“I am large, I contain multitudes.”

—Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself”

No TV. No computer games. No choice of free-time activities. And when noncompliant, no food, no water, no bathroom, and no shelter.

To many people, these rules sound like they came straight out of an American prison on a bad human rights day. In reality, they are a few of the parenting tips Amy Chua offers in her 2011 memoir, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother.1 An American-born daughter of Chinese immigrants, Chua reveals the parenting secrets of the Chinese, who are famous the world over for their successful children.

Underlying Chinese and Western2 differences in bringing up the kids, says Chua, is how parents think about their children’s selves—their I’s, egos, minds, psyches, or souls, to use the technical terms. Western parents assume that children’s budding selves are fragile, and so they empower their youngsters with choices and fortify them with praise. But Chinese parents “assume strength, not fragility,” writes Chua.3 As a result, they set the bar dizzyingly high for their children, and then use tough techniques to help them meet the family’s expectations.

If the proof of the parenting is in the offspring, Chua’s mothering is so far unassailable. Her elder daughter, Sophia Chua-Rubenfeld, made her Carnegie Hall debut at age fourteen, graduated first in her class from an elite prep school, and is now studying at Harvard University. Chua’s younger, “rebellious” daughter is no slouch, either. Louisa, an honor student at the same elite prep school, was a virtuoso violinist in the local symphony’s Prodigy Program, until she chose to dedicate more time to tennis, at which she also excels.

Despite the triumphs of her self-styled “Tiger Cubs,” Chua has outraged much of the Western world. Critics call her methods manipulative, abusive, and even illegal. They protest not only her means, but also her ends. “[Chua’s] kids can’t possibly be happy or truly creative,” writes columnist David Brooks, summarizing the public’s concerns. “They’ll grow up skilled and compliant but without the audacity to be great.”4 Consequently, they’ll crash into the so-called bamboo ceiling instead of rocketing to the top.5

This is not a new line of thought. For several decades, the West has dismissed the genius of the East as one of imitation not innovation. But the East is swiftly catching up with the creativity and audacity—the greatness—of the West. Between 2004 and 2008, Chinese scholars penned 10.2 percent of the scientific research papers published in major international journals, second only to scientists in the United States. Those rankings are expected to flip as early as 2013, with China taking the pole position.6 Applying what these scientists find, Asian companies are dominating the emerging industries of clean energy and alternative transportation.7

Science and technology are not the only areas of innovation with tigers at the top. Of the thirty-five living artists who earn seven digits for a single work, seventeen are of Asian heritage.8 Here in the United States, Asians make up only 5 percent of the population but fill three to nine times that number of undergraduate seats at the nation’s top universities.9

Stats like these fuel the sales of Chua’s book. What if she is right? What if raising successful children requires the rigid enforcement of old-school rules? What if the European-American preoccupation with self-esteem, self-expression, and self-actualization is turning our children into hothouse flowers who will wither in the grip of their Eastern competition? What if the clash of Eastern and Western cultures in American classrooms, and around the world, ends with the East on top?

At the heart of the Tiger Mother hysteria are two deeper questions: What kind of person will not just survive, but thrive in the twenty-first century? And can I be this kind of person?

Our book is an answer to these questions. As cultural psychologists, we study how different cultures help create different ways of being a person—what we call different selves. We also study how these selves in turn help create different cultures. We call this process of cultures and selves making each other up the culture cycle. As we will reveal, many of the clashes that give us the most grief arise when different selves collide. But by using our culture cycles to summon the right self at the right time, we may not only stop many of these clashes in their tracks, but also harness the power of our diverse strengths.

Most of us ponder the question “Who am I?” at some point in our lives. The more neurotic among us do so several times before breakfast. But have you ever asked yourself, “What is an I? And why do I have one?”

Your I, your self, is your sense of being a more or less enduring, single agent who acts and reacts to the world around you, and to the world within you. Your self is the hero at the center of your life story, which you are constantly writing (whether you know it or not).10 It is the part of you that perceives, attends, thinks, feels, learns, imagines, remembers, decides, and acts. It connects your present to your past and your future, helping you make meaning out of your experiences and figure out what to do next.

Having a self is a smart human trick. Because humans are not custom-built for any environment, you must be ready to adapt to all environments. And so your brain, like all human brains, is tuned to a broad band of stimuli.

