females. Unlike other manakin females, Chiroxiphia females observe these coordinated performances and make their mating choices based on their evaluations of them. Once they decide which pair or group’s performance they prefer, they have the opportunity to select the dominant, alpha male of the group.

The coordinated swoop-in flight display of a pair of Band-tailed Manakins.

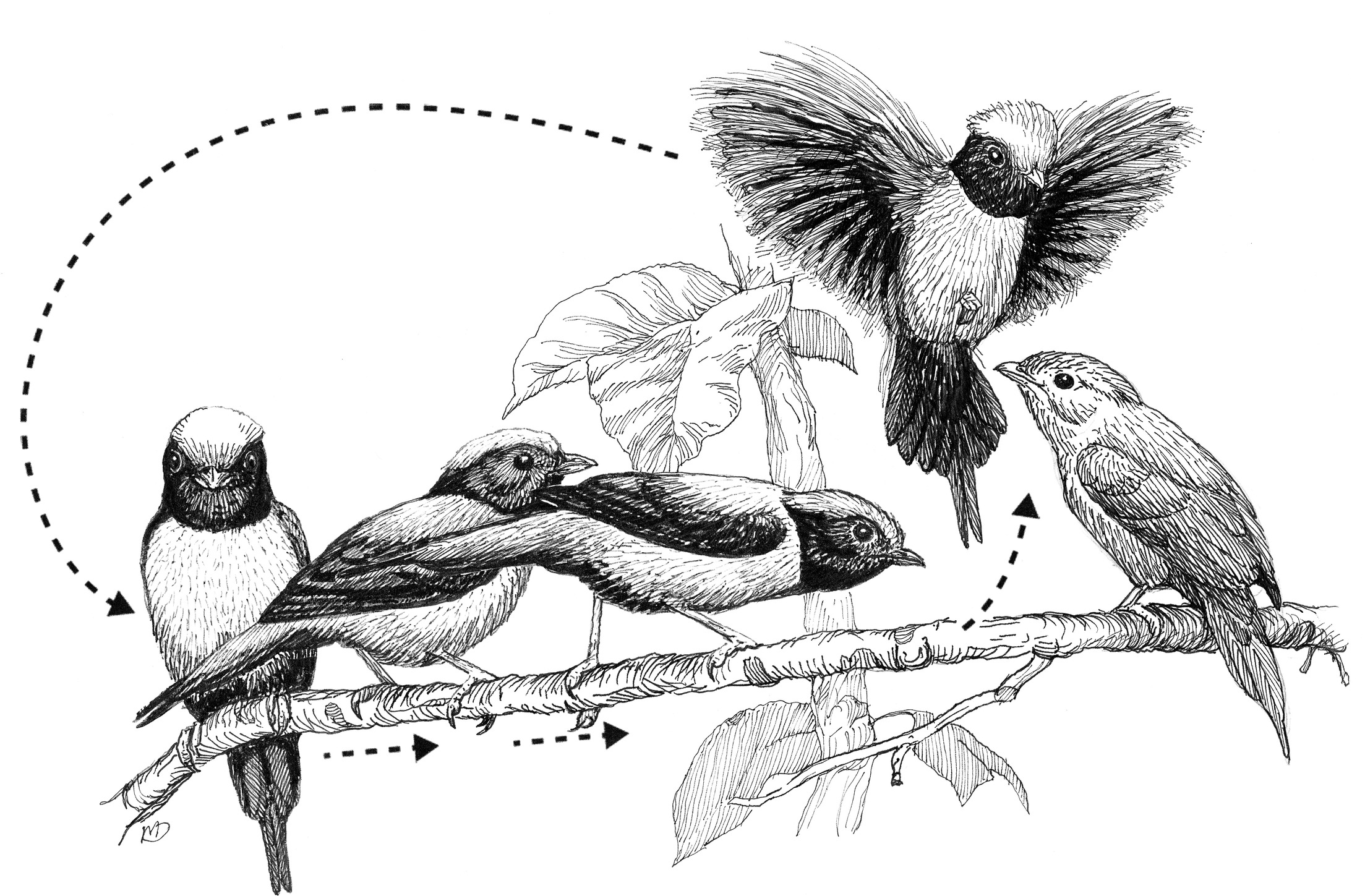

To attract female visitors to the display site, Chiroxiphia males first sing loud, highly coordinated duets from perches high above the display perch—Toleedo…Toleedo…Toleedo…(or similar syllables). Then, when females visit, pairs or even groups of males perform an elaborate “cartwheel” or “backward leapfrog” display. In most species, the backward-leapfrog display is performed by two males perched on a small, concealed horizontal branch located near the ground. In the Blue Manakin (Chiroxiphia caudata), the backward-leapfrog display is performed by a group of up to four or five males (color plate 20)! After the female has landed on the display perch occupied by the males, the male who is closest to her leaps upward and hovers in the air in front of her with his red crown fluffed. While hovering, the male gives a buzzy, snarling two-syllable call in flight and then flutters back down to the perch, taking a position farther away from the female. Meanwhile, the second male slides forward along the perch toward the female, then leaps up and performs the same display as the first. These leapfrog displays are repeated anywhere from twenty to two hundred times, depending on how much the female likes what she observes and how many bouts she’s willing to watch. Eventually, the dominant, alpha male of the group gives a distinctive call, and the subordinate, beta male(s) leaves the perch. The alpha male does a few more distinct displays and then, if the female is still there, copulates with her on the display perch. The female may decide to leave at any point during the display sequence.

The obligate coordinated display of a group of male Blue Manakins for a visiting female (perched at right). As the male closest to the female leaps up and flutters back down the branch, the perched males sidle up the branch toward the female. The cycle is repeated dozens or even hundreds of times.

Considerable skill and coordination are involved in putting on these performances. Because the females are extremely discerning, their preferences select for males who have been in male-male social relationships that have lasted long enough to have allowed them plenty of time to practice diligently and iron out any kinks in their performances. Apparently, it can take years of practice to achieve vocal coordination between males that is good enough to attract mates. The ornithologists Jill Trainer and David McDonald have shown that the timing of the vocal coordination in the Toleedo…Toleedo…duet sung by male pairs of Long-tailed Manakins greatly influences their chances at sexual success.

This cooperative mode of display behavior has reorganized the entire breeding system of the Chiroxiphia manakins, resulting in a distinctly new form of lek. Chiroxiphia males do not defend individual territories, as other manakins do. Rather, each display territory is controlled by a team of males. The team consists of a dominant, alpha male who shares the territory with a subordinate beta—or in the case of Chiroxiphia caudata, with beta, gamma, and even epsilon males—all of them aspiring one day to succeed him as alpha male. The male partnerships within these shared territories are long-lasting and established over the course of years of interactions.

