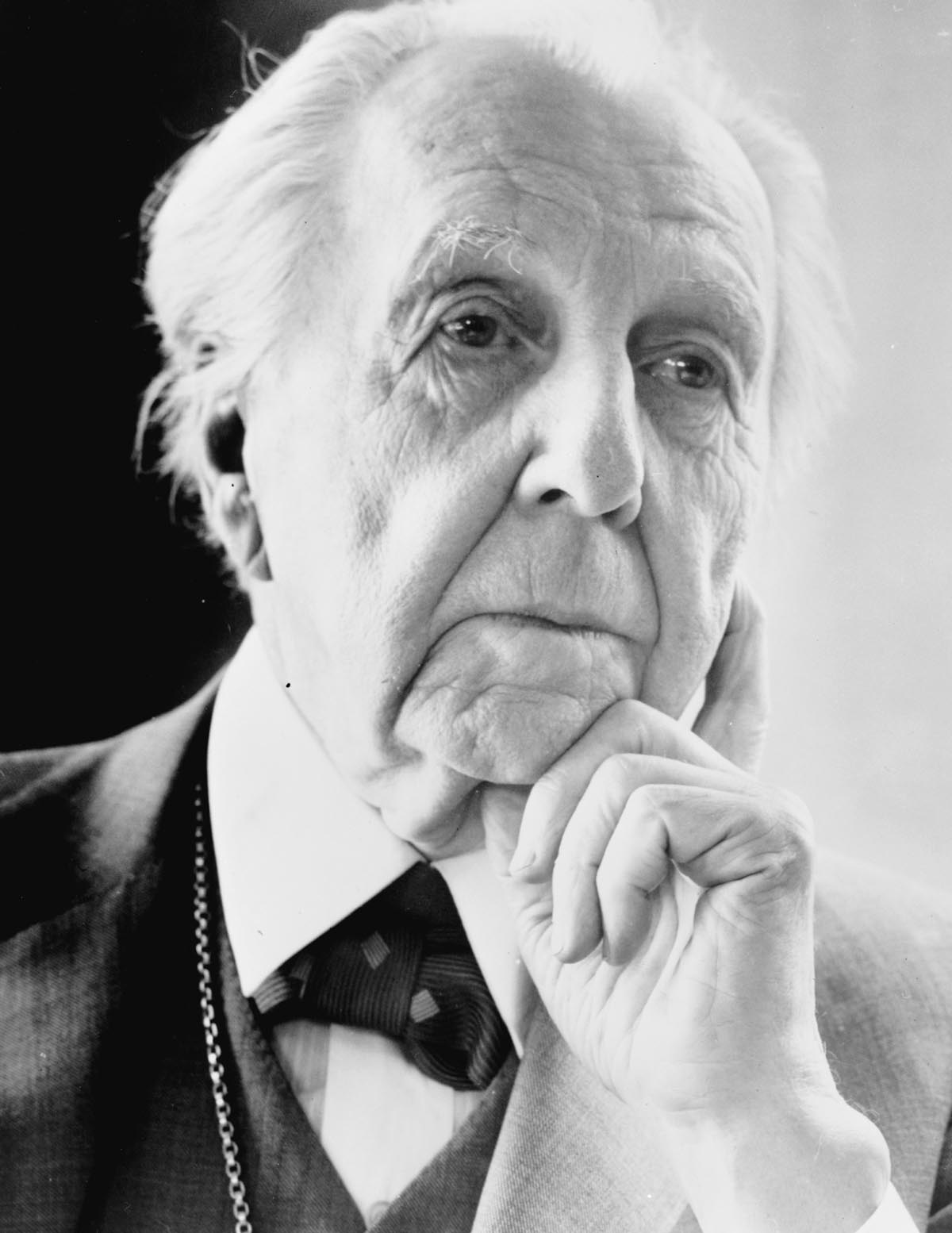

FIG. I Frank Lloyd Wright in a contemplative pose, shortly before construction began at the Guggenheim Museum. (New York World-Telegram & the Sun newspaper Photograph Collection, Library of Congress/Prints and Photographs)