Your world, in turn, is like a radio playing many different stations at once. Your self moves the dial on that radio. It helps you attend to the channels that are relevant to your needs and goals, and tune out the ones that aren’t. At a cocktail party, for example, you prick up your ears if someone says your name, even when you are not paying attention to the chatter around you. That’s because some part of your brain is looking out for information about your self.11 Similarly, you are much quicker to respond to ideas and events that are relevant to your self than to ones that are not.12 And if you want to remember a new fact, one of the surer routes to deep storage is to link that fact directly to something you value or have personally experienced.

Your self not only selects what information you attend to, but also puts it all together into a coherent experience. Your self makes playlists. It switches between the channels on the world’s radio, creating soundtracks with distinct feelings and stories. In so doing, your self also directs just which dance you are going to do, which course of behavior you will take. With your hip-hop playlist on, you will probably not do much two-step.

Although we all have an overriding sense of our self as the same across places, times, and situations, when we look more closely at the stories of our lives, we see that we actually have many different selves within our one self.13 And they all know how to work the radio. Depending on which self is “on,” you act very differently. For example, when visiting their mothers, many otherwise calm and reasonable adults are shocked to realize that their inner preteen self has taken over the dial. Likewise, when we gear up for an after-work basketball game, we are pleasantly surprised to find that the burned-out drone who was just whinging in his cubicle has finally relinquished the dial.

Yet there is order in the chaos of your many different selves. For all the varieties of self inside you, we find that most of them sort into two basic styles: independent and interdependent. Independent selves view themselves as individual, unique, influencing others and their environments, free from constraints, and equal (yet great!). As we will show, this is the sort of self that mainstream American culture overwhelmingly nurtures. Most of the songs on its radio are about independence.

Interdependent selves, by contrast, view themselves as relational, similar to others, adjusting to their situations, rooted in traditions and obligations, and ranked in pecking orders.14 As we will explain, the radios in many other parts of the world—including the East, from which Amy Chua’s family hails—feature mostly interdependent channels.

| TWO STYLES OF SELVES | |

| Independent |

Interdependent |

| Individual | Relational |

| Unique | Similar |

| Influencing | Adjusting |

| Free | Rooted |

| Equal (yet great!) | Ranked |

With Japanese psychologist Shinobu Kitayama, Hazel Rose Markus, this book’s coauthor, first examined independence and interdependence in the United States and Japan. Over the years, their graduate students (including Alana Conner, this book’s other coauthor) branched out to explore independence and interdependence in other nations, as well as in gender, racial, and class cultures. Findings from Kitayama and Markus’s Culture Lab form the backbone of this book. Across these many studies, we find that independent and interdependent selves are equally thoughtful, emotional, and active, but often have subtly different thoughts, feelings, and actions in response to the same situations.

Like many people with Eastern heritages, Amy Chua is using her interdependent self to raise interdependent children. (But she also uses her independent self to promote her book and to defend her ideas—a point we return to later.) She dedicates thousands of sleep-deprived hours to helping her daughters meet the high expectations of the important people in their lives. She in turn expects her daughters to give pride, comfort, and support to the people who helped them succeed. With so many relationships protecting Sophie and Louisa’s interdependent psyches, Chua assumes that her daughters are tough enough to take a little tussling. So she keeps up a steady stream of criticism to push her kids up to scratch.

In contrast, many of Chua’s Western critics front their independent selves. When given a child to rear, they help him cultivate his individuality and uniqueness so that he may distinguish his self from that of others. Many independent parents are also sleep-deprived, but not from holding their children’s feet to a fire they laid before they even had children. Instead, these parents spend a lot of time, money, and effort giving their children a wide range of choices—soccer or swimming? piano or painting? drama or debate?—so that their young can select activities that click with their allegedly inborn and unique talents. Because their children’s developing selves are delicate, Western parents keep up a steady stream of praise to protect and strengthen them.

Steeped in these different worlds, the children of independent and interdependent parents grow up to have different selves. Just ask them. When European-American students describe themselves, they tend to list their stable, internal, unique, and positive qualities, and rarely mention their roles or relationships. They say, “I am free-spirited and unique,” “I always try to be optimistic and upbeat,” or “I’m self-confident.”

