4

A VISIT TO THE FACTORY FLOOR

Babies haven’t any hair,

Old men’s heads are just as bare;

Between the cradle and the grave

Lies a haircut and a shave.

—Samuel Hoffenstein (1890–1947)

The thrum, thrum, thrum of the disinfectant machine upstairs blends with the sound of Hmong folk music playing on a small boombox radio plugged into the wall. Posters of old football players are taped to the gray painted interior of the William Marvy Company factory floor inside a spick-and-span brick warehouse. Of the fifteen employees, most work in the adjacent offices and retail shop. A handful of men make the barber poles and stir the vats of disinfectant. Most have been there for years.

Chue Vang holds a fine-tipped paintbrush in his right hand and dips it into an oozing glue-like mixture of floor filler and water. It’s the same caulk formula the William Marvy Company has been using for decades. He delicately dabs the paintbrush along the base of a barber pole skeleton, adhering the glass in place.

Outside on this February morning, it’s cold and sunny in St. Paul. The light filters into the old used car garage that has served as the Marvy plant and center of operations for more than fifty years.

Chue is forty-five and has worked for the Marvy family for thirteen years. He’s one of three Hmong workers among the fifteen William Marvy Company employees. When the company cranked out Barber Pole No. 75,000 in 1998—a pole now in the Smithsonian—Bob Marvy shut the plant down and took everyone to the nearby St. Clair Broiler restaurant and a Minnesota Twins game. The nice gesture came with unexpected hurdles. The company’s Hmong immigrants brought their own rice to eat instead of the burgers on buns at the Broiler. And the Twins game baffled them.

Chue Vang, forty-three, is a Hmong immigrant from Vietnam War–torn Laos. He has worked for the William Marvy Company for fifteen years making barber poles, among other tasks. Photo by Curt Brown.

Chue’s father fought for the CIA in his native Laos during the Vietnam War, and the family joined thousands from Hmong clans making their way to St. Paul. Chue is part of the largest urban concentration of Hmong immigrants in the United States who somehow selected the land of the windchill factor as their new home after the Vietnam War.

Although the Marvy 55s are the traditional mainstay of the company since 1950, the St. Paul, Minnesota firm makes poles in an array of sizes. These hang in the plant, waiting to fill orders in New Jersey in July 2014. Photo by John Doman.

Chue goes around and around with his paintbrush, circling the bases. These barber tadpoles, just clear glass cylinders and aluminum bases at this point, will sit and rest for a few days until the glue and caulk dries.

In a windowed office in the back, Scott Gohr bends over what he calls a mandrel. He’s got a title as rare as they come: barber pole technician. His mandrel looks like a massive wooden rolling pin you’d use in making bread. He takes red, white and blue–striped sheets of thick plastic-coated paper and rolls them through the mandrel until they become bonded cylinders. He crimps the ends like pie crust and fastens them with a metal clasp. They used to use striped parchment paper, placing it beneath the glass so that it was tucked inside the cylinder. But those old paper inserts tended to fade and age in the raw weather of Minnesota and exposed street corners across the world. So Scott works with something called acetate sheets—multicolored in red, white and blue—bonded with a solvent during its roll through the mandrel machine.

Scott is fifty-six and just celebrated his thirtieth year at the William Marvy Company. His hair is long and grayish white, pulled in a ponytail that drops down to his lower back. His beard is full and white. He nods at the irony. If everyone had hair as long as his, there would be no need for barbers or barbershops or barber poles.

“Bill was a little bit against the long hair, but he never said anything,” Scott said. “It was never like ‘stay away from me.’”

Scott Gohr, a longtime Marvy employee and barber pole collector, rolls a cylinder on a new pole in July 2014. Photo by John Doman.

New cylinders were lined up and ready to be inserted in the latest batch of Marvy barber poles in July 2014. Photo by John Doman.

