The Man Who Talked To Bees

Amazing Stories – July 1955

Randall Garrett

(as by Ivar Jorgensen)

Take a lonely man with too much time on his hands and an acute dislike for people, give him a volume containing the mystic knowledge of Hindu fakirs, and trouble will buzz around your head like a cloud of bees. But trouble, like a sword, cuts two ways!

-

HE CAME upon the phenomenon quite by accident. A man of inquisitive mind, he was forever investigating alien byways, and had accumulated quite a lot of completely useless knowledge; that is, if any knowledge can be classified as useless.

-

He knew how a gasoline motor worked although he was not a mechanic; he knew more about Einstein's theory than most persons of average mind; he was well up in the care and feeding of tropical fish, though they were not his hobby; he could cast a horoscope and discuss it intelligently, even though he had no belief in the potency of the stars.

His probable reason for burrowing like a mole—he actually looked a little like one—through mountains of factual data, was because of his loneliness. And he was lonely because he refused to allow people to get close to him. The cross he bore was one of meanness, resentment, jealousy, sullenness. He liked no one because he was continuously measuring the virtues and abilities of those he met against his own weaknesses and shortcomings. As a result, people instinctively disliked him and avoided him. As they did so, he snarled at them from the door of his emotional doghouse and—except in the cases which developed into actual hatred—forgot them. He was a beekeeper by trade, knew the business inside and out, and told himself he was far happier with bees than with humans.

His active hatreds were highly poisonous, as they would be in a man of his type. At the moment, he was engaged in hating Colonel Winthrop who had moved into the house at the end of the lake and had come calling about a month before.

"I saw your name on a comb of honey I got at the village store, Mr. Parsons," the Colonel said, "and I was surprised to see it again on your mail box. Bees always interested me, so I thought I'd drop over and get acquainted."

Sam Parsons was civil enough; he even showed his visitor around, but it didn't take him long to see what kind of a man the Colonel really was; a snob wearing a cloak of affability; an aristocrat who loved to come down the hill and lord it over the peasants under the guise of democracy. Oh, Sam Parsons had an eye for character all right, but his analytical record was unique in that he'd never discovered an admirable person.

In less than ten minutes he had hated the Colonel cordially. After three or four visits, he'd have loved to see the man dead.

The new phenomenon he stumbled onto, stemmed from a book he picked up in a local bookstore. The title interested him—The Principles And Practice Of Yoga. He'd never given the occult much attention. Might take the boredom out of a few evenings. He bought the book and started through it that very night.

He was surprised at the clear, concise style of the writer—some Indian with a name beyond all comprehension—and was impressed by the fact that the man offered the neophyte no rewards for mere reading carefully. He wrote of rewards—physical and mental betterments, heightened abilities, supreme peace of mind—but his key to this treasure chest was work, drudgery, determination. The Indian stated with complete frankness, that ninety-nine people out of a hundred would get no benefit whatever from the book and would be wasting their time.

Sam Parsons accepted this as a challenge; a slur against his determination which was the kind reserved for only those capable of hating doggedly, unreasoningly, and wholeheartedly.

The book was in two sections—the principles, and the practice thereof. There were physical and mental exercises clearly set forth; types of breathing; difficult and painful physical posturing; ways of forcing disciplinary concentration upon the mind, the theory being that the average person used only ten percent of his brain power and these efforts would whip the other ninety percent into action.

Sam worked doggedly, grimly, and the Indian with the big name never knew that he was on trial. Sam determined to do his part, and if the promised results were not forthcoming, that Indian was going to be the most cordially hated individual ever born of woman. He was going to be hated by an expert.

But Sam began getting results. He felt better. The small aches and pains that plague the reasonably healthy fifty-year-old body, left him for a physical exhilaration he had never known before. There was new spring in his legs and now the climb to the hives up on the knoll left no weariness in his legs.

But the physical betterment he experienced was secondary to the mental improvements. His mind was sharper and more penetrating than it had ever been before; a broader, more encompassing sense of awareness seemed to be his. His senses sharpened and there was no weariness no matter how much he used his mind.

And his hatred for Colonel Winthrop brightened to the point where the pleasure he derived from it was almost a tangible thing.

Relative to concentration, Sam got to the point where he could sit motionless for two full hours with his mind centered upon a single thought.

Then came the tremendous revelation of power.

-

He was seated in motionless concentration one afternoon, when a fly circled casually into the room. Just as Sam finished his two-hour session, the fly alighted on the arm of his chair. Sam's mind pounced on the fly like a hawk on a chicken. In a burst of sublime foolhardiness, his mind said to the fly: I can control you. My mental powers are stronger than yours.

