Challenging Stolypin, Engaging Stolypin

SOON AFTER the Second Duma met, on the very night before Stolypin was to address it for the first time as prime minister, the roof of the chamber collapsed. It was before dawn, so no one was hurt. The collapse itself was, of course, a bad omen, but some of the reactions were worse. Pavel Krushevan, the deputy from Kishinev and one of the so-called Black Hundreds (the label loosely applied to vitriolic reactionaries and anti-Semites), on seeing the devastated room reportedly said “Good,” and “his face lit up with satisfaction.”1 On the left, a Kadet veteran of the First Duma insinuated deliberate government neglect, saying that inadequacies in the ceiling had been noticed in the First Duma and money appropriated for their correction.2

In the election campaign preceding the Duma’s convocation, the government had harassed the opposition with a blend of repression and incompetence. At a campaign event where Maklakov spoke of what “we,” the Kadet party, favored, a policeman interrupted to say that he mustn’t do so, because the party was banned (as it technically was). Maklakov switched to “they,” and that was apparently all right.3 Another government tactic also depended on the party’s unlawful status. Because of the indirect method of elections, voters chose only electors, who were typically people unknown or at least much less well known than the real candidates. Without lists linking them, voters were likely to get the electors’ names wrong, so official lists were provided. But the government invented a new rule, which had not applied in elections to the First Duma, disallowing official lists for the illegal parties. The Kadets got around this with their own unofficial lists, which evidently functioned satisfactorily. These government shenanigans, plus cruder measures such as arresting and exiling candidates under the extraordinary security laws, largely backfired, producing sympathy for the candidates opposed by the government and bringing the Kadets closer to the hard left parties.4

As a candidate Maklakov sought allies to left and right. On two occasions he stressed the unity of the left (that is, the Kadets and those to the left of them). In one of these he invoked defeat of the Octobrists as a goal and argued that “in great struggles that define the path of history, only two armies fight.” Despite this Manichean tone, in both instances his key pitch was that all on the left should get behind the Kadets, as the strongest party.5 So he seems to have been invoking leftist unity mainly as a device for promoting his own party—the least leftist of the leftists.

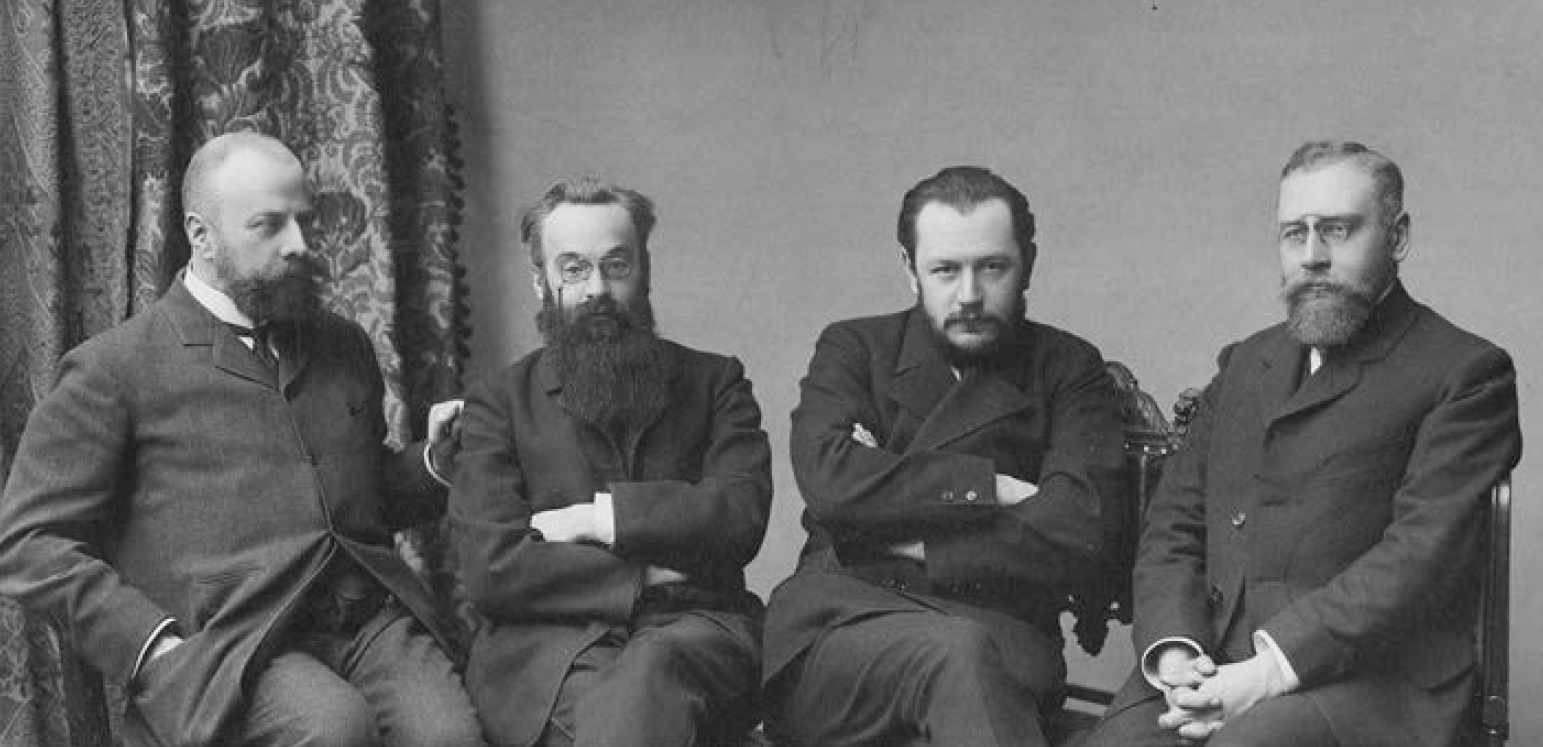

Three Kadet leaders (left to right): Prince Paul Dolgorukov, Alexander Kizevetter, Vasily Maklakov, and N.V. Talenko. © State Historical Museum, Moscow.

