chapter four

RULES OF ORDER/SUSTAIN ATTENTION

Pay attention, get focused, be vigilant, stay on task, keep your eye on the ball, listen up, get your head in the game: these are just a few of the many ways we have of calling on that very basic human skill of paying attention.

There may be good reason for the variety of ways in which we ask each other to pay attention. In these fast-paced times, our attentional abilities are highly taxed. The world is demanding our attention at every turn and around every corner.

The ability to sustain focus is one of the building blocks of organization. It is step two in our process to help you become more organized. The first step is to establish emotional control—to “tame the frenzy.” Now we are ready to take the next step—to sustain attention and to stay focused for greater lengths of time.

Of course, asking people to pay attention is simple. But from a brain science perspective, the actual process of doing so is a remarkably involved task, requiring work from many distinct brain areas. Paying attention is far more complex than, for example, the act of looking at something or someone. Indeed, there are neuroscientists who devote lifetimes to the study of attention. Obviously we can’t go into that kind of depth here, but because the ability to pay attention is such a critical component of personal organization, it’s important that we understand something about how it works—particularly as our understanding of it has evolved and changed in the past few years.

The first step in what we call the “attentional process” is to orient to the stimulus, whether it’s the commercial on television, the teacher at the head of the classroom, or the red light flashing in the distance. Actually, let’s imagine that light flashing in the distance is the signal from a fire engine, racing down the street. You turn and look in the direction of that sound, as your brain locks in on it. Think about just that for a moment. Consider how quickly we stop, look, listen; how fast our reaction time is; and how, in the blink of an eye, we have identified what the vehicle is, what direction it’s coming from, and its probable purpose. Let’s add the whiff of smoke in the air, and you’ve deduced even further what is happening and where that fire engine is going. In doing all that you have still used three of your sensory modalities—auditory (hearing), visual (seeing) and olfactory (smelling). Your tactile (touching) and gustatory (tasting) senses will have to wait until dinner.

Next step in the attention process is our engagement with that information as the fire engine comes blasting by. First simple orientation to the noise, now lots of attention to detail. You notice it festooned with ladders and tanks, an impressive complement of modern firefighting equipment. You see the firefighters in their gear; you catch a fleeting glimpse of determined faces under their helmets. You read the lettering on the side of the truck and see which firehouse the engine has been dispatched from and recall that you’ve passed that building. Perhaps you even recall an episode from the television show Chicago Fire, a scene from the day your child’s class visited the local firehouse or something you read in the local paper about the fire department requesting funds for new equipment. You are now attending to this “stimulus” fully, pulling in and synthesizing bits of information from various parts of the brain. You are homing in on the sound and bringing to it the full and awesome powers of sustained, focused attention. And yet it’s all happening in a matter of seconds. Take a moment to acknowledge that innate human skill—and to congratulate yourself on your facility for being able to attend to a great deal of information so quickly! Remember also that no matter how disorganized you may feel or how inattentive you may have been on the job or at home lately, chances are that if a fire engine really did come barreling down the street right now, you’d be able to attend to it with the same richness and breadth of cognitive resources we have described.

