Students simply do not appreciate how much time teachers put into their classes. Little do they realize that the hours they spend in class are matched by hours outside. Good teachers labor over every problem they explain in class. The order, difficulty, and complexity of each exercise is carefully planned. Apparently little has changed in almost four thousand years.

We can learn a lot about ancient mathematics by looking at texts from a pedagogical point of view. Far too often historians of mathematics select one interesting problem and analyze it to death. By taking these problems out of context, they lose valuable insights into the purpose of the example. Which problems come before it, after it, what numbers are selected, and what is said and not said—all reflect on the role of the exercise in the text.

What I want to focus on is the beginning of Ahmose’s text. It starts with the times-2 table for odd fractions and the division-by-10 table. Notice that there are no references to whole-number operations. From this we can infer that the students who used this book already knew whole-number multiplication and division. The initial focus on fraction operations, the basic tools required to work with fractions, suggests that this is in fact a fraction textbook. Much of the rest of the papyrus bears this out. After the tables, it begins with examples of fraction multiplication, followed by subtraction and division. The text then continues with word problems, most of which require fractions to solve. This is exactly the way most modern texts on fractions would be organized.

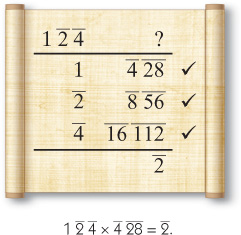

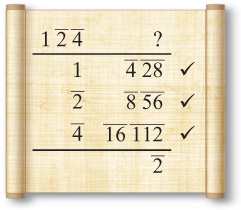

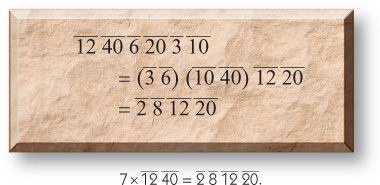

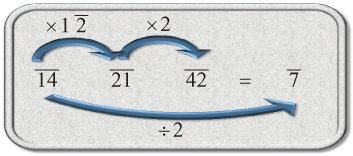

What comes at the start of Ahmose’s text tells us much about the fundamental ideas that will be utilized in the rest of the text. Let’s examine the first real problem in the papyrus, which appears immediately after the odd-fraction and division-by-10 tables in Ahmose’s text. It’s a multiplication of f sk by 1 s f. The computation itself goes like this.

The first thing we should notice is that constructing 1 s f on the left-hand side is trivial. This is made easy because the textbook writer doesn’t want us to focus on that aspect of the multiplication. Also notice that the calculation of each line is trivial. Taking half of f sk to get k gh is obvious to anyone familiar with the doubling of whole numbers. They know that twice 4 is 8, and their teacher makes it clear that this means half of f is k. Once again, this is not the focus of the problem, because it relies heavily on knowledge the student already has.

The only nontrivial part of this problem is on how the numbers in the right column, f sk, k gh, and ah aas, become s. Recall that I said that the book starts with the multiplication and subtraction and then the division of fractions. A sharp reader may have noticed that I left out addition. The simple truth is, this is not the first problem in multiplication, since it differs little from whole-number multiplication, but rather, it is the first problem in the addition of fractions.

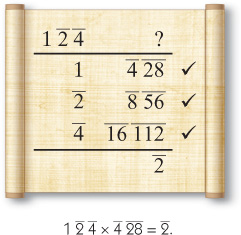

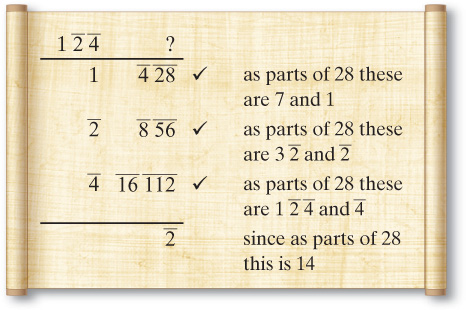

In the multiplication above, I left out an important part. There are comments to the side of the computation included below to explain how the addition was done. Here’s a more complete version of the previous multiplication. I’ll explain the added comments on the right shortly.

1 :2 :4 × :4 :2:8 with “parts” comments.

In order to understand what’s going on here, we need to go back to the pizza analogy we used to realize that s h is '. We could phrase this as follows. As parts of a six-slice pie, s is three slices and h is one slice. This is four slices, which as part of a pie, are expressed as '.

:2 + :6 = :3 as parts of a six-slice pizza.

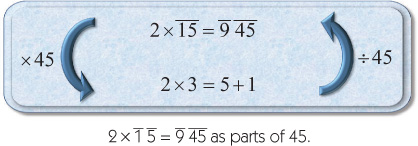

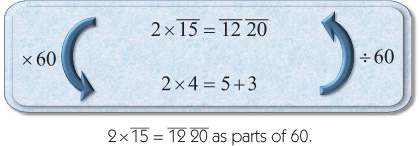

If we now phrase this in the same way as it appears in Ahmose’s text, it might appear as follows.

:2 :6 = :3 expressed in parts.

The problem from Ahmose’s papyrus uses parts of 28. Clearly sk of 28 is 1. Calculating f of 28 would be relatively easy for an Egyptian who would know that half of half of 28 is 7.

A fourth of a 28-slice Sicilian pizza is 7 slices.

I want to look at an easier example than the one Ahmose picked; one that doesn’t involve fractional parts. Consider the sum of s, d, f, and h. We can view these as parts of 12, since all of these numbers divide into 12 easily. Let’s think of these as fractions of a foot. Since half a foot is 6 inches, s is 6 as parts of 12. Similarly a third of a foot is 4 inches, a fourth is 3 inches, and a sixth is 2 inches. So we get:

s d f h feet = 6 + 4 + 3 + 2 inches = 15 inches

Our original problem was expressed in feet, and this means we need to convert our answer back into feet. I know 15 is 12 + 3, both of which can be easily expressed as parts of 12. As parts of 12, 12 and 3 are 1 and f, respectively. I can now finish my problem.

15 inches = 12 + 3 inches = 1 f feet

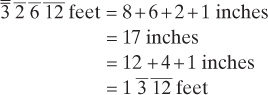

Hence, we now know that s d f h = 1 f. Here’s another example worked out using the inches-and-feet analogy. Remember that to an Egyptian, ' of a foot is obviously 8 inches, since 8 and its half is 12.

EXAMPLE: Use inches and feet to simplify ' s h as feet.

Notice that we could not break up the 17 inches into 12 + 5 because 5 cannot be made into a whole part of 12.

PRACTICE: Use inches and feet to simplify d f as feet.

ANSWER: ' feet

For the following problem, realize that a twentieth of a dollar is 5 pennies, a twenty-fifth is 4, and a fiftieth is 2. Realize that 10 pennies is a; of a dollar.

PRACTICE: Use dollars and pennies to simplify s; sg g; dollars.

ANSWER: a; a;;

The above method works well only because we are familiar with feet, inches, dollars, and pennies. I want to generalize this so we can work in parts of any size. We can only guess how the Egyptians worked with parts because we see only the finished result. Since our ignorance prohibits us from working these out as an Egyptian, I’m going to modernize the method. This will make the method easier at the expense of authenticity.

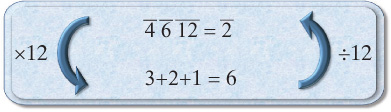

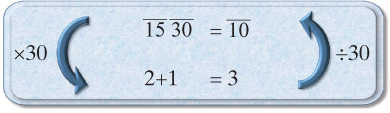

We need to understand that when we convert from feet to inches, all we’re doing is multiplying by 12. Similarly, when we go back into feet, we divide by 12. Consider the sum of f, h, and as. We can think of this as feet to be converted into inches by a multiplication of 12 as follows.

We’ve now computed that f h as as parts of 12 are 3 + 2 + 1, or 6. We can now convert back into feet by division by 12, giving s.

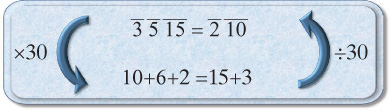

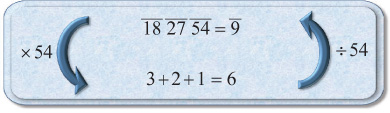

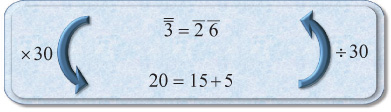

We can now do any problem. The only difficulty is finding a good way to break up a sum into easy parts of the multiplier. Below I’m going to work in parts of 30 and note that 18 can be broken into 15 and 3. Notice that we start with d, g, and ag and multiply by 30, putting our answer below the three fractions. Then we add the multiplied numbers and break them up into parts of 30, putting the answer on the bottom right. Finally we divide the parts by 30, putting our answer to the right of the equal sign. All of these problems have this U-shaped solution of “down, right, up.”