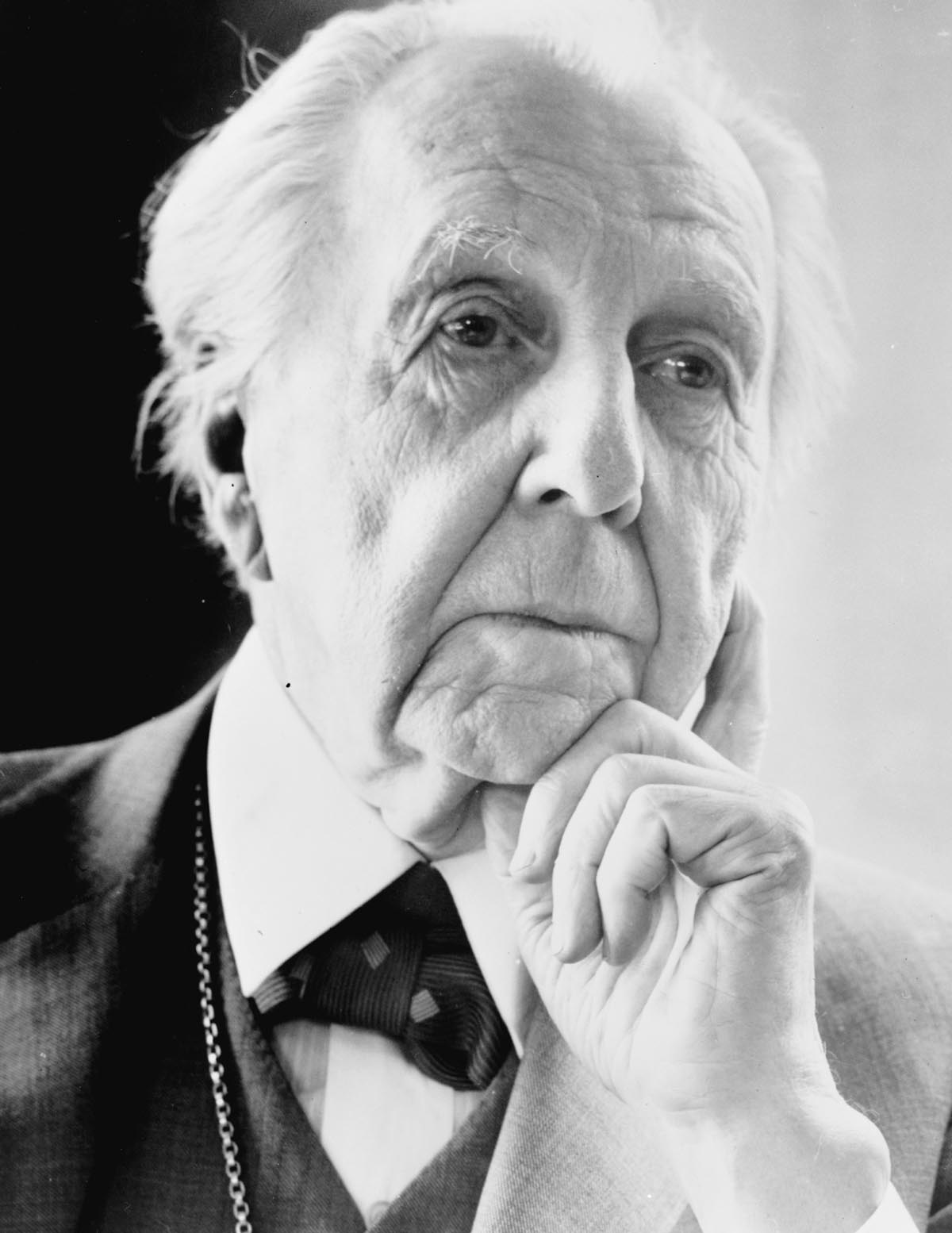

FIG. II Philip Johnson, Post-Modernism’s Moses, with his tabletlike model of the AT&T Building, in the image used on the cover of the January 8, 1979 issue of Time. (Ted Thai, The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

FIG. III Wright’s rambling homestead near Spring Green, Wisconsin, famously set at the brow of the hill and reflected here in the placid waters of the man-made pond. (Roger Straus III)

FIG. IV For Wright, Taliesin was an architectural laboratory, a place for testing his ideas. The “bird walk,” a forty-foot cantilevered terrace that extends into space like a great diving board, anticipated the broad “trays” he incorporated into his design for E. J. and Lilian Kaufmann. (Roger Straus III)

FIG. V As seen from the meadow below, here is Miës’s restored Tugendhat House with its defining horizontal band of tall windows. (Donald Gellert)