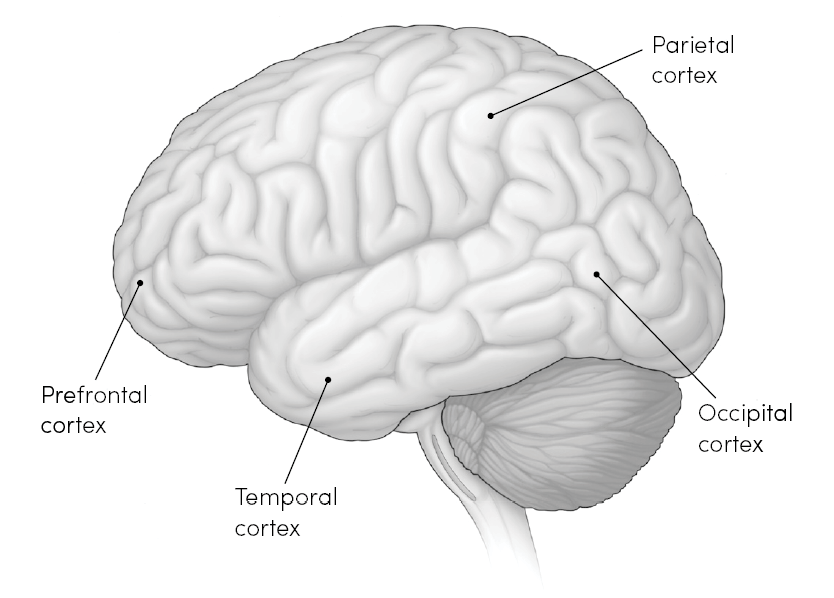

Let’s talk a little about how you are able to do that and about important areas of the brain “cortex,” the area we must pay attention to when discussing this. Cortex comes from the Latin word for bark. It is the coating of the brain surface, those folds/crevices we mentioned earlier—and much of the information processing for the brain happens there. There are several specialized cortical areas, serving different functions.

One way of describing the brain’s attentional workings is to begin at the back (posterior) of the brain cortex and move forward, somewhat akin to the way the fire-engine sound began in the background, in the distance, and then became clearer, as the truck raced toward you. Similarly, sensory information taken in by your eyes is received in the back of the brain (occipital cortex) and moves forward in the temporal and parietal cortices.

Source: National Institute of Drug Abuse Teaching Slides

The parietal cortex is involved in scanning the environment around you, analyzing motion, considering spatial relations and orienting you in time and space. It is key in that first orienting step, in which you focus on new stimuli. The temporal cortex is also involved in attending to the features of stimuli. While the parietal cortex gives us the heads-up to direct our attention that something is coming, the temporal cortex allows you to identify more about what that something is—its color, shape, sound and other features. You focus on a particular detail, like the pitch and volume of the siren or other salient information, such as a bright, flashing red light.

All of this information is processed, refined and integrated with memories of relevant prior experiences as the nerve cell messages move forward through your brain, taking information to the “control nodes” of attention in the front of the brain, the prefrontal cortex (PFC)—the area responsible for our actions and responses to this information. The PFC is considered a “control node” for attentional processes—a critical gatekeeper of attention. This should not be surprising, considering its key role in the management of emotion, as we discussed in the previous chapter. Its function is to help us sustain attention over longer periods of time, as we continue to receive and consider information coming in to us (and plan to start actually doing something about it). The PFC helps us to block out irrelevant stimuli—the cell-phone conversation going on next to you when you first noticed the fire engine or the people walking across the street. While attention begins with orientation and continues with sustained focus, it also depends on our ability to handle distractions that could disrupt us along the way. As we will discuss in the upcoming chapters, the PFC is involved in more complex aspects of attention and organization—including the ability to shift attention from one thing to another and to use memory to keep attention on something, even when it’s out of sight.

Of course, in the case of the fire engine, what we have just described is the process and the mechanisms of attention working perfectly, the PFC and other parts of the brain fully engaged and the stimulus powerful and striking.

That’s not always the case.

CASE STUDY: THE LIMITS OF ATTENTION

Nancy was in her thirties, a certified financial planner and an up-and-coming star with a local financial firm. But she had a problem.

“I can’t seem to get things done. I can’t focus on anything. I’m scattered. I’m all over the place,” she said, as she sat in my office.

But she had a good job and told me that she’s recently been promoted. Surely, she must be doing something right, no? “Yeah, they’re happy with me at this firm,” she admitted. “But the more responsibility I’m given, the more I’m struggling to keep up. I’m afraid I’m going to blow it.”