Maklakov made similar efforts to cultivate potential allies to his right. In the summer of 1906 he and some other Kadets met with representatives of the Octobrists, and an Octobrist splinter, the Party of Peaceful Renewal, to see if they could coordinate in the electoral campaign. The effort failed. Dmitri Shipov, one of the founders of the Octobrist party and then of its splinter, reacted to the government’s field courts martial decree—of which more shortly—by saying that the Party of Peaceful Renewal could under no circumstances work with the Octobrists, who were acquiescing in or even supportive of the decree.6 Maklakov’s outreach activities seem to have been driven by one primary goal—enhancing the Kadet position wherever allies could be found.

The electoral results confounded the government’s intentions in dismissing the First Duma. The most obvious effect was a hollowing out of the center. The Kadets and their adherents shrank from 185 to 99, or to about 19 percent of the membership. Slightly making up the loss to the middle was an increase for the Octobrists from 13 to 44. The Social Democrats, Socialist Revolutionaries, and Popular Socialists collectively rose from 17 to 118 (23 percent), while the Trudoviks edged up from 94 to 104 (20 percent). Those to the right of the Octobrists rose from zero in the First Duma to 64 in the Second (of whom only 10 seem to qualify as extreme rightist). Despite the shift to extremes, a centrist coalition on particular issues was conceivable. Excluding 2 percent classified as “extreme rightists,” and running leftward so far as to encompass the Trudoviks, one could nonetheless imagine—perhaps with a good deal of optimism—a centrist majority of 58 percent of Duma members. If we add in 9 percent for the Polish Circle, who often showed a moderate bent,7 this imagined coalition could prevail even in the face of losing most Trudoviks. Of course to assume that the Kadets themselves were centrist is, as we’ll see, a stretch.

The new Duma represented not merely a shift to the left. J. W. Riddle, the U.S. ambassador, cabled to Washington: “The present Duma has the reputation of being a less educated but more practical body than the one of last year. The leaders of the first Duma were doctrinaire professors of great learning and many theories, but with no experience of public administration or of business. In the present Duma this type is not at all prominent.”8 Maklakov agreed.

When Nicholas II dissolved the First Duma, he also appointed Stolypin, already minister of internal affairs, to be premier as well. As minister of internal affairs Stolypin had stood out in the Duma as articulate, self-confident, and relatively candid—going so far, for example, as to acknowledge the illegality of a police action, a concession that stunned the deputies by its novelty.9 Stolypin used the time between the dissolution of the First Duma and the convening of the Second to issue a set of decrees under Article 87, implementing a mixed program of reform and repression. Two reforms stand out. First, a decree of October 5, 1906, eliminated many of the disabilities of peasants vis-à-vis the other estates. This was broadly welcome, and Maklakov was later, in the Fourth Duma, to take a lead role in trying to extend it. A second decree, issued November 9, 1906, adopted the government’s preferred solution to Russia’s agricultural woes: it enabled individual peasants to obtain rights in land that would be more like ordinary property than what they then held: they received the opportunity (either as individual families or as a village), to opt out of the process of endless redistribution aimed at matching landholding with family size. In large part because Stolypin presented it as a substitute for the left’s solutions to Russia’s agrarian problems (confiscation of gentry land, with some compensation, and redistribution to peasants), it was anathema to the left (including the Kadets); conflict between the competing visions for agriculture fueled political warfare throughout the Second Duma.

On the repression side of the ledger was the government’s August 19, 1906, establishment of the field courts martial. The decree creating them came on the heels of an attempt to assassinate Stolypin at his residence on Aptekarskii Island, but the initiative and insistence on the decree came from the tsar, with Stolypin himself and Minister of Justice Shcheglovitov expressing skepticism.10 The law enabled military officers with no legal training to act as prosecutor, judge, and jury, taking the accused from charge to execution in three days, with no possibility of appeal. As Maklakov pointed out, the law directed an official to send an accused to such a “court” when the crime was so obvious that there was no further need for investigation, terms that seemed to call for an automatic guilty verdict.

Just as the government manifested a real program in the run-up to the Duma opening, a stark contrast to the launch of the First Duma, so the mood on the left was more moderate. Miliukov himself sounded a less militant tone—“not assault, but an orderly siege.”11 The Kadet slogan was “Save the Duma,” that is, avoid provocations of the sort that had precipitated dismissal of the First Duma. Maklakov endorsed this approach, arguing that at particular times it made sense to save the Duma, at others to strike the government with heavy blows.12

Another difference was a change in the Duma’s rules, introduced by a committee under Maklakov’s chairmanship. Maklakov and others believed that one reason for the futility of the First Duma was the waste of time in debate on bills that had not been through committee. To obtain the necessary clarity and specificity, Maklakov drafted, and the Duma in due course adopted, a Nakaz (rules or standing orders) that sharply limited debate over such inchoate measures.

