Chapter 3

Writing a Marketing Plan

In This Chapter

Reviewing planning rules, as well as some do’s and don’ts

Crafting an executive summary and refining your strategic objectives

Getting the whole perspective with a situation analysis

Defining your marketing program, including the details

Forecasting and controlling revenues and expenses

If you have a very simple business that makes more sales than it needs to and is already growing as fast as it can, then you don’t need a marketing plan. However, most businesses are a tad more complex and therefore do require a marketing plan. A marketing plan is basically just a description, in words and numbers, of how you plan to run your marketing program. Having this plan is important because it helps you identify, execute, and control the marketing activities that will produce a successful year. You should write one if you

Have a big enough business that organizing, controlling, and budgeting all your marketing activities is difficult without a formal structure: Most businesses are too complex for the marketer to hold all the variables in his or her head. A plan helps you identify the best practices, eliminate the unprofitable ones, and keep everything on schedule and on budget.

Face any challenges or uncertainties that can affect sales or profits: The planning process helps you think through what needs to be changed in order to improve your results.

Don’t already know exactly what the best way is to handle your business’s branding, pricing, communications, sales, and other marketing matters: Planning helps clarify and control all the elements of your marketing plan.

Naturally, planning takes time and energy. Yet less than a quarter of all businesses go to the effort of developing a careful marketing plan. That’s too bad, because they miss the benefits, which save so much time and money later on that the extra, upfront effort required to create the plan always has big returns.

Another big benefit of planning is that it gets you thinking creatively about your marketing program. As you plan, you find yourself questioning old assumptions and practices and thinking about new and better ways to boost your brand and optimize sales and profits.

If your business doesn’t have a marketing plan, or even if it does and you want to improve that plan, this chapter is here to help. It shows you how to draft your own plan or revise your current plan so you can improve your bottom line.

Reviewing the Contents of a Good Plan

Before you can write a successful marketing plan for your business, you need to know the ins and outs of what a marketing plan includes. Marketing plans vary significantly in format and outline, but all of them have sections about the following:

Your current position: This is in terms of your product, customers, competition, and broader trends in your market.

What results you got in the previous period (if you’re an established business, that is): You need to look at sales, market share, and possibly also profits, customer satisfaction, or other measures of customer attitude and perception. You may also want to include measures of customer retention, size and frequency of purchase, or other indicators of customer behavior, because they’re often helpful in thinking about where to focus your marketing efforts in the future. Identifying the key things that customers desire and how your product matches up with those attributes are also important considerations.

Lessons learned: A postmortem on the previous period helps identify any mistakes to avoid, insights to take advantage of, or major changes that may present threats or opportunities.

Your strategy: This is the big focus of your plan and the way you’ll grow your revenues and profits. Keep the strategy statement to a few sentences so that everyone who reads it gets it at once and can remember what the strategy is.

The details of your program: You want to cover all your company’s specific activities in this section. Group them by area or type, with explanations of how these activities fit the company’s strategy and reflect the current situation.

The numbers: These definitely include sales projections and costs but may also include market share projections, sales to your biggest customers or distributors, costs and returns from any special offers you plan to use, sales projections and commissions by territory, and any other details that help you quantify your specific marketing opportunities and activities.

Your experimentation plans: If you have a new business or product, or if you’re experimenting with a new or risky marketing activity, set up a plan (or pilot) for how to test the waters on a small scale first. You need to determine what positive results you want to see before committing to a higher level. After all, wisdom is knowing what you don’t know — and planning how to figure it out.

Starting with baby steps

Optimizing your plan for flexibility means preserving your freedom of choice, avoiding commitments of resources, and spending in small increments so you can change the plan as you go. Ultimately, you need to decide how much flexibility you need and build it into the schedule and budget. You may want to consider milestones achieved as the mechanism to release additional activities or budget funds.

Maximizing efficiencies

If your business has been around the marketing block before and your plan builds on years of experience, you can more safely favor economies of scale over flexibility. (Economies of scale are the cost savings from doing things on a larger scale.) But always leave yourself at least a little wiggle room, because reality never reflects your plans and projections 100 percent of the time.

