Chapter 6

Ethics and politics

We have now considered how the phenomenon of prophecy was fitted into epistemological theories in the Islamic world. But some prophets do not just know things that the rest of us don’t, they also bring a revealed law. This is foundational for both Judaism and Islam, and has posed a further set of questions for philosophers. They sought to reconcile the religious norms laid down in the religious law with the ethical and political norms established by unaided human reason. In articulating those rational norms, thinkers of the Islamic world drew on ideas from the classical tradition. Arabic works on ethics were inspired by two sources in particular: as usual Aristotle, and also Galen, who was himself influenced by Plato and the Stoics. In politics, the most prominent idea to come from the Greeks was Plato’s ideal of the philosopher-king. Could such ideas be shown to agree with the teachings of the Qurʾān or the Jewish law? Or did the religious sources effectively render the Hellenic inheritance superfluous?

The state of the soul

Although Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics is the most famous ancient ethical treatise, and was translated into Arabic in the formative period, the early tradition of Hellenizing ethics in the Islamic world was not dominated by Aristotle. A good deal of ‘popular’ moralistic material came into Arabic from Greek and other languages. This was probably the most widespread sort of secular ethical literature in Arabic (see further Box 18). It included collections of sayings (‘wisdom literature’) ascribed to famous figures, including ancient philosophers; ‘mirrors for princes’, like the famous Kalıla wa-Dimna, a book of animal-based fables translated from Sanskrit by way of Persian; and books of practical advice, for instance a work on household management by the otherwise obscure Roman-era philosopher Bryson.

As early as al-Kindı, we see how these sub-genres were being received and interwoven. One of his works is a collection of remarks supposedly made by Socrates, who was confused in the Arabic tradition with Diogenes the Cynic (for instance al-Kindı has Socrates living in a wine jar). Another is a work of advice aimed at an aristocratic audience, if not actual royalty, which explains how to avoid becoming sad. Towards this end, al-Kindı invoked philosophical doctrine, advising us not to value physical things, since unlike intelligible objects they are subject to change and destruction. Yet he also quoted from wisdom literature, including a story about Alexander the Great, repeating sayings of Socrates, and elaborating on a classical allegory found in Epictetus, which compares our earthly life to a temporary disembarkation from a ship: like the passengers, we should be ready to leave at a moment’s notice.

Box 18 Adab and philosophy

In the formative period, there were highly specialized philosophers like al-FārābI and the members of the Baghdad school. But philosophical material had a far wider dispersion in upper-class society through the refined activity known collectively as adab. Sometimes translated as ‘belles-lettres’, adab showed off an author’s linguistic skill, wit, and good taste. Such authors occasionally criticized the falāsifa and their beloved Greek sources. In one much-quoted passage, the greatest exponent of adab, al-Jāḥiẓ (d. 868–9), expressed his scepticism about the prospects of translating Greek successfully into Arabic. He also mocked al-KindI in a book of comic anecdotes about misers. Yet al-Jāḥiẓ has aptly been called a ‘bibliomaniac’, and his wide reading made him familiar with Greek ideas and deeply knowledgeable about early kalām. Later adab authors, such as al-TawḥIdI (d. 1023), depict a literary salon culture in which it was the done thing to sprinkle quotations from Greek philosophers into one’s dinner conversation. But we should not rule out a more serious engagement with philosophy on the part of these literary stylists. Al-TawḥIdI was a multi-dimensional figure, a scribe and court intellectual who exchanged views with Miskawayh, wrote an overview of the intellectual sciences, and was attracted to Platonist philosophy and sufism.

By concentrating on ways to forestall sadness, al-Kindı implied that the purpose of writing about ethics is to help the reader to attain peace of mind. This had been the goal of many Hellenistic ethicists, too. Routes to ataraxia (‘freedom from disturbance’) ranged from the restrained hedonism of the Epicureans to the belief-free detachment attained by ancient Sceptics. Neither of these two schools was particularly influential in Arabic, however. More decisive was the impact of the Stoic-flavoured Platonism found in the ethical works of Galen. As the leading authority in medicine, his works were voluminously translated into Arabic, and in the bargain two of his writings on ethics passed into the Islamic world. These ethical treatises too offered a sort of medical care—therapy for the soul, rather than the body. It was a commonplace of Hellenistic ethics to compare peace of mind to physical health, and ethical advice to medicine. For instance Epicurus’ ethics were distilled into four recommendations called the ‘four-part cure (tetrapharmakos)’. The titles of two early Arabic ethical works show that this medical analogy was alive and well in the formative period: Spiritual Medicine and Benefits for Bodies and Souls.