But the road to this kind of partnership is filled with challenges for the wannabe alphas. The young males must compete with each other as each of them strives to become an established beta male or alpha territory holder. And before they can even enter the competition, they must wait out the four-year period it takes for them to achieve mature adult plumage. At first, the young males look like green females, and each year they molt into a successively more male-like plumage. During this period, the subadult males consort with various groups and participate in rudimentary displays. Once they achieve adult plumage, males typically spend several more years displaying as floaters, trying to win the approval of an alpha male whom they can partner with. During this apprenticeship time they continue to work on improving the temporal coordination of their duetting songs and displays.

When at last a Chiroxiphia manakin achieves beta male status, what does he get for his time and effort? Well, he still doesn’t get to mate with a female, because females choose only among the available alpha males. But at least he’s now in a better position to inherit the alpha position if the alpha male dies or disappears—although that can take five to ten or more years to occur. If and when a male finally achieves alpha status, the struggle is not over, because there will still be constant competition with other alpha males in different display partnerships to succeed at attracting the most mates.

The intense, multi-tiered competition creates the strongest sexual selection measured in any vertebrate animal. For example, in his long-term study of Long-tailed Manakins (Chiroxiphia linearis) in Costa Rica, David McDonald was able to show that a very few males may obtain fifty to a hundred copulations per year for five or more years, while most males never have any opportunities to mate. The behavioral ecologist Emily DuVal found something similar when she conducted a remarkably exhaustive study of sexual selection in the Lance-tailed Manakin in Panama. By using the DNA fingerprints of chicks in the nest to establish paternity, DuVal documented that all young were sired by alpha males. Furthermore, out of a single age cohort of twenty-one males, only five of them became alphas, and four of those five were responsible for siring fifteen offspring, while the rest sired no chicks at all over a period of nine years. Clearly, Chiroxiphia females have such strong mating preferences that there will be far more losers than winners in the sexual competition. Chiroxiphia society is like a giant Ponzi scheme in which over 90 percent of males must lose.

So why do they do it? Obligatory male-male cooperation is a total loss for the vast majority of males. The only reason it can happen is that females are completely in charge. Males have no options because there is no other game in town. Like the judges of a male-pairs figure skating competition—or better yet, of a male-pairs pole dancing contest—females can be as picky as they want to be, or as picky as they have evolved to be. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the prize for extreme aesthetic expression goes to the Brazilian team! The Blue Manakin performs the cartwheel display in groups of three to five males and does so in the forests surrounding the Carnival capital, Rio de Janeiro, in southeast Brazil. There is no other show like it on the planet.