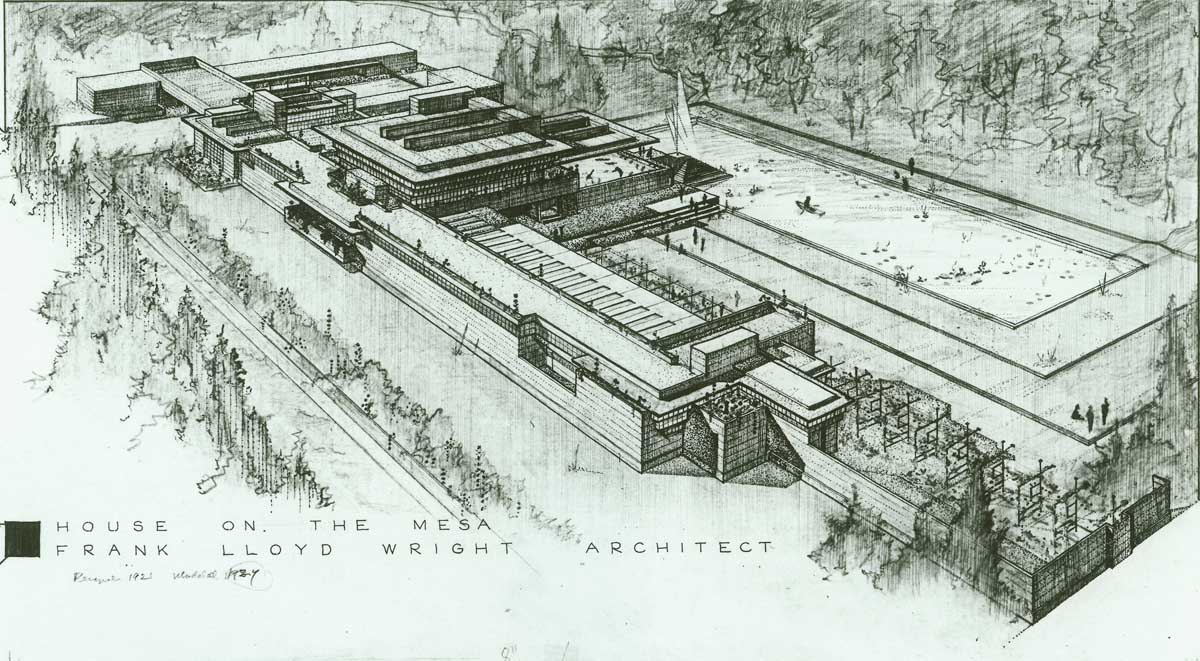

FIG. VI A perspective drawing of Wright’s House on the Mesa, which was displayed at the 1932 Modern Architecture: International Exhibition. Although Wright recycled some of its elements over the years, this design was never constructed. (The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation/Art Resource, NY)

FIG. VII Wright’s desert village, dubbed Taliesin West, in the Sonoran Desert in Arizona. (Roger Straus III)

FIG. VIII For Philip Johnson, Wright’s Taliesin West was the perfect exemplar of what the younger man called the “processional element in architecture,” inviting the visitor to enter, engage, and experience the place. (Roger Straus III)

FIG. IX Wright’s first rendering of Fallingwater, from the ground up, hurriedly sketched, on September 22, 1935, as E. J. Kaufmann motored toward Spring Green for lunch. (The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives, the Museum of Modern Art/Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University)

FIG. X Not only its terraces but even the stairs to the stream are suspended above the waters of Bear Run. (Roger Straus III)

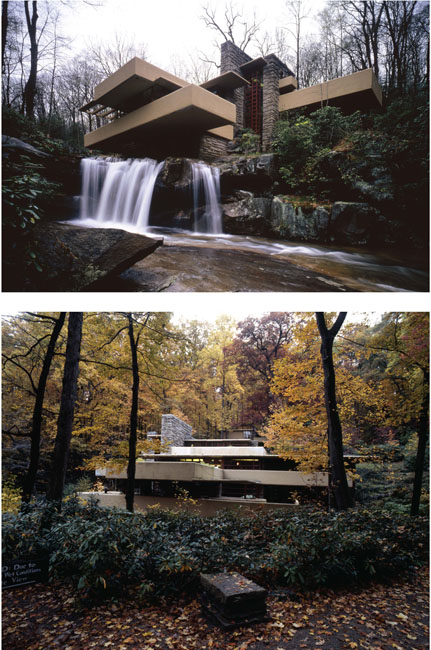

FIG. XI and FIG. XII Fallingwater’s extraordinary changeability is clear from these two images. One echoes the from-the-streambed composition of Bill Hedrich’s classic 1937 shot of Fallingwater (above); the other conveys something of the experience the visitor has upon approaching the house via the access road. (Roger Straus III)