The Second Duma’s legislative life began with Stolypin’s March 6 speech—the one that had been postponed because of the ceiling’s collapse. The speech is remarkable for the scope and depth of reforms it proposed. As Stolypin’s biographer Abraham Ascher writes, “If a liberal had delivered the . . . speech, a large number of deputies would have applauded most of it.”13 Of course Stolypin’s agrarian reform proposal was offensive to the left, but that occupied little of the speech. Besides that, Stolypin proposed laws enshrining the civil liberties referred to in the October Manifesto; reform of local government on a plane of equal relations between all estates; reform of the local court system to bring the local courts under control of the rural electorate; a general policy of getting the government out of the way of labor-management relations; organization of medical aid for workers; religious toleration; subjection of officials to both criminal and civil liability for excesses; and, perhaps most startlingly, abolition of officials’ power to impose administrative exile except in time of war or popular rebellion.14 Imagine how Russia might have developed if the liberal Second Duma had put aside its conflict with Stolypin over agrarian policy and set out to enact such a program.

In fact, the Duma’s leftist majority had resolved in advance to sit in stony silence regardless of what Stolypin might say. But one deputy, a Social Democrat, was bursting with such fervor that he assumed the tribune and delivered a scorching attack. The attack is familiar to history entirely because of Stolypin’s response. His few words included these: “What the revolutionaries say boils down to two words directed to the authorities, ‘Hands up!’ And to these two words, the government with complete calm and confidence in its right can answer with two words, ‘Not afraid’ [‘ne zapugaete,’ literally, ‘You don’t scare us’].”15 In his history of the Second Duma, Maklakov wrote, “For many of us only party discipline prevented us from applauding. The impression on the country was tremendous. . . . March 6 was the apogee of Stolypin’s popularity.”16 Maklakov went on to place the whole speech in context: “What was new and valuable was that he spoke as a true ‘constitutional minister,’ as the representative of a ‘constitutional ideology,’ understanding the rule of law and the need for an opposition to the authorities’ policies.”17

As we saw earlier, the government’s efforts to quiet the revolution encompassed both reform and repression, the latter most clearly taking the form of the decree on field courts martial. The crude summary justice that the decree unleashed, almost invariably ending in a hanging, led to the epithet “Stolypin’s neckties,” a tag that ironically originated with a rather moderate Kadet, Fyodor Rodichev. That the government needed to take some action against terrorist violence seems clear: In the one-year period starting in October 1905 the killing and wounding of government officials ran at a rate of about 300 a month. Thereafter the rate slowed a bit, but when private individual victims are taken into account, the total over the years 1905 through 1907 reaches more than 9,000.18 That, of course, is not enough to justify the lawlessness of the field courts martial.

When the Second Duma opened on February 20, 1907, the government knew that as a practical matter the measure could survive for two more months at the most. Recall that Article 87 gave the government only two options for a law enacted under that article. It could introduce a bill with the same provisions in the Duma; but in that case, the law would die whenever the Duma or the State Council voted it down; given the Second Duma’s composition, it was sure to exercise this authority and kill the decree. Alternatively, the government could offer no such bill, in which case the decree would expire automatically two months after the Duma resumed its sessions. Knowing the decree’s fate if it were introduced as a bill, the government offered none. The clock started running.

The Kadets nonetheless offered a bill affirmatively repealing the decree. The bill had no realistic prospect of having any effect, as that would require approval of the State Council and tsar, which, if possible at all, clearly would not occur until after the decree’s legal expiration on April 20. But the Kadet deputies wanted to take action, and the field courts martial issue seemed the politically most promising area of activity. Maklakov joined the repeal effort enthusiastically, though he later regretted the strategy. In hindsight he believed that joining with the left in this way made the Kadets appear to be its allies in support of revolution.19 Nonetheless, the repeal effort was the occasion of one of his most famous speeches in the Duma, and indeed the one of which he seems to have been most proud. We have already seen part of the speech in discussing his relationship with Tolstoy—Maklakov’s assault on the death penalty.

His speech rested primarily on rule-of-law ideals. Stolypin had argued that, in the interests of protecting the state from the revolution, it was sometimes necessary to sacrifice private interests. Maklakov turned this around, depicting the field courts martial as destructive not merely of private interests but also of the state itself. Anticipating the words later put into the mouth of Sir Thomas More by the playwright Robert Bolt in A Man for All Seasons, he said:

Striking at the revolution, you have not struck private interests but have struck all that protects us, the courts and lawfulness. . . . If you defeat the revolution this way, you will at the same time defeat the state, and in the collapse of revolution you will not find a rule-of-law state but only solitary individuals, a chaos of state breakdown.20

He closed by saying that, if the government really meant to bolster the state system, as Stolypin had claimed, it should join those in the Duma attacking the field courts martial, and, not waiting for the decree to expire automatically, should itself declare that “the shame of killings by field courts martial in Russia will cease.”21

In response, Stolypin acknowledged the legal merits of his Kadet critics’ attacks, mentioning Maklakov by name, and going so far as to say that if he pursued that avenue he likely would not disagree with Maklakov.22 But he offered the defense of necessity. He pointed to declarations by the revolutionary parties calling for uprisings, which of course were occurring, albeit in a scattered way. And, as we’ve seen, assassinations were running at a pace no government could tolerate. His speech ended by proposing some sort of accommodation with his critics:

[T]he government has come to the conclusion that the country awaits from it not evidence of weakness but evidence of confidence. We want to believe that we will hear from you, gentlemen, a word of pacification, that you will cut short the bloody madness. We are confident that you will say those words that will have us all begin—not the destruction of the historic edifice of Russia—but its recreation, its restructuring, and its enhancement.

In expectation of that word, the government will take measures to limit this severe law solely to the most extreme cases of the most audacious crimes, so that when the Duma directs Russia to peaceful work, this law will fall, simply by not being introduced for confirmation [under Article 87].23

The meaning of this offer may not have been altogether clear, but on its face it looked like a commitment to extinguish the activities of the field courts martial before their legally predetermined end (at least for all but extreme cases), in reliance on Stolypin’s hope or expectation of some word from Duma members, at least from the Kadets, condemning revolutionary violence.