Understanding the Do’s and Don’ts of Planning

Marketing programs end up like leaky boats very easily. Each activity seems worthy at the time, but too many of them fail to produce a positive return — ending up as holes in the bottom of your business’s boat. Get too many of those holes, and the water inside the boat starts rising. The next sections share some of the common ways marketers lose money (so you can try to avoid them), plus two effective strategies for using your cash wisely.

Don’t ignore the details

Good marketing plans are built from details such as customer-by-customer, item-by-item, or territory-by-territory sales projections. Generalizing about an entire market is hard and dangerous. Your sales and cost projections are easier to get right if you break them down into their smallest natural units (such as individual territory sales or customer orders), do estimates for each of these small units, and then add up those estimates to get your totals.

Don’t imitate the competitors

You may be tempted to just do what your bigger competitors are doing, but don’t fall into that trap. You need to have some fresh ideas that make your brand and plan unique. Remember: Imitation isn’t a winning strategy in the long run.

Do find your own formulas for success

Start by building on whatever successes you’ve had in the past. For instance, if you ran an ad this year that got a good response, double or triple the number of ads of this kind in next year’s plan.

Don’t feel confined by last period’s budget and plan

When putting together your marketing plan, don’t allow past results to trap you in what you want to do. Repeat or improve the best-performing elements of the past plans and cut back on any elements that didn’t produce high returns. Every plan includes some activities and spending that aren’t necessary and can be cut out (or reworked) when you do it all over again next year. Be ruthless with any underperforming elements of last year’s plan! (If you’re starting a new business, at least this is one problem you don’t have to worry about. Yet.) Also, monitor your plan over the business cycle and adjust it as you go so you can catch problems early and avoid wasting too much time and money on underperforming activities.

Don’t engage in unnecessary spending

Always think through any spending and run the numbers before signing a contract or writing a check. Many of the people you deal with to execute your marketing activities are salespeople themselves. Their goal is to get you to buy their ad space, use their design or printing services, or spend money on fancy Web sites. They want your marketing money — and may care less whether you get a good return on it or not. So keep them on a tight financial rein.

Do break down your plan into simple subplans

If your marketing activities are consistent and clearly of one kind, you can go with a single plan. But what if you sell services (like consulting or repair) and also products? You may find that you need to work up one plan for selling products (perhaps this plan aims at finding new customers) and another plan for convincing product buyers to also use your services.

Analyze, plan, and budget sales activities by sales territory and region (or by major customer if you’re a business-to-business marketer with a handful of dominant companies as your clients).

Project revenues and promotions by individual product and by industry (if you sell into more than one).

Plan your advertising and other promotions by product line or other broad product category, as promotions often have a generalized effect on the products within the category.

Plan and budget publicity for your company as a whole. Only budget and plan publicity for an individual product if you introduce it or modify it in some way that may attract media attention. (Of course, exceptions exist for every rule. If you have a single bestselling product that carries your company, you need a publicity plan for it. You should also plan activities on the Web such as blogs and fun videos that go viral, so as to keep a buzz going about your star product.)

Plan and budget for brochures, Web sites, and other informational materials. Be sure to remain focused in your subject choices: Stick to one brochure per topic. Multipurpose brochures or Web sites never work well. If a Web site sells cleaning products to building maintenance professionals, don’t also plan for it to broker gardening and lawn-mowing services to suburban homeowners. Different products and customers need separate plans.

Writing a Powerful Executive Summary

A carefully crafted executive summary is an essential component of every marketing plan. An executive summary is a one-page plan that conveys essential information about your company’s planned year of programs and activities in a couple hundred well-chosen words or less. If you ever get confused or disoriented in the rough-and-tumble play of sales and marketing, this clear, one-page summary can guide you back to the correct strategic path. A good executive summary actually keeps everyone across the entire team (operations, sales, marketing, and outside contractors) on the same page. It’s a powerful advertisement for your program, communicating the purpose and essential activities of your plan in such a compelling manner that everyone who reads it eagerly leaps into action and takes the right steps to make your vision come true.