Because your environment and changes in your environment can affect your ability to sustain attention, I probed her about her job and her workplace. She told me that in addition to her time on the computer or on the phone with customers, her office door was always open, and people were often dropping in with questions. She’s also frequently summoned into meetings. Clearly, she’s in a busy, potentially distracting situation. Also, it appears as if the level of work, and hence the level of attention and focus required of her, has grown. It could very well be that she’s reached her limits.

“Is this something you’ve noticed for a long time...these problems you’re having with focus?”

“Not really,” she said, although there have been times, here and there. “In my last job,” she said, “I was put in charge of this special project. I suddenly had all this extra responsibility and got so overwhelmed...,” she stops and giggles. “One time, I was supposed to show up at a meeting at 5:00 pm, I totally got distracted and went out for drinks and dinner with a friend instead.” She looked at me and smiled. “At least it was a good dinner!”

The majority of patients who walk into my office have a clear lifelong pattern of persistent, problematic symptoms of ADHD. The rest are somewhere along the spectrum from “healthy” to ADHD; with symptoms of inattention and disorganization, to varying degrees, for limited periods of times, a diagnosis of ADHD is not made. Nancy doesn’t seem to have ongoing, lifelong problems with attention but, rather, sporadic ones at various times in her life. It appears that now is one of those times.

“Do you feel like you’ve hit your capacity?” I asked her. She furrowed her brow. “My capacity?”

“Yup,” I said. “Sounds like this is a time in your life when “you have reached a certain point, when there is more asked of you, more information for you to focus on, more distractions...like you have reached your attentional limit.”

“That’s interesting,” she said. “I didn’t know that your ability to pay attention even had a limit.”

A FINITE RESOURCE

Despite all of the brain’s impressive attention hardware, there is indeed a limit to what it can deal with and for what duration. How long is a “normal” attention span? The “healthy” adult population can feel confident that their focus can be maintained for upward of an hour—about four times as long as the ten to fifteen minutes people with ADHD often cite as their typical attention span. That is, unless there is an impending deadline, significant pressure from a boss or a spouse or a task that is particularly novel or interesting. In those situations people with ADHD can focus for longer periods of time. But typically, for people with ADHD, instead of focusing on the task at hand, within minutes they are out of their seats, getting a drink of water, looking out the window or surfing the web.

Their basic unit of attention is very brief and has always been very brief, since early childhood.

What affects this length of time? Many factors. Not surprisingly, we tend to pay closer attention to that which is interesting or perceived as relevant and important to our goals or when there are some particularly striking factors related to it. So the meeting with the financial planner about your nest egg; the fast-paced, page-turning novel by the author you love; or the fire engine with the siren screaming, horn blaring and lights flashing are all more likely to be winners in the ongoing battle for your attention. These things are “salient.”

Some people’s abilities to block out extraneous stimuli and concentrate are legendary: It was said that Ulysses Grant, the famous Civil War general (and later president) had an almost “superhuman” ability to stay focused, even in the din of battle. Cannons roared, smoke filled the air, chaos reigned, and Grant was still able to focus fully on reports from the field and make key decisions. Historian and author Mark Perry called this the general’s “most sterling quality. While not the tallest, or strongest, or brightest or even the most insightful of men or generals, Grant brought a singular concentration to everything he did.” Grant’s remarkable attention powers paid off at the end of his life. Racing against a case of terminal throat cancer, he attempted to finish his memoir in order to obtain for his wife and children the profits of his book, which would resuscitate his family’s financial situation. Despite great physical pain and discomfort, he paid full attention to the writing and revisions of the book. He finished on July 19, 1885—and died four days later. Now that’s focus. A year later, his widow received a check for royalties totaling $200,000.

On the flip side, we have someone like Nancy. Normally, she was probably able to pay attention to her work for thirty or sixty minutes or even more. But when the workload increased suddenly and she was being forced to process and deal with greater amounts of information, the “wheels” of attentional progress screeched to a halt.