The first is by Abī Bakr al-Rāzı, notorious for his five eternal principles. His Spiritual Medicine found much more favour with subsequent readers than that cosmological theory. It was written as a companion piece to an encyclopedic work on (bodily) medicine. It is an entertaining but ethically demanding treatise, which takes as its starting point Plato’s distinction between three parts in the soul, which al-Rāzı knew through Galen. The Spiritual Medicine exhorts the reader to subdue the lower two souls, the desiring and irascible faculties, to the higher part, which is the rational soul. It is reason that makes us human, and letting oneself be dominated by the lower, body-dependent souls is in effect living as a beast (see further Box 19). A sign of this is the way that animals go after everything they desire as soon as it is presented to them, whereas humans have the ability to refrain from this. Often the Spiritual Medicine presents such self-control in hedonistic terms, as an Epicurean might have done. Self-control brings more pleasure and less pain in the long run, for instance by preventing discomfort due to overeating.

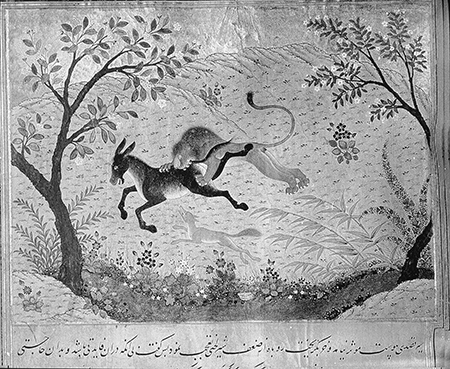

Box 19 Animal welfare

Given that many of these ethical texts encourage us to suppress our lower ‘animal’ souls, we might expect them to offer little in the way of sympathy towards real animals. And it is true that animals were often ignored in philosophical literature (unlike in the visual arts: see Figure 8). Yet there were exceptions. A belief in God’s mercy is a fundamental tenet of Islam, and theologians sometimes extended this to animals. Some Muʿtazilites postulated that animals might receive food in paradise to recompense them for whatever suffering they had to undergo on earth. Several medieval ethicists, meanwhile, argued for benevolence towards animals. One example is Abī Bakr al-RāzI’s Philosophical Life, which contains an impassioned criticism of those who overburden pack animals or enjoy hunting, on the basis that we should show mercy to animals as God shows mercy towards us. Al-RāzI did allow cruelty towards animals in order to save human life, for instance riding a horse to death to escape an enemy, and said that one may kill predatory creatures, since this is a net gain in terms of animal welfare. Another remarkable text for this topic was produced by a group of philosophers writing in the 10th century, who adopted the name ‘Brethren of Purity (Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ)’. Their collection of epistles includes a fable which imagines the animal kingdom bringing an official complaint to the king of the jinn, protesting at the treatment they receive from humans. The portrayal of animals here is extremely positive: they are ‘monotheists’ and ‘muslims’ who pray to God with their calls, and unlike humans they are free from sin. Nonetheless, the trial is eventually decided in favour of the humans, since it is they alone who can include truly pious, saintly figures among their number. For another example we may turn to Ibn Ṭufayl’s island story Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān. At one stage in the narrative, the title character decides to participate in God’s providential activity by protecting and nurturing not only animals, but also plants. Ḥayy even becomes a fruitarian, restricting his diet to food he can harvest without killing plants. As in al-RāzI, the attention paid here to animal welfare is not justified with reference to the intrinsic dignity of animals or anything of the sort. Rather, kindness to animals is a way of carrying out God’s will.

But unlike the Epicureans, al-Rāzı was no hedonist. He was simply trying to show that even people focused on desire-satisfaction have good reason to subordinate their desires to rational control. Elsewhere, al-Rāzı made it clear that pleasure has no value at all, since it is nothing but the restoration of the body to a healthy state after it has been in a harmful state, as when we drink to restore our balance of moisture. This is a zero-sum game, since the pleasure attendant on the process is always matched by the deficiency or pain being eliminated. On the other hand, enjoying pleasure is not intrinsically evil, either. Pleasures enjoyed in a controlled and thoughtful way were allowed by al-Rāzı, as we can see from another short work called The Philosophical Life. Here he defended himself from the accusation that he failed to live up to the standards set by Socrates, who was famous in the Arabic tradition for being an ascetic (in part because of the confusion of Socrates with Diogenes). Al-Rāzı’s response was that Socrates was only an ascetic as a young man. Later he outgrew this and adopted a more mature, moderate lifestyle which included such things as wine-drinking and marriage.