Efficiency oriented: A focus on efficiency means you’ll be scaling up known success formulas and aiming to increase the volume of business. For example, your summary may open with high sales goals and then review the various improvements over last year that you think will help achieve the new higher goals. If you have a pretty good marketing formula already, then the plan should help you refine and scale up that formula in order to achieve higher sales and profits.

Effectiveness oriented: This means a focus on testing and developing one or more new ways of marketing. For example, say your plan identifies a major opportunity or problem and a new strategy to respond to it. If you need to make major changes in your marketing program, then the plan is a tool for finding new, more effective marketing methods. It should include a wider range of marketing activities, along with ways of testing to see which ones work best.

If your plan has to help you overcome a problem, such as shrinking sales due to a large new competitor, state the problem clearly in the summary and also point out any links to other aspects of the business. Will the marketing plan have to be coordinated with a business plan that includes cost controls and layoffs? If so, state this fact upfront in your executive summary and make sure the rest of your business is working on the necessary changes so you aren’t stuck with a problem you don’t have full control over.

At the end of your executive summary, describe the bottom-line results: what your projected revenues will be (by product or product line, unless you have too many to list on one page) and what the costs are. Also, show how these figures differ from last year’s figures. Keep the whole summary under one page if you possibly can.

Preparing a Situation Analysis

A situation analysis is the one tool every marketer needs to ensure her marketing tactics are taking advantage of opportunities and solving for problems. In other words, it provides the context you need to move forward with your planning. Your situation analysis helps you define the context for your marketing plan by looking at trends, customer preferences, competitor strengths and weaknesses, and anything else that may impact sales. The question your situation analysis must answer is, “What’s happening?” To answer this question, you should analyze the most important market changes affecting your company. These changes can be the sources of problems or opportunities. (See Chapter 4 for formal research techniques and sources.)

To prepare a situation analysis, you must consider challenges and trends that can affect your marketing program, be prepared for economic cycles, and review your competition’s current status. After you identify these threats and opportunities, you need to give some serious thought to how to respond to them. Your marketing strategies are basically your responses to your strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, so your situation analysis feeds naturally into your strategies and plans.

Knowing what to include in your analysis

One good (and very traditional) way to organize a situation analysis is to write something for each of these four categories:

Strengths: Identify the strong points of your products, brand image, and marketing programs so you know what to build on in your plan. Your strengths are the keys to your future success. For example, if your Web site is a strength, then your plan should focus on making it even better, and your objectives should include increased Web sales.

Weaknesses: Pinpoint the areas in which your products, brand image, and marketing programs are relatively weak. For example, perhaps you have several older products that are losing to hot new competitors, or maybe you rely too heavily on newspaper advertising (which is a weakness, because newspaper readership is dropping). Your plan should propose changes that shore up or eliminate weak products and practices.

Opportunities: Your situation analysis needs to look for opportunities, such as a hot new growth market you can participate in (see Chapter 2 for help finding growth markets) or an exciting new way to reach prospective customers (see Part IV for a variety of ways).

Threats: A threat is any external trend or change that can reduce your sales or profits, or make it hard to achieve your growth goals. Common threats include new technologies that create new competitors, large competitors that can outspend you, and economic or demographic shifts that cut into the size or growth rate of your customer base. Your plan needs to respond to threats effectively, so identify the main ones as accurately and honestly as you can.

Table 3-1 shows you some of the typical marketing challenges and opportunities to get you thinking.

|

Table 3-1 Common Marketing Threats versus Opportunities |

|

|

Common Threats |

Common Opportunities |

|

New, tough competitors |

New products |

|

Economic problems or trends |

New ways to promote or sell |

|

Aging or loss of a customer base |

New types of customers to pursue |

Being prepared for economic cycles

When preparing your business’s situation analysis, you need to be in close contact with the pulse of the economy. Watch the leading published economic indicators and regularly monitor the numbers. If you notice a decline for more than two months in a row, look closely for any signs of sales slowdowns in your own industry and be prepared to take action.

Try to avoid being lulled into a false sense of security. Even though the economy in the United States (and many other countries) grew at a fairly steady rate for most of the 1990s, the majority of marketers forgot to keep an eye on the economic weather. When economic growth suddenly began to slow in December 2007, those same marketers faced major problems.

