Chapter 15

Finding the Right Pricing Approach

In This Chapter

Facing the facts about pricing

Establishing or modifying your list price

Crafting price-based special offers

Staying out of legal hot water

Getting the price just right is the hardest task you face as a marketer, but finding the right pricing approach makes success much easier to achieve. The bottom line is that the customer needs to pay — willingly and, you hope, rapidly — for your products or services. But how much will he or she pay? Should you drop your prices to grow your market? Or would raising the price and maximizing profits be better? What about discounts and special promotional pricing? Getting the price part of your marketing plan right is hard, but this chapter helps you through it by giving you a clearer idea about the many questions you may have about pricing and what it means to your bottom line.

Eyeing Pricing Opportunities and Constraints

Many companies fall prey to the myth that customers choose a product based on its list price (the published selling price in a catalog, on a price list, or on the product itself). Setting your list prices lower than you need to is tempting. So is trying to boost sales by offering discounts or free units. However, being too liberal with price cuts, discounts, and free offers is a mistake as well. So where exactly do you set your prices? The following sections provide you with some strategies you can undertake when setting your pricing, including increasing the price to sell more, staying clear of underpricing, and looking at how pricing affects what your customers buy. The goal is to feel that you’re in control of your margins and able to make plenty of sales at the price points you choose.

Raising your price and selling more

If you insist on selling your product or service on the basis of low price, your customers will get in the habit of shopping for the lowest price. To counteract that, take appropriate action by combining conservative pricing with aggressive branding to win a higher net price and a bigger profit margin. Remember: Your goal should be to see how much you can sell your product for, not how little.

To raise your price and sell more, you may decide to

Build brand equity: Better-known brands command a premium price.

Increase quality: People talk up a good product, and that word of mouth earns the product a 5 to 10 percent higher price than the competition.

Use prestige pricing: Giving your product a high-class image can boost your price 20 to 100 percent.

Create extra value through time and place advantages: Customers consider the available product worth a lot more than the one they can’t get when they need it. (That’s why a cup of coffee costs twice as much at the airport. Who’s really going to leave the terminal, get in a taxi, and go somewhere else to save a couple bucks?)

Avoiding underpricing

You’re always going to have an easier time lowering a price than raising it. In general, you want to set price a bit on the high side and see what happens. You can take back any price increase with a subsequent price cut — just be wary of underpricing your product or service because you may find you’ve given away your profits.

Exploring the impact of pricing on customers’ purchases

Price sensitivity is the degree to which purchases are affected by price level. You need to estimate how price sensitive your customers are. Specifically, you want to be able to predict how many sales you’ll lose or gain from a specific increase or decrease in your sales price. This information can tell you whether you’ll profit from a change in price.

However, if you find new competitors with lower prices than yours and they’re taking some of your business, then you can conclude that your customers are price sensitive. You need to match the competitive prices in order to stop losing customers. That’s too bad, but it happens often, and when it does, you have to turn to cost controls if you want to save your profit margins.

Finding profits without raising prices

Check to see how quickly you’re making collections. Cutting that time may make up the needed profits without any price increase.

Look at all the discounts and allowances you offer. These factors affect your revenues and profits, so you need to review them before assuming that price is the culprit. Are customers taking advantage of quantity discounts to stock up inexpensively and then not buying between the discount periods? If so, you have a problem with your sales promotions, not your list prices.

Examine how you assess fees. Perhaps your company is failing to collect the appropriate fees in some cases. (This one is particularly important if you’re in a service business that charges a base price plus fees for special services and extras.)

Determine whether your fee structure is out of date. If it is, your cost structure likely isn’t reflected accurately. For example, a bank that charges a low price for standard checking accounts, plus a per-check processing fee, may well find its profits slumping as customers switch to automated checking over the bank’s computers. Why? Because banks often set the introductory fees for this service low or waive them to stimulate trials. If so, the problem isn’t with the base price of a checking account, it’s with the nature of the fee structure.

Setting or Changing Your List Price

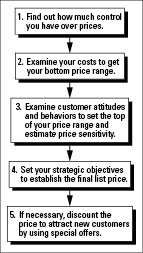

If you need to establish a price, you’re stuck with one of the toughest tasks anybody does in business. Surveys of managers indicate they suffer from a high degree of price anxiety. The sections that follow take you through the process of setting or changing your price logically, step by step. (Figure 15-1 illustrates the process that I describe in the following sections.)

Figure 15-1: A helpful pricing process.