Sometimes, if we are not fully allocating and using our attentional capacities (as we might with the fire engine, the good book or the important financial meeting), then the information might as well not be there at all. Perhaps you’ve had the experience of a colleague saying, “I sent you that memo the other day; don’t you remember?” or your spouse insisting that “I showed you where the spare key was; you must have forgotten.” You’re dumbfounded because you honestly don’t remember ever seeing the memo or the key. It’s as if these things never happened. What did happen is that we didn’t pay attention; we weren’t processing that information when we were told or when the memo or key was shown to us. The act of paying attention is not always an automatic process. Without our concerted efforts to do so, events, information and experiences can pass us by. It’s intriguing to think that “I can’t remember” may really mean “I wasn’t paying attention in the first place.”

ATTENTION! ATTENTION!

We’ve been talking about attention as if it’s one pure substance or quality. Actually, scientists describe two types or modes of attention—goal directed or stimulus driven.

Goal-directed attention is driven from within, voluntarily by our goals and aspirations. This form of attention is consistent with our own unique life, our specific interests or aims of the moment. This form of attention is “top down,” meaning that it is rooted in those cortical areas of the brain; the ones that, as we discussed in the previous chapter, are associated with cognitive control. For Nancy, her goal-directed attention can be “on” when she is in the midst of paperwork developed for an individual client, which she sees as critical to foster an emerging customer base in a well-to-do suburb.

Stimulus-driven attention, on the other hand, can be captured by someone yelling fire, a pop-up screen on your computer, a flash of lightning on the horizon or the sound of a power chord on a guitar. Sometimes that information can be life-saving; oftentimes, it is innocuous and arbitrary. This stimulus-driven mode of attention is sensory and external. This may be what is getting in Nancy’s way—the external random people and demands that bombard her during the day through her open door.

Scientists continue to debate what makes a stimulus more likely to capture our attention. Perhaps it is the salience—prominence or relevance—of the stimuli or some feature of the stimulus itself, like its sudden appearance? Despite our evolutionary advances, maybe it’s still just “shiny metal objects” that grab our attention—as easily as a dangling string attracts the attention of a cat.

Advertisers, who have long studied attention for obvious reasons, understand this well. And some of the most successful ad campaigns are those with messages that are salient to their audience—not just gimmicky commercials that get our attention briefly. One classic example is the early 1980s ad for the Apple Macintosh, with the tagline “The Computer for the Rest of Us”—a line designed to get the attention of many American consumers who were curious about personal computers and what they could do but still felt that these mysterious machines were comprehensible only to those in white lab coats, who held advanced engineering degrees. That campaign helped launch what has become one of the most ubiquitous, successful brands in the world because its message was simple and salient enough to capture attention.

Fortunately, the brain is remarkable in its ability to manage different and competing modes of attention—some of it goal-directed information, which is consistent with our objectives, and some of it stimulus driven, which may run counter to or even change our goals. The optimal balance may be to maintain and develop attentional goals and to allow oneself to be “captured” by only those stimuli that align with our goal at hand.

Consider yourself at a work meeting. While your attention rests on one thing (the speaker at the head of the conference table), your brain continues to evaluate new information (the rustle of papers to your left, the whispered comment to your right) even at a subconscious level. These new stimuli are competing for your attention, but the organized brain is able to evaluate and screen out what is not worthy of your attention. There is still cognitive work to be done: the ability to properly handle all the noise from the environment and evaluate and prioritize it while not being pulled off the main task at hand (listening to the speaker and taking notes) is a basic and important sign of the organized brain. It’s one most of us take for granted. For some, however, that’s not so easy.

CASE STUDY: SYSTEMATIC DISTRACTION

Jason was a junior in college, and he was struggling. Distracted from his studies, he had watched his GPA plummet. By the time he came to see me, he was in danger of falling below 2.5, jeopardizing his chances to get into an MBA program, which is what he wanted and what his parents were willing to pay for—provided he could get in. “I have one semester to turn it around,” he said when he sat down in my office.

“What kind of school are you in?”