Benefits for Bodies and Souls is by a contemporary of al-Rāzı, who was also an associate of al-Kindı: Abī Zayd al-Balkhı (d. 934). As the title indicates it has two main sections, dealing with physical medicine and ethics. Like al-Kindı and al-Rāzı but within an even more explicit ‘medical’ frame, al-Balkhı treated his subject as a therapeutic one. All three authors gave advice on avoiding sadness; both al-Rāzı and al-Balkhı discussed a range of other psychological ‘maladies’ such as excessive anger and envy. As al-Balkhı put it, the advice offered for these conditions is intended to ‘keep the soul’s faculties in a good and balanced condition’, much as a doctor would prescribe drugs or a change in diet to preserve or recover the balance of humours in a patient’s body. Al-Balkhı’s favourite therapeutic technique was the rehearsal of useful thoughts, which should be constantly called to mind to prevent or remove psychological distress. We should for instance remember that physical things are liable to destruction, and so value them less, anticipating their inevitable disappearance. Al-Rāzı’s Spiritual Medicine applies this same line of thought even to the loss of loved ones.

If such advice seems unhelpful, the problem may be that one cannot simply argue other people, or oneself, out of having desires. On its own, my rational understanding that my loved ones are mortal has no tendency to make me face the prospect of their deaths with equanimity. In the context of the Platonist tripartite soul, the problem here is that the lower souls are not responsive to the sort of considerations that move the rational soul to form its beliefs. Galen already saw this, and observed that we do many things because of the habits we have formed, rather than on the basis of belief. This means the lower soul must be habituated into following the lead of reason, like an animal being tamed. That process results in what he calls ‘character traits’, a term which in its Arabic version (akhlāq) became more or less synonymous with the subject matter of ‘ethics’.

Here we find agreement between Galen and the other main Hellenic source on ethics, Aristotle. His Nicomachean Ethics likewise argues that virtues are formed by habit, which is why moral education needs to happen already at a young age. One author who noticed the harmony between Galen and Aristotle was Miskawayh. His Refinement of Character Traits (Tahdhıb al-akhlāq) was the most elaborate and influential ethical treatise of the formative period. It makes extensive use of Aristotle, including his account of virtues as ‘means between extremes’ (for instance courage is the mean between the vices of cowardice and rashness). It also refers explicitly to the ethical works of Galen. This is typical of Miskawayh, who has no hesitation in combining Aristotelian ethics with doctrine with Plato’s tripartite soul alongside advice on child-rearing from Bryson. Also typical is the harmony he sees between all these Greek authors and the teachings of Islam. Not only does the Refinement occasionally quote the Qurʾān to show its agreement with Miskawayh’s ethical teachings. It also gives the religious law (sharıʿa) a specific role within that ethical teaching, by making it responsible for the very habituation we have been discussing: the law ‘sets the youth on the straight path, habituates them to admirable actions, and prepares their souls to receive wisdom, to seek the virtues, and to reach human happiness’.

This idea was developed within the context of Judaism by Maimonides. Like Miskawayh, Maimonides was heir to both the ‘medicalizing’ Galenic ethics and Aristotle’s theories. He duly presented vices as diseases caused by reason’s failure to dominate the lower soul, and saw the virtues as means between extremes. We get from the former to the latter through rigorous habituation, which is precisely what is offered by the religious law. An obvious example might be that following dietary laws teaches Jews to exert control over their desire for food. Maimonides saw a potential problem here, though. If we turn to the Bible, we often find that the patriarchs are depicted as rather ascetic. Abraham, for example, refrained from looking at his wife’s body and from collecting spoils that were justly his after military victory. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, such heroic abnegation has often been taken as a sign of piety and virtue. It may not be required, but it is certainly admirable. On Aristotle’s reckoning, though, these acts appear vicious, because they fall short of the appropriate mean with respect to the enjoyment of sex and wealth. Maimonides solved the problem by distinguishing between those who are already secure in their virtuous habits, and those who are still working their way towards perfect virtue. The latter group might rightly impose particularly severe constraints on themselves, all the better to condition themselves not to give in to temptation in the future. This is a policy that was often adopted by the patriarchs, on Maimonides’ reckoning, and we should not confuse it with perfectly virtuous comportment.