Avoid large marketing commitments. Expensive and/or long-term contracts for advertising, store rentals, and large inventories are dangerous in down times. For example, don’t purchase a full year of expensive advertising. Instead, buy month to month, even though doing so may cost you a bit more. The flexibility is well worth a slightly lower discount.

Keep an eye on your mix of fixed and variable costs. A fixed cost is one that doesn’t change with sales. For example, if you have a long-term lease on an office or warehouse, you must pay the costs of that facility no matter if your sales are up or down. Variable costs are costs that can fluctuate, such as the cost of goods sold and commissions. A marketing plan with a lot of variable costs is relatively recession-proof because your costs will go down proportionately to sales. Smart marketers avoid big payrolls when indicators make them nervous and instead favor commissioned salespeople or distributors over in-house sales staff.

Taking stock with a competitor analysis table

Gathering information about your competitors via an analysis table can help you draft a more complete situation analysis. A competitor analysis table summarizes the main similarities and differences between you and your competitors. You can compete more effectively after you have a good understanding of how your competitors operate and what their strengths and weaknesses are.

The kinds of information you can collect about your competitors varies significantly, so I can’t give you a pat formula, only suggestions. You can certainly gather and analyze samples of your competitors’ marketing communications, and you can probably find some info about how they distribute and sell, where they are (and aren’t) located or distributed, who their key decision-makers are, who their biggest and/or most loyal customers are, and even (perhaps) how much they sell. To get their customers’ perspectives, try pulling customer opinions from surveys or informal chats and group the information into useful lists to help you figure out the three most appealing and least appealing factors about each competitor. Ultimately, you want to gather any available data you can on all-important competitors and organize the data into a table for easy analysis.

A generic competitor analysis table should have entries on the following rows in columns labeled for Competitor #1, Competitor #2, Competitor #3, and so on:

Company: Describe how the market perceives it and its key product.

Key personnel: Who are the managers, and how many employees do they have in total?

Financial: Who owns it, and how strong is its cash position (does it have spending power, or is it struggling to pay its bills)? What were its sales in the last two years?

Sales, distribution, and pricing: Describe its primary sales channel, discount/pricing structure, and market share estimate.

Product/service analysis: What are the strengths and weaknesses of its product or service?

Scaled assessment of product/service: Explore relevant subjects such as market acceptance, quality of packaging, ads, and so on. Assign a score of between 1 and 5 (with 5 being the strongest) for each characteristic you evaluate. Then sum the scores for each competitor’s row to see which characteristic seems strongest overall.

A comparison of your ratings to your competitor’s ratings: If you rate yourself on these attributes too, how do you compare? Are you stronger? If not, you can include increasing your competitive strength as one of your plan’s strategic objectives (see the later “Clarifying and Quantifying Your Objectives” section for more on setting your objectives).

Explaining your marketing strategy

Your situation analysis identifies your weaknesses and threats, but it also identifies your strengths and opportunities. You need to take these findings and further clarify and build your marketing strategy around them in order to have the best chance for success. (Refer to Chapter 2 for help selecting a marketing strategy.)

For example, if you’re small and underfunded, and a major competitor just introduced a hot new competing product, then you face a major threat and shouldn’t try to go head to head with this competitor. Your strategy instead can be to sidestep the competition by targeting a protected, specialized segment of the market. You can also look for alternative ways to distribute and sell your product so that you aren’t competing directly with the competition for shelf space.

Clarifying and Quantifying Your Objectives

After you have a handle on your current situation and also have one or a few marketing strategies in mind to help you succeed, you need to think about what objectives (such as brand building or sales growth) are realistic and appropriate for you at this time. Marketing objectives are quantified, measurable goals such as “grow market share from 5 to 6 percent” and “shift 25 percent or more of our catalog customers over to Web site ordering.”

Objectives are such a key foundation for the rest of your plan that you can’t ever stop thinking about them. Yet for all their importance, they don’t need a lot of words. Devote a half-page to two pages to your objectives, at most. Check out the following sections for what you need to do to come up with objectives and then quantify them.