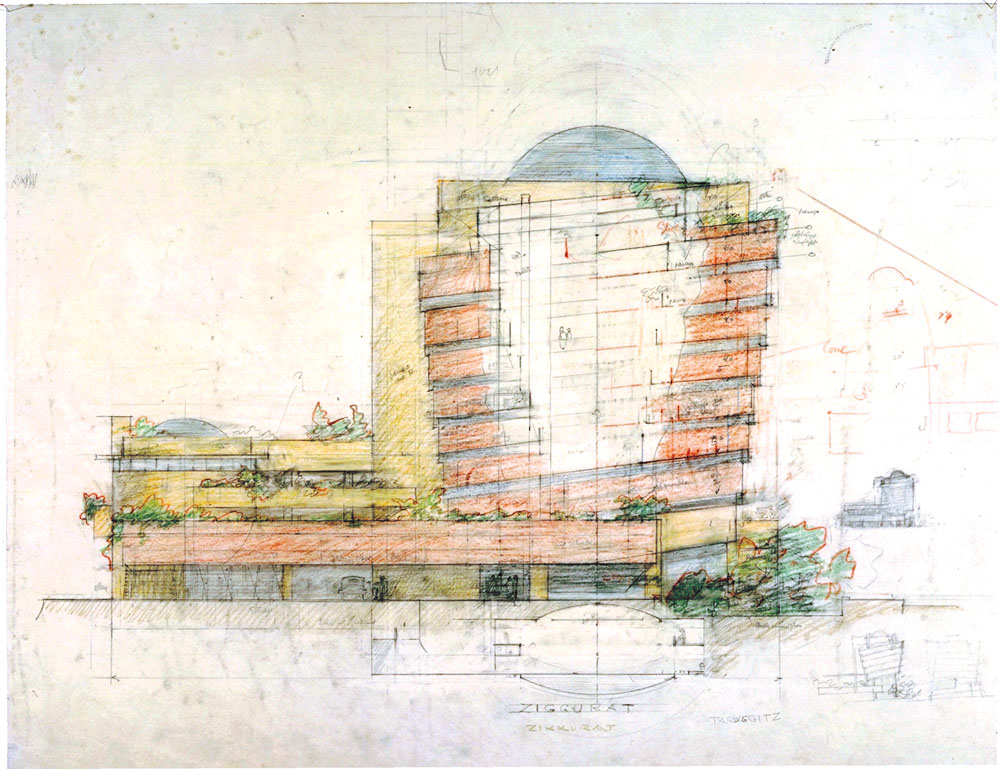

FIG. XIII Wright’s detailed early drawing of the Guggenheim Museum, which is both an elevation and a section. Note the word ziggurat and the little thumbnail views in the detail, below. (The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives, the Museum of Modern Art/Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University)