With his extensive reflection on Hellenic ethical theory, Maimonides makes a vivid contrast with earlier Jewish ethical literature, an outstanding example of which is the Duties of the Heart by Baḥya ibn Paqīda (d. c.1156). This is another book of advice, devoted to the goal of forming intentions that are pleasing to God rather than eliminating imbalances in the soul. Ibn Paqīda claimed to be innovating here. Many previous authors had dealt with external actions, including the ritual observances laid down in the Jewish law. He wanted to teach his readers how to cultivate an inner motivation of obedience to God. Ibn Paqīda sought to shift the focus of Jewish ethics from actions to intentions. A good intention on its own (which might not come to fruition, if it is thwarted by circumstance) has more value than the good action that is intended. Coincidentally, a similar focus on the ‘interior’ state of the ethical agent was being promoted at about the same time by Latin Christian medieval thinkers like Peter Abelard.

8. An image from a manuscript of the book of animal fables, Kalıla wa-Dimna.

The soul and the state

In the post-formative period, one of the most widely read philosophical works in any discipline was the Ethics (again, Akhlāq) for Nāṣir written by Naṣır al-Dın al-Ṭīsı. Despite the title, the book is not only about ethics. Al-Ṭīsı wanted to cover all branches of ‘practical philosophy’ as recognized by Aristotle. That meant dealing with ethics, but also household management (the original meaning of ‘economics’, a word that comes from the Greek for ‘household’) and political philosophy. Though the work is not without originality, it makes extensive use of existing materials, turning to Miskawayh for ethics, Bryson and Avicenna concerning the household, and al-Fārābı for political philosophy. In this al-Ṭīsı is in line with modern-day historians, who have recognized al-Fārābı as the most interesting political thinker of the formative period.

His Principles of the Opinions of the Inhabitants of the Virtuous City discusses God, cosmology and other issues in natural philosophy, and even prophecy, before turning to an account of the best city. The ideal city is contrasted to cities that pursue defective ends, like wealth or pleasure, and its success is achieved through the presence of a philosopher-ruler, who steers the city’s inhabitants towards virtue. In yet another example of the widespread ‘medicalization’ of ethics, al-Fārābı drew an analogy between the ruler’s relationship to the inhabitants’ souls and a doctor’s relationship to his patients’ bodies. Much of this sounds familiar from Greek sources, especially Plato’s Republic. Yet al-Fārābı’s political thought was highly original. Among its innovations was the notion that the ideal ruler is also a prophet, able to convey his knowledge in a form made palatable through the use of imaginative symbols. So the rest of the citizens, despite living in a city run according to philosophical principles, do not need to be philosophers themselves. This is, presumably, why the title of al-Fārābı’s work ascribes ‘opinions’ to the inhabitants, as opposed to full-blown knowledge. Applying his universal knowledge to the particular case before him, the ruler can govern the city in light of the needs of its population and local conditions, for instance climate or other geographical factors. He can also respond to new situations with renewed teachings. So long as he lives and is obeyed, the community will enjoy the fruits of his ideal leadership and be led towards virtue.

But what to do when the prophet dies? Unless the community is lucky enough to find another person of similar qualities, they will have to resort to other forms of guidance. A group of people might be found who collectively possess the abilities and characteristics of the perfect ruler. Failing that, the community must fall back on careful exegesis and interpretation of the law brought originally by the prophet. This is the task of jurisprudence (fiqh). Without access to the prophet himself, juridical scholars must comb through his teachings and apply them to novel questions or issues. So long as continuity is somehow preserved, the prophet’s knowledge is perpetuated as ‘religion (dın)’. Religion is analogous to philosophy, just as revelatory discourse is analogous to demonstrative proof. Like philosophy, it has both a practical and a non-practical part, with the adherents of a virtuous religion adopting the right beliefs concerning actions, and true opinions about God and the world.