EXAMPLE: Add d, g, and ag as parts of 30.

SOLUTION:

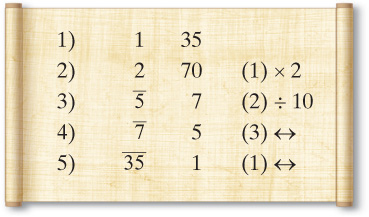

EXAMPLE: Add j, af, and sk as parts of 28.

SOLUTION:

Now try these.

PRACTICE: Add ', g, h, and d; as parts of 30.

ANSWER: 1 ag

PRACTICE: Add f, g, a;, and s; as parts of 20.

ANSWER: s a;

You might wonder where I get the number of parts for each problem. The answer is not easy, and I’ll elaborate on this choice later in the book. However, for now there is a relatively simple method for those familiar with the modern addition of fractions. Note that in the above problem, the parts f, g, a;, and s; all have nice, whole-numbered parts as part of 20 since 4, 5, 10, and 20 all go into 20 itself. This means that 20 is a common multiple of all the numbers that comprise the fractions. Since small numbers are generally easier to work with than large numbers, the least common multiple (LCM) is a nice number to use as the total number of parts. This is the same LCM that we used in grade school to find common denominators.

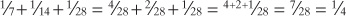

There is actually a close connection between our method of adding fractions and the Egyptian parts. Consider the following solution to the above problem where we added j, af, and sk to get f. The numbers were taken as parts of 28, giving 4 + 2 + 1, or 7, which is f of 28. If we add them as fractions in the modern way, the solution looks like this:

Note that 1/7 turned into 4/28. This is essentially saying that 1/7 as parts of 28 is 4. Also note the 4 + 2 + 1 over the 28. This is the same sum we did in the parts problem. Finally, when we reduced the fraction 7/28 to ¼, we essentially stated that ¼ is 7 parts of 28.

The methods are not exactly equivalent. We are familiar with LCMs from our method of adding fractions and our knowledge of the multiplication tables. An Egyptian would not find this as easy, but they had other methods. Consider the original problem Ahmose gave.

In order to solve this problem, Ahmose needed to add f, sk, k, gh, ah, and aas. The least common denominator is 112, which wouldn’t even be obvious to most modern math students. In fact, Ahmose doesn’t use 112, but rather 28. This may seem strange since it gives awkward answers. For example, as parts of 28, ah is 1 s f, something a seasoned mathematician would not see as trivial.

So why did Ahmose pick 28? The answer is remarkably simple. It’s easy to determine f and sk as parts of 28. They are 7 and 1, respectively. When he goes to figure out how many parts k and gh are, he simply notes that these are half of f and sk. This is obvious because he got these numbers by taking half of f and sk. So if f is 7 parts of 28, then k is half of 7 parts, or 3 s parts. Similarly ah is half of k so ah is half of 3 s parts, or equivalently, 1 s f.

This is easier than it looks. When going from one line of a multiplication to the next, the scribe performs the same operation on both columns. When he deals with parts, he simply applies the same operation to the parts. The beautiful aspect of this is that the Egyptian mathematician wouldn’t even pause momentarily to determine the number of parts, whereas a modern mathematician would have to contemplate for a while to determine a common multiple of f, sk, k, gh, ah, and aas.

Operations on the rows are the same for the parts.

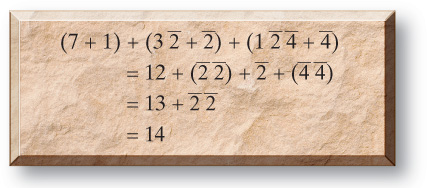

You might argue that the Egyptian method would generate fractions that would make the problem more difficult. While this is true, the fractions they obtain are the easiest fractions for an Egyptian to work with. All the fractions are powers of 2 and, as a result, simple to add. Consider the addition Ahmose did to obtain his total number of parts. Recall that f and sk were 7 and 1 parts of 28. Similarly k, gh, ah, and aas were 3 s, s, 1 s f, and f parts, respectively. When adding, you only need to know s s is 1, f f is s, k k is f, and so on. The numbers in the problem add up as follows:

So the total number of parts is 14. Remember what I said about the author of the text carefully selecting the numbers to make the method as transparent as possible? He wants his students to focus on the method, not on overly burdensome computations. As a result, this problem has the answer 14 parts. The author knows that his students can double in their sleep and would immediately be aware that 14 of 28 parts is s, the answer to the first exercise in the text.

“I have seen beatings.… I have witnessed a man seized for his labor.” So begins the advice of the renowned scribe Duau Khety to his son, Pepy. The warning is taking place as they sail up the Nile toward the Residence, the palace of the pharaoh. There Pepy is to be educated side by side with the sons of the foremost officials. Khety wants his son to take his studies seriously, so just like any other well-meaning father, Khety begins a long and serious lecture, which, assuming family life has changed little in the intervening millennia, would be completely ignored.

Khety spends very little of the lecture on the value of being a scribe. Rather, he warns Pepy of his fate should he fail. Khety describes the toil and hardship of the other professions of ancient Egypt one by one. He tells of the smiths whose fingers are worn as rough as the skin of a crocodile and who smell worse than fish eggs. He portrays craftsmen, bead makers, and bricklayers as overworked and whose arms are destroyed by the tiring labor. He describes reed cutters as laid low by mosquitoes and gnats. He compares potters to the buried dead, whose skin is constantly under a layer of mud. He warns his son of the oozing blisters on a gardener and the sores on fingers of the field laborers. He tells how carpenters can work a month on a roof and not be paid enough to feed their children. Khety relates how bird catchers and washermen live in constant fear of crocodiles and how the traders fear lions and barbarians. None of these professions, Khety tells his son Pepy, are free from abusive bosses. The one exception, of course, is the scribe, for he is the boss.

So learning to write is the only way to escape the horrors of life. As Khety puts it, a day in school “is more useful than an eternity of toil in the mountains.” He wants Pepy to “love writing more than his mother” and “recognize its beauty.” Khety ends his lecture by telling his son that no scribe ever goes hungry or even goes without the objects found in the house of a king. Pepy should be grateful for the opportunity he’s been given and to be sure to pass it on to his own children.

Scribes do seem to have lived a relatively easy life. Paintings often show them reclining under the shade of a tree, recording the occasional number as the workers toil in the hot Egyptian sun. A scribe didn’t go shirtless like the other workers, apparently because he was never forced to perform chores that would make him sweat. If we go by the idealistic portrayals on tomb walls, the scribes of Egypt did in fact have one of the easiest lives of the ancient world.

However, if you’ve ever worked an hour or more on a math problem without success, you might disagree. In the modern world, mathematics has a reputation for being anything but easy. Scribes needed to do math for their record keeping, easy or not.

As we’ve seen, in the previous section, adding fractions can be a bit tedious. First you’re confronted with a choice in number of parts, then you need to express all your fractions in those parts, and finally you need to break up your answer efficiently into numbers that have nice parts. Although this gets easier with experience, it would still take a while if you had to do this for every problem. Are there ways to sometimes take a shortcut and bypass this process?

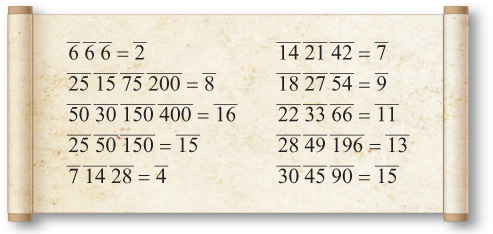

Consider the following simplifications of Egyptian fractions.

Each of these can be verified using the parts method. The number of parts needed is just the value of the second fraction on the left-hand side of each equation. For example, we can examine ag d; = a; as parts of 30. A fifteenth of 30 is 2, a thirtieth of 30 is 1, and a tenth of 30 is 3. So the equation becomes 2 + 1 = 3, which is, of course, true.