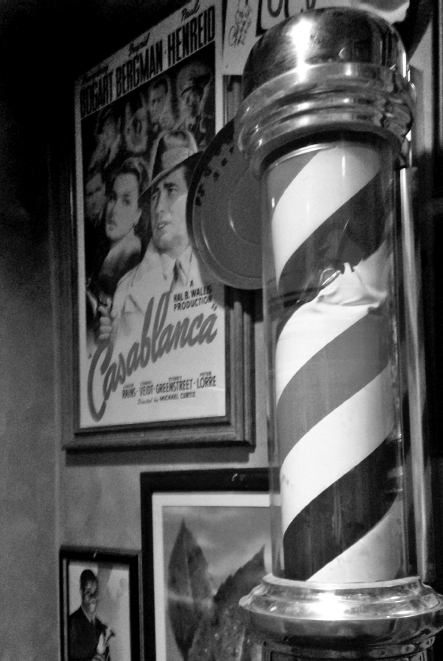

Many Marvy barber poles, like this Model 77, No. 77,375, no longer hang outside barbershops. This one hangs by the men’s room door at an Applebee’s in Durango, Colorado. Photo by Curt Brown.

It was just the opposite, in fact. Scott was laid off from his job at a battery-making plant in the early 1980s and began working construction. He was on the crew adding the second floor to the factory when Marvy hired him.

“He was a great storyteller and when I started in the shop, he sat me down and spent two hours telling me the ins and outs of the whole process, the business of selling things and production. He was a go-getter, always business conscious and just loved what he was doing.”

Before long, Scott became a fanatical barber pole collector himself, with a suburban garage crammed full of wooden pillars and pedestal poles, porcelain-bowled poles and even a neon sign from 1929. He’s got a floor model in his living room and another pole mounted in his bedroom. When collectors or antique hounds call for a part, he’ll not only track it down but also cross-reference their serial numbers with the red logbooks in the vault to tell the owners when their poles were made. He’s been known to trade parts—an engine for a porcelain base deal was recently struck—as repairing and renovating old barber poles for the antique market evolve into a larger share of the Marvy business. About one-third of the poles these days go to decorative uses in dens, lounges, restaurant and offices.

Scott often visits the ledger books, stored on the same shelf in the vault. When I was there, he opened the first one, which includes this detailed notation in William Marvy’s neat, cursive handwriting:

First pole delivered—assembled by Wm Marvy. Upright standard 55 hand-painted black. Model No. not shown on plate. Made 2-17-50. Sold by Geo. Kimble 2-21-50 to: Stanley Olson, Rt. 1, Grantsburg, Wis, Returned for service 5-24-50—loose on bottom due to improper fit. Returned to barbershop on 5-31-50. This was the original pole—rebuilt. I held it on our premises for several years—then sold it to George Dennmeyer, 205 E. 4th St., St. Paul, MN. for $90.00.

“That’s the neat part, I just love the nostalgia,” Scott Gohr said, wrapping another acetate swath of red, white and blue into a cylinder on his mandrel.

It’s a short walk through the small retail shop from the factory floor to the adjacent office portion of the William Marvy Company. William’s old oak roll-top desk sits in the front lobby—as if he just stepped away for a minute to schmooze a dealer over his favorite lunch: a chopped liver sandwich from a nearby deli.

Although William Marvy has been dead for more than twenty years, his image is everywhere at the offices that bear his name. Framed photographs hang in a conference room crammed with an unofficial museum full of old catalogues, letters, barbering tools and even an old barber chair. And there are, of course, dozens of barber poles sprinkled throughout the plant: from wooden pillars and crank-up keyed ones to the gold-plated No. 50,000, which hangs high on a wall in the back shipping area.

These logbooks, kept in the Marvy Company vault, include every serial number, model number and day of manufacture of the eighty-five thousand poles made since 1950. Photo by Curt Brown.

Bill’s son, Bob Marvy, has shared his six decades with all those barber poles. He was not quite two when his father and Bill Harris emerged from the basement with the first one in 1950. Family lore said his dad let him flip the switch.

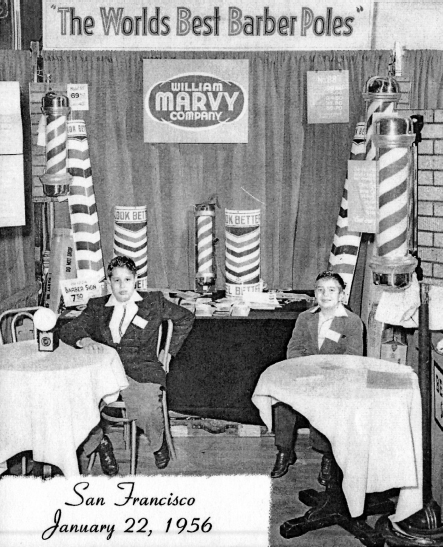

At the barber supply show in San Francisco in 1956, William Marvy’s sons, eleven-year-old Jim and eight-year-old Bob, manned the family business booth. Courtesy of the Marvy family.

