One morning, we had an important appointment with HIAS. Before we left the hotel, my father insisted my two brothers join him in reciting the morning prayers. Both refused. “Sali, sali” (Pray, pray), he kept screaming at them, as Mom, Suzette, and I watched, paralyzed. By the time my brothers joined him and read—sullenly and by rote—more than an hour had passed, and we missed the meeting. HIAS officials were furious. If it ever happened again, they warned, we would be immediately cut off from any assistance.

Immigrating to the United States had turned into an ordeal, a painful, drawn-out process filled with bureaucratic land mines. While Israel, which took in all Jewish families, would have welcomed us, we had to persuade HIAS officials that we, in effect, deserved to live in America.

From the start, it was my father’s job to engineer our entry.

French society was intensely patriarchal and accorded husbands and fathers an inordinate say in a family’s affairs. We trooped along with him when he was asked to report to HIAS offices on rue Lota in the tony sixteenth arrondissement. We found ourselves in a neighborhood of vast, expensive tree-lined streets with private mansions and residential buildings set back behind tall gates. None of us said a word as we walked. We felt small and lost and thousands of miles removed from the grittiness of Montmartre and the rue du Faubourg Poissonnière.

This was the Paris, elegant and graceful, that we had expected to find when we’d left Egypt, the city Mom and I glimpsed when we went to Parc Monceau. But as with our visits there, we were being granted only an evanescent glance before being forced to turn back to our dilapidated quarters.

At HIAS, we were met by social workers who overwhelmed us with forms to fill out and barraged us with questions. Why were we so intent on moving to New York? they’d ask us again and again. Why had we left Egypt?

As if they didn’t know.

My father told of the anti-Jewish sentiments we had witnessed toward the end, the fact that one by one all our relatives and friends had left, and even he, who felt an abiding love for the city and country of his youth, had come to realize our lives were in danger.

“I could no longer provide for my family,” he told Mademoiselle Cygler, our caseworker; “my children had no future in Egypt.” Unlike Madame Dana, her counterpart at Cojasor, the HIAS social worker seemed to have taken an intense dislike to all of us; she clearly resented our inability to make up our minds, our chronic unhappiness.

By the late fall of 1963, my father’s efforts to get us approved for America had turned into a nightmare. HIAS and Cojasor seemed delighted with my older brother and sister, and were eager to let them emigrate. They were seen as exceptionally promising candidates. The problem was Dad. They were prepared to deny us all entrance because of their misgivings about him.

My father, the Cary Grant look-alike who had made beauties swoon and forced business rivals to heel, was deemed undesirable for America.

Too old, HIAS said. Too sick. Too infirm. Too beaten down. No prospects. Leon looked considerably older than he was in his weather-beaten raincoat and with the wooden cane he now relied on to walk. In the eight months since we had left Egypt, he seemed to have aged by almost as many years.

HIAS pointed out his limitations, the fact that he was so frail. It would be difficult, if not impossible, for him to find a job, they said. He would be unable to support the family, and then what would become of us?

“I worked until the day we left Egypt,” my father coolly reminded them, seemingly unperturbed by the harsh put-downs. “I will work again.”

He added: “Le bon Dieu est grand.”

He wouldn’t back down, and on that afternoon, the bureaucrats and social workers saw flashes of the indomitable will that had guided my dad through six decades, they caught a glimpse of the man of iron who had been born in one country, settled in a second, found himself exiled to a third, and was now determined—or perhaps merely resigned—to start life in a fourth.

But no matter what he said, the social workers kept reminding him of his physical limitations, the fact that he had trouble walking.

“I don’t only walk—I can run,” he cried out. And he looked as if he were suddenly going to bolt, wooden cane and all, out of the town house on the rue Lota and down the avenue Foch to the Champs-Elysées, and all the way back to…to where?

Anywhere but here, anywhere but this city that didn’t want him to stay, yet had nowhere for him to go.