There’s a pattern in the above equations. It was noticed by Richard J. Gillings and described in his book Mathematics in the Time of the Pharaohs, which he “humbly” named the G rule.

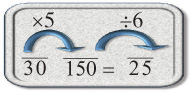

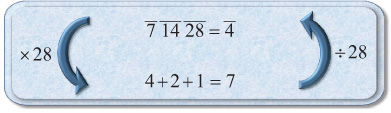

Consider the numbers by which you need to multiply or divide the successive terms of the equations to get the next term. In ag d; = a; we need to multiply 15 by 2 to get 30, and then we need to divide 30 by 3 to get 10. Similarly, for a; f; = k we need to multiply 10 by 4 to get 40 and then divide it by 5 to get 8.

Look at rest of the relations below and see if you can find the pattern.

Gillings noted that in each case the number you divide by is 1 more than the number you multiplied by. This trick always works when the numbers divide the quantity evenly. Assume we have the fractions d; ag;. The first thing you should notice is that we can get the 150 by multiplying the 30 by 5. At this point you should check to see if 1 more than 5 goes into 150 evenly. It does, since 150 ÷ 6 = 25. This tells us that d; ag; is, in fact, sg.

EXAMPLE: Simplify the following.

• f as

• dd dd;

SOLUTION:

PRACTICE: Simplify the following:

• as dh

• s; ak;

ANSWERS:

• l

• ak

What do we do if we get something like g ag? We can see that 15 is 5 × 3, but we don’t get a whole number when we divide 15 by 4. The answer is simple: don’t do anything. The number g ag is a perfectly legitimate solution in ancient Egypt. Likewise, when we see something like f l, where no whole number multiplied by 4 produces 9, we also generally do nothing.

At this point you might be skeptical as to the practicality of the G rule. If we picked two fractions at random, the chance that the G rule applied to them would be miniscule. What’s the point in knowing a shortcut that can rarely be used? What we need to know is that Egyptian fractions are not random numbers. Consider the following multiplication of 1 sf by 6.

Is it a coincidence that we ended up with two fractions, h and as, where one number is twice another? Of course it’s not, because we obtained h by taking half of 12. So it’s not a coincidence that 2 × 6 is 12. The only “coincidence” is that 12 is divisible by 3. Numbers divisible by 3 are hardly rare. If the last number were not divisible by 3, such as in the pair j af, the fraction could not have been simplified anyway.

Here’s another multiplication. On the papyrus, only the final simplified answer occurs. The simplification occurs below on the ostracon, a piece of broken pottery the Egyptians used for informal notes. I’ve placed number pairs about to be “G ruled” together in parentheses. Note the natural occurrence of double and quadruple numbers.

PRACTICE: Multiply and use the G rule to simplify your answer.

• 5 × s;

• 7 × sf

ANSWERS:

• f

• f sf or h k

A number of relationships we have already encountered are merely cases of the G rule. Recall that we have used d h = s, a simple example of the G rule. Also note that our rule for adding even fractions to themselves, like h h = d, is a fairly trivial case of the G rule.

In fact, it’s possible to show using modern algebra that any two Egyptian fractions that simplify to one fraction must obey the G rule. For example, the identity s h = ' doesn’t seem like the G rule until you realize that ' is aK.g and that 6 ÷ 4 is 1.5. Another example of a difficult-to-notice G rule is a; ag = h.

We can’t be sure the ancient Egyptians explicitly used the G rule. It may be that this is just an arithmetic relationship noticed by modern mathematicians who can easily spot such patterns; however, if it were something that obvious to an ancient Egyptian scholar, it’s likely that they recognized and used this mathematical tool.

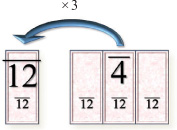

In fact, the G rule is completely obvious when seen in the right context. Consider the relationship h as = f. We can see that 2 × 6 is 12, so the answer is the fraction made by taking 12 and dividing by 3. Let’s think about what these multiplicative relationships tell us about the fractions. Remember that Egyptian fractions work in the opposite way as whole numbers do. The fact that the 12 is twice as big as the 6 tells us that h is twice as big as as. Interpret this literally. We can think of h as being composed of two ass. This relationship becomes clear when we think of the fractions as parts of 12, where the as becomes 1 and the h becomes 2.

h is composed of two ass.

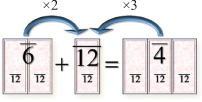

Similarly because 12 ÷ 4 is 3, we can think of d as being composed of four ass.

f is composed of three ass.

Now let’s interpret what the G rule says for this example. We start with h, which is two ass. We add one as to the two we already have. We’re told by the G rule that this is f, which is three ass. Summing up, the G rule says that two ass and one more is three ass, something anyone would find as obvious.

Two ass and one more is three ass.

In order to see the general pattern, let’s look at another example. Consider f as = d. When considering their relative size when compared to as, we see that f and d are three and four pieces of size as. So the G rule says that three ass and one more is four ass.

Three of something and one more is four.

When we apply the G rule, we must determine what you need to multiply the first term by to get the second term. This number represents how many pieces you start with. Adding the second term increases the total by 1. When we divide by one more, we’re merely acknowledging that we have one more piece. So the G rule essentially says that if you add one, then you have one more. Clearly, some ancient mathematician could have recognized this, and I’d be surprised if no one did.

It’s always an exciting day to find an ancient Egyptian scroll made of leather. The excessive cost of leather at the time meant that anything written on it was extremely important to its owner. You would expect something like a royal proclamation to appear on a roll of leather and not, as in the case of the Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll, a table of fraction identities.

As Gillings points out in his discussion on the leather roll, the Egyptians wrote on three main types of surfaces. The cheapest was ostraca, broken pieces of pottery and similar things. Pottery is made of mud, and mud was cheap in the river valley of the Nile. Clay pots were used to hold just about everything in Egypt. Wood, glass, and similar materials were just too rare or expensive. But pots get old, chip, and break, so there was no shortage of pottery shards. Although few people could write, the middle class had to keep some records. These were generally written on economical ostraca.

The next class of writing surface was papyrus. The name comes from a plant once found in the marshes of Egypt. It was so important in the ancient world that our modern word “paper” derives from it. To make a sheet of papyrus, someone went to the mosquito-infested swamps to gather the plant. The long thin leaves were then laid out side by side. On top of this, another layer was laid perpendicular to the first layer. The two layers were then beaten until the juice of the plant came out of the leaves. The liquid acted like a glue to hold the leaves together. The sheets formed could then be joined end to end and pounded together to make long strips of paper for use in a scroll. After the leaves dried out, the writing surface was smoothed by sanding it down. Although papyrus itself probably wasn’t expensive, the untold hours required to make a single sheet of paper meant it was only used for important purposes, such as an official record or textbook.

Yet papyrus wasn’t the most expensive writing material; leather was. The scarcity of leather was a direct consequence of the scarcity of meat, which in the ancient world was a luxury. It’s only in the latter half of the twentieth century that meat became a substantial portion of the diet, and even then only in the most prosperous countries. Cows and other livestock consume a lot of food, and a number of families can be fed on the amount of grain it takes to make enough meat for one person. In the ancient world where food was relatively scarce, arable land couldn’t be wasted for animal feed. Hence, livestock were generally confined to grazing on areas unsuitable for farming, so there wasn’t a lot of meat.

People still ate some meat since protein is an important part of the diet. But for commoners it was reserved for special occasions like religious festivals. Since few cows were slaughtered for food, there simply wasn’t that much leather, and the resulting scarcity made it extremely expensive. So if leather was so costly, why would anyone use it for a math table? The answer is, because they could.

We can imagine a suave scribe strutting through some ancient Egyptian town in his fine linen clothes. He would then discreetly adjust his shirt so his pot belly would just barely show. In the ancient world where wages were paid in food, doing so would be the equivalent of flashing a platinum-class credit card. When he caught the eyes of some attractive young impressionable girl, he would pause, pretending to be thinking about some math problem required by his high-powered career. Slowly he would pull out his math table from under his arm. The girl would undoubtedly swoon as she eyed the leather scroll worth more than all the objects in her father’s house combined. He gives her a wink and thinks to himself that life is good.

