TWENTY-THREE

Durban Vision; rosewood massacre

I’ve seen all the presidents of Madagascar since independence, though only met a couple of them. Presidents in Madagascar have far more power than in countries which pride themselves on checks and balances—presidents and their circle of henchpersons tell the country what to do.

Of course, many don’t listen. Villagers try to keep their heads down. Their experience of officialdom is foresters with power over land, petty clerks on the take, and literate people who ask them to sign incomprehensible papers which usually turn out to mean they have relinquished their rights. Among bureaucrats there is still a core of dedicated people who would very much like to run an honest and efficient civil service. Businessmen of course seek profit, but profit may be had either by weaseling round the system or by straightforward investments that yield jobs and growth as well as profit. But, still, it is the president who holds the financial reins, and whose policies set the country’s course internationally.

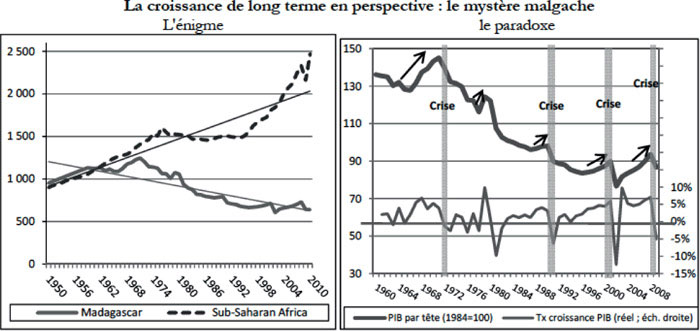

They have not done a very good job. Madagascar has declined in real per capita income ever since 1970. Mireille Razafindrakoto and her collaborators at the Institut de Recherches sur le Développement illustrate this starkly (overleaf). The left-hand graph shows the decline in per capita purchasing power compared to other African states. The right-hand graph shows the modest rises under each regime and the precipitous falls, with very slow recovery, at each regime change.1 As the economy grows, ‘so does the frustration of the excluded groups… Add to the mix a dash of weak institutions and a pinch of opportunistic disgruntled politicians, and you have all the ingredients of the ‘Madagascar Cycle.’2

Two questions. Why have the Malagasy put up with this for so long? And why has no president managed to change the trajectory?

Madagascar has a highly hierarchical society. Long before colonization the ruling Merina recognized some twenty-seven social castes, ranging from the highest nobility down to slaves at the bottom. French colonists moved in at the top, but without erasing the memories of who used to be whom. The Merina tribe also conquered many of the coastal tribes. ‘Ethnicity,’ or, to be frank, racial discrimination between more Indonesian plateau people and more African coastal people, is still strong. It matters how light or dark your skin is, how straight or kinky your hair. But underlying all these gradations is a kind of inertia or reticence or respect toward one’s superiors.

Malagasy have an especially strong tendency to accept those in power. They may see top politicians as ruling by right—to be raiamandreny—father-and-mother—a traditional term of respect for wisdom and semi-sacred power and fertility. This gives society an apparent peacefulness: a restraint which means that even when presidents have changed the country has not erupted into real civil war. It is true that violence can break through in mob lynching of a thief or mob looting of Indian shops. However, after the eruption, people regain an extraordinary surface of quiet etiquette toward each other. This is not just fear; it is tradition.3

The next question, why no regime has stopped the economic decline, is complicated. External pressures, from commodity price falls to imposed structural adjustment to the burden of debt, have not helped. But a part of the answer comes with Donald Stone’s remark, back in Ranomafana, that hope is a terrible risk for those in power. As conditions improve slightly, but never fast enough, people who have been left out take matters into their own hands and back some new politician who promises change.

Enter Marc Ravalomanana.

In early 2002, Marc Ravalomanana, the mayor of Antananarivo, won the presidential election. Didier Ratsiraka, who had been president for most of the years since 1975, did not accept the results. Six months of unrest followed, the ‘crisis’ with massive pro-Ravalomanana demonstrations in Tana, led by Lutheran exorcists to clear away the ‘devils.’ Demonstrations in the mornings, actually tidying up the Avenue de l’Indépendance by noon, after which people went to lunch and back to work. Meanwhile Ratsiraka’s militia dynamited the seven bridges to Tana, starving the capitol of petrol and other goods. Porters carried jerrycans of petrol across the river beds, for a price, sometimes smoking all the while. There was a real battle between army factions, in which 14 people were killed: 8 on one side, 5 on the other, and a woman who walked by at the wrong moment. There was no blood-bath, which one might expect in actual African countries. In the six months a total of some 100–150 people were killed, many to settle old scores or to loot their property. In the end, Ratsiraka summoned some old-time French mercenaries to help him. France had its eye on these veterans of other mercenary wars, so their plane was turned around halfway to Madagascar. President Ratsiraka promptly fled with family and friends.

Perhaps more people died of flu than of violence. At the same time as the ‘crisis,’ a strain of flu was killing villagers through much of the eastern forest. It was a banal strain: people in the west with a flu jab were already immunized. However, in a population severely malnourished, most of whom wouldn’t pay for medicine until at the point of death, it swept away the old, the very young, the infirm.

My colleague Hanta was in Tana during the ‘crisis.’ Her sons in their scout troops and aikido clubs volunteered to help patrol the capital. Richard and I did not arrive until Ravalomanana was firmly installed as president. The president was just about to fly to the UN, where he pledged to support the environment with an actual percentage of government revenue.