Sam had assumed, of course, that a fly has mental powers. He had no proof thereof. Neither did he have any real belief in his ability to control the fly, his thought being a mere gesture of mental exhilaration.

The fly sat motionless for a moment. Then it spiraled into the air and settled on the ceiling. Sam's eyes followed it. His mind ordered: Come back. Come back and sit exactly where you were before. When the fly obeyed, Sam—still the level-headed fact-finder—charged it to coincidence. It could be nothing else. He looked at the fly. The fly was apparently looking at him. Sam's mind ordered: Go over and sit on the third button of the jacket hanging by the door. Then come back.

The fly went over and buzzed around the jacket, selected the third button, sat upon it for perhaps five seconds, then returned.

There were suddenly two forces fighting within Sam Parsons: his common sense, and an unreasoning conviction that his new-found power was indeed the McCoy. The fly had done exactly as directed. Twice. That eliminated coincidence. The percentages against subconsciously predicting the fly's exact movements twice in succession were astronomical.

It also seemed beyond all reason to assume that a fly could count to three.

Sam formulated another order: Go over and stand on the doorknob.

And it was then that a new phase of the thing developed.

From somewhere in the ultrahigh frequencies in which Sam's mind had been lifted, there came a thought wave that was translated by his brain into a single word. The word registered in his highly sensitized consciousness: Why?

Sam stared. And again came this concrete proof of a statement made long ago by a very wise man: There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio—

Why should I go over and sit on your doorknob?

Sam Parsons could reject the obvious no longer. He had achieved rapport with the mind of the fly! Its mental processes, however feeble and elemental, had been contacted, and translated into a symbol his own consciousness could understand.

Sam trembled and almost allowed his concentration to shatter into a million thought waves. Then he caught himself and replied mentally: Because I tell you to.

The fly seemed to be thinking it over. Then a vibration came back to Sam—a sullen, rather grumpy one, he thought: Oh, all right. And the fly went over and alighted on the doorknob.

Sam made three more tests, proved the thing conclusively. Then he released the fly and slumped back into his chair, every muscle weary, perspiration pouring from his body. He sat thus for many minutes and then allowed himself a bit of recreation after all the hard words—some dessert after a meal of tough meat.

He gave his complete attention to hating Colonel Winthrop.

-

It was about three weeks later. The Colonel's phone rang. He was rather surprised to hear the voice of that strange little beggar up the lake; that odd one that kept bees; Parsons—yes, Sam Parsons—that was his name.

Parsons said, "I stumbled onto a little thing, Colonel. Thought you might like to drop around to my place and see it."

Parson's voice was so cheerful as to completely bewilder the Colonel. "Why, ah—yes-yes, certainly. I'd be glad to."

"This afternoon?"

"Yes, I'll come by."

As he walked on the rough lake road some hours later, the affable Colonel decided he must have been wrong about Parsons. Strange, though. He'd called on the man three or four times just to make sure his first impression had not been erroneous; had verified the fact that Parsons was a nasty little bore. No other term described him. Seemed to carry a permanent chip on his shoulder. The Colonel prided himself upon being a genial, fair-minded person, not easily riled. But upon the last visit, he'd been forced to tell Parsons what he thought of him—did it in self-defense, really. The little bounder had asked for it again and again.

But the Colonel was the sort of man who never held a grudge and felt sure Parsons wished to apologize. This in itself, was enough to make him accept the invitation. He always met people halfway.

Parsons was waiting at the front door; waiting with a big smile. That alone was a vast improvement over the last visit. He said, "Come in, Colonel, come in. Of course, my place isn't as large and imposing as yours, but—"

Colonel Winthrop frowned. "Good lord, man! What's that got to do with it?"

"Nothing—nothing at all. Sorry I brought it up. Won't you sit down?"

"Thank you."

Parsons sat opposite his guest with a smug look on his face. He got right down to business. "Colonel, do you see that fly?"

The Colonel followed Parson's indication. "There on the table? Why, yes. Ordinary house fly. Quite commonplace."

"No, there is something different about this one. He hates you very much."

"Now reallv, man—"

"It's a fact. Watch."

Parsons stared at the fly. He said, "I've developed a method of talking to insects, and I've told this one the truth—that you have only contempt for it—that you'd smash it with a swatter if you had the opportunity."

The Colonel was sure Parsons had lost his mind, but he had little time to ponder this because the fly's actions were fascinating. The insect spiraled up into the air and hung poised for a moment, buzzing angrily. Then it dive-bombed the Colonel. No other term covered the act. The insect did two loops and then shot straight down at the Colonel's nose. It struck, veered away, and then repeated the maneuver until it tickled the Colonel into a lusty sneeze. This disconcerted the fly. It shot up and hung near the ceiling, buzzing ominously.