Step 1: Figure out who sets prices

The step of determining who sets the price isn’t obvious. You, as the marketer, can set a list price. But the consumer may not ultimately pay your price. You may encounter a distributor or wholesaler as well as a retailer, all of whom take their markups. Furthermore, the manufacturer generally doesn’t have the legal right to dictate the ultimate selling price. The retailer gets that job. So your list price is really just a suggestion, not an order. If the retailer doesn’t like your suggested price, she sells your product for another price.

Marketers who operate in or through a multilevel distribution channel, meaning that they have distributors, wholesalers, rack jobbers (companies that keep retail racks stocked), retailers, agents, or other sorts of intermediaries, need to establish a trade discount structure. Trade discounts (also called functional discounts) are what you give these intermediaries. They’re a form of cost to the marketer, so make sure you know the discount structure for your product before you move on. Usually, marketers state the discount structure as a series of numbers, representing what each of the intermediaries gets as a discount. But you take each discount off the price left over from the discount before it, not off the list price. See the nearby sidebar for more detailed advice.

Step 2: Examine your costs

In practice, you may not have good, accurate information on the true costs of a specific product or service. That’s why you need to carefully examine your costs. Take some time to try to estimate what you’re actually spending and remember to include some value for expensive inventories if they sit around for a month or more (assume you’re paying interest on the money tied up in those products to account for the loss of having your capital wrapped up in inventory).

After you examine your costs carefully, you should have a fairly accurate idea of the minimum amount you can charge — at the very least, that charge should be your actual costs. (Okay, maybe sometimes you want to give away a product for less than the cost in order to introduce people to it, but don’t use this ploy to take customers from competitors or you can be sued for dumping. See the later “Staying Out of Trouble with the Law” section for the dirt on dumping.) More often, you need a price that includes the cost plus a profit margin — say, 20 or 30 percent. So that means you have to treat your cost as 70 or 80 percent of the price, adding in that 20- or 30-percent margin your company requires.

This cost-plus-profit figure is the bottom of your price range (see Figure 15-2). Now you need to see whether customers permit you to charge this price — or even (if you’re lucky) allow you to charge a higher price.

Figure 15-2: Defining your price range.

Step 3: Evaluate customers’ price preferences

Your costs and profit requirements impose a lower limit on price, but your customers’ price preferences impose an upper limit. You need to define both of these limits to know your possible price range. That means you need to figure out what price customers are willing to pay.

In Figure 15-2, I label the price that customers favor as customers’ preference. Note that customer preference may not be the upper limit. If customers aren’t too price sensitive, they may not notice or care if you set your price somewhat higher than their preferred price.

Pricing experts sometimes call the difference between the customer’s desired price and a noticeably higher price the indifference zone. Within the indifference zone, customers are indifferent to both price increases and price decreases. However, the zone gets smaller (on a percent basis) as the price of a product increases. How big or small is the zone of indifference in your product’s case? (See the earlier “Exploring the impact of pricing on customers’ purchases” section for help gauging your customers’ price sensitivity.) The zone is small if your customers are highly price sensitive; the zone is large if they aren’t that price sensitive.

Through these sorts of activities, I assume you have at least back-of-the-envelope figures for your customers’ preferred price and how much higher you can price without drawing attention. Guess what? You’ve established the top of your price range!

The simplest approach to pricing is to set your price at the top of the range. As long as the price range is above your bottom limit (as long as your preferred price plus the indifference zone is equal to or greater than your cost plus your required profit), you’re okay. But you can’t always set your price at the top of the range. In the next step of the pricing process, I show you how to figure out what your final price should be.

Step 4: Consider secondary influences on price

Your costs and your customers’ preferred prices aren’t the only factors you need to consider when trying to set or change your price. Yes, they’re your primary considerations, but you also need to examine secondary influences. These factors may influence your decision by forcing you to price in the middle or bottom of the price range rather than at the top, for example.

Following are the key secondary influences you need to consider:

Competitive issues: Do you need to gain market share from a close competitor? If so, either keep price on par with your competitor’s pricing and do aggressive marketing or adjust your price to be slightly (but noticeably) below the competitor’s price.

![]() If you’re tempted to undercut a key competitor, be careful not to start a price war in which you and the competitor keep trying to undercut each other’s prices until you’re both giving your products away.

If you’re tempted to undercut a key competitor, be careful not to start a price war in which you and the competitor keep trying to undercut each other’s prices until you’re both giving your products away.

Likely future price trends: Are prices trending downward in this market? Then you need to adjust your figures down a bit to stay in sync with your market.

Currency fluctuations: Any fluctuation in currency may affect your costs and, consequently, your pricing options. If you’re concerned that you may take a hit from the exchange rate, better to be safe than sorry and price at the high end of the range.