No such word came. Rather, the Kadet leadership treated this apparent olive branch as a stink bomb.24 But Stolypin’s meaning is to some degree independently verifiable by looking at the behavior of the field courts martial after March 13. The Social Democratic paper, Tovarishch, hardly an organ to downplay the state’s bloodletting, collected the month-by-month figures.25

The downward trend is clear. It had been under way since November, but the decline steepened sharply in February, March, and April. Without day-by-day figures, and indications of the crimes for which the field courts martial were used after March 13, we can’t precisely evaluate Stolypin’s fulfillment of his apparent promise.26 But despite those gaps and the preexisting decline, the record appears at least consistent with an effort to confine use of the field courts martial to the most egregious cases. Although the courts were sure to expire in any event (subject, of course, to the risk that the government might dissolve the Duma and radically limit the franchise, as it in fact did on June 3, 1907), this is a case where Maklakov’s eloquence in the Duma may actually have saved lives from government arbitrariness.

In a letter to his friend Boris Bakhmetev, the Provisional Government’s ambassador to the United States (unlike Maklakov, Bakhmetev at least arrived in time to take up the office), Maklakov said that the speech was the only one for which he received laurels in the press (an absurd exaggeration!), but that for him

what made it important was not articles in the press . . . nor applause in the Duma; for me the important thing was the response of adversaries. I’ll not forget how at the time of the speech I turned toward Stolypin, sitting on the ministerial bench, and saw his eyes, which he never took away from me. I continued to watch his eyes, and he didn’t turn them from me till the very end; I was later told that he had talked about me afterwards. And the speech . . . was built on respect for authority, on the need to preserve it from what was dangerous for it, to save it from any mistakes that might compromise it. This was the idea that I pursued to the end, on account of which I often found myself divided from the Kadets.27

While the field courts martial decree itself was lawless, the authorities managed to make it more lawless by violating even the decree’s own rules. In his speech assailing the decree, Maklakov exposed an especially flagrant example. Four people from the countryside surrounding Moscow met another outsider, who was a policeman. They asked him to join them, and all five spent several hours eating and drinking and in friendly conversation. After a while the policeman departed. The four then drank some more, and, perhaps drunk, wandered through the city and again met their friend. They asked him to rejoin them, but he refused, and they then began to fight with him, to drag him about by force. The policeman waved a revolver at the four. One of the four picked up a wooden snow shovel that was lying about and struck him on the head (as we’ll see, the policeman died, but only after government injustice had run its course). All four were brought to a police station, sobered up, overslept, and, the next day, heard to their horror that they had been given over to a field court martial.

The members of the court expected something more like sedition and were amazed when they saw four bearded old people before them. They were horrified by the recognition that under Article 18 of the field courts martial decree there was only one punishment—the death penalty. They realized that death was impossible for such a fight. Although unable to state a legal justification for their verdict, they invoked the absence of aggravating circumstances, and sentenced the four to hard labor for an indefinite term, thinking it a punishment that no one could criticize as too soft.

They were wrong. Moscow’s governor general, Sergei Konstantinovich Gershelman, overturned their decision. The verdict was put before him at ten in the morning, and at noon he cancelled it. In the evening he began another field court martial, condemned the four to death, and promptly had them hanged. Forget, for a minute, the savagery of Gershelman’s decision: Article 5 of the field courts martial decree itself forbade any reversal of the court martial’s judgment. But when an official found the rule inconvenient, he simply disregarded it.

As part of the October Manifesto’s promise that Duma members would get “an opportunity for actual participation in the supervision of the legality of [officials’] actions,” the Fundamental Laws entitled Duma members to question officials on the floor of the Duma. Maklakov thus pursued the attack on several occasions, asking for an explanation and responding to official efforts at justification. Among the official defenses was that the injuries inflicted on the policeman were more severe than Maklakov had originally reported—indeed, he had ultimately died of them. But the death occurred after the second trial, and thus in no way excused the government’s lawlessness. Officials also cited legal exceptions, which Maklakov showed were inapplicable. The most extreme claims were those of Ivan Shcheglovitov, the minister of justice, and Alexander Makarov, then deputy minister of internal affairs, who would ultimately become the minister and Nikolai Maklakov’s predecessor in that post. Shcheglovitov argued that there had been no unlawful reversal of a verdict; the first one had only been put aside without implementation! Makarov went further: Gershelman didn’t reverse any verdict because the one he was accused of overturning did not, legally, even “exist.”

Writing of the episode later, Maklakov drew the lesson that use of the Duma’s interrogation weapon worked best when not entangled with a factual dispute, for which the Duma was illsuited. (His account in the Duma had been inaccurate as to the scope of the policeman’s wounds, but the error was irrelevant to the government’s offense.) It was best, he thought, to focus on conduct that was unlawful even on the government’s version of the facts. This particular exchange, he thought, brought an act of government illegality into the open under the scrutiny of the Duma. It made clear that the government could not defend itself with straight arguments, but rather was reduced to lies, sophistry, and demagogy—such as the theories vaporizing the first verdict. Stolypin’s defense of state necessity was plainly unavailable.28 Many of Maklakov’s later Duma speeches pursued the same basic strategy.