In contrast, Japanese students tend to mention other people and relating to them within their first sentences. “I do what I want to do as much as possible, but I never do something that would bother other people,” says one participant. Another reports, “I behave in order for people to feel peaceful.”15

You can also sense the different selves of European-American and Japanese adults in their e-mails and text messages. For Americans, the most common emoticon is :) or the smiley face. The second most common emoticon is :(or the frown. Japanese writers also use smiling and frowning emoticons, but they just as frequently use (^_^;), which depicts cold sweat rolling down a nervous face. Japanese use this emoticon when they are worried that they have done something wrong and disturbed a relationship. When interdependence is the goal, a symbol that says, “I am worried about how you are feeling,” is more useful than one that just expresses what the writer is experiencing.16

Now think about your self. Do you tend to use your independent or interdependent side? Or do you use both sides equally?

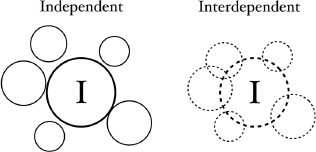

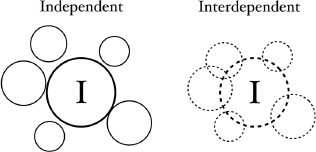

Take a look at the two images that follow to help you answer. The independent self on the left is surrounded by people. But they all have solid edges, and they do not overlap. This kind of I is individual, unique, and free. And though other people clearly matter to this sort of self, they are not a core feature of the I in the middle.

In contrast, the interdependent self on the right has a porous edge, as do all the people surrounding it. They are also all intersecting; this is a self whose relationships with others are essential ingredients. In addition, an interdependent self is made up of not only its relationships with individuals, but also its place in the web of everyone else’s relationships. This is a relational, rooted, and ranked self.

In chapter 10, we will give you more tools to discover how you combine independence and interdependence to make your distinct self. We will also show throughout this book that the forms independence and interdependence take vary across cultures and people. But at the heart of independence is a focus on one’s own self, while the heart of interdependence is a focus on one’s relationships.

Chua’s memoir captured the collision of Eastern interdependence and Western independence. It also stoked a clash all its own between its interdependent advocates and independent critics.

Yet the clash between independent and interdependent selves is not just an East-West issue. In the following chapters, we show how it ignites a surprising number of other local, national, and global tensions, including:

These culture clashes are becoming more frequent, stressful, and even violent. With new technologies bringing our outsize populations together, we more often interact with people whose ways of being don’t jibe with our own, and who therefore leave us baffled. As resources disappear, we must compete even more fiercely with these mysterious people for degrees, jobs, and a decent standard of living. At the same time, we increasingly help people whose intentions and actions we don’t fully understand, from neighbors and coworkers of different races, classes, and genders; to people around the world suffering from war and poverty. Meanwhile, climate change, nuclear proliferation, and other global threats demand that we all cooperate more than ever before.

As our planet gets smaller, flatter, and hotter, what sort of self will rise above the fray and flourish?

Chua and the Eastern cultures from which her parents hail would perhaps suggest that interdependence is the way to go. With tight coalitions of people indebted to each other, interdependent selves may better withstand the threats and shocks ahead. After all, there is strength in numbers.

But Western psychologists have overwhelmingly held up independence as the happier and healthier way to be. From Dr. Freud to Dr. Spock to Dr. Phil, psychologists have urged people to realize their authentic selves, actualize their unique strengths, exert control over their environments, free themselves from burdensome obligations, and view themselves as equal to others (who also happen to be great, hence the high levels of self-esteem in these parts). They point out that independent selves don’t just sit back and weather the storm; they change the weather altogether. These same psychologists also sternly warn against excessive interdependence, with its bugbears of codependency, inconsistency, and passivity.

As twenty-first-century cultural psychologists, however, we are writing a new prescription. To build a more prosperous and peaceful world, everyone must be both independent and interdependent. This means that people who tend to be more independent will have to hone their interdependence, while people who tend to be more interdependent will need to polish their independence. Success in love, work, and play will come to those who wisely apply the best self to the situation.

Although many people have a strong tendency toward either independence or interdependence, we all use both kinds of selves. A White male CEO, for example, is a very independent creature until he crawls on the floor with his three-year-old, where he gets in touch with his more interdependent side. Likewise, an otherwise interdependent working-class Latina nurse’s aide conjures plenty of independence when she starts a movement to reduce pollution in her neighborhood.