Think about the limitations in your resources

Don’t make your ambitions greater than the resources you have available to pull them off. If you’re currently the tenth-largest competitor, don’t write a plan to become the number one largest by the end of the year. Attempting that would likely require more marketing dollars, product inventory, and such than you actually have.

Don’t expect to make huge changes in customer behavior

You can move people and businesses only so far with a marketing program. If you plan to get employers to give their employees every other Friday off so those employees can attend special workshops your firm sponsors, well, I hope you have a backup plan. Employers don’t give employees a lot of extra time off, no matter how compelling your sales pitch or brochure may be. As the owner of a company that does management training, I’ve discovered that I need to adjust my firm’s products and services so they fit into the training time employers are willing to spare. Such adjustments are necessary; without them, your marketing program can’t succeed.

The same is true of consumer marketing. You simply can’t change strongly held public attitudes without awfully good new evidence and a lot of marketing communications. In your plan, first make sure your strategies are built on strengths and opportunities. Then set realistic objectives that fit your time, money, and talents. Remember: You want your plan to be 100 percent achievable.

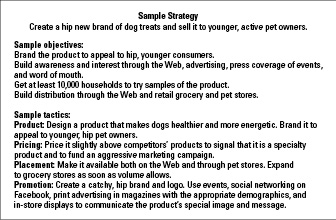

Sales are, of course, the ultimate objective of any marketing plan, so also include a realistic objective for how much you hope to sell. People usually define sales in terms of dollars of sales revenue, but that’s not all that helpful in the strategic part of your plan. Instead, try to find a way to measure how well you’re doing at reaching your target customers. For example, if you’re launching a new pet treat, you can set an objective of getting at least 100,000 households to buy and try your product. This objective helps keep you focused on the all-important goal of spreading the product throughout your market. If enough households try and like your product, then you should get plenty of repeat business from them, and future sales should be robust, assuming you find ways to remind people to purchase (either by marketing on the Web, by sending them direct mail or e-mail about the product, or by placing the product in grocery or pet stores where they’ll see it). Check out Figure 3-1 for an example of how a marketing strategy leads first to specific marketing objectives and then marketing tactics.

Figure 3-1: Seeing how objectives and tactics flow from your marketing strategy.

Your strategies accomplish your objectives through the tactics (the Five Ps) of your marketing plan. (See Chapter 1 for an explanation of the Five Ps.) The plan itself explains how your tactics accomplish your objectives through your marketing program.

Summarizing Your Marketing Program

A marketing program (which I fully define in Chapter 1) is the combination of marketing activities you use to influence a targeted group of customers to purchase a specific product, product line, or service. Usually you find it useful to include tactics in all five of the marketing Ps: product, price, placement, promotions, and people (refer to Figure 3-1 for a helpful example).

As you think about your plan’s tactics, drill down to the specifics of how to execute the plan and do whatever research is needed to work out the details. Perhaps you’re considering using print ads in trade magazines to let retail store buyers know about your hot new line of products and the in-store display options you have for them. That’s great, but now you need to get specific by picking some magazines. (Call their ad departments for details on their demographics and prices; see Chapter 7 for additional guidance on placing print ads.) You also need to decide how many and what type of ads to run and then price out this advertising program.

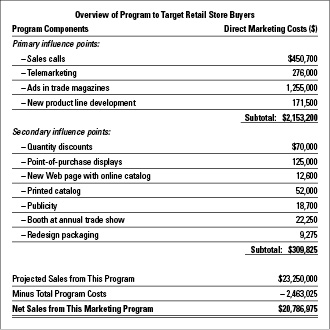

Do the same analysis for each of the items on your list of program components. Work your way through the details until you have an initial cost figure for what you want to do with each component. Total these costs and see whether the end result seems realistic. Is the total cost too big a share of your projected sales? Or (if you’re in a larger business) is your estimate higher than the boss says the budget can go? If so, adjust and try again. After a while, you get a budget that looks acceptable on the bottom line and also makes sense from a practical perspective.

Figure 3-2: A program budget, prepared on a spreadsheet.