As ridiculous as the above description may sound, it’s essentially correct. The use of leather for the scroll was probably more of an indicator of social status than of serving some practical value. It is interesting that some scribe used a mathematical table as symbol of class, much in the same way as a modern CEO might wear an expensive watch. If the practice of using leather for mathematical tables was widespread, it would suggest that the scribes of Egypt had wealth and social standing. If nothing else, the existence of the leather scroll demonstrates that mathematics was greatly respected in the ancient world.

I’ve tried to loosely mimic the use of ostraca, papyrus, and leather in the backgrounds of the computations in this book. Most of the examples are done on the image of a papyrus scroll. You can tell if a scroll is papyrus by looking carefully at the texture in the image. You should be able to see subtle lines going vertically and horizontally. This is a vestige of the reeds that were placed down in these directions in the manufacture of the papyrus. For tables, I’ve used a leather scroll background. You can spot these by the lack of lines in the texture and the thicker scroll rolls. For “scratch work,” I’ve often used an ostraca background. And occasionally, I’ve used a “modern” looking background for operations not done in a traditional Egyptian style, such as when we compute parts through multiplication.

On the Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll there are dozens of fraction identities. Many of these are examples of the G rule discussed earlier. For example, the relation a; f; = k appears near the beginning. You might be wondering that if the Egyptians knew the G rule, why would they need this table? Couldn’t they just see that 40 is 4 times as large as 10 and then divide 40 by 5? I can give a couple of possible explanations.

G-rule expressions in the Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll.

It’s relatively easy for us to simplify a; f; because at some point in our lives, we were forced to memorize 4 × 10 = 40 and 5 × 8 = 40. The Egyptians performed their math through doubling and so never needed to learn multiplication tables. As a result, these relationships wouldn’t be immediately obvious. Hence the table might serve the same purpose as our memory when we apply the G rule.

We also need to know that the leather roll has only some twenty-odd relations. It obviously is not meant to serve as a complete fraction simplification guide; its purpose might be to simply show examples. By examining these equations, perhaps students were meant to obtain some general rules. The relation after a; f; = k is followed by g s; = f. Perhaps they were intended to note the “× 4, ÷ 5” relation embedded in the two equations. Or perhaps the equations were intended to show that you could take a known relation like a; f; = k and divide it by 2 in order to obtain a new relation like g s; = f.

Non-G-rule relations on the Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll.

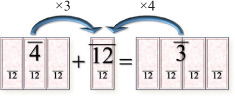

The Egyptian Mathematical Leather Roll had many equalities that do not satisfy the G rule. One of the identities on the scroll is j af sk = f.

:7 :1:4 :2:8 = :4 verified as parts of 28.

We can easily verify this relationship by considering parts of 28. In this system the identity becomes the obvious identity 4 + 2 + 1 = 7.

This identity would be useful only for adding terms with a j, a af, and a sk. For randomly selected numbers, this would almost never happen. But as I discussed when considering the G rule, Egyptian fractions are not random. The methods involved in their use cause certain “coincidences” to happen repeatedly. Consider the following multiplication of j by 3 s.

The answer is awful. We could simplify it as parts of 28. However, we now know the identity f = j af sk, found above, and we can see the three terms of the right-hand side within our answer. So we can simplify it as follows.

Notice how this identity seems ready-made for my multiplication of j. Try these multiplications and focus on the “coincidences” that occur. You need to be careful because these can be simplified in a number of ways. To get the answer given, be sure to use the j af sk = f identity as soon as you see it. Also be sure to put the j term in the right column.

PRACTICE: Multiply then simplify using j af sk = f

• 5 × j sk

• 5 f × j

ANSWERS:

• s f j

• s f

Now let’s look at another identity on the leather roll, ak sj gf = l. We can verify it using parts of 54 as follows.

:1:8 :2:7 :5:4 = :9 verified as parts of 54.

We can also confirm this identity as two applications of the G rule.

1:8 :2:7 :5:4 = :9 verified using the G rule.

Consider the multiplication of gf by 6. Once again “coincidences” happen.

Notice that with the table, the answer immediately simplifies to l. Also notice that while regular doubling gave us the sj from the gf, Ahmose’s double-fraction table gave us the ak we needed for our identity. It should hardly come as a surprise that the pieces of Egyptian mathematics are meant to come together as a cohesive system. In the practice multiplication below, there are a number of ways it can be solved. To get an answer that matches the one given, reduce the ak sj gf first.

PRACTICE: Multiply then simplify using ak sj gf = l

• dh gf × 6

ANSWER: h l

We need to be careful when dealing with ancient mathematics. Just because we find a possible use of some ancient mathematics doesn’t mean that’s exactly how it was used in the past. We’ve been using the relations of the leather roll literally. Perhaps they were used in a more abstract way. Consider the relation af sa fs = j. Ancient scribes may have viewed the terms on the left side proportionally, as we do when applying the G rule. They would probably have recognized that 21 is 14 and its half, 7, from their knowledge of multiplication by '. And they would have also immediately recognized that 42 is double 21. The relation could have been interpreted to mean that the solution is half of the initial term.

:1:4 :2:1 :4:2 = :7 in relative terms.

Notice that the next term on the leather roll is in fact the same relationship. Note that in the equation ak sj gf = l, 27 is 18 and its half (9), and 54 is twice 27. Applying the same rule the solution should be generated by taking half of 18 and in fact the answer is l.

EXAMPLE: Simplify s; d; h;.

SOLUTION: Since 20 × 1 s = 30 and 30 × 2 is 60, s; d; h; = s; K÷s = a;.

PRACTICE: Simplify as ak dh.

ANSWER: h

Although the night watchman was paid in bread and beer, most professional Egyptians were paid primarily in grain. Workmen in the Valley of the Kings were paid over 500 pounds in wheat and barley each month. This is estimated to have easily fed ten people. This means that the typical Egyptian household had to be by and large self-sufficient in terms of production. They had to grind their own flour and bake their own bread. They used the barley to brew their own beer. They even had to spin their own thread out of flax and weave their own linen.

As we’ve seen, the people of ancient Egypt were in many ways self-reliant, making what they needed for themselves. Is it possible that Egyptian mathematicians regularly made their own tools? Ahmose’s papyrus has a table for doubling odd fractions and a table for division by 10, and the Mathematical Leather Roll is a table of fractional equalities. There’s no doubt the Egyptians used these, but we are confronted with the questions of how they found them and whether, if they needed expressions not found on one of the tables, they could have created them on their own.

The simple truth is that, creating Egyptian style fraction equalities is trivial, especially if we think in parts. Let’s start with a number with a lot of factors, 30. The factors are 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 10, 15, 20, and 30. The modern perspective would not consider 20 to be a factor of 30, but just as 5 is h of 30, thus making it a factor, 20 is ' of 30. These whole numbers can be associated with fractions when thinking of them as parts of 30. Hence 2 is ag of 30 and 6 is g of 30. A scribe could easily make a table deriving all of the whole parts of 30 as follows:

The whole parts of 30.

Now pick any number in the third column of the table, say 20, and write it as the sum of other numbers on the table. For example, consider 20 = 15 + 5. We can now write the fractional equivalents, ' = s + h, giving us an identity. We could express this with arithmetic in the following way:

Each equation we make from the whole numbers from the above table gives us a new identity. To solve the following problem, we first convert the fractions into their corresponding parts: 10, 6, and 2. Then we add them and try to express them in numbers from the table.

EXAMPLE: Make an identity for the simplification of d g ag.

PRACTICE: Make an identity for the simplification of g a; d;.

ANSWER: d

We can use this method to find sums of fractions equal to a particular fraction. For example, if we want to find ways to add fractions to get to ', we simply try to add numbers from the table to get to 20. We’ve already seen that 15 + 5 = 20 generates the identity s h = '. Similarly 15 + 3 + 2, 10 + 6 + 3 + 1, and 10 + 5 + 3 + 2 generate s a; ag, d g a; d;, and d h a; ag, respectively, all of which equal '.

PRACTICE: Using the whole parts of 30, find all identities that sum to d.

ANSWERS: g a; d; and h a; ag

We can now see how the division-by-10 table in Ahmose’s papyrus may have been constructed. Recall that the table had values for the numbers 1 to 9 all divided by 10. As parts of 30, the fractions 1/10, 2/10, and 3/10 become 3, 6, and 9, respectively. It’s not hard to see that each number is 3 times the number that gets divided by 10. Hence as parts of 30, 7 ÷ 10 becomes 7 × 3, or 21. We can think of this as 7 × a;, and the a; then converts into a 3. Using the value of 7 × 3, we can now write 21 as 20 + 1, which when converted back into fractions is ' d;. This is precisely the entry that appears in the table.