By knowing when and how to use our different selves, we can not only better understand the clashes around us, but also avoid many of them altogether. Both independence and interdependence are legitimate and useful ways to be a person. Yet clashes arise when we channel an independent self for a situation that calls for interdependence, and vice versa.

For instance, let’s say you’re in the market for a new car. So is your good friend. In the end, you buy exactly the same car as your friend, a few days after he makes his purchase. Have you just offended your friend or cemented your relationship?

As it turns out, the answer depends on your friend’s social class. Psychologist Nicole Stephens and her team asked working-class firefighters and middle-class MBA students to imagine just this scenario. They found that the MBA students, with their strongly independent selves, were aghast. “It spoils my point of differentiation,” one complained. “Why did he do that?” asked another. “I wanted to be unique.”

Yet the more interdependent firefighters weren’t the least bit bothered. “I think it’s cool,” one said. Another offered, “I’d be like, yeah, awesome, let’s start a car club.” A friend’s choosing the same car was hardly an affront to the firefighters’ interdependent selves; instead, it was an act of solidarity.17

This doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t spring for that Camaro just because your buddy has. It does mean, however, that if your buddy is a college-educated, middle-class European American with an independent self, copying his ride is likely to trouble your relationship.

By tuning in to other people’s selves, you may not only avoid clashes, but also get more of what you want. As we discuss in chapter 3, for example, a woman who wants to earn more must access her independent self to ask for a raise. Likewise, as we demonstrate in chapter 9, an aid worker who wants to prevent famine in a Sudanese village must work within the interdependent traditions, norms, and hierarchies already at play there.

The Tiger Mother herself may agree with our prescription. In the less famous final chapters of her book, Chua admits that she has been too harsh with her second-born and embraces a more independent style. “I did the most Western thing imaginable: I gave her the choice,” she writes. “I told her that she could quit the violin if she wanted and do what she liked instead, which at the time was to play tennis.”18

Chua is not alone in her struggles to apply the right self. We all wrestle with the question of which psyche to bring to a given situation. What makes our two-self solution even harder is that you often aren’t controlling which of your selves shows up. As Malcolm Gladwell popularized in his bestseller Blink, psychologists have long known that most of what actually drives your behavior sails under the radar of your conscious awareness. The same holds true for which self you use: subtle cues in the environment can evoke independence or interdependence without your even knowing it. These cues, called primes, don’t determine how you’ll act, but they do raise the odds that certain thoughts, feelings, and behaviors will rise to the surface.

And so changing your I is not simply a matter of making up your mind, all by your lonesome. You must also change the cues in your environment. These cues are part and parcel of what we call culture. By culture, we don’t mean the opera, the symphony, or the ballet. Nor do we mean merely the foods, festivals, and clothing that distinguish, say, Mexicans from Indonesians. Instead, culture is the ideas, institutions, and interactions that tell a group of people how to think, feel, and act.

Although some primates have the rudiments of culture, no one has culture like Homo sapiens. And no one has culture like you. We all have many different cultures crisscrossing through our lives, from major cultures like nations, genders, and social classes; to subcultures like professions, hobbies, and even sports-team fandom. But few people (maybe no one) swims in the exact same cultural mix as you. Your special cocktail of cultures combines with your biology to make you you.

No one makes culture like you, either. Every day of your life, you make culture without even consciously trying to. That’s because your everyday thoughts, feelings, and actions feed into the cultures of which you are a part, just as your cultures shape your thoughts, feelings, and actions.

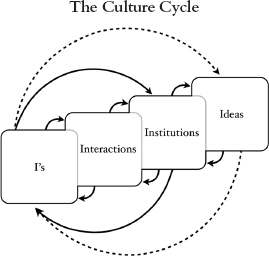

To help explain how the culture cycle rolls, we’ve broken it down into four elements: I’s, interactions, institutions, and ideas. These elements work together like this:

Your I (self, mind, psyche, soul) anchors the left side of the culture cycle with its thoughts, feelings, and actions. The right-hand “culture” side of the cycle includes interactions, institutions, and ideas. You can think about the culture cycle starting from either the left or right side. From the left: your I (or self) creates a culture to which you later adapt. From the right: your culture shapes your I so that you think, feel, and act in ways that perpetuate this culture.