Male Chiroxiphia manakins are engaged in the most ruthless sexual competition known in nature. But this competition is not fought out with antlers or aggression. Rather, it is enacted entirely through a system of ritualized cooperative male dance. Extreme female choice has led to a transformation of males from aggressive competitors into disco slaves of fashion.

Traditionally, coordinated display behaviors have been interpreted (even by me in the 1980s) as a mechanism for males to ritualistically establish a dominance hierarchy. This view, however, is a hangover from the concept of leks as sites where males compete to establish a dominance hierarchy and females then acquiesce to the alphas. In fact, there is little evidence that male dominance per se contributes to sexual success among manakins. Another possible explanation for male coordinated display is kin selection. Perhaps males are displaying with close relatives to enhance the reproductive success of the genes shared with their half brothers or cousins? However, David McDonald and Wayne Potts have conclusively established that the males within displaying partnerships of Long-tailed Manakins are not more closely related to one another than by chance alone. These and other male-advantage explanations simply fail.

By contrast, the female choice/sexual autonomy model of lek evolution can explain both the evolution of lekking itself and the many varieties of socially coordinated manakin lek behavior. Coordinated display in manakins is an elaboration of the inherently cooperative nature of male lek behavior in general. It’s another expression of the taming of the selfish aggression of individual males that makes leks possible in the first place. And it has likely evolved through the same mechanisms that created lekking—female mating preferences for cooperative male behaviors that contribute to female freedom of choice.

What’s at first puzzling about this hypothesis is that the coordinated male-male display behavior of most manakin species is rarely, if ever, observed directly by visiting females. Thus, the evolutionary effect of female preferences on coordinated male social behavior must be indirect. If the females don’t observe this behavior, why do they prefer males who engage in it? Basically, what’s it to them?

It appears that by choosing males that get along socially with one another, females are selecting indirectly for males that perform coordinated displays. Males involved in such cooperative relationships are less likely to engage in violent mating competition, and females can thereby avoid harassment, which would waste their time and disrupt their mate choices. Thus, coordinated display evolves because these male-male interactions nourish the complex social relationships that females have forced upon them.

However, like other serendipitous consequences of aesthetic evolution, once cooperative display exists, it can become subject to sexual selection and lead to new forms of mating preferences. This mechanism could account for the evolution of the unique form of obligate cooperative display found in Chiroxiphia manakins. Perhaps coordinated male displays occurred so frequently in the ancestors of Chiroxiphia that females began to select specifically on this stimulating new form of male-male display, and their preferences then coevolved with these novel behaviors. Thus a once-incidental social behavior became an integral component of the display repertoire, yet another example of the evolutionary cascade of effects that can be created by aesthetic mate choice.