Al-Fārābı scrupulously avoided explicitly connecting any of this to Islam. For instance we never find him identifying Muḥammad as an example of a prophet-ruler. The account was intended to be general, applicable to any virtuous religion. A similar approach was taken by one of the later thinkers most influenced by him, the Andalusian philosopher Ibn Bājja. In his Regime of the Solitary, Ibn Bājja again describes an ideal city and contrasts it to defective cities. The title alludes to the plight of right-thinking persons who find themselves in non-virtuous cities. Such people can attain happiness of a sort, but not the full happiness available to those living in perfect cities. Ibn Bājja calls them ‘weeds’, because they undermine the city in which they live. They have managed to develop correct ideas, either practical or theoretical, and thus represent a challenge to the convictions that hold sway in their vicious societies. In the Republic, Plato had Socrates wonder whether the ideal city he was describing could ever exist in practice, and propose that it could occur if by chance a philosophically minded son would be born to a king. The ‘weeds’ are Ibn Bājja’s answer to the same question. (For a less abstract view of dynastic change, see Box 20.)

For Ibn Bājja the ‘solitary’ philosopher is inevitably a kind of dissident, a living rebuke to the corrupt society around him whose very presence will tend to destabilize that society. Like al-Fārābı, he used the analogy of the doctor, but reserved it for the solitary philosopher in the bad city, since in the perfect city no one has a sick soul. Ibn Bājja’s fellow Andalusian Ibn Ṭufayl was more pessimistic about the ability of the philosopher to effect political change. At least, this seems to be the message of the final section of his Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān. After having become an accomplished philosopher and even enjoyed mystical union with God, Ḥayy encounters a visitor named Absal. He travels with him to another island, where the local inhabitants are adherents of a religion that sounds very much like Islam. Though Absal is able to recognize Ḥayy’s wisdom, the other inhabitants reject him. Ḥayy realizes sorrowfully that the people are not capable of benefiting from his teachings. They must instead cling to the detailed religious injunctions that regulate their lives, lest they fall into vice.

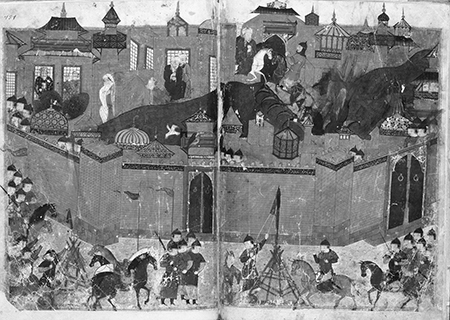

9. The sacking of Baghdad during the Mongol invasions.

Suhrawardı put his own distinctive spin on the Platonic idea of a philosopher-king, saying that the rightful caliph is someone who has mastered not only the discursive sort of philosophy practised by the ‘Peripatetics’ but also the intuitive methods used in Illuminationism. An Iranian thinker of the early Safavid period, al-Nayrızı, was unimpressed by these remarks. He speculated that Suhrawardı was trying to lay claim to political power for himself. This accusation is not as outlandish as it may seem, for Suhrawardı was put to death on the orders of Saladin because of the influence he exerted on Saladin’s teenaged son. On a less ad hominem note, al-Nayrızı pointed out that there has historically been no correlation between philosophical wisdom and political authority.

Box 20 Ibn Khaldīn on dynastic rise and fall

The 14th century was a time of great upheaval in the Islamic world. Plague swept through the lands, as did the warlord TImīr (often known as Tamerlane), who pushed Mongol hegemony even further than it had reached in the previous century. Meanwhile in the Western Islamic world, or Maghreb, the Almohads had lost Spain to the Christians and various powers jockeyed for control of North Africa. Witness to it all was Ibn Khaldīn, whose enormous historical work Kitāb al-ʿIbar (The Book of Observations) begins with a book-length introduction (Muqaddima). This sets out Ibn Khaldīn’s theory of dynastic cycles, a bold attempt to provide a template for explaining historical events inside and outside the Islamic world. According to his theory, civilizations are routinely toppled by tribal groups who draw on the powerful force of ʿaṣabiyya, or ‘group solidarity’. Typically, the tribal group will be rootless and nomadic, but will settle down in cities and towns once they have deposed a previous regime. The new sedentary life will soften them within a few generations, paving the way for defeat at the hands of a new challenger. The theory fits the history of Muslim Spain very well: the Iberian peninsula had seen a series of conquests launched from North Africa in previous centuries, with power passing from the remnant of the Umayyad caliphate to feudal kings, then to the Almoravids and finally to the Almohads. This is most likely no coincidence, since Ibn Khaldīn hailed from the Maghreb, having been born in Tunisia. But Ibn Khaldīn applied his account to other cases too, not least the extraordinarily rapid conquests of early Islam.