The part of the culture cycle we experience most often is our daily interactions with other people and with human-made products (artifacts). These interactions follow seldom-spoken norms about the right ways to behave at home, school, work, worship, play, etc. Guiding these practices are mundane cultural products—stories, songs, advertisements, tools, architecture, etc.—that make some ways to think, feel, and act easier than others.

The next layer of culture is made up of the institutions within which everyday interactions take place. Institutions spell out the rules for a society and include legal, government, economic, scientific, philosophical, and religious bodies. No single person knows all the laws, policies, origin stories, or theories at play in their cultures. Nevertheless, institutions exert a formidable force, silently allowing certain practices and products while forbidding others.

The last and most abstract layer of the culture cycle is made up of the central, usually invisible ideas that inform our institutions, interactions, and, ultimately, our I’s. Like the unseen forces that hold our planet together, these background ideas hold our cultures together. Because of them, cultures have an overarching pattern. To be sure, cultures harbor plenty of exceptions to their own rules. But they also contain general patterns than can be detected, studied, and even changed.

Because you actively construct your cultures, you are not a slave to them. When people are mindful of the cultural forces around them, they can amend, riff on, or even altogether reject their influences. This is why we have technology, revolutions, and progress, rather than just “same species, different century.”

Being aware of the culture cycle is the first step to controlling it. Once you know that the environment is full of primes that shape your behavior, you can begin to consciously override these cues, or even replace them with more desirable ones. To give a small example: Anyone who has successfully dieted knows that it takes more than an iron will and clenched jaw to shed the pounds. You also have to make changes in the everyday environments with which you interact. You must liberate your pantry of its chips and your freezer of its ice creams and replace them with fruits and vegetables. You must park your car farther away from your destination so that you get more exercise. You must surround yourself with the friends and family who support you, and figure out something else to do with your drinking buddies.

Yet the idea that an individual can single-handedly alter the course of the culture cycle is a perpetual Hollywood fantasy. Though you are not a slave to your cultures, you are not the lone master of them, either. Because your self and your cultures are so inextricably intertwined, changing your self and your world requires changing your culture cycles. In particular, you must alter the cycle’s interactions and institutions, in addition to your I. You cannot directly alter the big ideas that animate the entire culture cycle, because they are so deeply rooted. But over time, as I’s, interactions, and institutions shift, big ideas follow suit. And once a new big idea takes hold, a sustainable new culture cycle begins to churn.

To return to the weight-loss example: To keep the pounds off, you should work with the institutions in your community to make maintaining a healthy lifestyle easier. You should ask workplaces to make stairwells safer and easier to take than the elevator. You should encourage markets to offer you more fresh produce and less processed food. You should lobby city governments to set aside plenty of safe, open space for you to exercise. And you should support laws and taxes that protect you from unhealthy foods and food additives.

A more substantial example of what it takes to change culture cycles is the civil rights movement. Tweaking any one part of the culture cycle puts small dents in the problem of racial injustice. Using education to change individual hearts and minds (an individual-level intervention), improving portrayals of minorities in media (a change at the interactions level), and abolishing Jim and Juan Crow19 laws (an institutional alteration) can move the needle toward greater racial and ethnic equality on their own. But widespread and sustainable change requires ongoing efforts at all three of these levels simultaneously. Over time, these actions in the lower levels of the culture cycle will displace the big idea that some racial and ethnic groups are inherently better than others.

Most of the culture clashes in your daily life will be easier to fix than five hundred plus years of racial injustice. Nevertheless, the same rule holds true: there are no silver bullets. Changing the self or changing the world requires altering the culture cycle that makes them both. Yet as we will demonstrate, a few well-placed nudges can set your culture cycles off in a better direction.

Just because people can change their selves and cultures does not mean that they do so readily. A major obstacle is that many people don’t even realize that they have cultures. They think that they are standard-issue humans, that they are normal, natural, and neutral. It’s all those other annoying people who let cultures bias their ability to perceive the world as it actually is.20

This line of thinking is especially widespread in middle-class European-American culture, where the independent I is thought to be a self-made self. Consequently, middle-class European Americans often ignore social forces when explaining why people do the things they do, and instead focus on people’s internal traits, talents, and preferences. Cultural psychologists call these inside-looking explanations for behavior dispositional attributions. In contrast, people in interdependent cultures more often look outside individuals and make more situational attributions for their behavior.