Product line management: This factor may dictate a slightly lower or higher price. For example, you may need to price a top-of-the-line product significantly higher than others in its line just to make it clear to the customer that this product is a step above its competition.

Step 5: Set your strategic objectives

You may have objectives other than revenues and profit maximization. That’s fine, but you need to clearly understand what those other objectives are. For instance, many marketers price near the bottom of their price range to increase their market share. (They price low because a high market share later on will probably give them more profits. It’s an investment strategy.)

Sometimes marketers price low because they want to minimize unit volume, like when they’re introducing a new product. They may not have had the capacity to sell the product to a mass market at first, so they skimmed the market by selling the product at such a high price that only the very wealthy or least price-sensitive customers could buy it. Then they lowered prices later on, when they’d made maximum profits from the high-end customers and had added production capacity.

Step 6: Master the psychology of prices

To effectively set or change your price, you must possess a clear understanding of how customers perceive price. Believe it or not, psychology plays a big role in this process. What you set as your price and how customers perceive that price can have a significant impact on your level of sales. The following sections help you understand the psychology behind three different pricing methods available to you.

Odd-even pricing

The odd-even pricing method lowers the rounded-up price of an object by a cent or so, which people perceive as significantly lower than the rounded-up price. For example, if the top of your price range for a new child’s toy is $10, you probably want to drop the price down to $9.99 because most customers think this price is much cheaper. Assuming your customers are in any way price sensitive, they buy more of the lower-priced product, even though the price difference amounts to only one cent. Why? Because people perceive prices ending in 9 as cheaper — generally 3 to 6 percent cheaper in their memories than the rounded-up price. It’s just something about the way your customers see your price, and you can take advantage of it.

Price lining

The price lining method fits your product into a range of alternatives, giving the product a logical spot in customers’ minds. By adjusting your price to make it fit into your product line or into the range of products sold by your retailers or distributors, you make it clear what the competition is and how consumers should think about the product’s value.

Notice that Apple uses two other strategies along with its price lining strategy — and you can too. First, Apple uses odd-even pricing for the individual prices ($2,499 versus $2,500). Doing so makes the line of products appear at first to be a bit more affordable. Second, Apple uses the phrase “starts at” to describe its list prices. By doing so, Apple encourages purchasers to add extras, such as memory upgrades and software that often add hundreds to the list price. Apple could’ve integrated more options into its line at firmer list prices, but the result would’ve been far more confusing and would’ve given consumers less choice. Choice equals control, and consumers of complex products like laptops often prefer to feel in control of the details.

Competitive pricing

The competitive pricing method calls for you to set your price relative to that of an important competitor or set of competitors. Should you price above or below a tough competitor? That decision depends on whether you offer more or fewer benefits and higher or lower quality. It may also depend on the relative values of your brands. If you’re facing a larger competitor with a famous brand name, recognize that you may need to price 5 to 10 percent less just because your brand isn’t as well-known.

Some competitors try to convince customers that their product is better but costs less than the competitors’ products. Nobody believes this claim — unless you present evidence. If you do, customers will love you. After all, everyone hopes to get more for less! For example, a personal computer with a new, faster chip may really be better but cost less, and a new antiwrinkle cream may work better but cost less if you’ve discovered a new formula. As long as you have — and can communicate to the customer — a plausible argument, you can undercut your competitors’ prices at the same time that you claim superior benefits. But make sure you back up the claim, or the customer may assume that your lower price means your product is inferior.

Designing Special Offers

Special offers are temporary inducements to make customers buy on the basis of price. Regardless of the form special offers appear in (typically a coupon), they give consumers or intermediaries a way to get the product for less — at least while the offer lasts. When you design a special offer such as a temporary discount or a redeemable coupon, make the offer as large — but only just as large — as needed to attract attention and stimulate increased purchases. A discount of 1 percent may not be enough to motivate customers, but a 5-percent discount may attract a lot of action. Similarly, a 25-cent coupon is too small for most people to bother with, but a coupon worth a dollar or more often generates action. The following sections cover some types of special offers you can try, as well as how to use them, how to determine their cost, and when to end them.

Creating coupons and other discounts

You can offer coupons, refunds, premiums (gifts), free extra products, free trial-sized samples, sweepstakes and other event-oriented premium plans, and any other special offer you can think up — just check with your lawyers to make sure the promotion is legal. (Legal constraints do exist. You can’t mislead consumers about what they get. And a sweepstakes or contest within the United States has to be open to all, not tied to product purchase. See the “Staying Out of Trouble with the Law” section later in this chapter for more on marketing’s legal no-nos.)