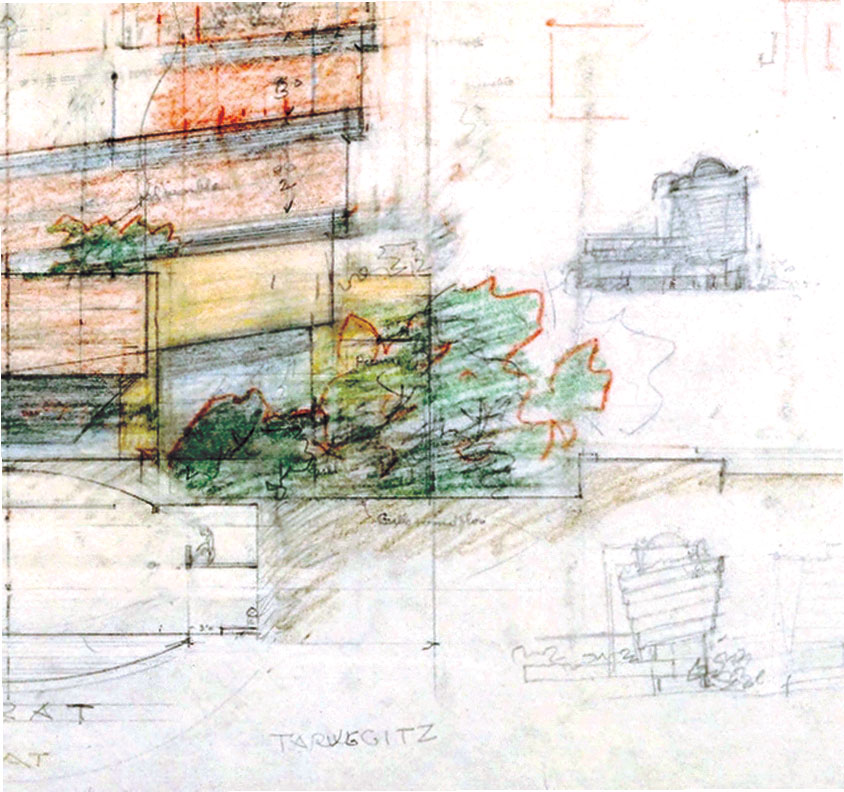

FIG. XIIIa

FIG. XIV By late autumn 1957, the museum had risen well above the construction fence that lined Fifth Avenue. (Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc., Library of Congress/Prints and Photographs)

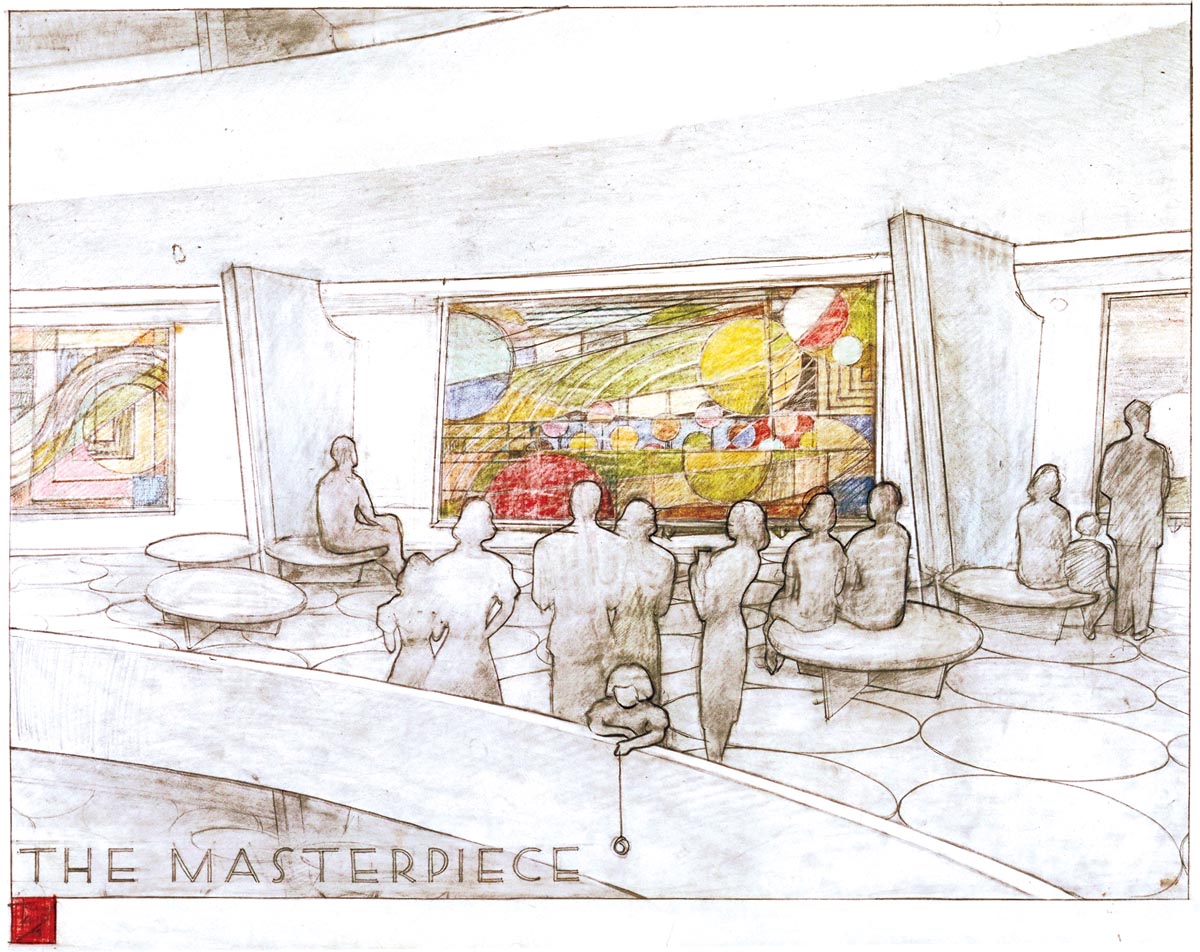

FIG. XV Wright’s (and draftsman Ling Po’s) drawing titled “The Masterpiece,” dating to 1958, with the yo-yo girl leaning into the Guggenheim’s great rotunda. (The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives, the Museum of Modern Art/Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University)