EXAMPLE: Using the whole parts of 30, find an expression for 4 ÷ 10.

SOLUTION:

PRACTICE: Using the whole parts of 30, find an expression for 3 ÷ 10 and 8 ÷ 10.

ANSWERS: g a; and ' a; d;

All the answers we’ve obtained above are the values in the table. This suggests that the division-by-10 table may have been constructed in a similar manner.

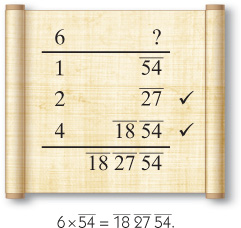

If we now choose a number different from 30, we can create a new table of parts. Consider the following table containing the whole parts of 28.

The whole parts of 28.

From this table we can notice that 7 = 4 + 2 + 1 means f = j af sk and similarly form other identities. We could also create a table for the numbers from 1 to 6 when divided by 7. For example 3 ÷ 7 could be determined as follows.

The change from 30 to 28 has some effect on the types of identities we can create. As we see above, we can form expressions with j in them because 7 is a factor of 28. However, we lose the ability to express d and ' because 3 is not a factor of 28, although it is one of 30. The loss of ' is particularly troublesome for the expression of large fractions. It’s difficult to add whole parts of 28 to numbers like 27. In fact, there is only one way to do it: 14 + 7 + 4 + 2, which makes the particularly ugly fraction s f j af. The initial fraction s is a lousy approximation to this number, which is much closer to ', but because ' doesn’t form a whole part of 28, we can’t easily use it. Since there is often only one way to add the whole parts of 28 to get certain numbers, the number of identities we can find is limited.

The problem would get even worse if we picked a number like 35. The whole parts—1, 5, 7 and 35, given below—will only sum up to a handful of numbers. For example, we can’t get any of the numbers from 2 to 4 or any from 14 to 34.

The whole parts of 35.

The difference between 30 and 35 is due to their prime factorizations. When completely factored, 30 is 2 × 3 × 5, while 35 is 5 × 7. The number of factors and their size determines how many whole parts a number will have. The first number has three prime factors and the second only has two. This means 30 will have more parts than 35. Since you need more, smaller numbers to multiply to a large number, the smaller the factors, the more parts. The number 28 is 2 × 2 × 7. Although it has three factors, the repeated 2 reduces the number of parts slightly. In general, for the number of parts to be useful, you want it to be the product of many small, different factors.

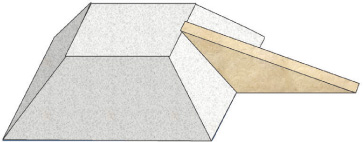

Ancient history consists of a few scattered remains that force speculation to complete it and create a cohesive story. We’re often confronted with two or more choices with little to go on except common sense and intuition. A good example of this is in the construction of the pyramids. No one is quite sure how they were built. The stones used were often massive, but they somehow were lifted to the top of what were the tallest man-made structures until the construction of the Eiffel Tower.

It’s assumed the Egyptians used a ramp, because the slopes of the pyramids were too steep to safely push the massive stones up the sides safely. The question considered is, what form did these ramps take? The simplest answer is that perhaps they were straight.

A partially built pyramid with a straight ramp.

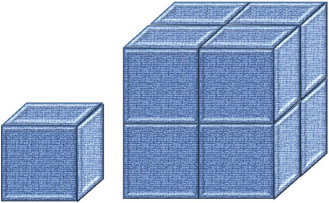

There’s a problem with this solution. The ramps would get large quickly as the pyramids got bigger. Assuming the ramps had a uniform width, doubling the height of a ramp would quadruple the amount of material required to build it. This is easily seen with an example. Consider the triangles pictured below. The triangle twice as large in length is composed of four of the smaller triangles.

A triangle twice as high is made of four smaller ones.

This is called quadratic growth. The size grows with the square of the length. So if you double the length, you multiply the size by 22, or 4. Similarly if you triple the length the size grows by 32, which is 9 times larger. This relation is easiest to see on the growth of square. If you take a square, you need three rows of three to make a new square 3 times larger. Clearly, three by three is 3 × 3, or 32. As the pyramid grows, the size grows rapidly. If the size goes up 20 times, the size of the ramp grows 400 times, and so on.

Three times as long requires three by three.

So some have suggested that the ramps got too large for the Egyptians to have used this method. Instead they suggest that the ramps spiraled around the pyramids.

A partially built pyramid with a spiral ramp.

Both the width and height of the ramp remain fixed since it only needed to extend to the pyramid, not the ground. Hence the growth in the size of the ramp is linear. This means that if it gets twice as long, the ramp volume grows by two as well.

There’s a problem with this method. The analysis assumes that the only consideration is the quantity of material required to make the ramp. There are many others. For example, which ramps are structurally sound? Remember that pyramids with seked of 5 or less eventually collapse. Similar physics holds for ramps.

We also need to consider how the shape of the ramp affects its efficiency. Image how difficult it must be to turn a stone block that weighs 2 s tons. If we assume that the block is being pushed on rollers, they need to be turned along with the block. However, they’re under thousands of pounds of stone. Hence the straight ramp may be ultimately more efficient even though it takes more work to build.

This problem gets worse when you realize that the size of the pyramid grows cubicly. In other words, when you double the height of the pyramid, the number of blocks you need grows by a factor of 8. When you need to move millions of blocks, 8 times as many difficult turns is nothing to ignore. It’s not hard to imagine that a bigger ramp would require far less work. The cubic relation means that you cube the growth in length to get the growth in volume. So 5 times larger means 53, which is 5 × 5 × 5, or 125, times as large. This is easily seen in terms of a cube. The following diagram shows that to make a cube twice as large, you need eight—2 × 2 × 2—blocks.

A block twice as large is made of eight smaller blocks.

When considering how the Egyptians created identities we also are confronted by two competing theories, neither of which can be proved or disproved. In the previous section we more or less accepted the point of view that the Egyptians started off with a set number of parts and from that generated identities. We are now going to speculate on methodologies that start with the fractions themselves rather than with the parts.

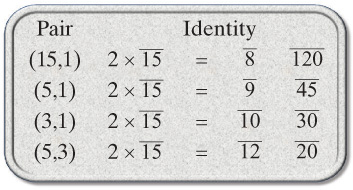

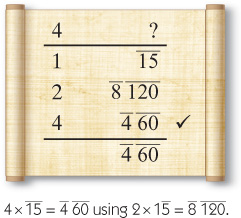

Consider the identities of Ahmose’s table for multiplying odd numbers by two. In that table we see entries such as 2 × j = f sk. Notice the 4, 7, and 28 are all whole parts of the 28 mentioned in the last section. We can view this identity in the same way as when we created the division-by-10 table, thinking of this as 2 ÷ 7. Since j is four parts of 28, 2 × j is eight parts of 28. Since 8 = 7 + 1, all of which are whole parts of 28, we know that 2 × j = f sk. We can represent this algebraically as follows:

This trick always obtains the table entry if you pick the “appropriate” number of parts. However, the choice of the number of parts is not always obvious. There are rules of thumb to use when selecting the parts. One obvious rule is that you want the initial fraction to be a whole number of parts, so since we started with j, we would want the number of parts to be a multiple of 7.

Instead of selecting the number of parts, I’m going to show you a method that selects the number of parts for you, and it works well for generating two term identities. Let’s find an identity for 2 × ag. Pick any two factors of 15. I’m going to pick 5 and 1. Now put them in the bottom right of our parts computation as shown and also put the 2 × ag on the top left.

We know 5 + 1 is 6 and 6 is 2 × 3, so we can put 2 × 3 on the bottom left.

Now we need to think backward. The ag corresponds to the 3, so a fifteenth of some number of parts is 3. What number of parts is this? We know a fifteenth of 15 is 1, a fifteenth of 30 is 2, so a fifteenth of 45 is 3. Hence there are 45 parts. The 45 is just 3 fifteens so we could have obtained this solution by multiplying 3 × 15. Now that we know the number of parts is 45, we can determine what fractions the 5 and the 1 correspond to. When divided by 45, these become l and fg, respectively. Hence we get the following final answer:

We chose the factors 5 and 1, but this method still works if we choose any two factors of 15. Let’s now try 5 and 3.