This company’s secondary components don’t use much of the marketing budget when compared to the primary components (which use 87 percent of the total budget). But the secondary components are important, too. A new Web page is expected to handle a majority of customer inquiries and act as a virtual catalog, permitting the company to cut way back on its catalog printing and mailing costs. Also, the company plans to introduce a new line of floor displays for use by selected retailers at the point of purchase. Marketers expect this display unit, combined with improved see-through packaging, to increase turnover of the company’s products in retail stores.

Exploring Your Program’s Details

A good plan is nothing without details, and a good marketing plan is no different. After outlining your marketing program (which I walk you through in the preceding section), you need to explain the details of how you plan to use each component in your program. Devote a section to each component, which means the details portion of your plan may be quite lengthy (give it as many pages as necessary to lay out all the facts). The more of your thinking you get on paper, the easier implementing the plan will be later — as will rewriting the plan next year.

Although this portion is the lengthiest part of your plan, I’m not going to cover it in depth here. You can find details about how to use specific components of a marketing program, from product positioning to Web pages to pricing, in Parts III, IV, and V.

At a minimum, this part of the plan should have sections covering the Five Ps — the product, pricing, placement (or distribution), promotion (how you communicate with and persuade customers), and people (salespeople, customer service staff, distributors, and so on). But more likely, you’ll want to break these categories down into more specific areas. (If you’re pressed for time or want more guidance, try using the detailed marketing plan template that comes with my book, Marketing Kit For Dummies, 3rd Edition [Wiley].)

Managing Your Marketing Program

The main purpose of the management section of your marketing plan is simply to make sure that enough warm bodies are in the right places at the right times to get the work done. This section summarizes the main activities that you and your marketing team must perform in order to implement your marketing program. Use this section to assign these activities to individuals, justifying the assignments by considering issues such as an individual’s capabilities, capacities, and how the company will supervise and manage that individual.

Sometimes the management section gets more sophisticated by addressing management issues, like how to make the sales force more productive, or whether decentralizing the marketing function is worthwhile. If you have salespeople or distributors, develop plans for organizing, motivating, tracking, and controlling them. Also, develop a plan for them to use in generating, allocating, and tracking sales leads. Start these subsections by describing the current approach and do a strengths/weaknesses analysis of that approach, using input from the salespeople or distributors in question. End by describing any incremental changes or improvements you can think to make.

Projecting Expenses and Revenues

At this stage of preparing your marketing plan, you need to put on your accounting and project management hats. (Perhaps neither hat fits you very well, but try to bear them for a day or two.) You need these hats to

Estimate future sales, in units and dollars, for each product in your plan.

Justify these estimates and, if they’re hard to justify, create worst-case versions.

Draw a timeline showing when your program incurs costs and performs program activities. (Doing so helps with the preceding section, and also gets you prepared for the unpleasant task of designing a monthly marketing budget.)

Write a monthly marketing budget that lists all the estimated costs of your programs for each month of the coming year and breaks down sales by product or territory and by month.

If your cash-based projection shows a loss some months, fiddle with the plan to eliminate that loss (or arrange to borrow money to cover the gap). Sometimes a careful cash-flow analysis of a plan leads to changes in underlying strategy. One business-to-business marketer I worked with adopted the goal of getting more customers to pay with credit cards rather than invoices as the primary marketing objective. The company’s business customers cooperated, and average collection time shortened from 45 days to less than 10, greatly improving the business’s cash flow as well as its spending power and profitability.

Buildup forecasts

Buildup forecasts are predictions that go from the specific to the general, or from the bottom up. If you have sales reps, ask them to project the next period’s sales for their territories and to justify their projections based on their anticipated changes in the situation. Then combine all the sales force’s projections to obtain an overall figure.

If you have few enough customers that you can project per-customer purchases, build up your forecast this way. You may want to work from reasonable estimates of the amount of sales you can expect from each store carrying your products, or from each thousand catalogs mailed. Whatever the basic building blocks of your program, start with an estimate for each element and then add these estimates up.

Indicator forecasts

Indicator forecasts link your projections to economic indicators that ought to vary with sales. For example, if you’re in the construction business, you find that past sales for your industry correlate with GDP (gross domestic product, or national output) growth. So you can adjust your sales forecast up or down depending on whether experts expect the economy to grow rapidly or slowly in the next year.