A large majority of all special offers takes the form of coupons (any certificate entitling the holder to a reduced price), which is why I focus on them in explaining how to design special offers in the next few sections.

Pick your medium

The design of your coupon depends on the medium you want to use to reach your target audience. The medium is the communication channel; it can be a newspaper, magazine, fax, mailing, or printable e-mail or Web site coupon. In today’s world, you’re no longer limited to printed, clip-out offers on paper. A small, blinking display ad on high-traffic Web sites (such as Facebook) or an e-mail to your house list can be just as effective — if not more so — than the traditional newspaper coupon.

Although newspapers used to be the most common way to distribute a coupon to customers, in today’s evolving technological world, the Internet has made getting coupons to the masses way easier and a lot more effective. When a customer does a key-term search on an Internet search engine, you can have your offer pop up on her screen. She can then click on a special landing page to find more information about the offer (see Chapter 10 for tips on Web marketing).

You can also use direct mailings and e-mails to pitch an offer; these options usually work best for a fairly big discount or a special bundled offer, because you need to have something newsworthy to write about. If you’re holding an event (such as a clearance sale), try using additional mediums (think transit and billboard ads, vehicle advertising, local television, and Web radio) to spread the word and turn out a crowd.

Craft the look and feel

To get a good feel for the options and approaches to coupons, collect a bunch of recent coupons from your own and other industries. And don’t forget to do key-term searches online, like your customers might, to see what special offers pop up on the Web. This collection of recent coupons and special offers gives you the current benchmark for your industry.

Appeal to intermediaries

If you’re promoting to the trade, marketers’ name for intermediaries such as wholesalers and retailers, then you can offer things like free-goods deals, buy-back allowances, display and advertising allowances, and help with their advertising costs (called cooperative, or co-op, advertising).

Figuring out how much to offer

How much of a deal should you offer customers in a coupon or other special offer? The answer depends on how much attention you want. Most offers fail to motivate the vast majority of customers, so keep in mind that the typical special offer in your industry probably isn’t particularly effective. A good ad campaign probably reaches more customers.

Forecasting redemption rates

Designing your offer isn’t the hardest part. The biggest trick is guessing the redemption rate (or percentage of people who use the coupon). You raise the stakes when you use big offers, which makes them riskier to forecast (good luck trying to forecast these rates). Test an offer on a small scale first and gather some real data about how it works. Then use the info in this section to help make your guesstimate a bit more accurate.

To forecast whether your coupon will have a high or low redemption rate, compare your offer to others. Are you offering something more generous or easy to redeem than you have in the past? Than your competitors do? If so, you can expect significantly higher-than-average redemption rates — maybe twice as high or higher.

After you find an offer that produces added sales, check that it’s profitable. If sales only go up a little but lots of existing customers make their regular purchases at a discount, then you won’t make a profit from the offer. What you want is lots of new customers who buy because of the offer and then become regular users. If you don’t get these new customers the first time, try a different medium that reaches new prospects better.

Many coupons don’t shift the price very far beyond the indifference zone (see the earlier “Step 3: Evaluate customers’ price preferences” section) — that’s why they generally attract those fringe customers who buy on price but don’t attract the core customers of other brands. That’s also why redemption rates are only a few percent, on average. However, if your coupon does shift the price well beyond the indifference zone, you’re likely to see a much higher redemption rate than usual.

Predicting the cost of special offers

After you think about the redemption rate that I cover in the previous section, you need to determine what the cost of your special offer will be. For example, say you believe that 4 percent of customers will redeem a coupon offering a 10-percent discount on your product. To estimate the cost of your coupon program, you must first decide whether this 4 percent of customers accounts for just 4 percent of your product’s sales over the period in which the coupon applies. Probably not. Customers may stock up in order to take advantage of the special offer, so you must estimate how much more than usual they’ll buy.

If you think customers will buy twice as much as usual (that’s a pretty high figure, but it makes for a simple illustration), just double the average purchase size. Four percent of customers, buying twice what they usually do in a month (if that’s the term of the offer), can produce how much in sales? Now apply the discount rate to that sales figure to find out how much the special offer may cost you. Can you afford it? Is the promotion worth the money? That’s for you to decide, and it’s a true judgment call — the math can’t tell you what to do.

Keeping special offers special

A price cut is easy to do, but it’s hard to undo. A special offer allows you to temporarily discount your product’s or service’s price while still maintaining the list price at its old level. When the offer ends, the list price is the same — you haven’t permanently given anything away.