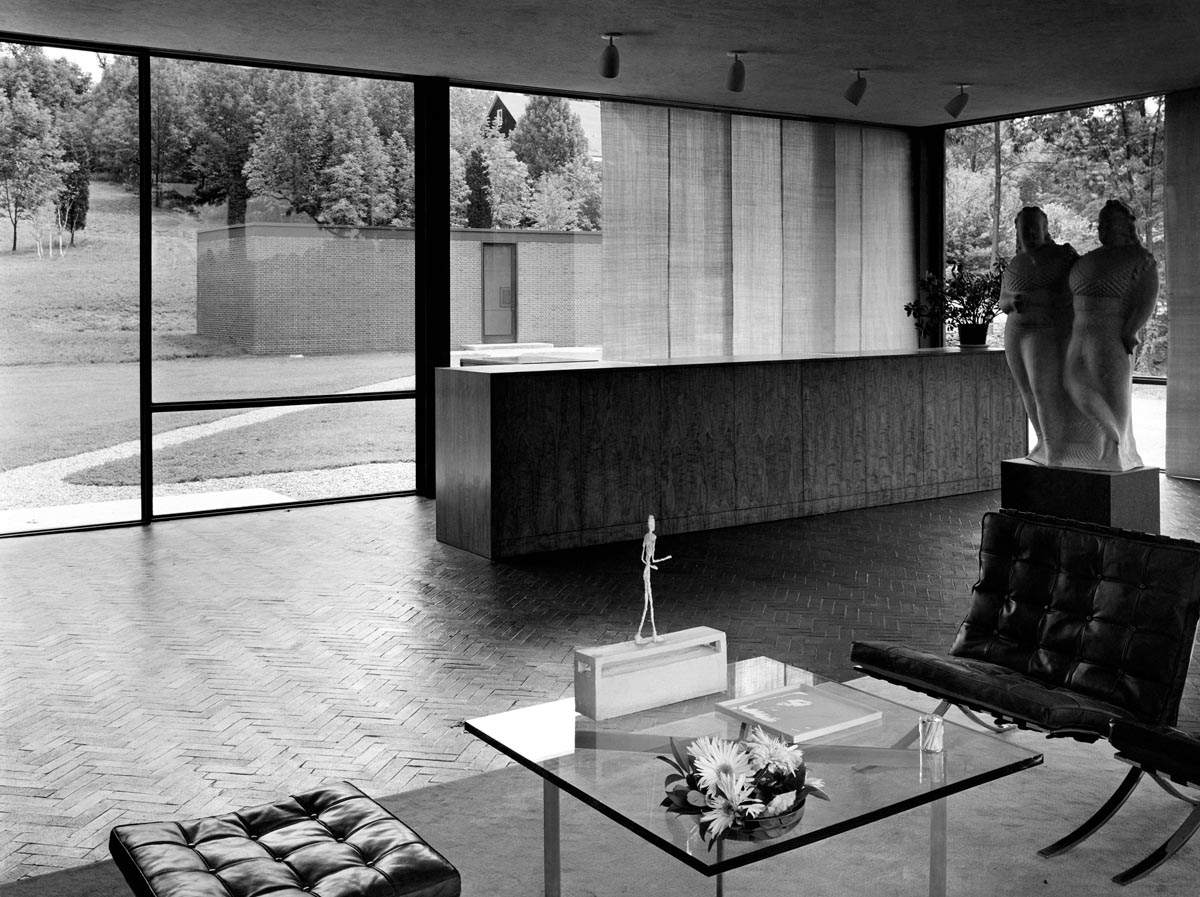

FIG. XVI The Glass House interior, as photographed in 1949. In part, it is a Johnsonian exercise in taste, with the MR furniture, the Nadelman twin figures, and the delicate Giacometti standing figure. (André Kertész/Condé Nast via Getty Images)

FIG. XVII Philip Johnson’s most essential work, the Glass House, in New Canaan, Connecticut, as recorded in 2006, one year after his death. (Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress/Prints and Photographs)