He looked quizzical. “What do you mean?”

“Are you at a big university where you have lecture halls with 100 people...or a small school with seminars of five or six gathered around a table? Are you living in a dorm in the center of campus or an apartment off campus?”

All of this was important. We needed to lay out his environment. Turns out, he was in a midsize school in the Boston area and lived in a dorm.

“So where do you study?” I asked.

“The library,” he replied. “I’m there for hours sometimes.”

“Do you get a lot done?”

“Well...not so much,” Jason said as he shifted uneasily in his seat. He told me that, while in the library, he jumps from one assignment to another, taking book after book out of his backpack. He opens them, reviews his notes or reads a page or two and then closes them and puts them away. He watches people walk by. He gets up and rummages through the shelves. He reads the notices on the bulletin boards.

Unable to accomplish much there, he leaves and goes back to the dorm. It happens to be a dorm for upperclassmen, and generally, he told me, it’s quiet. “Too quiet,” he said. “It almost distracts me. And if there’s any noise somewhere...somebody slams a door upstairs or something...it sounds much louder and really throws me off.” Eventually, he said, “I just realize I’ve been doodling for an hour.”

In addition, and this is important for the evaluation, I learned that Jason had similar issues when he was younger. Talking about his inability to keep his “nose in a book,” even at the library, he chuckled as he recalls his first-grade teacher admonishing him during their reading and writing exercises to keep his eyes on his paper. In middle school, he admitted, his attention wavered as well; in high school, although he did extremely well in some of the classes that he liked, he nearly failed chemistry. “I just wasn’t into it,” he said. “I’d find myself watching stuff bubble in the lab or reading the charts up on the wall. I think the teacher passed me, as a favor.”

Although I am confident that we can help him, by the end of our session my diagnosis is made: Jason has ADHD.

THE SCIENCE OF INATTENTION

The people I see with ADHD, like Jason, struggle with the fundamental skill of attention. The name of his condition, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, has changed over time but reflects a fundamental difficulty with the basic unit of attention. In upcoming chapters, we will see that “attention deficits” can be more than just a struggle to pay attention but a struggle to turn attention off as well. Contrary to the popular image, children with ADHD, for example, can spend hours of intense focus on a video game. It’s almost as hard for them sometimes to turn that attention off as it is to keep their attention on their schoolwork. Attentional abilities are not just an “on/off” switch. It’s about turning attention to the right task at the right time—and then to turn attention off again, when necessary, and in line with our goals.

Studies of individuals with ADHD have found abnormalities in the brain areas that are responsible for our ability to pay attention, including some of the cortical regions we’ve already discussed such as the PFC. In comparison to persons without ADHD, the brain regions of those affected by the disorder can actually be different in size, in function and in how they are wired or connected to the rest of the brain.

The neuroscience of attentional deficits in ADHD, as well as in other conditions such as stroke or traumatic brain injury, allows scientists to understand more about the working brain. While we marvel at the remarkable ability of the brain to adapt to the modern, ever-demanding world, the study of persons with medical conditions like ADHD remind us that the attentional system can be thrown into imbalance. So while the chances are you don’t have ADHD, your inability to focus and seeming lack of attention could very well be real and not a figment of your imagination. As we have seen, we do have limits. Fortunately, while that doesn’t mean there’s something “wrong” with your brain, you are correct in—pardon the pun—paying attention to your inability to do just that. The good news is that there are ways that we can resharpen our attentional abilities, better manage our cognitive load and pull back from the limits we’ve reached.

ATTENTION! YOUR BRAIN IS UNDER AN INFORMATION ASSAULT!