Before turning to the Duma’s demise and Maklakov’s efforts to avert it, a word is in order about the Second Duma’s treatment of two issues that had bedeviled the First: amnesty and terror. As to amnesty, the Kadets recognized that they had a jurisdictional problem: the Fundamental Laws (Article 23) assigned that power to the executive. But, wishing to press the issue, they placed it on the agenda but then proposed to send it to a committee to review the jurisdictional question. Maklakov spoke energetically for the referral to committee. He thought it clear that the tsar’s power was exclusive as to the verdicts of ordinary courts, but very likely the reverse as to administrative decisions under the extraordinary security laws. He argued to the Duma that the committee could use the referral to develop a law eliminating altogether the system of administrative exiles and fines under the extraordinary security laws.29

As to terror, Maklakov seems not to have been very active. The Duma as a whole floundered. Its chairman, the Kadet Fyodor Golovin, succeeded for a long time in keeping it off the agenda, reflecting the Kadet concern that a resolution condemning terror would be seen as an implicit approval of the field courts martial and a betrayal of the left, while a negative vote would enable the government to paint them as sympathetic to terror. Maklakov worked to forge a compromise resolution acceptable to both the government and the Kadets, but the effort misfired.30 There followed a swirl of draft resolutions, many aimed at trying to satisfy both sides by including a condemnation of the Black Hundreds’ terrorist acts, which in at least some cases had been assisted by elements in the government. None passed. Looking at the issue in hindsight, Maklakov argued that, whereas the First Duma’s failure to condemn terror had not been justifiable, the Second Duma’s was. By that time, he thought, the government’s own methods, including its use of agents provocateurs, were so offensive that any resolution should reach them as well. Of the rightists’ arguments, he wrote, “They demanded condemnation of terror not in the name of the rule of law, but in support of the government.”31 Given that the authority for the field courts martial expired in April, that left-wing terror continued to predominate over right-wing or government-supported terror, and that the Kadets kept silent on left-wing terror even in their own newspapers (where they could have added balance in their own words),32 the pass he gives the Kadets seems a stretch.

Although the divisions over amnesty and terror were severe and even raucous, the Duma-government split over agrarian policy was perhaps the key reason for the government’s dismissal of the Duma and abrogation of the franchise. The government’s solution to the problems of peasant agriculture was to establish, through its decree of November 9, 1906, a means by which peasants, acting either collectively as an entire village,33 or individually against the will of the village, could convert communally owned property into individual “personal property,” a status akin to conventional Western private property.34 Fully converted land would be free from periodic redistributions to match up landholdings with family size and would be consolidated rather than scattered so that an individual peasant could cultivate it independently rather than only with the agreement of all the peasants in his commune. A peasant would no longer be, vis-à-vis the commune, in a phrase that Maklakov attributed to N. N. Lvov, “a rightless individual against a tyrannical crowd.”35 The Kadet proposals took exactly the opposite tack on private property: the first step was confiscation of gentry land at a value that was never specified but that was explicitly not fair market value. Their second step was to hold these lands as part of an ill-defined national land fund, to be allocated to peasants in some sort of equally ill-defined temporary tenancy, evidently subject thereafter to continuous bureaucratic reallocation.36 Miliukov explicitly took the view that peasants simply wanted land and were not interested in the legal regime under which they held it.37 The argument confirms Leonard Schapiro’s comment that Miliukov’s tragedy was “that he believed that he was a liberal, when he was in reality a radical.”38

The government’s concern was not that the Kadet program would become law. It could easily prevent that by having the State Council reject, or ignore, any Duma bill. The risk was that the Duma could destroy the government’s program, dependent as it was on a decree under Article 87. For such a decree, all that was needed was for the Duma to vote it down.39 With an anticipatory dismissal of the Duma therefore looming as a possibility, Maklakov was open to participating in a direct conversation with Stolypin. The background of the conversation, the conversation itself, and the reactions from left and right, tell us a good deal about the state of politics in 1907 Russia.

The first contact with Maklakov on the subject came through a Kadet member of the First Duma, S. A. Kotliarevskii, who had signed the Vyborg Manifesto out of party discipline although he thought it inexcusable. Because of the government’s prosecution of the signers, he was therefore not in the Second Duma. He favored Kadet relations with cabinet members whose goodwill he trusted, such as Stolypin and Alexander Izvolskii (the foreign minister); he unexpectedly asked Maklakov if he’d be willing to meet with Stolypin. Maklakov saw nothing reprehensible in such a meeting and said he was willing. Kotliarevskii later called him to the phone; Stolypin was on the line, and they had a brief, rather guarded conversation. Maklakov surmised that Stolypin thought the phone was likely bugged. The next day Maklakov received a note of invitation, and met Stolypin that evening at the Winter Palace.40 Maklakov discussed the meeting only with the Kadets ideologically closest to him—Mikhail Chelnokov, Pyotr Struve, and Sergei Bulgakov. In classifying them, it’s useful to recall that Maklakov and the other three were among the eight Kadets who had attacked the field courts martial decree, something that only one Octobrist had done (Mikhail Kapustin); so the four were by no means reactionaries. (Struve and Bulgakov were later among the contributors to Vekhi, the collection of essays that assailed the Russian intelligentsia’s rigidity, utopianism, and absorption in vague abstract principles.) The four nonetheless jokingly called themselves (and were called) the Black Hundreds, or the Black Hundred Kadets.41

Each of the four had occasional meetings with Stolypin after Kotliarevskii raised the issue, though only Chelnokov saw him at all regularly—in his capacity as Duma secretary.42 At one such meeting, Stolypin made clear his anxiety about secret meetings of a Duma committee on agrarian matters, which he feared were building up to a rejection of the November 9, 1906, decree; Stolypin indicated that if rejection loomed, the government would dismiss the Duma preemptively rather than waiting for such a rejection.43 The four moderates evidently caucused. Struve understood from a meeting with Stolypin that the latter would accept a good deal of amendment of the decree as a way of avoiding dismissal of the Duma, but not its transformation into a program of massive compulsory alienation—just the sort of measure that Kadet party rhetoric, and its agrarian appeal in the First Duma, had appeared to endorse.