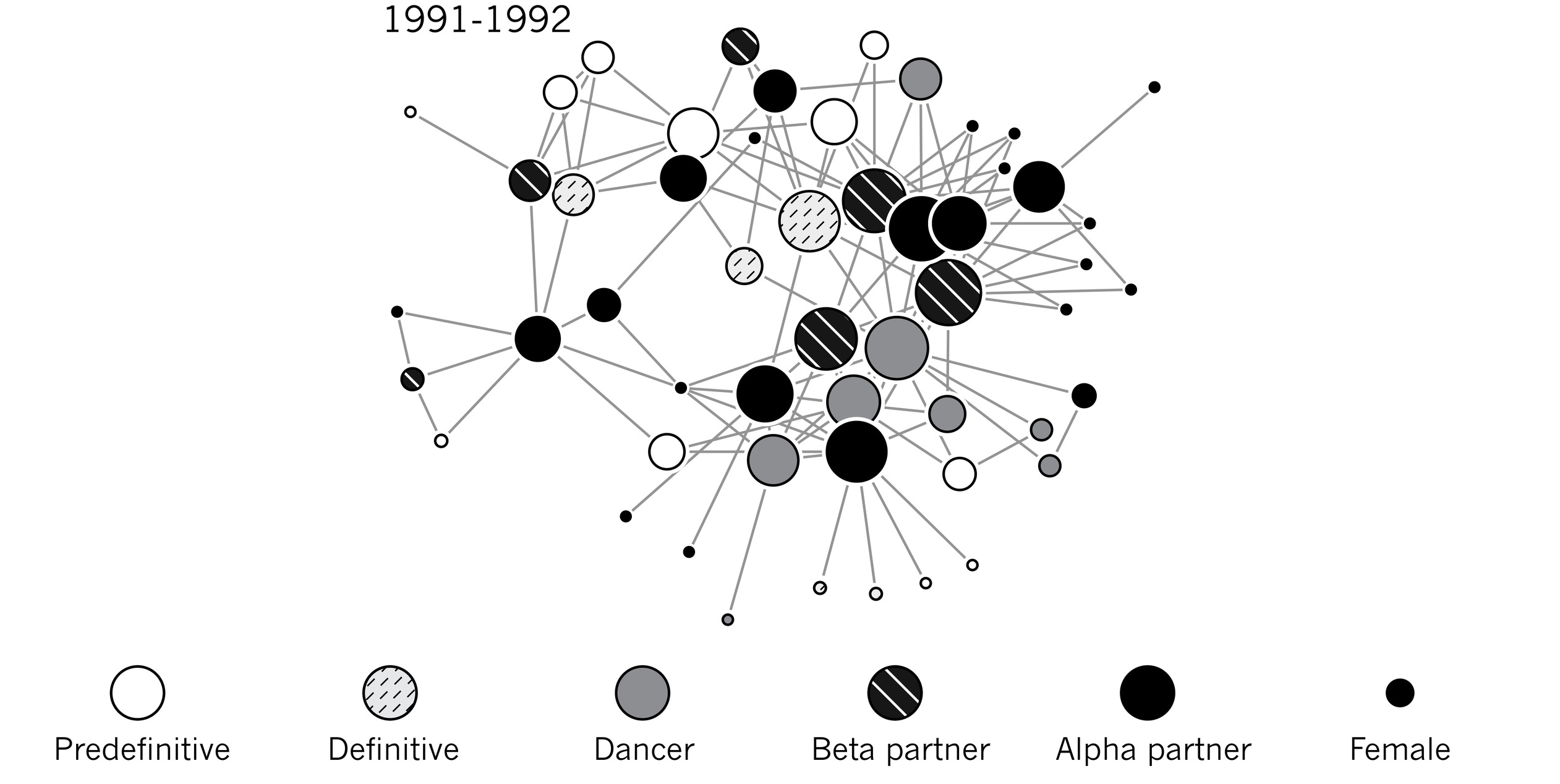

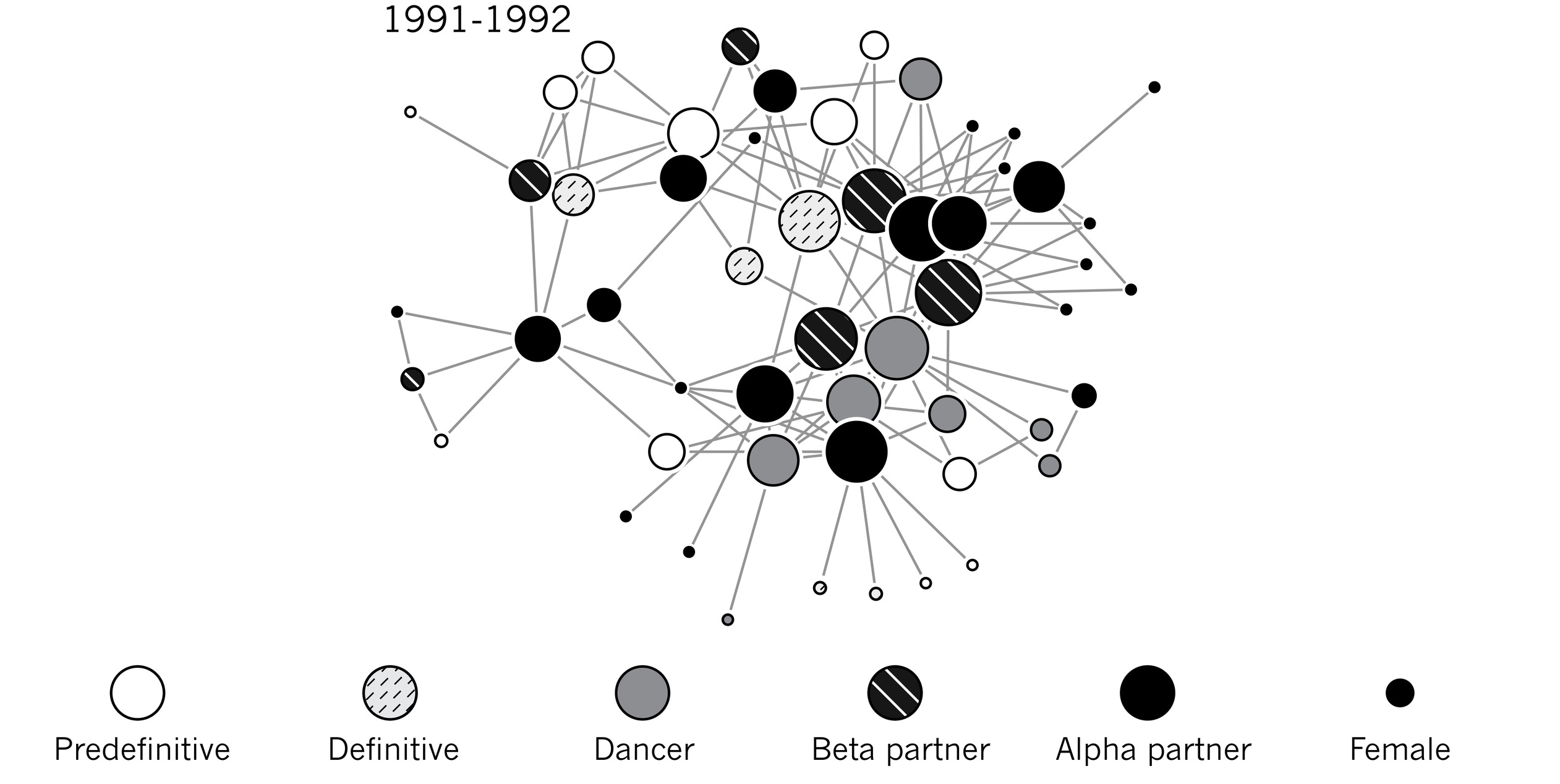

How can we test the hypothesis that coordinated display evolved as an essentially cooperative social behavior through female mate choice? Two interesting new data sets that employ an entirely novel perspective on manakin social relationships offer strong support for this idea. Recently, David McDonald has pioneered the use of network analysis to track the social relationships among male lekking birds. Network analysis is a way of describing the social interconnectedness of individuals via a graph of nodes (that is, individuals) connected by lines (that is, relationships). Law enforcement, security, and intelligence agencies are using network analysis tools to discover and track criminal and terrorist groups from cell phone records, e-mails, and metadata. This same technique can also help us investigate the role social relationships play in the sexual success of male manakins.

Using a ten-year data set from the obligately coordinated, cartwheeling Long-tailed Manakin, McDonald showed that the best predictor of a young male’s future sexual success was the extent of his connectedness to the male social network. In other words, those young males with the richest social relationships—that is, the ones most consistently engaged in display relationships with lots of different groups of males—were most likely to ascend to alpha male status and to higher sexual success in later years. Similarly, Bret Ryder and colleagues have documented that the degree of social connectedness among young male Wire-tailed Manakins is a strong predictor of social advancement and subsequent sexual success.

These data demonstrate that rich male social relationships—bromance, not dominance and aggression—are the paths to male sexual success in the manakins. The loners and the antisocial males that cannot get along with others will be the sexual losers within a manakin lek.