Psychologists Michael Morris and Kaiping Peng tracked these two dramatically different styles in English- and Chinese-language newspapers’ reporting on two mass murderers: Gang Lu, a Chinese graduate student in physics at the University of Iowa who killed his adviser, several bystanders, and himself after he lost an award competition; and Thomas McIlvane, an Irish-American postal worker who shot his supervisor, several bystanders, and himself after he lost his job in Royal Oak, Michigan. The New York Times and the World Journal (a Chinese-language newspaper published in New York) covered both tragedies, but told very different stories. American reporters spilled more ink describing Lu as a “darkly disturbed man” with a “bad temper” and a “sinister edge,” and attributing McIlvane’s crime to his “short fuse,” mental instability, and other personal qualities.

In contrast, Chinese reporters dedicated more column inches to situational factors. For Lu, it was the bad relationship with his adviser, the lack of religion in Chinese culture, and the availability of guns in American society that drove him to kill. For McIlvane, tensions with his supervisor, the example of other mass slayings, and the fact that he had recently been fired had led him to homicide.21

Because independent selves believe that people’s internal qualities drive their actions, they also believe that they react to what’s inside people, not to their cultures. As a result, many Americans claim to be color-blind, gender-blind, class-blind, religion-blind, or otherwise culture-blind. We can be forgiven for some of our willed blindness, as some of it reflects the best impulses of the civil rights movement, the feminist movement, the elder rights movement, and other attempts to make the world a fairer place. If people discriminate because of culture, many activists reason, then ignoring culture will help end discrimination. Just treat all people as individuals, the thinking goes, and soon, peace will guide the planet and love will steer the stars.

The main problem with this solution is that it’s impossible to implement. The culture cycles of nation, gender, race, class, region, and religion have especially deep roots in the world. Even nine-month-olds distinguish between people of different races and genders.22 This does not mean that people are born racist or sexist, or are otherwise hell-bent on making each other miserable. Instead, it means that having and making cultures is so important to our species that we begin learning cultural categories as soon as we pop into the world.

Making cultures is our other smart human trick. (The first, as you recall, is having a self.) Because of culture, we don’t have to wait for genetic mutations or natural selection to give us the biology we need to live in a different terrain, to extract nutrients from new foods, or to cope with a change in climate. Instead, we can invent new shelters, cooking techniques, and climate-appropriate apparel. We can also save ourselves the trouble of reinventing these technologies by learning from our fellow humans how to make them.

Pulling off these nifty innovations requires exquisite social coordination. As British artist Thomas Thwaites recently demonstrated, no human alive today could build a toaster from raw materials all by himself. All the mining, milling, fabricating, assembling, and shipping behind this humble appliance involves thousands of people with highly specialized skills.

For feats ranging from building toasters to launching spaceships, culture helps us sort out who does what, when, where, and how. When a human is born, she is hungry for this cultural information. Her brain has evolved to receive cultural inputs, and so her nature is to seek nurture. Her family, friends, and the many strangers who help keep her culture cycles turning are ready to oblige. With their help, she quickly sees that people of different sexes have different hair, clothes, toys, and friends. With a little experience, she finds that people of different races live in different neighborhoods, hold different jobs, and commit different crimes. She learns that people of different religions have different holidays, places of worship, and values.

These particular cultural divides are not inevitable. We can (and sometimes do) carve up the world differently. We could create Legions of Tall People and Societies of the Short. We could establish separate republics for brown-eyed, blue-eyed, and green-eyed people. (David Bowie would enjoy dual citizenship.)

Yet getting rid of culture altogether is not possible. Millions of years of evolution have wired the need for culture in our brains, and thousands of years of civilization have installed the furniture of culture in our worlds. And so calls for culture-blindness are naïve.

Instead of sweeping culture under the rug, we should embrace it, understand it, and, most important, mobilize it for good. As modern life becomes more complex, and social and environmental problems become more widespread, we must relearn to use our culture cycles and our selves the way nature intended. And that means capitalizing on our diverse strengths. Returning to the radio metaphor: our selves must tune in to more of the world’s stations. The more varied playlists that would result would give us more tools with which to meet the challenges of our shrinking planet. At the very least, they would make for more interesting listening.

Chua was on to something. But culture clashes don’t have to cause so much suffering. By deftly combining our smart human tricks, we can fit many more selves and their culture cycles into one world.