The four met and agreed that the best strategy would be to ensure that any bill would receive a clause-by-clause reading: immersion in detail might lead to moderation. Chelnokov saw Stolypin and returned quite relaxed, conveying the impression that such a process was acceptable to Stolypin.44 The premise appears to have been that Duma adoption of a radically amended version of the November 9, 1906, decree would constitute a rejection within the meaning of Article 87—and that seems a reasonable interpretation of the article. Thus amendments would meet Stolypin’s demands only if they were moderate enough to allow him to get the amended version approved by the State Council and tsar.

Soon afterward, on May 10, 1907, Stolypin gave an extensive speech in the Duma on agrarian policy. Among other things, it discussed his agreement to compulsory alienation to help peasants use their land: to create wells and cattle pathways to pasture, to make roads, and finally to cure the scattering of plots. If the suitable Duma committee asked government representatives to attend, they could offer more details.45 Maklakov himself thought that one might reasonably add instances of land that a peasant rented or that wasn’t in use.46 Given landowners’ widespread practice of renting out land, it seems naïve for Maklakov to have thought that this would not be a deal-breaker.

In Rech, the newspaper edited by Miliukov and generally seen as the voice of the Kadet party, Miliukov responded to the Stolypin speech in his customary vein, saying that the proposal didn’t deserve the name of compulsory alienation (curious that that should have transmogrified itself into an end rather than a means!) and was just a lie. The only object was to raise the price at which landowners could sell their land.47

Maklakov and his confederates now believed that the key was to ensure that the Duma as a whole didn’t issue directions to the agrarian affairs committee that would be seen by Stolypin as likely to completely frustrate his goals. On May 26 this was achieved: the Duma voted 239 to 191 for a referral to committee without instructions (that is, without any specific mandate that the government might have read as foreshadowing rejection of its agrarian reform decree). Whether the Kadets and their allies to the left could have restrained themselves enough not to kill Stolypin’s agrarian program under Article 87 seems at best questionable; even Maklakov’s moderate Kadet ally Ariadne Tyrkova-Williams thought that in envisaging possible compromise he preferred “the wish to the reality.” But as the four saw it, the only drawback was that the debate had included reminders of prior votes for compulsory alienation.48 Overall, they saw the Duma’s debate and action as meeting Stolypin’s concerns well enough to save the Duma from dismissal.

Then on June 1 Stolypin asked for a closed session of the Duma and used the occasion to assert a claim that some Social Democratic deputies had been involved in terrorist activities. He asked the Duma to agree to the arrest of those involved and the removal of all the other Social Democrats from the Duma. The Duma set up an investigative committee that included Maklakov. Although the committee asked for more time to examine the allegations, it essentially found the government’s claim baseless.49 Meanwhile, back-channel contacts led to a meeting of the four moderates with Stolypin at 11:30 on the night of June 2. Stolypin met them immediately on their arrival, even though he was in the middle of a Council of Ministers meeting. After some general discussion of whether the Duma was working responsibly, Stolypin said there was one issue on which agreement was impossible—the agrarian one. The four were shocked; they thought they had worked out a possible path to agreement. As recounted by Maklakov, it appeared that Stolypin either mistakenly believed that the committee had adopted a resolution favoring mass compulsory alienation, or misunderstood the consequences of what had occurred, and thus was unaware that a procedure had been adopted that the moderates believed could yield an acceptable outcome. But Stolypin asked many questions, appeared to respond favorably to the answers, and gave the impression that their arguments had now removed this ground for dismissing the Duma—the main one, as it had appeared.50

Stolypin then turned the conversation in a wholly new direction, asking the four Kadets why they couldn’t agree to remove the Social Democrats. “Free the Duma from them, and you will see how well we’ll get along.” Maklakov replied for the group, saying that Stolypin’s demand was so extreme that “it would be shameful for us to look at each other if we accepted it.” Stolypin asked, “So the Duma will refuse us?” Maklakov answered, “Probably. I am the most right-wing Kadet and I will vote against you.” Stolypin: “Then there is nothing to be done. Only remember what I say—you have just dismissed the Duma.”51

What can one make of this? Maklakov appears convinced of the sincerity of Stolypin’s hopes for a compromise on the agrarian question, but we know with reasonable confidence that the tsar was by then emphatically eager to get rid of the Duma. A high government functionary, Pyotr Shvanebakh, reports being present with Stolypin late in the night of June 2 and hearing of a call from the four Kadets that they were interested in meeting him. All present “urged Stolypin not to lose time with the Kadet emissaries,” but he rejected their advice and talked with the Kadets, by Shvanebakh’s account, till 2:00 in the morning. After they departed, the group continued to wait. Soon a messenger from the tsar’s Peterhof residence arrived, delivering documents signed by the tsar to change the electoral law, accompanied by a letter saying that he had waited all day for news of the dismissal of the “accursed Duma.” He had sensed that something had gone wrong, and declared: “This is impermissible. The Duma must be dismissed tomorrow, Sunday morning. Decisiveness and firmness.”52 According to the American ambassador, the tsar had two weeks earlier told Sir Donald Mackenzie Wallace (a British observer who had been at times a journalist, at times a government official) that he intended to dissolve the Duma.53