-

The Colonel jumped to his feet. "This is monstrous, Parsons! I simply won't stand for it!"

"Sit down, Colonel. There is more."

"More?"

"Yes. You see—I plan to kill you."

The Colonel dropped back into his chair and gaped at his host. "Parsons! For heaven's sake! Why on earth would you want to—?"

"You're like all the rest, Winthrop. You think that a man must have a strong, emotional motive in order to kill. That's not true. Everyone would kill at one time or another if they could do it safely. My reason for eliminating you isn't earth-shaking at all. I merely hate you. You disgust me. I want to see you dead and I have the means. You see, I've learned to control insects, as I'm sure I told you—"

"Absurd!"

Parsons ignored the Colonel's doubt. "But more important, I've found a way to enlighten them. You see, flies, for instance, are not antagonistic to humans because they don't know humans hate them until they are swatted, and then it's too late. The reason that fly up there hates you is because I told him exactly what you think of him. He resents it. He too, would like to see you dead."

The Colonel fell back on dignity. "I refuse to stay here and—"

"One more point that will interest you," Parsons said. "At first I could talk to only one insect. But I applied myself—broadened the power—and now I'm able to sway any number at once."

Colonel Winthrop had regained control of himself. He got to his feet and spoke sternly. "I'm going straight to the authorities, Parsons. You are mentally sick and you need help. It's my duty to see that you get it. I'm sure the psychiatric chaps can straighten you out." He opened the door and walked out of the house.

Parson's made no attempt to stop him; and when the Colonel got to the road, he breathed a relieved sigh. You couldn't always tell about these flighty characters. A man off his beam could do anything. Might even have a gun on the premises. The Colonel hurried down the road. He'd go home and get his car and drive to the village immediately.

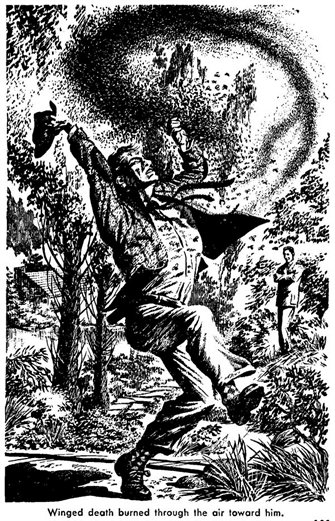

He had gone scarcely fifty feet when there was a sharp, whining sound. The Colonel threw up a quick hand and just missed the insect that zoomed past his left ear. It veered sharply into his face and he struck out again. A pesky honey bee.

The bee's motor revved up. It did an Immelman and came in again. A positively maniacal insect, the Colonel thought as he slapped at it. The bee avoided his clumsy swing, drove in, and the Colonel felt a sting on his right cheek.

And now came a second bee, a third, a fourth. The Colonel flailed wildly and looked about for shelter. There was none, but as his eyes came around, he saw a dark, hazy line streaming down from Parson's knoll. Bees. Thousands of them. Winging straight in his direction. The Colonel threw up his arms to protect his head, but he was pitifully helpless as the mad swarm encircled him and he became the core of a deadly whirlwind. He screamed and began running, but the bees worked with such swift, horrible precision that they were now upon him in thick masses, crawling into his clothing, entering every available orifice of his body. There were bees in his throat, choking him.

Mercifully, the Colonel did not suffer long. The ferocity of the mass attack stunned him, shot so much venom into his body that the shock of it rendered him unconscious.

He was dead in an incredibly short time.

The remains of Colonel Winthrop lay on a table under a white sheet in. the back room of the local jail. The grave-faced coroner had just finished washing his hands. He turned to the county sheriff. "Terrible thing. Art—terrible."

The sheriff stared at the lumpy, shrouded form. "Bees. Good God! Stung to death by a swarm of bees. Ever hear of a case like it, Doc?"

The coroner pondered. "Once. A long time ago. In the town where I lived as a boy. But it was somewhat different. A man tried to take honey from a wild swarm in a tree. He wasn't adequately protected and they killed him."

"But the Colonel was walking down the road—minding his own business!"

"That's right. I said it was different."

"I never in my life heard of bees attacking like that."

"Freakish."

"What do we do?"

The coroner shrugged. "Bury him."

"I guess there's no action to be taken."

"Against Parsons, you mean?"

"Well, after all, he keeps bees. They were probably his swarm."

"No doubt. But I don't see how you could hold him on a criminal action."

"Of course not."

"The Colonel's family might sue. That's about the extent of it."

"Out of my range," the sheriff said. "If there's nothing criminal involved I just stand by."