His most passionate arguments fell on deaf ears. In their internal deliberations, the resettlement czars were even more blunt in expressing their misgivings. Leon would never be a productive member of American society, they told each other in aerograms and telegrams that flew back and forth across the Atlantic. We were destined to be wards of the state because Dad wouldn’t find work.

Suzette and César posed no such conundrum. They were energetic, well-spoken, healthy, and, above all, young—precisely what America wanted. All they lacked was the ability to speak the language. They had to start studying English immediately. We all had to—with the exception of my father.

Off we went to English class, with orders to learn to speak and read as rapidly as possible.

I was permitted to tag along. I was delighted: after months of feeling left out of adult decisions, I eagerly proclaimed my desire to take English lessons.

Classes, which were held close to the avenue Foch, were taught by a pretty American expatriate named Nancy Hakimian. Miss Hakimian was so perky and charming, César spent most of his time looking at her instead of paying attention to what she was teaching. My sister, always a diligent student, took careful notes. If Isaac came, I didn’t see him. Mom, who went occasionally, stared forlornly out the window.

Miss Hakimian would begin each class with a dramatic stunt designed to get our attention: holding a large white porcelain mug high up in the air.

“Cup,” she’d say.

We had to repeat after her: “Cup.”

Then, in a feat that never ceased to amaze me, no matter how often I witnessed it, the teacher would take the cup and smash it in two.

“Broken cup,” Miss Hakimian cried.

We were supposed to chant, “Broken cup,” with the emphasis on “broken.”

Those were my first English words—not “hello” or “my name is Loulou” or “good morning,” but “cup” and “broken cup.” The following session, she would begin the lesson by holding up the same cup and take us through the drill all over again.

The cup seemed to have magical regenerative powers—no matter how often it broke, it reappeared in one piece the next time.

As we advanced, Miss Hakimian expanded her repertoire of breakable objects to include saucers, plates, and glasses. She’d smash the saucer against the blackboard, fling a dish to the ground. They all made a comeback at the lesson that followed, and Miss Hakimian would smile mysteriously as if she alone knew the secret of their healing power. My English vocabulary grew to include “saucer” and “broken saucer,” “plate” and “broken plate.”

César, though beguiled by the lovely Miss Hakimian, seemed unable to grasp the most basic words or phrases. He was asked to take an aptitude test to determine what he should do when we reached New York. He was sixteen years old, and back in Cairo, he had studied to become an accountant, and hoped to go into business like Dad. The test was rigorous and took several hours to complete. In addition, he met with vocational counselors.

The verdict came in at last—César had technical skills, he was told, and was urged to pursue a career as an auto mechanic. My brother, who didn’t have the least interest in cars, who couldn’t even drive, didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

Unlike my employable siblings, Leon had no need for any English lessons. Even the bureaucrats marveled at his raffish British accent. They couldn’t help wondering how he could converse in the King’s English, while his children seemed ignorant of the most basic elements of the language. But they weren’t prepared to cut him any slack. Convinced he would take from the system rather than contribute to it, they balked at letting him come to America.

At last, an obliging French doctor helped my father overcome a crucial hurdle. He certified that in his professional opinion, Leon was both healthy and fit to hold down a job. In form after form, the amiable young physician, Docteur Sananes, testified that Leon would indeed be able to work full-time, provided the employment was “sedentary.” He downplayed the effects of Dad’s broken leg and gave an upbeat, if not exactly rousing, endorsement.

Still, any celebration would have been premature; we had no idea when we would be checking out of the Violet Hotel. The quest to find us a home in America dragged on. Even after we heard we were approved in principle to settle there, the process seemed fraught with complications. HIAS launched a desperate search for relatives in the United States who would sponsor us, employ us, support us, welcome us into their homes, help us in any way. The cables crackled as officials contacted long-lost cousins from Brooklyn all the way to San Diego.