For al-Nayrızı and other Safavid-era philosophers, proper authority instead has its source in divine dispensation. The Prophet, and then the imams recognized in shiite Islam, were sent to provide not only revelation but also leadership for the community. It was thus a thwarting of God’s plan when the rightful imam ʿAlı was passed over as caliph. This shiite conception of political legitimacy could readily be combined with al-Fārābı’s ideas. After all, he too saw a close connection between prophecy and perfect leadership, and acknowledged the possibility of successors who would be able to carry on this aspect of the prophet’s role. So when another shiite philosopher, al-Ṭīsı, made use of al-Fārābı in the political section of his Ethics for Nāṣir, he could seamlessly weave shiite allusions into this material. (It has been argued that his Ethics bears the hallmarks of specifically Ismāʿılı shiism, which he espoused at this stage of his career.)

In sunni Islam, there has been more room for debate as to whether political power must ideally be allied to religious authority. Many sunni rulers have asserted this sort of double legitimacy. In the 9th century, when the ʿAbbāsid caliphs demanded assent to the Muʿtazilite position on the Qurʾān’s createdness, they were also demanding the right to define the boundaries of acceptable doctrine. We can find a parallel in Christian Europe at about the same time, with Charlemagne stepping into theological controversies over the nature of Christ and the worship of images. The rulers of sunni Islam have rarely gone as far as mandating theological positions in this way. In fact the ʿAbbāsid example discouraged later caliphs from doing so, since the inquisition over the Qurʾān’s createdness ultimately became politically unsustainable. It has rather been the religious scholars, or ʿulamāʾ, whose expertise in the core Islamic texts and the law has made them the usual arbiters of correct doctrine. When al-Ghazālı accused Avicenna of ‘apostasy’ and said that he would have merited death for holding his philosophical views, he was speaking as a legal scholar.

Still, religious and political legitimacy have often gone hand in hand. The Ottomans, for example, began as religious warriors (ghāzıs), and the sultans were always keen to present themselves as defenders of sunni Islam, against both the powers of Christian Europe and the shiite regime of Safavid Iran. That posture gained in credibility when they successfully took Constantinople, and extended their territory to include the religious sites at Mecca. Ottoman sultans also cultivated close ties to the ʿulamāʾ, who formed a powerful legal bureaucracy at the heart of Ottoman society. As these scholars came to form a distinct social class, allied to the sultan and passing on lucrative posts through a system that was more nepotistic than meritocratic, they attracted hostile critique. Reform was urged by the populist Kādızādeli movement, named after its founder Meḥmed Kādızāde (d. 1635). Philosophers too were alarmed at the corruption of the Ottoman ʿulamāʾ, as we can see in the case of Kātib Çelebi. Though he agreed to this extent with the Kādızādelis, he was concerned not to throw the baby out with the bathwater. The system of religious schools, or madrasas, that educated the ʿulamāʾ also provided an institutional context for philosophical and scientific knowledge in the Ottoman empire.

A couple of centuries later, though, some rationalist philosophers would be describing the traditional madrasa curriculum as backward, and as a hindrance to social progress. Such criticisms were made in both Ottoman and Indian society, as part of a call to arms in the face of colonialism. Some argued that adopting European political and scientific ideas might reverse the loss of territory and sovereignty. In the Ottoman sphere, two waves of reformers urged this policy: the Young Ottomans and then the Young Turks. The Young Ottomans were broadly careful to recognize the value and standing of both the sultan and the ʿulamāʾ, but they argued for political reform, for instance by changing from Ottoman absolutism to something more like a European-style constitutional monarchy. The more radical Young Turks, inspired by European thinkers like Durkheim, Büchner, and Comte, were less afraid to step on traditionalist toes. On the scientific and philosophical front, they embraced materialism and positivism; on the political front, they promoted nationalism, paving the way for the secularist project that would ultimately reach its fruition with the new nation of Turkey in the early 20th century.