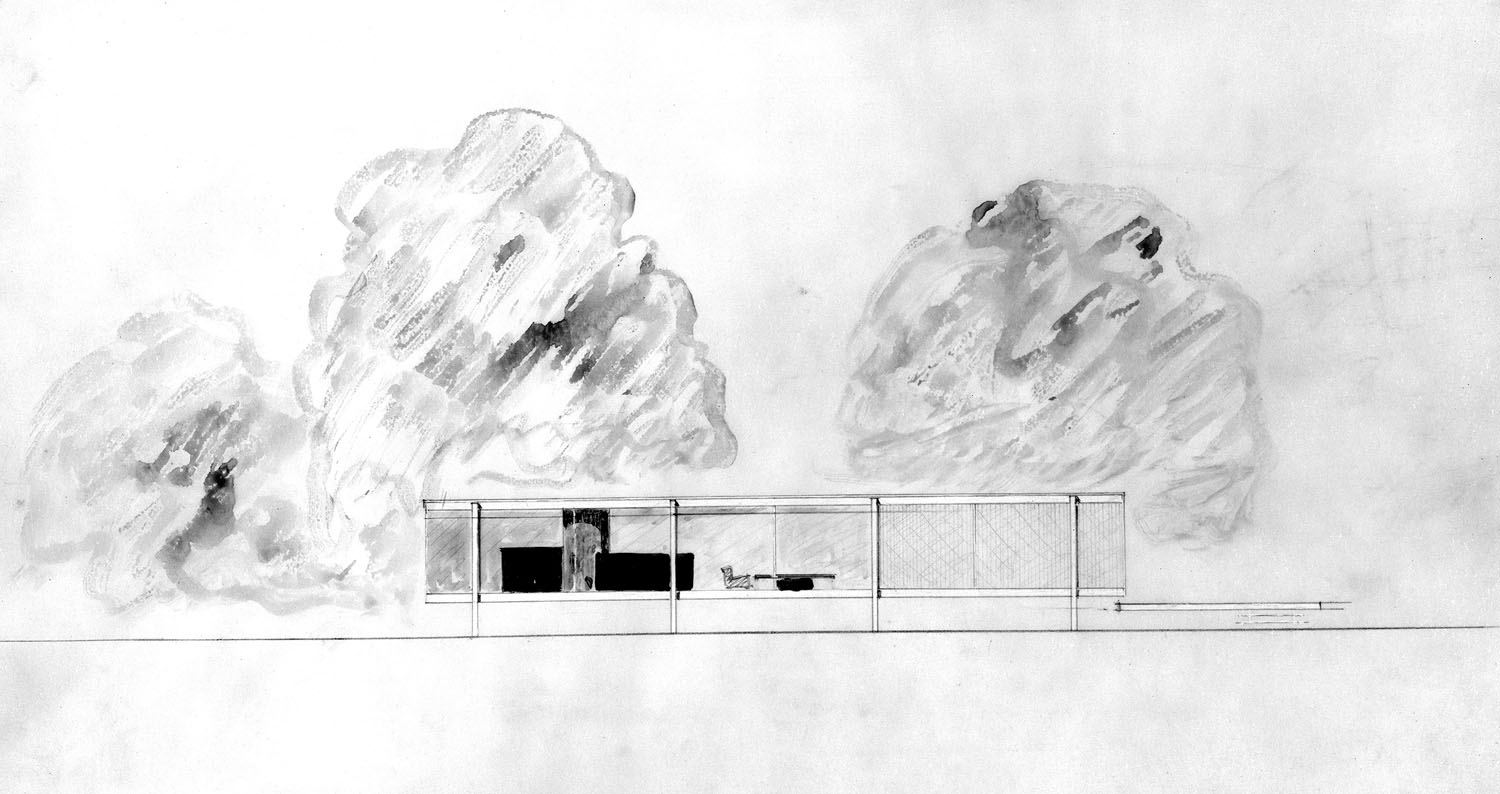

FIG. XVIII The first vision of the Farnsworth House, executed by Miës van der Rohe and delineator Edward Duckett. (Hedrich Blessing Collection/Chicago History Museum/Getty Images)

FIG. XIX Unlike Johnson’s earthbound house, Miës’s glass home for Edith Farnsworth stands atop piers, giving the illusion of floating above the grassy site near the Plano River. (Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress/Prints and Photographs)

FIG. XX A view of the “great workroom” at the Johnson Wax offices in Racine, Wisconsin, with its memorable, treelike support columns of poured concrete. (Jack Boucher, HABS, Library of Congress/Prints and Photographs)

FIG. XXI As photographed in 1958, the Seagram Building (left) framed by its modernist sister, Lever House, looking southeast. (Andreas Feininger/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