HIAS was encouraged that one relative had already stepped up to help—my Milanese cousin Salomone. Dad’s nephew sent word he was prepared to give several hundred dollars to defray the costs of our move and had begun sending checks over to HIAS.

Our American cousins seemed to react altogether differently; admittedly, the initial requests from HIAS were ambitious. Could anyone subsidize our initial stay until we found our footing? The answer came back, a clear-cut no. Even a close family member like my mother’s half sister Rosée complained that she and her children in Brooklyn were barely making ends meet.

HIAS proceeded to ask whether these relatives would take us in, allow us to live under the same roof for some weeks or months. Again, the answer was a resounding no. There was no room in anyone’s cramped American dwelling for my family.

The agency drastically scaled back its demands. Would our relatives in New York at least help look for a suitable apartment for us? Once more, the answer came back no. My mother’s relatives said they would try, but were too busy to find us a place to live.

HIAS made one other intensely modest request. Would someone, anyone, come greet my family at the pier?

There was no reply.

News of their balkiness reached my mom, who was thoroughly wounded. She had always adored her half sister Rosée, and spoke fondly of how warm and welcoming she and her children had been back in Cairo. What had happened to make them so distant and self-absorbed—so emotionally stingy? Was that one of the dangers of becoming an American?

Perhaps that was another English lesson, one that involved not shattered dishes but familial bonds that were irrevocably broken.

WE STILL HADN’T UNPACKED by the early winter of 1963. Whatever progress the resettlement agencies were making on our behalf seemed painfully slow. My sister, in particular, despised the lowly secretarial job she had finally landed at a nearby textile shop, which was off the books. One day, she discovered she had misplaced an entire month’s salary: the money had been either lost or stolen. The episode only underscored her sense of futility.

A local furrier hired my younger brother, Isaac, now thirteen, to work with him in his small factory near the Violet Hotel. César, meanwhile, was racking up tips doing odd jobs, running errands and delivering packages for a fabrics store situated on the passage Violet. Its elderly Romanian owner developed a fondness for my oldest brother and dispatched him all over Paris to deliver bolts of the fine wool he imported from England. Generous tips made it easier for César to enjoy his nocturnal escapades with his new friends, other teenage refugees staying in nearby hotels. His greatest joy was when he received a shiny five-franc coin from wealthy clients—two francs more than the daily allowance allotted for each of us by the Cojasor. The large tips only intensified his sense of having arrived at a city of endless possibilities.

Late at night, César and his friends would amble over to lively Montmartre, where the cafés were always open and welcoming. At a bar near the lobby of a local hotel, he noticed two elegant, intriguing-looking women in heavy makeup and expensive clothes, night after night having drinks together. It took a while before my brother and his friends realized that the chic women were men, and they understood they were a million miles from Cairo.

Near the Violet Hotel was another landmark, the Folies Bergère, the music hall that was as iconic a symbol of Paris as the Eiffel Tower or the Louvre, and whose gorgeous showgirls were renowned the world over for their sex appeal and glamour. César took to meeting his buddies by the Folies Bergère in the evenings. They’d stand on the corner in their blousons noirs, trying to look suave as they smoked Gauloises and eyed the dancers sauntering in and out. Occasionally they had a gig inside. The manager had spotted the youths loitering by the theater, and he hired them on some nights to prime the audience. While enjoying front-row seats, my brother and his friends were paid to clap loudly and cheer as the showgirls performed their numbers. It was delightful work, a far cry from the dismal routine of a refugee, and it also gave César a window into the mysteries of the legendary showgirls. Onstage, they sparkled and smiled and performed with exceptional grace and agility. But up close, my brother noticed with dismay, they were a lot older, more jaded—more ordinary—than he could ever have imagined. Stripped of their glittering costumes, the beauties of the Folies Bergère weren’t even that beautiful.

If he were more introspective, César could have viewed the experience as a metaphor—for Paris and women and life beyond Cairo. He could have pondered how beauty invariably disappoints, and how nothing in this world, not even the most dazzling city and its most delectable women, ever lives up to expectations.