The coroner hung his towel on its peg. "Too bad. Tragic. Nice fellow."

"One of the best. Englishman wasn't he? I mean, didn't he come over from England?"

"Uh-huh. Struck you as being a little pompous—even overbearing, until you got to know him. I had a few talks with him. His main fear was that he wouldn't be accepted. Liked people. Wanted to be liked himself."

"Who doesn't?"

-

Sam Parsons was now spending most of his time in the rarefied mental heights to which his practice of yoga had lifted him. And with no comprehension of how badly yoga had failed him—or rather, how he had failed yoga by twisting its honesty and constructiveness to his own particular viciousness. He contemplated Colonel Winthrop's terrible fate with great satisfaction; used it to magnify his sense of power. His ability to exact vengeance was infinite! As he continued to work and expand his mastery, there would be no limit to the satisfaction he could exact! He'd show them how dangerous it was to fool around with Sam Parsons!

There were minor reactions, of course; times when a small fear nagged him. What about the law of retribution? In an ordered world. Could evil be perpetrated with impunity? There were checks and balances? Could such freedom of action be tolerated?

But Sam was able to shake off these doubts by telling himself that he had transcended the law. After all, retribution in such cases as this could be brought about only through human intervention, and he was operating in a realm where human law could not touch him.

He had gone above the law! He could not be touched!

There was still a living to be made, however; hives to be stripped. He was preparing for this task a few days after the Colonel's death, when a new idea struck him. Why not use his power to increase the output of his swarms? It should be simple enough. His bees certainly weren't working at capacity. Nothing in the universe worked to capacity unless forced to do so. While thinking this over, he carried a honey case to the knoll, set it down, and opened a hive.

It was interesting to listen to the reactions of the workers. How stupid they were! He'd taken honey from them again and again. Yet they did not realize that they were being robbed. They buzzed about, talked to each other, thought in terms of honey to be gathered rather than honey to be saved.

He reached in expertly to remove the combs. Then he stopped. Not frightened. Merely interested. There was something new here. An excitement among the workers. One he could not interpret. Almost immediately, its cause became apparent to his trained eye.

The queen had emerged.

His first thought was of losing the swarm. The queen had picked this moment to leave. The swarm would of course go with her. This was annoying. A swarm was valuable and the queen might travel for miles before alighting.

Then Parsons laughed. For a moment, he had forgotten about his power. He looked at the queen; reached out toward her with his mind: Stay where you are.

So you've come.

The queen made no move to depart, which proved his power was still potent. But the reply to his order was a strange one. Perhaps it had been misinterpreted: Stay where you are.

You think you've found a loop hole?

Parsons frowned. Was this coming from the queen? Hardly possible: Go back into the hive.

You've made a mistake in your thinking. You can't go above the law because the creator of the law created you also.

Parsons felt a slight chill. Get back where you belong.

-

The queen sat motionless, staring at him. The swarm was strangely quiet: The universe functions on a basis of law and order. Action and reaction. All is governed by exact law. If a single loophole existed, then creation would function by chance. In short, it could not function. It could not even exist. Its components would tear it apart.

Parsons felt a touch of panic. This was not the queen projecting. She was not capable of such reasoning. The same philosophic facets upon which he himself had been pondering.

His fear subsided. Merely another phenomenon. Somehow, his own previous thoughts were being reflected back to him. They weren't coming from the queen at all. She was only an insect and the mind of any insect was subordinate to even the weakest human mind: Get back in your hive.

You turned my workers to a base purpose.

Parson's chill returned. That was no reflected thought of his own: Get back—

The queen did not move: Here, I am the law.

There was a stirring in the swarm. And again, the thought-voice: Did you think you could outwit the very force that created you?

And Parsons realized it was, in truth, the voice of the queen, but that it came through her rather than from her. That it welled from her authority as a part of the law he had tried to flout. That she was only a bee, but that the law was everything. That it manifested through all its agents from the tiniest microscopic life form to the planetary systems too vast to conceive. That no action could avoid its just and natural reaction.

The swarm stirred and rose. Frantically, Parsons ordered them away but it was as if he were closing an electric switch connected to no wires. They enveloped him in a hurricane of vengeance, their purpose plain.

He screamed.

-

The coroner wiped his hands grimly. "Two in a row," he said.

The sheriff stared helplessly at the lumpy, shrouded form. "What do I do? Arrest a swarm of bees?"

"Let's not be facetious. They certainly have to be eradicated."

The sheriff was offended. "Give me a little credit, Doc. I've already seen to that. Sent for a bee expert. He's on his way up here to gas them."

* * *

But from some strange source, wisdom was given the queen, who passed it on to the other hives. When the expert arrived, the boxes were empty.

The End