The human brain is facing a technologically driven onslaught of information. The advances in brain science over the past ten years have revealed that the brain is a breathtakingly complex organism. It is perfectly capable of paying attention today—and tomorrow. Nowhere is the brain’s sophistication more evident than in our attentional abilities—where stimuli and stored information, involving all the senses, are synthesized and interpreted by our brains in seconds. That, of course, is not to dismiss the increasingly complex and information-rich environment that our brains must contend with every day. As noted, attention has its limits; there are times when we may feel overmatched by the speed and volume of all that noise, which is why you may be reading this book. But just as our ancestors’ brains had to adapt to new technologies that challenged their ways of thinking—from writing and language to the operation of machines and automobiles—so will we. Trust me, our brains are not going to break down under the strain of one trying to figure out how to work a new handheld device or respond to one more Facebook post.

What research is now telling us is that what “hooks” our attention is usually something consistent with our goals. That’s more important than how “loud” or salient the stimulus is. We can process a lot of information about that fire engine, attend to it briefly and then get back on task. But if your cell phone vibrates and you see that it’s your spouse, your boss or your physician, well, you’re cognitively adept enough to block out the sirens and flashing lights and hook your attention to the phone call, the stimulus that really matters to you. The implication here for someone struggling to stay focused is that we need to foster as much goal-directed attention as we can. We need to be more discriminating and not just go chasing every fire engine—no matter how shiny—that comes racing down our street.

That, we can learn to do.

COACH MEG’S TIPS

Many of us have early memories of our schoolteachers chiding us to “pay attention!” We discovered at some point that we were good at paying attention to people and things that were engaging and fun, and we struggled with people and things that were boring or uninteresting. Our parents and caregivers diligently watched for the activities that grabbed and sustained our attention, signs of our individual talents and interests.

As we grew up and got into the full swing of adult life, we found ourselves with such a long list of things to pay attention to that it was easy to lose our sense of our innate abilities to pay attention and our unique preferences of activities and people to pay attention to. Recall the early stages of romance when your sweetie commanded your attention beyond anything else. Remember your best memories and how completely absorbed you were in the moment and place. Your ability to pay attention may be lost but not gone.

The ideal state of attention is called “flow,” characterized and studied by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (pronounced Cheek-sent-me-hi) for thirty years as a professor at the University of Chicago. “Flow,” he wrote, “is the experience people have when they are completely immersed in an activity for its own sake, stretching body and mind to the limit in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.” The term is used by many people to desc22222ribe the sense of effortless action they feel in moments that stand out as the best in their lives. Athletes refer to it as “being in the zone.” The more flow experiences we have in life, the happier and more fulfilled we are. Paying attention fosters well-being.

Inhisbook, Flow: ThePsychologyofOptimalExperience, Csikszentmihalyi tells the story of a woman with severe schizophrenia in a mental hospital. Her medical team had failed to help her improve. The team decided to follow Csikszentmihalyi’s protocol to identify activities where she was motivated, engaged and felt better. A timer went off throughout her day, signaling her to complete a minisurvey on her mood, energy, engagement and so on. Her report showed that her best experience was trimming and polishing her fingernails. So the medical team arranged for her to be trained as a manicurist. She began to offer manicures at the hospital and eventually became well enough to be discharged. She went on to live an independent life as a manicurist. This is the power of paying attention to activities we love to do for their own sake.

It turns out that many of us have most of our opportunities for flow-producing experiences at work, yet we miss out on their pleasure because they are polluted by frenzy (a long to-do list, etc.) or by countless other unnecessary stresses and strains produced inadvertently by most corporate cultures. Sustained attention and flow is a natural state, so rest assured that it is something you can have more of with a little forethought and planning. How can you live a life with more focus, sustained attention and increased flow?

Take an inventory of the times when you’re naturally at peak attention

Just as you did with your moments of frenzy, it’s important to recognize patterns in your life. Think about your life activities that feel absorbing and effortless and make time fly by and that when you’re done, you are energized by a sense of accomplishment. These are times when you are not struggling and when your abilities are stretched slightly by the challenge, enough so that you are fully engaged and interested. Too much of a challenge makes you feel out of control and too little leaves you bored. You are likely applying your strengths liberally, whether you’re good at facilitating meetings, playing tennis or the piano, cooking a new recipe or writing a blog. As Dr. Hammerness noted, the research shows us that goal-directed attention is the type that we are most likely to sustain because it is more meaningful to us. Let’s make sure we can identify the activities in our life that engage us in that manner.