Multiple scenario forecasts

If you liked what-if stories as a child, you’ll love multiple-scenario forecasts. They start with a straight-line forecast in which you assume that your sales will grow by the same percentage next year as they did last year. Then you make up what-if stories and project their impact on your plan to create a variety of alternative projections.

You may try the following scenarios if they’re relevant to your situation:

What if a competitor introduces a technological breakthrough?

What if your company acquires a competitor?

What if Congress deregulates/regulates your industry?

What if a leading competitor fails?

What if your company experiences financial problems and has to lay off some of its sales and marketing people?

What if your company doubles its ad spending?

For each scenario, think about how customer demand may change. Also consider how your marketing program would need to change in order to best suit the situation. Then make an appropriate sales projection. For instance, if a competitor introduced a technological breakthrough, you may guess that your sales would fall 25 percent short of your straight-line projection.

For example, the Cautious Scenario projection estimates $5 million, and the Optimistic Scenario projection estimates $10 million. The probability of the Cautious Scenario occurring is 15 percent, and the probability of the Optimistic Scenario occurring is 85 percent. So you find the sales projection with this formula: [($5,000,000 × 0.15) + ($10,000,000 × 0.85)] ÷ 2 = $4,625,000.

Time-period forecasts

To use the time-period forecast method, work by week or by month, estimating the size of sales in each time period, and then add these estimates together for the entire year. This approach helps you when your program (or the market) isn’t constant across the entire year. Ski resorts use this method because they get certain types of revenues only at certain times of the year. Marketers who plan to introduce new products during the year or use heavy advertising in one or two pulses (concentrated time periods) also use this method because their sales go up significantly during those periods.

Creating Your Controls

The controls section is the last and shortest section of your plan — but in many ways, it’s the most important because it allows you and others to track performance. Identify some performance benchmarks and state them clearly in your plan. For example:

All sales territories should be using the new catalogs and sales scripts by June 1.

Revenues should grow to $75,000 per month by the end of the first quarter if the promotional campaign works according to plan.

These statements give you (and your employers or investors) easy ways to monitor performance as you implement the marketing plan. Without them, nobody has control over the plan; nobody can tell whether or how well the plan is working. But with these statements, you can identify unexpected results or delays quickly — in time for appropriate responses if your controls were designed properly.

By the time you think through and write down all these elements of a good plan, you may feel quite invested in your plan. Be careful! You mustn’t think of your plan as written in stone. In fact, your plan is just a starting point. As you implement it throughout the coming year, you’ll discover that some things work out the way you planned, and others don’t. Good marketers revisit their plans and adjust them as they go. The idea is to use a plan to help you be an intelligent, flexible marketer, not a stubborn one who refuses to learn from experience.

By the time you think through and write down all these elements of a good plan, you may feel quite invested in your plan. Be careful! You mustn’t think of your plan as written in stone. In fact, your plan is just a starting point. As you implement it throughout the coming year, you’ll discover that some things work out the way you planned, and others don’t. Good marketers revisit their plans and adjust them as they go. The idea is to use a plan to help you be an intelligent, flexible marketer, not a stubborn one who refuses to learn from experience. The more unfamiliar you are with writing a marketing plan, the more flexibility and caution your plan needs, so make flexibility your first objective if you’re creating a marketing plan for the first time. Consider crafting a gradual plan that includes a pilot phase with a timeline and alternatives or options in case of problems. For example, instead of taking advantage of cheaper bulk printing with a vendor you don’t know for a marketing piece you’ve never tested, use short runs of marketing materials at the local copy shop.

The more unfamiliar you are with writing a marketing plan, the more flexibility and caution your plan needs, so make flexibility your first objective if you’re creating a marketing plan for the first time. Consider crafting a gradual plan that includes a pilot phase with a timeline and alternatives or options in case of problems. For example, instead of taking advantage of cheaper bulk printing with a vendor you don’t know for a marketing piece you’ve never tested, use short runs of marketing materials at the local copy shop. The Conference Board (

The Conference Board (