These developments opened a new front in the struggle to determine the source of political authority in sunni Islam. On the reckoning of the nationalists and other modernizers, legitimate political leadership could be thoroughly secular. This was not presented as an abandonment of the teachings of Islam, of course. To the contrary, modernizers were eager to point to religious texts and aspects of early Islam that could bolster their political views. Thus the Egyptian scholar Muḥammad ʿAbdīh and his teacher Jamāl al-Dın al-Afghānı cited the traditional practice of shīrā, or consultation among the community, as an Islamic analogue to democratic government. Like Averroes, ʿAbdīh was a jurist who emphasized the social importance of religion. But he was dismissive of the traditional ʿulamāʾ, whom he saw as trapped in taqlıd, the unthinking acceptance of authority. Along with ʿAbdīh’s emphasis on individual reflection and political action went a rejection of fatalism, the view that all things are preordained by God. An article in the journal produced by ʿAbdīh along with his teacher al-Afghānı angrily rebutted the European conception of Islam as a fatalist religion. ʿAbdīh worried that fatalism could lead to quietism, since it implies that the current state of political affairs has, along with everything else, been decreed by God. Fatalists are bound to assume that if things are meant to change, then God will ensure that they do: an attitude inimical to the political engagement urged by the modernizers (see also Box 21).

Box 21 The political context of the kalām debate over human action

It was nothing new when early 20th century modernizers complained about the political consequences of theological fatalism. Debates over human action and free will had always been politicized. One of the defining features of Muʿtazilism was its stance on the Muslim who commits a grave sin: such a sinner is neither a ‘believer’ nor a ‘hypocrite’ but in an ‘intermediate position’. This apparently rather obscure teaching was offered as a compromise solution for a highly politicized issue. Some Muslims, notably the Khārijites, believed that those who had sinned through their political actions had effectively exiled themselves from the Muslim community, justifying military action against them. This led to violent schism, which the more tolerant Muʿtazilite formula was designed to avoid. The same goes for the notorious Ashʿarite teaching on human freedom, according to which God ‘creates’ human actions but the human agent ‘acquires’ them. The question here was whether God determines all events in the created world or whether humans have some scope for undetermined action. As ʿAbdīh would argue much later, a determinist position could easily be taken to legitimize existing political rule, since that rule has been determined by God. (Already the Umayyad dynasty cultivated an explicit link between their rule and God’s decree, or qaḍāʾ.) On the other hand, determinism could be taken to undermine personal responsibility: God decides whether each of us will sin, and we cannot change His decision. Wanting to steer well clear of this consequence, the Muʿtazilites insisted that it would be unjust for God to punish sinners if they were unfree. But this assumes that we humans are in a position to say what God can do within the bounds of justice. That seemed presumptuous to the Ashʿarites, who believed that God’s choices define what is just, rather than adhering to some external standard of right and wrong. Instead, they suggested a compromise of their own: humans are not in a position to ‘create’ their actions or anything else, but they still retain responsibility for what they do through their ‘acquisition (kasb)’ of the actions God assigns to them.

At about the same time, similar views were being put forward by Muslim rationalists in India. Indian thinkers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, like Sayyid Aḥmad Khān and Muḥammad Iqbāl, agreed with contemporary Ottoman modernizers that the Islamic world should not just welcome European science, but claim priority of discovery. Iqbāl argued that the medieval optical theorist Ibn al-Haytham (d. 1039) should take credit for pioneering experimental method, and that Miskawayh had anticipated Darwinian evolutionary theory. (Similarly, ʿAbdīh believed he could find evolution adumbrated in the Qurʾān.) More generally, Iqbāl saw Islam as a distinctively empirical religion. He referred to the Qurʾān’s repeated calls to observe nature and see it as the proof of God’s might and wisdom—texts cited centuries earlier in Averroes’ Decisive Treatise to prove the harmony of Islam and Aristotelian philosophy. Iqbāl was here influenced by the ideas of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, whom he had studied in Europe. Iqbāl followed Nietzsche’s idea that one should value this world rather than despising it, and agreed with him that world-denying tendencies were rife in Judeo-Christianity. Islam is different, though. It ‘says “yes” to the world’ and with its ‘reverence for the actual’ has encouraged Muslims to become ‘the founders of modern science’.

Nor did Iqbāl see any conflict between science and mysticism. Arguing against another Western thinker, William James, Iqbāl rejected the idea that mystical consciousness is wholly different in kind from empirical knowledge. The mystic simply grasps all at once what the scientist is grasping one part at a time. This commitment to the ultimate unity of knowledge is something Iqbāl shared with the earlier Indian sufi thinker Shāh Wālı Allāh. But Iqbāl’s Nietzschean distaste for world-denying philosophies meant dismissing the practice of ascetic withdrawal from the world as ‘false sufism’. Islam rather calls us to engage with the world, through both empirical science and political action. For Iqbāl the political ideals of Islam (which he equated with tawḥıd: ‘oneness’ or ‘monotheism’) are equality, solidarity, and freedom. Such ideals would be realized not by separating religion from politics, but by bringing all Muslims into a unified global community, crossing all boundaries of ethnicity and nation. Iqbāl was therefore critical of the sort of nationalist project urged by the Young Turks and by some of his contemporaries in India.