EXAMPLE: Find an expression for 2 × ag using the factors 5 and 3.

Start with 2 × ag on the top left and put our two factors, 5 and 3, as a sum on the bottom right. We know 5 + 3 is 8, which is 2 × 4. So 2 × 4 goes on the bottom left. We now calculate the number of parts ag would be of 4, which is 15 × 4, or 60. Finally we determine what fractions 5 and 3 are of 60. We do the divisions 5 ÷ 60 = as and 3 ÷ 60 = s; and put these as our final answer on the top right. We now know 2 × ag = as s;.

SOLUTION:

PRACTICE: Find an expression for 2 × ag using the factors 3 and 1.

ANSWER: a; d;

Notice that we’ve finally found the entry on Ahmose’s table. Before we finish with finding expressions for 2 × ag, try creating one using the factors 15 and 5. You will see that we get the same answer as using 3 and 1. This is because 3 and 1 can be scaled to 15 and 5 by multiplying by 5. In general we can ignore factor pairs that have common factors since they produce the same solutions as simpler pairs.

PRACTICE: Find an expression for 2 × ag using the factors 15 and 5.

ANSWER: a; d;

The battle between the two strongest gods, Horus and Seth, disrupted the heavens and the earth. The moon itself was destroyed in the conflict. The gods had to put an end to the violence and hence formed a tribunal to settle the dispute peaceably and decide which of the two would become the king of the gods.

It had all started many years ago when the god Osiris ruled the land of Egypt. At the time he was the god of the Nile valley and embodied the fertility of the land. His skin was the green of the vegetation that flourished in his domain. Osiris was a good king, and Egypt prospered under his dominion.

Osiris, lord of the underworld.

Seth, god of chaos.

Seth, the brother of Osiris, was the god of the red desert. He embodied the destructive power of the harsh lands that surrounded Egypt. As a result, he was the fiercest warrior of the gods and was greatly feared. Seth was also a jealous god who watched his passive brother control all the glory of Egypt.

Seth devised a plan. He threw a party and invited the unwitting Osiris. At the end he brought out a coffin he had made especially to fit Osiris. Seth announced that whoever fits perfectly into the coffin will win a prize. One by one the guests tried it out but no one fit exactly until Osiris. At this point Seth and the other guests, who were in on the conspiracy, shut the lid, nailed it down, sealed it with lead, and threw the coffin in the Nile.

Isis, the wife of Osiris, found the body and revived it long enough to conceive a son, Horus. Ma’at, the goddess of order, declared that the dead Osiris could not remain in the land of the living, so he descended into the underworld to become its ruler. As Horus grew up, Seth repeatedly tried to kill the boy, but Horus was hidden in the papyrus plants and protected by many powerful gods.

When Horus reached manhood, he set out to avenge his father. When he found Seth, the two battled. Horus’s left eye (the moon) was ripped out and torn to pieces. Seth lost a body part of his own. Let’s just say that my male readers will agree that Horus won because he lost only an eye. However, the fight proved inconclusive. Thoth, the god of wisdom, found the pieces of the moon and repaired it. Horus gave the moon to his father, Osiris, and Seth healed as well.

Horus, the son of Osiris.

Before they could battle anew, the gods formed a tribunal to mediate the dispute. It consisted of the Ennead, a group of nine gods, and was led by Ra, the sun god. Most of the Ennead seemed to favor Horus’s claim, but Ra, one of the oldest and most venerable of the gods and also the sun god, sided with Seth. The tribunal repeatedly sent letters to the elder gods seeking advice. The first letter was sent to Neith, mother of all things. She sent a reply that justice should be done and the rightful heir should take the throne. This did nothing but enrage the sun god, who declared that the kingship was too much for someone so young.

Letters were exchanged between Atum, the god of the beginning and end of time, and Osiris, both of whom supported Horus. Each time, Seth flew into a rage and challenged Horus to some competition to decide the matter. Horus won, often with the aid of his mother, who used trickery to offset Seth’s brute force. After eighty years, Atum ordered that Seth be placed in shackles and awarded the crown to Horus.

On the surface, the above tale might seem a simplistic story of good triumphing over evil. Although the Egyptians did have a strong sense of right and wrong, they were not so shallow. Ra was not wrong for supporting Seth. Seth was needed each day to protect the sun from destruction. But neither was Seth entirely evil. Isis tricked Seth by magically disguising herself. She related a tale wherein her son was robbed of his deceased father’s cattle by a stranger, to which Seth replied that the stranger should be beaten in the face with a rod so that justice could be done. Isis at this point revealed her true form to Seth and he became ashamed by his own actions. Although Seth didn’t withdraw his claim, he himself reported the incident to the tribunal so he could be judged.

On the other hand, we also can’t assume that Horus was purely good. He was driven by anger and the desire for revenge. When his mother showed Seth some mercy, Horus became enraged and struck off her head. While the act was not lethal to a goddess, it was still considered a great offense, and it was Seth who sought out Horus in order to punish him.

The wisest voices did not seek a victor in the conflict but, rather, reconciliation. They knew that strength was needed as well as fertility and justice. The end of the story is telling. After it was decided that Horus should be made king, the most ancient god, Atum, asked Seth why he even allowed himself to be judged when he could just have used force to take the crown for himself. Seth simply replied that they should give the kingship to Horus. For his acquiescence, Seth was taken to the heavens, where he roamed the sky as thunder.

As with Seth and Horus, when judging what is best, even in mathematics you can’t be too simplistic. As we’ve seen, Ahmose had many choices for the value of twice a fraction such as 2 × ag. Let’s consider all the two-term identities. These can be generated by considering factor pairs of 15.

All possible two-term identities for 2 × :1:5.

The original author of Ahmose’s papyrus needed one identity for his table but had at least four reasonable identities to choose from. Although we can’t be sure why he selected the identities found at the beginning of the scroll, we can look at his choices and try to backward engineer the process through which they were selected. Below are four criteria he seems to have used, and you will see why they are very practical.

1. Good Approximation

When we first examined Egyptian fractions, I pointed out that we can think of the multiple fractions as approximations that get refined with each term. For example we can think of k as; as roughly an eighth. It differs from one-eighth by a hundred and twentieth. Since 120 is much larger than 8, the error is extremely small and the approximation of the value being an eighth is quite good.

The fraction as s; offers a lousy approximation. The expression makes the claim that the value is roughly a twelfth, but the error, a twentieth, is fairly large compared to a twelfth. Half of as is sf, which is smaller than the error of s;, so we’re off by more than half. This is far too large for as to be a good approximation.

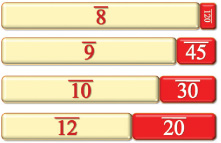

Below is a visual representation of the four approximations. The length of each bar represents 2 × ag. The light bar on the left of each represents the first fraction. This can be thought of as the approximation. The closer it is to the length of the whole bar, the better the approximation. The dark bar to the right is the error represented by the second fraction. The smaller the error, the better the approximation.

It’s easy to see that k is the best approximation in the lot. If this were the only criterion, that’s what we would select. However, there’s more. At this point let’s eliminate as s; from contention because it is such a bad approximation.

The approximations of 2 × :1:5.

2. Even Fractions

Egyptians had to double fractions constantly in their computations. When they had to double odd fractions like ag, they had to consult a table or their memory. Imagine the frustration of Egyptian students multiplying ag by 4. In the very first step they would need to consult a table to determine the value of 2 × ag. If the table used the value l fg, the problem of odd fractions would rear its ugly head once again. The student would have to do two look-ups: one for l and one for fg. The result would be an untidy collection of four fractions. While they could be reduced to two fractions using the G rule, it’s still more work than a simple multiplication should entail.

On the other hand, if the table had the value k as; or a; d;, the problem of odd fractions would go away, and the next doubling would be trivial. There would also only be two fractions on the third line, eliminating the need to simplify the expression.

Out of the fifty entries in Ahmose’s table, only six start with odd fractions. Two of the six, d and ', are easy to double. The Egyptians clearly know that the table should contain as many even fractions as possible, and anyone who has spent any time multiplying the Egyptians’ way knows this, too. So, we will ignore the possibility that 2 × ag = l fg.