FIG. XXII Wright’s Romeo and Juliet Windmill, an eye-catcher visible far and wide from its hilltop overlooking the Helena Valley, Wisconsin. (Roger Straus III)

FIG. XXIII Johnson’s geometric exercise—a squared—off spiral stair to nowhere—in honor of his friend Lincoln Kirstein. (Photo by Grace Hough courtesy of the Glass House)

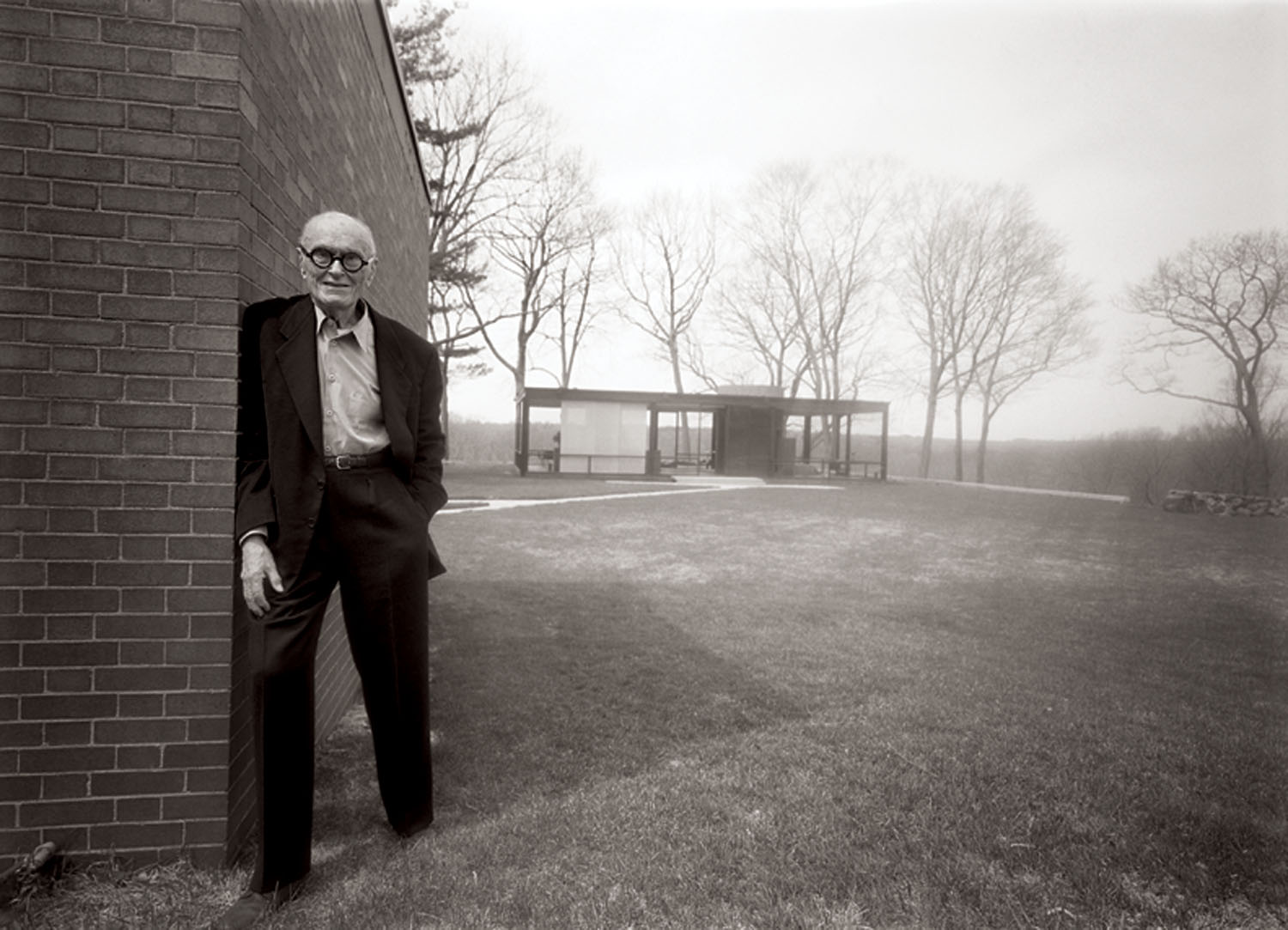

FIG. XXIV The aging Philip Johnson, still in residence after almost fifty years, leaning against the brick mass of the Guest House, with his more famous prismatic domicile behind him. (John Dolan)