Thinking their visit was not an official party act, the four Kadets had not told their colleagues about it. But S. D. Abelevich, a journalist for the left-wing daily Rus, had evidently been tipped off by the minister of trade and ran a story accurately reporting the Kadets’ explanation of why they couldn’t agree to hand over their Social Democratic colleagues. But Abelevich embroidered a bit, claiming that the visit somehow portended “some new combination the details of which are not known as yet.”54

Just as Stolypin’s colleagues had urged him not to bother with the four, their fellow Kadets—armed with the Abelevich article—at best scoffed at the failed mission, at worst regarded it as treacherous. Iosif Gessen, for example, writing years after the event, focused on the supposed terrorism of the accused Social Democratic deputies, and thought it absurd to hope that Stolypin would drop his demand to arrest them.55 The furor in the party was such that Maklakov went to Miliukov and offered to resign; Miliukov, to his credit, refused and in fact calmed the others.56 But Struve took the party outrage hard. It “struck him as symptomatic of an utterly self-destructive mentality,” and drove him largely out of active party politics.57

It seems clear that well before the meeting the tsar had decided not only to dismiss the Duma but also to execute a coup d’état, unilaterally changing the electoral law (he did, on June 3, 1907). Stolypin and the tsar, however, were not identical, and it’s entirely possible that Stolypin remained open to some saving change of events. But we have to consider his state of mind in the run-up to June 2. He could easily have been convinced, by earlier Kadet rhetoric and votes, and by behavior such as Miliukov’s denunciation of his May 10 speech, that the Kadets (and obviously the revolutionary deputies to their left) would not compromise on agrarian reform. On that premise he agreed to implement the tsar’s wish to dismiss the Duma (and to transform future Dumas by a unilateral change in the electoral system), proceeding by means of the bogus attack on the Social Democrats. By June 2 his apparent price—Duma acceptance of the removal of the Social Democrats and of the mythical plot—was obviously too high for Kadets with honor and commitment to the Duma as the pillar of a constitutional regime. But that hardly shows that he was acting in bad faith when he parlayed with them. Yet, even if the four moderates had convinced him on the night of June 2 that an acceptable solution on agrarian reform was possible, there was probably no arrangement that would have enabled Stolypin to withstand the tsar’s commitment to radical, lawless action.

The Act of June 3 changing the electoral law was indeed lawless. The tsar purported to adopt it under Article 87, but that article expressly excluded its use for any change in the election laws for the State Council or the Duma. And the change was drastic, ensuring a strong majority of what the regime viewed as “trustworthy” representatives. Large geographic swaths of the country, such as Turkestan, lost representation entirely; the representation of the 11 million Poles fell from 46 deputies to 14; in the fifty-one provinces of European Russia, landowners would get almost 50 percent of the “electors”—the persons who in the layered system would actually cast the votes for deputies—against 26.2 percent for the urban population and 21.7 percent for peasants. In the countryside the tiered system assured that peasants reaching the status of elector would vote under the watchful eyes of landowners.58 Of course this system produced, as intended, Dumas inclined to reach agreement with the government (at least relative to the First and Second Dumas). But the skewed franchise, and that franchise’s unlawful origins, exacted a price in government legitimacy right through to 1917, when they impaired the Fourth Duma’s ability to take over from the faltering Nicholas II.

An unbridgeable gulf between two of a country’s institutions—as manifested in the June 3 coup—is hardly either novel in politics, or necessarily fatal to either institution. What was most ominous for Russia is surely that the dominant opinion on both sides regarded even talking with their political opponents as a worthless activity, or worse.

How did Maklakov view the coup? He is quite explicit in his memoirs that, despite his vigorous criticism of the Second Duma, he believed that in it the left had tempered the bellicose tactics of the First Duma, and that responsibility for the failure to fulfill the chance of implanting a constitutional monarchy fell squarely on the regime.59 I’ve encountered nothing by him that might seem to excuse the government. Yet Soviet historians, ever reluctant to impute true constitutionalism to a “bourgeois” public figure, have latched onto observations by Maklakov on the floor of the Duma citing the 1762 coup removing Peter III and bringing Catherine to the throne, and the 1801 coup removing Paul and elevating Alexander I, as evidence of a belief that coups can lead to good. True enough. But his whole point in these passages was to distinguish those illegalities from a recent Duma act, which he regarded as not only unconstitutional (for infringing on Finland’s constitutional liberties) but also likely to bear corrupt fruit.60

Maklakov had developed the same theme in an earlier article on the rule of law in Russia, noting instances when a legally invalid act is politically accepted, receives recognition, and becomes the law. He cited not only Catherine II’s seizure of power but also the overthrow of Louis XVI in 1792 and of Napoleon III in 1870. (Americans might amplify the record by pointing to their own constitutional convention: given only a mandate to propose amendments for the Articles of Confederation, it drafted an entirely new constitution.) He specifically considered the June 3, 1907, coup, focusing on its juridical defects: although Stolypin explicitly defended the act as a coup, the government pretended, by cloaking it in Senate approval, to rest on a supposed continuation of the Senate’s role of verifying legislation for failure to comply with the Fundamental Laws.61 In his Duma speech and in the article Maklakov recognized the possibility that a coup d’état can “work,” but he never suggested that the June 3 decree represented such a coup.

In assessing Maklakov’s take on the core period of the Revolution of 1905, from Bloody Sunday in January 1905 to the June 3, 1907, coup, we have to distinguish between his acts during that period and his later analysis. While the validity of his analysis doesn’t depend directly on when he reached it, contemporaneous parallel assertions would surely buttress it—the reverse for contemporaneous contradictions.