Of course this raises the question of how female Wire-tailed Manakins know which males have the richest social lives, because they rarely if ever see the coordinated male performances and presumably don’t have access to tallies of the number of Facebook friends each male has. However, while females can only select directly on male display behaviors that they see and evaluate, they also select indirectly for males with the most complex and sustainable social relationships. If practice makes perfect, perhaps by choosing the best displayers, females are also choosing those males who have engaged in the most varied, frequent, and enduring social collaborations. So if we ask, what goes into social and sexual success among manakins, the answer is probably a combination of genetics, development, and social experience.

The social network of male Long-tailed Manakins for a single year identified by social status. From McDonald (2007).

In manakins, female mate choices have fundamentally reshaped the nature of an all-male world they rarely visit in order to advance both female sexual fancy and freedom of choice. The result has been the evolution of the lek itself and of the numerous and astonishing variations in coordinated male display found in so many species.

Nearly 150 years after The Descent of Man, we must wonder whether Darwin’s statement—“Birds appear to be the most aesthetic of all animals, excepting of course man”—went far enough. If we measure the aesthetic accomplishment of an individual or a species in terms of the share of energy and investment dedicated to aesthetic expression, then manakins far exceed humans. All manakin males—half of the species—expend most of their time and energies in the rehearsal, perfection, and performance of a set of highly choreographed song and dance routines, in duet, group, and solo forms. By Darwin’s criteria, the manakins and bowerbirds beat humans by far!