3. Avoid Large Numbers

Which numbers would you rather multiply: 7 × 5 or 83249 × 2734? If you’re like most humans, you won’t need me to explain why Egyptians didn’t like large numbers, but let me give you a few other reasons that might not be immediately obvious. The first thing we must remember is that their table only doubles odd fractions from d to a;a. If they needed to double a;d, they would have had a slight problem.

There’s also the concern about fair division. Recall how we first examined Egyptian fractions by slicing loaves of bread. If we wanted to split up two loaves of bread between 15 workers, each would get 2 × ag. We have only two solutions left to consider, a; d; and k as;. For the first, we would cut the two loaves into tenths. This would make 20 slices, of which we would then hand out 15, one to each worker, leaving 5.

Two loaves cut in tenths with 15 slices handed out.

We would then cut each of the remaining 5 in thirds, giving us 15 smaller slices, exactly one for each. Since these slices are a third of a tenth, they have size d;, so each worker received a; d;.

The five remaining are cut in thirds and handed out.

Let’s see what would happen if we tried to do this with the answer k as;. Initially there is no problem. We cut each loaf in 8 pieces, making a total of 16. Of these we hand out 15, one to each worker.

Two loaves cut in tenths with 15 slices handed out.

The one slice that remains is then cut in 15 slices. A fifteenth of an eighth is one-twentieth. These “slices” are nothing but crumbs, having been cut far too thin. In fact, the one slice would probably be too thin to cut easily. The workers would gladly accept the k-size slice but would scoff at their second piece. As a practical matter, physical items cut in size as; are just not workable.

The last slice, cut in 15 parts, is too small.

So, as we have seen, large numbers are difficult to work with both in fractions and in the physical world. Hence it would be natural for the Egyptians to avoid expressions like k as;. After we eliminate this choice, we are only left with the value of a; d; for 2 × ag. Perhaps it should come as no surprise that this is precisely the entry that the author of Ahmose’s papyrus selected.

4. As Few Fractions As Possible

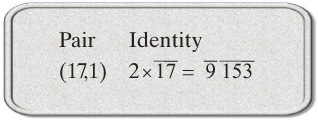

When we considered 2 × ag above, we obtained a number of two-fraction expressions from which to choose. However when we consider 2 × aj, we’re not so lucky. This is because 17 is prime: it only has two factors, 1 and itself. If we were to limit ourselves to the factor method of generating identities, then we would only get the following equation.

The following expression is wrong in oh so many ways. Both terms are odd and 153 is too large. Even worse, when we would have to double agd, we would be out of luck since our table goes only to a;a. The Egyptians realized that it’s better, in general, to work with as few fractions as possible—but there are exceptions. For this problem they chose the identity 2 × aj = as ga hk. It’s a decent approximation: all the numbers are relatively small and two of the three are even. It’s not difficult to see why they might have selected this identity over the only two-term expression l agd.

There is only one two-term identity for 2 × :1:7.

When I use the above four criteria to rate fractional identities, I frequently choose exactly the same entries that appear on Ahmose’s table. For most of the ones with which I differ, I can still see why the other value was selected. However, there are a few whose values seem poorly chosen. At this point we have to realize that it’s all but impossible to understand exactly how the Egyptians viewed these identities and the criteria by which they selected them. In the end, we must accept that this is all speculation. When we encounter something that does not precisely fit our theories, we’re forced to keep an open mind.

Years ago I was told the following anecdote about Paul Erdös, arguably the greatest mathematician in the last half century. While still a student, he demonstrated a solution to a problem using what would later be called the probabilistic method. By viewing certain mathematical structures as the outcome of random choices, he was able to assign probabilities to them and use these values to answer questions.

The ideas he considered were often trivial. Consider rolling two dice. You’re told that the probability of rolling a 13 is 0. This tells you that it is impossible to do. On the other hand, if you’re told the probability of rolling a 10 is 1 in 12, then you know there must be a way of rolling a 10. This is mathematically certain even if you don’t know anything about dice. This is because 1/12 is greater than 0. Erdös also used the notion that if two events are likely to happen, then it must be possible for them to happen at the same time. For example, I am almost certain to roll more than a 3. I am also almost certain not to roll an 11. I can now conclude that there must be a way to roll a number more than 3 that’s not 11. All you need to know to prove this is that the probability of each is more than half. Intuitively this is trivial. If we’ve both read more than half the articles of a magazine, then some article must have been read by both of us. Erdös’s ideas were simple but their use was inspired.

Upon hearing of the method, an elder mathematician declared that it was pointless. He realized that every problem that could be solved with the probabilistic method could be solved by combinatorial methods, that is, mathematical methods that count complex objects. It’s essentially the difference between saying “I have 3 of 4” and “There is a ¾ths chance that any one of them is mine.” The reason there is a probability of 5/18 of rolling a 9 is that there are 10 ways out of 36 of obtaining this number. The fact that the 10 is not 0 means there is a way to roll a 9.

On the surface, the grumpy mathematician was right. In some logical sense, the two methods are redundant. Yet after a few years, the probabilistic method was used to answer many problems that had remained unsolved by people using combinatorial methods. What the objecting professor missed was that how you view things changes how you think about them. Mathematicians think about probabilities in different ways than we visualize quantities. Erdös didn’t change the math; the numbers in essence stayed the same. Rather, he changed our conception of the numbers. New thoughts meant new ideas, which in turn meant new solutions.

The way we do mathematics today is radically different than the way it was done for most of human history. Everything is thought of in terms of algebra. Open any undergraduate or graduate text and you will see lines and lines of algebra, even if the subject has nothing to do with numbers. Human reasoning itself has been reduced to algebra. Consider the following expression (don’t worry if you don’t understand it):

∀(a, b)∊S2, (a→b) →(~b→~a)

What if I were to tell you the above symbols are obvious? We know that if it is raining, then the ground is wet. If you noticed the ground was not wet, what would you conclude? Hopefully you would realize that it’s not raining. That’s essentially what the above expression says. The idea embodied in the above expression is simple. Realizing that it is simple is the hard part.

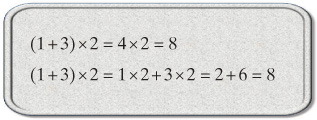

The distributive law can be represented algebraically as (a + b)c = ac + bc. When I get an expression like (1 + 3) × 2, the parenthesis tell me to add the 1 and 3 first giving 4 × 2, which in turn is 8. However the distributive law says we can multiply the 2 by the individual numbers first, getting 1 × 2 and 3 × 2, or equivalently, 2 and 6. Then we can add them to get 8. How did we know we would get the same answer? The distributive law promised us we would.

The two ways produce the same solution.

As a mathematician, I feel compelled to prove anything I state. So how do I prove the distributive law? The simple truth is I can’t. A law in mathematics is something that can’t be proven. Often called axioms, these statements are fundamental truths that must be accepted on faith.

Open a copy of Euclid’s Elements, a textbook that’s more than two thousand years old, and you will find a proof of the distributive law. How could they have proved something that has no proof? The simple answer is that they didn’t look at it the way we do. What we assume, what we require justification for, and the methods we accept as valid are shaped by our view that math is algebra. Take, for example, how the Greeks looked at math in terms of geometry.

Let’s now try to view the distributive law from the Greek perspective. In geometry there are only lines and shapes. There is no multiplication. So how can we express 3 × 2 in geometry? Recall that the area of a rectangle is the product of the base and the height. We can think of 3 × 2 as the area of a rectangle with a base of 3 and a height of 2.

3 × 2 is just a 3-by-2 rectangle.

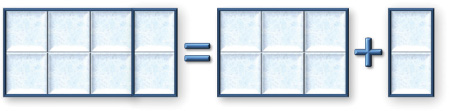

Now the distributive law tells us that (3 + 1) × 2 is the same as (3 × 2) + (1 × 2). Thinking in terms of rectangles, (3 + 1) × 2 is just a 4-by-2 rectangle where the 4 is viewed as the combination of a piece of 3 and 1. The sum (3 × 2) + (1 × 2) is just two rectangles, a 3-by-2 and a 1-by-2, combined. So the theorem says that the big rectangle, (3 + 1) by 2, has the same area as the two small rectangles 3 by 2 and 1 by 2. Look at the diagram below. It shows that the large rectangle has simply been cut in two pieces and that the area of the whole is just the sum of the pieces it has been divided into.

(3 + 1)×2 = (3×2) + (1×2) expressed geometrically.