Amid the boxes and scrapbooks in the conference room archives, there’s a photograph taken in 1956, when Bob was eight and his big brother, Jim, was eleven. They’re manning their old man’s booth at the barber supply trade show in San Francisco. The boys sit in their sports coats, surrounded by barber poles and a sign claiming that these are “The World’s Best Barber Poles.”

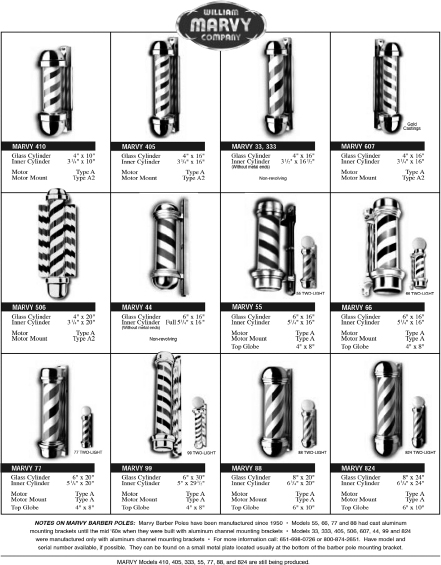

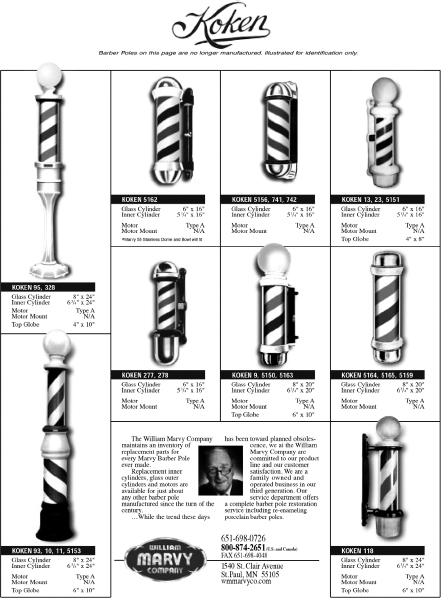

A big man like his father, Bob has kept the business afloat through all the lean years. In 2014, the company filled 598 orders for barber poles, which come in seven different models with various wall mounts and stands. They range from the eighteen-inch-tall Model 410 for about $500 to the signature Model 55, which remains twenty-eight inches with sixteen inches of glass. The two-light model, with a round white globe on top, goes for about $700, depending on which dealer, catalogue or website you use. You can get the granddaddy of them all, the forty-seven-inch, two-light Model 824 for roughly $1,000 through the popular Bowman Beauty and Supply Catalogue. There are also Models 77, 88 and 33.

“There is no rhyme or reason behind the model numbers,” Bob admits. “Just something Dad came up with. None of it made any sense.”

Barber Pole Identification guide. Courtesy of the Marvy family.

The prices range from $480 to $1,200 and depend on what kind of mount you get. Older ones can fetch higher prices through the antique world.

“They are a less expensive pole to manufacture than the cast-iron and porcelain poles,” Scott Gohr said between cylinder rolls on the mandrel. “Nowadays, that would be so expensive. These aren’t cheap either, but it’s a quality pole.”

Spoken like a true William Marvy disciple. Scott Gohr and Bob Marvy shrug off competition from China, where cheap plastic poles are being mass-produced and jeopardizing the near monopoly they’ve enjoyed for decades. They’ve lost track of other European and Japanese makers who have come and gone over the years. Makers of smaller, decorative poles—aimed for desktops and dens, not barbershop windows—have emerged in recent years. As have makers of barber pole lapel pins and other spinoffs.

The advent of computerized, light-emitting diode (LED) barber poles can’t be too far off. It will be curious to see how the Marvy Company, in its third generation, responds to the challenge. Not quick to make changes in a tried-and-true formula, Bob Marvy worries that the company’s long and storied use of dealers to peddle its barber poles might fall victim to the Internet.