On some issues there were clear changes. His spring 1906 memo to French officials savaged the State Council’s legislative role, which in State and Society he found quite harmless. And in articles published in Russkie vedomosti shortly before and during the First Duma itself, and in speeches pursuing election to the Second Duma, he seemed to endorse parliamentary supremacy almost as insistently as his more extreme Kadet peers. He scoffed at moderates who “don’t recognize ministerial responsibility [to the Duma], who disown parliamentarianism.” He even gave favorable mention to Nabokov’s “pithy” summary of the parliamentary principle, which he later anathematized.62 His early comments show no sign of the point he made later—that as the Duma manifested responsibility and usefulness, government responsibility to it would follow in the course of nature, as it had in Britain.63 Giving a campaign boost to such a change, of course, is hardly the same as making it a precondition to substantive legislative work—the Kadets’ strategy in the First Duma.

Indeed, his good friend and fellow moderate Kadet Ariadne Tyrkova-Williams noted in her diary on first reading State and Society: “Even Maklakov himself, as I recall, in the Duma and the Central Committee of the Kadet party, didn’t speak against its [the party’s] policies, and only after the events did these criticisms with which his memoirs are full come to mind.”64

Her diary (plus the published records of the Kadet party) seem enough to convict Maklakov at least of failing to press his case in the party. So we have no way to be sure of his contemporaneous thoughts. But there are clues that they didn’t change all that much, especially after the promulgation of the Fundamental Laws. His attack on the field courts martial decree in the Second Duma rested on its threat to the rule of law in Russia, and even his early response to the violence after Bloody Sunday proposed pitching any Beseda reaction as an attack on the regime’s own lawlessness. And his meeting with Stolypin to save the Second Duma shows a readiness—at some risk to his position within the party—to seek common ground with opponents in the regime. His public posture was generally consistent with his later analysis.

We can learn something from a public debate between Miliukov and Maklakov that they conducted as émigrés in Paris, in a newspaper edited by Miliukov and a “thick” journal—the sort of intellectually (and physically) weighty periodical that dated from tsarist times. Maklakov had published the essence of State and Society in such a journal, and Miliukov replied both there and in an émigré daily that he edited. Throughout, Miliukov reproached him for the unrealism of his arguments (as he saw the matter), not for flipping his position.65 Moreover, in his insistence on the inadequacy of the October Manifesto and the Fundamental Laws, Miliukov never attempted a comprehensive assessment of either document in constitutional terms. He thought it enough to say that they left in place the three “locks” (the State Council, the absence of four-tailed suffrage, and the absence of ministerial responsibility to the legislature), locks which he said “blocked the lawful path to construction of a normal constitutional regime.”66 But this critique is simply a restatement of the Kadets’ constitutional goal, and an assertion (doubtless true) that the Fundamental Laws fell short of that benchmark. It tells us little about the scale of the change wrought by the two documents (on paper, to be sure) or about their capacity to generate improvement. This is odd, since only deficiencies along these lines could justify his response that “nothing has changed” and thus the Kadets’ behavior in the First Duma. We are left to guess his argument as to why the two, evaluated as constitutional documents, did not represent not only a tectonic shift in tsarist policy but also a promising platform for the development of liberal democracy.

Beyond the supposed deficiencies in the documents, Miliukov’s argument rested largely on the lack of any sincere commitment to constitutionalism on the part of the tsar and his ministers. He often mentioned Nicholas II’s resistance to the word “constitution,” as reported to Miliukov by Witte.67 And he pointed to another clue to Nicholas’s attitude—his well-known belief, based in part on a rather wishful assumption of unity between tsar and people, that it was his duty, in the interests of the people, to pass the autocracy on to his son more or less unimpaired.68

Of course the dispute between the tsar and society was over more than the word “constitution.” The tsar’s distaste for the word reflected his loathing for the thing itself. But while it is undoubtedly a plus when the author of a state document is sincerely committed to its undertakings, sincerity is hardly a sine qua non of effectiveness. After all, the October Manifesto was effective in producing action on the tsar’s part—promulgation of the Fundamental Laws themselves. And when Englishmen and their successors over the centuries asserted rights in the name of Magna Carta, no one asked whether King John was “sincere” at Runnymede, or whether later kings “sincerely” accepted his commitments (which were thereafter embodied in English statutes). It seems improbable that such verbal commitments can ever do more than nudge the balance toward compliant behavior. As Learned Hand once said,

I often wonder whether we do not rest our hopes too much upon constitutions, upon law and upon courts. These are false hopes, believe me, these are false hopes. Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it; no constitution, no law, no court can even do much to help it. While it lies there it needs no constitution, no law, no courts to save it.

Though Hand surely exaggerates, the basic idea is correct. Unless society has internalized the norm and is willing and able to exert pressure, holders of power will get away with violations. But a document can help on both counts—internalizing the norm and energizing society. The signer’s state of mind is hardly a be-all-and-end-all.

In the end, what was the essence of the political difference between Maklakov and Miliukov? There was, surely, a difference in their weighting of the “liberalism” and the “democracy” in liberal democracy. Maklakov’s great goal was control of government arbitrariness, Miliukov’s the establishment of majoritarian democracy. This surely accounts for some of the higher value that Maklakov placed on the October Manifesto and the Fundamental Laws. But the far greater gap seems to me to lie in their ideas of the path toward liberal democracy from the centuries of Russian autocracy. Maklakov saw it as a long, hard slog, a gradual overcoming of the autocracy’s near millennium-long deformation of Russian ways of thought. Miliukov saw it as something that a wise tsar could have accomplished in a minute, either by summoning a constituent assembly elected by four-tailed suffrage or by directly proclaiming a copy of the Belgian or Bulgarian constitution. The two men seem to be latter-day personifications of Edmund Burke’s gradual reformism and Thomas Paine’s revolutionary commitment to “reason” and its teachings.69