So to a Greek, the distributive law simply says that if you combine two rectangles of the same height, you don’t change the area. The area of the pieces is the same as the area of the whole. In fact, this is the axiom the Greeks used: a whole is the sum of its parts. When we call this the distributive law, we’re trying to impose our algebraic understanding on the Greeks. Algebra has changed the way we think and has distorted the way we think about the mathematics of others.

The rise of algebra grew hand in hand with the rise of written mathematics. Before the printing press was invented, paper was rare and hence expensive. Mathematics was placed on paper, primarily as an archive. Calculation was mainly done with an abacus or with other physical representations. Reasoning was done orally and transferred that way from master to pupil. When paper became more common, more and more computations were done on paper.

Imagine I asked you to add 2 and 3 on your fingers. You would first hold up two fingers and then raise three more. In the end you would have five fingers raised, representing the fact that 2 + 3 = 5. However, if someone walked in the room after the computation, they would see only five fingers and not know how they came to be raised. They wouldn’t be able to tell if you made a mistake adding two plus two or if you added one and four. A paper computation is different. Someone looking at the sum 2 + 3 = 5 will see the elements of the computation on the paper after the work is completed.

The paper leaves a record, and the work can then be verified by someone familiar with the methods of computation. It in essence becomes a proof. Over the course of the last few centuries, mathematics gradually became more and more algebraic. As mathematicians became used to seeing their computations, they began to associate these ink marks with mathematics itself. It grew into the process of justifying a conclusion.

There are a number of benefits to algebra. For one thing, it’s short. It’s much easier to write 2 + 3 = 5 than “two things when combined with three other things become a total of five things.” As you can see, the rhetorical mathematics of the Greeks can appear quite cumbersome. But it’s also precise. The diagrams of the Greeks can be misleading. Consider two crossing lines and the angle “between them.” As you look at the diagram below realize that there are two perfectly valid angles between the lines and it’s unclear which one I’m referring to.

Is the angle between the lines the top or the left angle?

Algebra is viewed as infallible. Words can be ambiguous and diagrams misleading, but no one will question if 2 + 3 is 5. The more aspects of mathematics that could be boiled down to symbolic manipulation, the more reliable it appeared to be.

This transformation changed the way we looked at mathematics. The symbols were no longer just a shorthand language for expressing ideas but also became the focus of mathematical thinking. Problems, relations, and methods rooted in the real world became replaced with the infamous x and the equations it inhabited. Rote manipulations according to preassigned rules replaced intuitive thought and reasoning. Many persons simply know the steps required to solve a problem but don’t really understand what they’re actually doing or why they’re doing it.

Consider the following analogy. My word processor in some sense understands the rules of English. If I type a singular noun followed by a plural verb, it will not only point out the mistake but even offer a suggestion on how to rephrase it. However, it would be foolish to suggest that my computer actually understands English. It has no concept of the ideas I’m trying to express with the words and often gives me bad advice precisely because it doesn’t understand the context. When a student says that they like math but they don’t get word problems, it’s almost exactly the same thing. They know rules for manipulating symbols, but they can’t use them to answer questions about the world since they don’t understand what they mean.

Let’s now look at the algebraic treatment of Egyptian mathematics. If you don’t know any algebra or find it particularly abhorrent, it won’t hurt you to skip what I’m about to do. Technically, what follows isn’t even Egyptian mathematics—it’s modern tools mimicking Egyptian forms. However, if you can tolerate some algebra, it will help you understand the difference between modern and ancient methods and perhaps give you some valuable insight into both.

Let’s first consider the Egyptian rule for doubling an even fraction. We know that 2 × h is d. We got this, of course, by taking half of 6. Here’s an algebraic version. Note that the first and last steps convert the expression back and forth between Egyptian and modern notations.

EXAMPLE: Using algebra, prove that 2 × h = d.

PROOF: 2 × h = 2 × 1/6 = 2/1 × 1/6 = 2×1/1×6 = 2/6 = 1/3 = d

PRACTICE: Using algebra, prove that 3 × as = f.

When I first showed you the doubling-even rule, I tried to convince you of it by showing you simple examples. Hopefully examining them enabled you to understand why it worked; however, it may not have. Examples only work well if you already have some intuitive model with which to compare them. If you don’t, then you need to examine many examples to build the intuition from scratch. So “proof” by example isn’t really a proof at all but simply an attempt to relate the current situation to something you already accept as true. The above algebra, in some sense, is proof. If you accept the rules of algebra, you have to accept the conclusion that 2 × h = d.

We still haven’t gone completely modern. Today we like to generalize. We don’t write something like a tree + a tree is two trees. It’s somehow redundant with a dog + a dog is two dogs. We want an expression that encompasses this idea in all its forms so we say x + x = 2x. The variable x, which we encounter so often in algebra, is nothing but a pronoun. Just like the word “it,” x appears in many mathematical sentences, taking on many different meanings. In general, it just means “some number.”

The rule 2 × h = d is no different than the rule 2 × ak = l. This suggests that just as we replace “dogs” and “trees” with x, we need to do the same with 6 and 18. However, they’re both even, and the rule won’t work properly if they’re odd. Nothing about x suggests that it is even. We now need to ask ourselves, what’s special about even numbers? The answer is that they’re all twice a whole number. The numbers 6 and 18 are 2 × 3 and 2 × 9, respectively. This means that an even number can be expressed as 2x and hence even fractions can be written as  , where x is assumed to be a whole positive number.

, where x is assumed to be a whole positive number.

When we replace 6 and 18 with 2 × 3 and 2 × 9, the equations form a nice pattern. Consider that 2 × h = d becomes 2 ×  = d and 2 × ak = l becomes 2 ×

= d and 2 × ak = l becomes 2 ×  = l. If you notice the pattern, you are a good modern mathematician. In general 2 ×

= l. If you notice the pattern, you are a good modern mathematician. In general 2 ×  =

=  . Here’s the proof below.

. Here’s the proof below.

THEOREM: 2 × s:x = :x

PROOF:

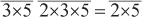

Let’s give the G rule the algebraic treatment. Consider ag d; = a;. This works because 2 × 15 is 30 and 30 ÷ 3 is 10. I can write ag d; = a; as

Note the extra “2 ×” in the second term. This makes it twice the first term. This algebraically is representing the fact that 15 × 2 = 30. The lack of a “× 3” in the last term means you get rid of it by dividing the middle term by 3. This represents 30 ÷ 3 = 10. The 5 has no particular meaning. The “×2, ÷3” relationship would hold if we changed the 5 to 7 or any other number. The 5 above is our x in the equation. So we can write and prove the following:

THEOREM:

PROOF: LHS = 1/3x + 1/6x = 2/6x + 1/6x = 3/6x = 1/2x = RHS

PRACTICE: Prove g:x f:×g:×:x = f:x

Above we proved the “×2, ÷3” and the “×4, ÷5” forms of the G rule. For the G rule to work, all that’s important is that the number you divide by be 1 more than the number you multiply by. Let’s now generalize this concept. If we multiply by y, we need to divide by 1 more, or y + 1. Hence our generalized G rule becomes the following:

THEOREM:

PROOF:

As we look at the above algebraic representation of the G rule, we need to ask ourselves a few questions. While the above symbols precisely define and verify the relation, do they give us any real insight into the G rule? If I initially explained the rule in these symbolic terms, would you have learned it as fast or would you have even understood it at all? Do you remember when I expressed the G rule as “if you add 1, then you have 1 more”? Such a simple understanding of the rule seems obscured by the above symbolic representation. It’s still there. In the second line of the above proof there are two fractions: one with a numerator of y and the other with 1. The addition of the second fraction somehow embodies the idea of “add 1.” The next line in the proof has a single fraction with a numerator of y + 1, which embodies the idea of “1 more.” However, when most people apply the rules of algebra, they are performing rote operations and not trying to comprehend the ideas that the symbols embody.

The purpose of this essay is not to belittle algebra. Its precision is often necessary to firm up loose, intuitive ideas. The powers of computation can’t be denied. Rhetoric and visual models may increase understanding, but they are often cumbersome when seeking a specific answer to a question. It’s important to keep a balance between formal symbolic methods and their intuitive meaning. But this book is about Egyptian mathematics, and I doubt few people could argue that the above equations give any real insight into the mind of an ancient mathematician.