“We’re old school, but our network of dealers is shrinking rapidly,” he said. “We used to have them in the warehouse, but now dealers don’t stock them. So everything is special ordered.”

Years after many businesses went cyber or perished, the Marvys are considering going with a website called barberpolesdirect.com to keep their product vibrant. The logbooks in the vault, containing data that have yet to be imported into a computer system, reflect the old-school nature of the Marvy business.

Making that long-awaited shift to more of an Internet-based business model will likely fall on the shoulders of William Marvy’s grandsons and Bob’s boys—Scott, Dan and Brad. According to the Family Business Institute, only about 30 percent of family businesses make it to the second generation, and only a paltry 12 percent survive into a third generation. A mere 3 percent of family businesses extend to a fourth generation.

The Marvy third generation, all boys who range in age from thirty-four to forty, have offices and responsibilities at the company. Scott is the chief financial officer and handles day-to-day operations. Dan supervises customer relations, and Brad is working his way up as a shipping clerk. They make the trek to trade shows from Las Vegas to New York just like their dad did with his dad.

“I remember when I got my first badge for the summer show when I was in high school,” said Dan, the middle son at thirty-eight. “My dad started introducing me to people in the business.”

His father never pushed him, though. Just the opposite: “He said, ‘If you want to do something else, you should.’”

The late William Marvy’s son Bob (front left) runs the third-generation family business with his sons, Dan (back left), Brad (back right) and Scott (front right). Photo by John Doman.

Bob Marvy, photographed in 1997, has carried on his father’s legacy along with his sons Scott (middle) and Dan. They are among only 12 percent of family businesses to make it to a third generation. But no kids have been born to a fourth generation, so the end of the line is coming for the last barber pole family. Courtesy of the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

So Dan worked for sixteen years at the St. Paul Jewish Community Center, manning the athletic pro shop and staffing the summer activities at Camp Butwin. Eventually, though, the lure of family proved to be too strong.

“It was always my grandfather’s wish to keep the business in the family,” Dan said. “I realized I might inherit part of this.”

He said he never felt the rebellious streak pushing him to get away from the family business, unlike many third-generation business inheritors. Instead, he takes deep pride in telling people he’s part of the last barber pole–selling family around.

“People say, ‘Oh, you mean those red, white and blue things that hang outside barbershops? You make those?’ It can be tough with the economy and getting the respect from the older generation. But my dad went through those issues, and in the end, it’s rewarding to try to keep it going.”

Chor Xiong, a worker at the William Marvy Company, put his finishing touches on pole No. 84,945 in early 2014 for an order from Toronto. Photo by Curt Brown.

As for the fourth generation, well, there is no fourth-generation Marvy yet. None of Bob’s sons have children. But customers seem to enjoy supporting a business that has endured three generations.

“They always mention how impressed they are by the longevity of our family business,” Bob Marvy said. “And my father would be absolutely thrilled to see how we’re carrying it on.”

Back on the floor a few days later, the glue and caulk were dry. Chue Vang and Chor Xiong used paintbrushes with shellac and silver paint to match the aluminum casings. Scott Gohr placed small rotary motors in the cylinders, and the crew wrapped them up in sheets of bubbled plastic for shipping. All told, the poles have about fifteen major parts—most fabricated away from the factory but assembled in the brick fortress on St. Clair Avenue in St. Paul.

Cylinders wait to be added to the newest poles in July 2014 with orders coming in from as far away as France and Kuwait. Photo by John Doman.

This serial number tag from a Marvy Model 55 in Rocky Hill, Connecticut, was a gift from a customer to Nazim Salihu, a Kosovar émigré who opened his own shop. It dates back to March 10, 1960, according to the logbooks at the William Marvy Company in St. Paul, Minnesota. Photo by Nazim Salihu.

By the end of the week, eighteen Model 405s—the twenty-four-inch, lean member of the line—had been boxed and were ready for shipping to France, where a dealer would distribute the swirling cylinders of glass and stainless steel to barbershops or Americana collectors across the French countryside. The serial numbers etched into the steel plates affixed to the standard’s spine were jotted down in the newest of the red ledger books in the vault.