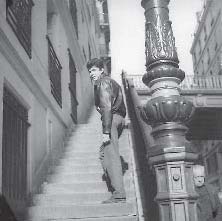

César in his blouson noir(black leather jacket), Paris, 1963.

But with his extreme literal-mindedness, my brother walked away from his work as a shill for the Folies Bergère only with a vague distaste for showgirls.

One night, as he stood with his friends eyeing the crowds gathering in front of the dance hall, he spotted a tall man in a dark luxuriant wool coat and top hat, walking out the door with a beautiful woman clinging to his arm. He recognized him at once. It was Maurice Chevalier, the movie star who was as much a symbol of Paris as the Folies Bergère. But unlike the showgirls, Maurice Chevalier didn’t disappoint a bit. He cut a striking figure, as dapper and distinguished as in his movies. My brother and his friends could only stare as he flashed his famous smile their way, doffed his hat, and kept on walking. César had again the sensation of living in a dream city, and whenever he’d think about our time as refugees and how we had survived and what he had loved the most about Paris, he would conjure up the night he saw Maurice Chevalier.

My mother didn’t care for any of this.

She was deeply disturbed that her eldest son was staying out all hours of the night and languishing on street corners like a hoodlum. She was the first to realize, even before my father, that she and Leon no longer exerted the same power over their children as before. In the world outside of Egypt, my siblings were either too alienated or too rebellious to heed what my parents had to say.

She turned to the social workers at the Cojasor for help, and they duly recorded her sense of desperation in Dossier #45,135. But Madame Dana and her colleagues confessed there was nothing much they could do. We were in a state of limbo. There were restrictions about working full-time, and it was impossible for César or Suzette to go to university because we could leave France any day. The social worker could only counsel patience.

Meanwhile, I discovered my favorite spot in all of Paris. It was a small doll factory a few steps up the passage, whose door was usually left ajar, so I could peek in every morning on my way to school and on my way back. The factory was heaven as defined by a seven-year-old girl—hundreds and hundreds of dolls, in various states of completion and undress, all lined up on shelves.

There were dolls without heads, and heads without dolls. There were dolls on racks with no clothes on, and dolls decked out in their full finery. There were dolls with long cascading hair and dolls that were bald. On a stand, miniature wigs were piled one on top of the other—blond curls, red tresses, dark sweeping chignons, sultry pageboys, all waiting for their turn to be placed on the head of some lucky doll and make her beautiful. In those restless final weeks in Paris, that became my favorite activity: marching obsessively past the factory’s open door and staring at the dolls.

A breakthrough came in late October: my father was summoned to the rue Lota and asked by HIAS to sign a promissory note.

We were going to America. The document stipulated that we would have to repay any money advanced to us to cover the expense of traveling by ship to New York, including taxes and inland transportation. There was also the freight cost of moving our 1,510 pounds of luggage—a staggering amount of pajamas, lingerie, bedding, pots and pans, sardine cans, and one twenty-year-old wedding gown.

The HIAS loan was routine for the agency, which after all was in the business of sending destitute refugees to America and other countries. The agency would typically purchase tickets and advance families the money to cover travel expenses, expecting them to repay the agency years down the road, when they were back on their feet again.

No amount was specified on the promissory note Dad was asked to sign. We were agreeing to a loan for an unknown sum. My father signed it anyway, of course, though it was only months later, in New York, that we learned the extent of our indebtedness: $1,199.94.

We were finally on our way when I suddenly developed another of my mysterious maladies. I became violently ill with a fever, a rash, a stomachache, and an excruciatingly sore throat. My mother fretted as she bundled me up in bed under every blanket she could cull from the Violet Hotel’s poorly stocked linen closet.