Do more and harvest more from natural attention-producing activities

Expand your awareness and gratitude for these wonderful moments of flow described in the previous section. Make them even more special by ensuring that they are “clean” experiences, not polluted by frenzy. So close the door, turn off your cell phone and e-mail, and engage and enjoy the activity fully—and with a spirit of adventure, curiosity and discovery. Experiencing these natural attention-producing (or goal-directed) activities—the things that you love to do—in this kind of pure way will show you that there is nothing inherently wrong with your ability to be attentive and that your attention is optimal when the activity is interesting, engaging, uses your strengths and gives you energy and satisfaction.

Initiate moments of mindful attention

Now that you have connected with your many moments of peak attention—and the possibility of many more—start thinking about awakening from chronic frenzy and mindlessness and creating more moments of peak attention. Being present and mindful, enjoying the shower when you’re in the shower, appreciating the aroma of freshly brewed coffee and basking in your child’s innocent smile are all starting points. Pay attention to the moment. Take a breath and notice where you are, how you feel, your surroundings, and just be. The skill isn’t far from grasp—you had it in spades as a child, with a mind clear of years of clutter, thoughts, emotions and memories. Dig it out and try it on, like a new outfit, every day. Just be for a short while. Not do.

The more mindful you become, the easier it will be to initiate your attention and be in charge of your attention rather than allowing it to be out of control.

Explore and apply your strengths: unrealized opportunities for sustained attention

An important lesson from flow research is that we are more interested, engaged and energized when we are using our strengths, while engaging our weaknesses drains our energy, which makes it hard to sustain attention. Other research shows that fewer than one-third of adults have a good understanding of their strengths. So learn about your natural talents and strengths you’ve cultivated over time. Fortunately, as mentioned earlier, there are many assessments of strengths: VIA Survey of Character at www.viacharacter.org, Clifton StrengthsFinder at www.strengthsfinder.com or Strengths 2020 at www.strengths2020.com. Find a coach or buddy to help you think about your strengths and how you can use them more so that they are at your fingertips when you want to initiate your attention. When I recall that one of my strengths is persistence, it helps me reignite my attention when I am tired or drained. I’m good at persisting when it isn’t easy—bring it on.

Convert moments and activities into flow experiences

You can make any moment or activity flow producing or attention sustaining by applying the ingredients that, as Csikszentmihalyi has taught us, can lead to flow.

First identify a goal-producing activity: “Tonight, I will find time to focus completely on my son’s state of being...not to nag him about things he needs to do but to check in with him and see how he’s doing.”

Set a goal for the activity: “I will give my son my undivided attention for ten minutes; I will make sure that I listen and resist the temptation to jump in and tell him what I think he should do. I will validate the positive things that he chooses to talk about and emphathize with the tough stuff. I will make him feel respected, loved and listened to.”

Look for signs of progress: “As we talk, I’ll look to see that my son moves from beyond “yeah,” “okay,” “whatever,” and other typical monosyllabic responses to questions about how his day went, to complete sentences as he realizes that I am listening. I will look for him to smile, laugh, relax and hopefully hug me warmly at the end.”

Harvest the result: “I will thank my son for sharing his day’s experiences with me; I will offer myself as a resource and sounding board for him anytime in the future. I will enjoy and appreciate the connection we have made during these ten minutes and feel good that it has strengthened our bond as parent and child.”

Recharge your brain

Our brain is like our muscles: when we use it too much, it gets tired and needs a rest. After intense periods of focused attention, no more than ninety minutes, take a brain break—take a few deep breaths or get out of your chair and change scenery. If you’ve been in front of the computer, some gentle stretching or a short walk will do wonders for your body, not to mention your brain.