Here are some cases in which maintaining your list price can be important:

When your reason for wanting to cut the price is a short-term one, like wanting to counter a competitor’s special offer or respond to a new product introduction

When you want to experiment with the price (to find out about customer price sensitivity) without committing to a permanent price cut until you see the data

When you want to stimulate consumers to try your product or service, and you believe that after they try it, they may like it well enough to buy it again at full price

When your list price needs to stay high in order to signal quality (prestige pricing) or be consistent with other prices in your product line (price lining strategy)

When your competitors are all offering special lower prices and you think you have no choice because consumers have come to expect special offers

Sometimes competitors make such heavy use of special offers that consumers begin to expect them all the time and wait for an offer before they buy. These competitors have effectively lowered their prices, because consumers are no longer willing to buy at list price and assume they won’t ever have to. If this situation happens in your industry and you’re a relatively small competitor, you may be stuck with having to make special offers every month. But try not to create the problem through your own marketing. I recommend keeping special offers special as opposed to the norm.

Staying Out of Trouble with the Law

Price fixing: Don’t agree to (or even talk about) prices with other companies. The exception is a company you sell to — but note that you can’t force any company to resell your product at a specific price.

Price fixing in disguise: Shady marketers have tried a lot of ideas, none of which work. If your competitors want you to require the same amount of down payment, start your negotiations from the same list prices as theirs, use a standardized contract for extending credit, or form a joint venture to distribute all of your products (at the same price), recognize these seemingly friendly suggestions for what they are — forms of price fixing. Just say no. And in the future, refuse even to take phone calls from competitors who talk about price fixing.

Price fixing by purchasers: If retailers you sell to are joining together in order to dictate the wholesale prices they want you to give them, that may also be price fixing. Have a lawyer review any such plans.

Exchanging price information: You can’t talk to your competitors about prices. Ever. Okay? If it comes to light that anyone in your company gives out information about pricing and receives some in return, you’re in big trouble, even if you don’t feel you acted on that information. Take this warning seriously. (By the way, price signaling — announcing a planned price increase — is sometimes seen as an unfair exchange of price information, because competitors may use such announcements to signal to others that everyone should make a price increase.)

Bid rigging: If you’re bidding for a contract, the preceding point applies. Don’t share any information with anyone. Don’t compare notes with another bidder. Don’t agree to make an identical bid. Don’t split by agreeing not to bid on one job if the competitor doesn’t bid on another. Don’t mess with the bidding process in any manner, or you’ll be guilty of bid rigging.

Parallel pricing: In some cases, the U.S. government can charge you with price fixing, even if you didn’t talk to competitors, just because you have similar price structures. After all, the result may be the same — to boost prices unfairly. In other cases, the law considers similar prices as natural. To be safe, avoid mirroring competitors’ prices exactly.

Price squeezes, predatory pricing, limit pricing, and dumping: To the average marketer, these four illegal acts are effectively the same (although they’re tested under different U.S. regulations). They all involve using prices to push a competitor out of business, or to push or keep a competitor out of a particular market. Following are brief explanations of each act:

• The classic squeeze involves setting wholesale prices too high for small-sized orders. It drives the independent or small retailer out of business, giving unfair advantage to the big chain buyers that can qualify for a volume discount.

• At the retail level, predatory pricing involves setting prices so low that local competitors can’t keep up. Predatory pricing is also used by chains and multinationals to drive locals out of business. If you’re pricing at or below cost, you’re probably engaging in predatory pricing.

• Similarly, if your prices are so aggressive that they lock other competitors out of a market (even if you price above cost), then you’re probably guilty of limit pricing.

• A variant of limit pricing is dumping, in which you try to buy your way into a new market by dumping a lot of product into that market at artificially low prices. Don’t ever do this.

Because so many pricing techniques are illegal, some people throw up their hands in despair. They say, “What can I do?” Well, trying to influence prices in certain ways is okay. You can offer volume discounts to encourage larger purchases, as long as those discounts don’t force anybody out of the market. And although you, as a marketer, can’t force retailers to charge a certain price for your product, you can encourage them to by advertising the suggested retail price and listing it as such on your product.

Additionally, you can always offer an effective price cut to consumers through a consumer coupon or other special offer (as explained earlier in this chapter). Retailers usually agree to honor such offers (check with an ad agency, the retailer, or a lawyer to find out how to form such contracts). However, if you offer a discount to your retailers, you can’t force them to pass that discount on to your customers. They may just put the money in the bank and continue to charge customers full price. Test such offers to see how your intermediaries respond before assuming the offer will reach all the way to the end consumer.