My father decided to summon the kindly Dr. Sananes, who had given him a glowing bill of health: he would pay for the house call using a week’s allowance, if need be, but at least I would be seen by a proper physician, without having to trek to one of the public clinics, where we had found the care to be singularly unimpressive. In my case, all that our local dispensaire did was order more and more blood tests. Typically, I wasn’t even seen by a doctor but by nurses. I longed for the distinguished men in white coats bending down to examine me in their private studies in Cairo. I even missed the Professor, of the white gloves and the cold and formidable manner.

Did the West really have a superior medical system to ours? Not in the Paris we had come to know.

When Dr. Sananes arrived, he glanced at our shambles of a hotel room, with suitcases piled one on top of the other, and shook his head. After examining me, looking at my throat, taking my temperature, and peering at the rash I had developed, he rendered his diagnosis.

I had la scarlatine—scarlet fever—a dangerous infection whose key symptom was the pink rash that seemed to be spreading. The disease often began as a simple sore throat, he explained, but could turn fatal. We shouldn’t even think of traveling to America now—not for months. He offered to sign a note asserting that under no circumstances could we leave France.

My parents were stunned. How on earth had Loulou contracted scarlet fever? they asked each other.

News of my illness reached HIAS, the Cojasor, and every other agency handling our case. The officials reacted with alarm. The diagnosis was so dire, it threatened to unhinge their meticulous travel plans. HIAS had finally managed to book the family tickets aboard the Queen Mary, which was to sail from Cherbourg to New York in early November. Clearly, because of my scarlet fever, we weren’t going to make the voyage.

Telegrams about my plight were dispatched to any number of overseas offices. “The youngest, a little auburn-haired girl, is sick,” read one cable. There was now an even bigger question mark. When would my family, which had already consumed an inordinate amount of resources, attention, and psychic energy from the local and international relief agencies, finally be able to leave France?

Between our inability to make decisions, our endless need for services, my siblings’ unhappiness, and the clear signs of discord in our family, we had taxed these relief and support agencies to their limit, and they were anxious for us to be on our way.

Agency officials debated how it was possible for a seven-year-old girl in a Paris hotel to contract la scarlatine. Was this an elaborate plot to remain in France? They had certainly heard of refugees delaying their departure to linger in Paris, but inventing a deathly illness for a young child would be a first.

At last, agency officials thought of sending over a seasoned doctor to examine me and confirm the diagnosis. My mom was overjoyed. “Le bon docteur arrive,” she cried, once again praying for the mythical, all-knowing physician of her imagination.

For once, she wasn’t disappointed. A distinguished French doctor holding a small black bag knocked on our door and made his way immediately to my bed. He seemed oblivious to the chaos in the room. After examining me thoroughly, he rendered his diagnosis: I only had a sore throat, maybe a severe sore throat, at most a strep.

What of the scarlet fever? my father asked.

“Absolument pas,” he declared. With his calm, commanding manner, he seemed to have stepped out of my mother’s dream of le bon docteur. He scribbled a prescription for an antibiotic on a pad and ordered me to stay in bed for another week. After that, he said, I was free to go to school—or even to America.

When my dad offered to pay him, the doctor said, “Non, merci,” shook hands, bowed, and left.

My father was so distraught at Dr. Sananes and his dire pronouncement that he called him. Why had he frightened us with his diagnosis of scarlet fever, he asked the young doctor, when all I had was a sore throat? The physician seemed puzzled. He had assumed we wanted to stay in Paris a while longer, that we needed more time to prepare for our journey. He had tried to do us a favor now by stressing the grave nature of my illness, knowing that a family with a sick child would be able to stretch out their stay in France.

Within a matter of days, HIAS announced they’d bought new tickets for us on the ship’s next crossing, in early December. The ocean liner was to sail from Cherbourg, with a weeklong voyage that would get us into America shortly before Christmas. They were purchasing five and a half tickets for the family.

I was the half.

There were no elaborate preparations for our voyage this time, no major shopping expeditions. In one brief burst of anxiety, my mother insisted that my father take me at once to a shoe store. I had to have a pair of boots, she said: it was the only way to shield “pauvre Loulou” from a country likely to be even colder than France.