One political issue that increasingly came to the fore at this time was the rights of women. The reforms unleashed in the 19th-century Ottoman empire opened up new opportunities for women, including the chance to publish in journals and magazines. This is not to say that Muslim women had previously been entirely excluded from intellectual activities. Religious learning had often been passed from one generation to the next by women scholars, who played a major role in the transmission of the ḥadıth (reports about the Prophet). This began already with the Prophet’s favourite wife, ʿĀʾisha, one of the most prolific original witnesses of ḥadıth. Other women followed her example, observing the mandate that women should emulate the Prophet’s wives. In sufism, too, women played a significant role. Indeed one of the earliest significant mystics was female: Rābiʿa, who pioneered the idea that the sufi’s relationship to God is one of love and erotic longing, a central theme in the poetry of Rīmı.

More recently, the position of women in Islam has been interrogated by thinkers like the sociologist and feminist Fatema Mernissi. She has done empirical research, with extensive interviews of women in Morocco, and also built a case for gender equality by returning to the core texts of Islam. In her work Beyond the Veil, first published in 1973, she argued that Islamic society has long been gripped by a fear of women’s power over men. Such practices as polygamy, veiling, and the repudiation of wives are a collective ‘strategy for containing [women’s] power’. Mernissi contrasted this to the way that women have been seen as passive and weak in the European tradition, not least by Sigmund Freud (in making this point, she compared the Freudian understanding of women to remarks by al-Ghazālı). On Mernissi’s reading the traditional treatment of women represents a distortion of the original teaching of Islam. Using the techniques of ḥadıth scholarship, she argued that certain Prophetic reports used to justify this treatment (for instance ‘those who entrust their affairs to a woman will never know prosperity’) are unsound. They have been treated as trustworthy only because the misogynistic leanings of influential Muslim men led them to suppress the egalitarian aspects of the Islamic revelation.

Mernissi and other liberal Muslim thinkers have frequently presented their reformist agenda as a return to the original teachings of Islam. Another example is Sayyid Aḥmad Khān’s assessment of polygamy. Admittedly, Islam does allow a man to marry as many as four wives. Yet it also requires that the wives be treated with total equality. Khān argued that, since this is in practice impossible, polygamy is effectively prohibited in Islam after all. Ironically, a similar strategy of returning to the origins of Islam has also been adopted by far more socially conservative Muslims. For them a major inspiration has been Ibn Taymiyya, whose ‘salafist’ approach to jurisprudence took its name from the salaf, or first generations of Muslims. It would seem that for some centuries, Ibn Taymiyya’s influence was rather limited, but more recently he has probably played a more prominent role in political discourse in the Islamic world than any of the other historical figures discussed in this book.

Yet quite a few figures from previous centuries have continued to live on in contemporary political and philosophical discussion. Mullā Ṣadrā’s philosophy has had a particularly vibrant legacy in Iran. He influenced no less a political actor than the Ayatollah Khomeini, spiritual leader of the Iranian revolution, though the relationship between this revolution and the Ṣadrean philosophy of a 20th-century Iranian thinker like Ṭabāṭabāʾı is a matter of dispute. Even relatively minor figures have had a surprisingly powerful presence in recent intellectual developments. An example would be Miskawayh. We saw just now that Iqbāl gave him credit for advancing a precursor of the theory of evolution; his work was also taught at al-Azhar University in Cairo by ʿAbdīh; and he has been a source of inspiration for the Algerian thinker Mohammed Arkoun (d. 2010).

All of this is another reason to abandon the usual understanding of philosophy in the Islamic world as a branch of medieval philosophy. Certainly there were fascinating Muslim thinkers—and fascinating Christian and Jewish thinkers living among Muslims—in the medieval period. But the story of philosophy’s development in the lands of Islam after medieval times is one of continuity, not rupture or oblivion. ‘Medieval’ thinkers have never stopped being relevant, even if only indirectly, thanks to many generations of epitomizers, commentators, super-commentators, and critics. For all the innovation, all the pointed critique of predecessors, philosophy in the Islamic world has always remembered its own history.