Pay attention to small activities

Much of the above discussion has focused on longer activities because that’s where we get traction and make forward progress in our lives, building our families, friendships, careers and well-being. That’s what builds our satisfaction with life over time, like a foundation of well-being to stand upon that grows with life experience.

Paying attention matters in the smaller moments in everyday life, too: driving to work, short conversations by phone, clearing a few e-mails, cooking a quick meal, folding laundry. Pay attention and appreciate how full small moments can be. Find the special in the ordinary. That “stop and smell the roses” advice we’ve always heard may sound trite, but there’s truth there.

It’s harder to be mindful when we’re swimming in a soup of negative frenzy. Yet negative moments are part of being human and deserve our full attention. Don’t distract yourself totally from the negative. It is often said that we learn more from our failures, disappointments or setbacks, provided that we are receptive to the lesson.

Here are some examples of how you can find the silver lining:

Your flight is delayed, and now you’re stuck for two extra hours in the airport.

Use the time productively: read a little more of your book or use this opportunity to crack open a new book you’ve wanted to start but didn’t have time for. Or perhaps you didn’t have time this morning to exercise—well, you can use this time to walk around the terminal or do some yoga in the meditation space in the airport lounge.

You have a fight with a colleague over responsibility on a project.

How can you use this to build a better relationship with this person? Perhaps this is an opportunity to restructure some of the ways things are done at your workplace. Maybe you can work together to present to the boss a new plan of doing things?

Your spouse is ill, and for the next few weeks, you will have to take over his or her responsibilities.

This is a way to better appreciate your spouse’s contributions in your life but also to challenge yourself. Now you’ll be paying the bills... or doing the laundry...or fixing the meals for a while. These are new and valuable domestic skills to acquire.

You missed an important project deadline.

It could be something like this that prompted you to pick up a book like this in the first place! This is a wake-up call to you—you need to get better organized and on top of things, which you are now well into the process of doing.

Learn how to handle distractions

While we can minimize distractions by closing the door, working in a quiet room and turning off the cell phone and computers, distractions will arrive despite our best efforts. First, listen to your needs: perhaps you are presently easily distracted because you’re tired or overworked or you are not in a mindful place or the task before you has been badly designed to be boring or anxiety producing. Your susceptibility to distraction is a sign to pay attention to. What is it telling you?

Mindful attention works beautifully when a distraction arrives, knocking at your door demanding your attention. It allows you to make a conscious choice in the moment without creating frenzy—choosing to switch attention to something new or choosing to notice it and then tune it out. Getting control of one’s choice of response is the real lesson here. You’re in charge of your attention; you make the choice to follow the temptation of distraction. Get into the driver’s seat.

The story about the television star’s illicit romance pops up on the computer screen—do you really have to read that now?

You receive a call from your friend wanting to chat or the drop-in visit from a colleague who wants to gossip—can you politely tell them when they ask the perfunctory “Got a minute?” question that no you don’t, but you would like to talk with them, and you’ll get back in touch in a little while?

It’s really not that hard to say “no” to distraction.

Train your mind

It may be that your brain has become wired into a state of frenzy and chronic distraction and, like a muscle group, needs some training to find the old wiring for your capacity to focus. Learning how to meditate is all about learning to pay attention to the present moment and may be one of the best investments you can make. Or coach yourself by setting goals for paying attention, and pair up with a buddy for accountability. How focused were you today? Rate yourself between 1 and 10. Focus on increasing your score slowly and surely over time.

Let your mind wander!

As Dr. Hammerness described in the first part of this chapter, attention is an innate, human ability to be tapped into and optimized. It’s not like learning to walk but rather a skill that can be sharpened. Being attentive is critical to your becoming more organized, but let’s not forget that there are times when it’s good to be distracted, to let your mind wander. You can and should practice and work to become more attentive in many situations of your life—but not all. Make sure you do take time to turn off the switch once in a while. Enjoy the random thoughts and shiny objects.