Hand in hand, Leon and I walked to Montmartre and its bargain-basement stores. There, in the window of a popular discount chain, were dozens of children’s boots—boots with thick fur lining, suede boots, rubber boots, and boots entirely of leather. I had never owned a pair of boots, so the mere act of trying them on felt like an adventure.

I pounced on a pair of jaunty galoshes. My father agreed to buy them, though they were plastic and flimsy. But he also nudged me gently toward a practical pair of blue suede boots that reached past my ankles, with furry pile lining and thick yellow soles of caoutchouc—rubber. They looked like an Eskimo could happily have worn them. My father examined the lining with an expert eye and nodded his approval.

I felt tough and invincible as I stomped around the store in my arctic boots. I felt ready for America.

A couple of weeks before we were scheduled to leave, we heard a scream coming from the passage Violet.

“Ils ont assassiné votre président!” the porter was shouting toward our window—They have killed your president! My family looked at one another, thoroughly befuddled. Had Nasser been murdered in Egypt? Had they assassinated King Farouk in his Italian exile? Or was it General de Gaulle who had been killed here in Paris?

It took a few minutes before we realized that “our president” was the president of the United States. John F. Kennedy was dead. All day, my family huddled around the small table. The small leather-cased transistor radio we had purchased in Alexandria, and which had been our lifeline to the outside world since leaving Egypt, was blasting.

I caught only the same six words, “Le Président Kennedy a été assassiné,” repeated over and over again. My parents and siblings seemed shaken. They spoke in such low voices, I couldn’t make out what they were saying.

Discussions about where we should go resumed with intensity, and were more agitated than ever. Should we really move to New York? What kind of country were we going to that murdered its own leader? Even Farouk, the victim of a military coup, had been permitted to leave safely and sail out of Egypt aboard the Mahrousa, the royal yacht.

Our decision appeared terribly flawed, though we felt helpless to change course. Of all of us, my sister reacted the most emotionally. Only when Alexandra died had I seen her cry so copiously. To Suzette, the murder of JFK underscored the inchoate fears and misgivings she’d felt all along about the family moving to America, the sense that it was fundamentally the wrong place for us.

A couple of weeks later, we boarded the train to Cherbourg, where the Queen Mary was waiting to take us to America. We were all glum. César, who had liked Paris more than any of us, felt as if he were waking up from a dream.

When we arrived in Cherbourg, my father and I broke off from the rest of the family and took a long walk. It was after sunset, and we always loved to walk together at night, though I noticed that his gait was more tentative in the dark, and I wondered if he was in pain.

Dad and I found ourselves standing in front of a massive ocean liner shimmering in the still dark waters. It was the Queen Mary, so close we could almost touch it. Vast and imposing and stretching out for what seemed like a mile, it was like no ship we had ever seen before. In comparison, the Massaglia was a shabby little rowboat. Yet despite its majesty and heft, the Queen Mary offered us little comfort, and indeed, even heightened our sense of terror.

Or perhaps it was simply despair we felt at finding ourselves staring at another ship we would be boarding for yet another voyage into the unknown. I held my father’s hand a little more tightly as we lingered, dazzled and scared at the same time.

Dad was still in his faded raincoat, which had become his armor during our months in Paris. He was trying to come to terms with the fateful decision he had made. He realized, of course, that choosing America over Israel dashed any hope he had of rebuilding what he had lost. Never again would he live within walking distance of his brothers and sisters, never again would the family come together as in the dining room on Malaka Nazli, the men in their crisp new cotton pajamas, the women in their elegant robes, looking to him—the Captain, the patriarch—for guidance.

My father’s entire life had been guided by the primacy of family that was the Aleppo way. Family above work, family above money, family above ambition, family—though his wife would deny it—above personal pleasure. Yet there we were, on our way to a city where we had no one except a handful of relatives who didn’t care enough about us to meet us at the dock.