The extraordinary ex-ambassador Léon Rajaobelina put him up to it, in his post as director of Conservation International Madagascar. In this new capacity Léon could be an éminence grise both within and outside the country. It seemed that conservation was at last firmly on the national agenda.

Letter to family, Oct. 12, 2002.

Our 39th wedding anniversary!

This place is weird. There are now computers. There is even a phone book. Also even more child beggars on the streets, and grimy poverty: I think visibly worse than ever, though maybe I just know it is. Sample: the car slows in the endless traffic jam, and is surrounded by two different men selling car accessories: bumpy massage back-mats for drivers, a leopard-skin steering-wheel cover. They will never own a car or a steering wheel. Also two children: girl, maybe 7, and boy in an orange T-shirt with literally more holes than shirt, maybe 5. Bright-eyed, but of course they are stunted so are older than they look. Also a hand reaching up from below: a polio-crippled beggar on a rolling cart made of a plank on little wheels. The car lurches forward 10 feet and then we have the next lot of hopefuls.

The last time that I was in the Presidential Palace I was with a Canadian tourist, who was frogmarched into the guard-house for daring to snap photographs…

This time we were escorted in the front, between the curly iron gates, up to the ever-so-French-provincial facade of pink brick and white trim, three storeys of colonial pomposity. Set, indeed, in a lovely garden of purple-flowered jacaranda trees and a wide view of the hill town of Antananarivo. The anteroom where we waited was two storeys tall, arched French windows onto the garden, filmy white curtains and sunshine-yellow ones blowing in the breeze. We sat round a great polished table waiting our turn. The president’s schedule was a bit behind: a gang of portly oil men came in and sat down at the other end of the table to wait their turn after ours.

Ushered in: just one lackey. No obvious bodyguards. Marc Ravalomanana: a slight, erect, handsome man sitting at a long table in front of an inlay-on-black mural of plateau scenery, complete with women bending to plant rice, and oxen drawing carts. The president rose to greet us, shaking hands all round. Does he look less handsome than his pictures? A few more lines round the eyes. After all, he has taken the decisions for six months, first to call out the entire population in Gandhi-like resistance demonstrations, and then for the lightning-fast movement of troops to take over the towns whose governors still supported the old dictator. Also, he has just flown in from the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, where he made his maiden international speech as a head of state. Also, he’s leaving this afternoon for the General Assembly in New York. A few more wrinkles are understandable.

Richard, Gouri Ghosh and Eirah Gorre-Dale of Unicef made their pitch about hygiene and sanitation and the WASH4 campaign. He was polite, but not well briefed or enthusiastic. Maybe if they had a glitzier promise—to deal with the banal strain of flu that has claimed hundreds of lives of the very poor, or to deal with the economy set to deliver a minus 10 percent growth rate this year after the six months’ siege of the capital—then he’d have had more to say.

Maybe I got the happiest reaction. At the end, I said how much I admired his Johannesburg speech, especially its preamble that Madagascar is one of the countries with the greatest stake in the environment because practically all its wild fauna and flora are unique. I said that according to me and all my colleagues, Madagascar is one of the richest countries in the world.

‘I love fauna and flora, and we are indeed rich!’ he proclaimed, rising. ‘You see, even my office has orchids!’ It did: three pots with fronds of pink and white Madagascar orchids, each flower spray taller than a man. So we wound up taking his picture with his orchids, as well as with ourselves. And then we took our leave, while he went on with the affairs of state.

And the rather more substantial interview with the oil men…

A year later, in September 2003 at the World Parks Congress in Durban, Ravalomanana announced the ‘Durban Vision.’ Madagascar would triple the extent of its protected forest areas up to 6 million hectares. The new areas would be community owned, and more or less community managed. This reversed more than a century of colonial and pre-colonial fiat that all forest land belonged to the state.

A consortium of advisors implemented the ‘Durban Vision,’ led of course by Léon and Conservation International. Madagascar then designated 2 million hectares of new forest reserve areas in each of three successive years.

Of course, with all this haste, there were many cases of misallocation. Often the people who came to the consultations on the ground did not actually represent their local communities. Sometimes they did not include sacred forests in the scheme, thinking these were already protected since time immemorial, thus missing out the most important areas to benefit. Above all, although the forests were to be under community management, few at any level were clear quite what this would mean. Still, it was a huge lurch forward in the idea that people themselves would and could manage their own landscapes. Even a paper designation of a reserved forest goes some way toward its protection.5

Over the next years, Ravalomanana implemented many of his other election promises. Hundreds of new schools were built, teachers paid. Every child received a backpack with a new notebook, pencils and rulers, of which they were inordinately proud. Clinics opened. A free-trade zone in Antananarivo mushroomed into a thriving textile center. A nationwide election in 2006 confirmed Ravalomanana’s mandate as president (but the Malagasy nearly always re-elect a sitting president). To the fury of France, he announced that English should be taught in all schools, with the goal of Madagascar, like Mauritius, becoming a trilingual country able to operate in the Internet-connected world.

It wasn’t squeaky clean. The Ravalomanana enterprises prospered greatly, from computer imports to dairy products. But the self-made millionaire went on coining money from long-term, productive investments in the country, expecting that his businesses and his presidency were in it for the long haul.

Then Ravalomanana made a big mistake. He allowed foreigners to own land. A huge land grab in the west of some 1.3 million hectares was leased for ninety-nine years to the Daewoo company of Korea to grow maize and oil palm. Domestic and foreign press screamed about that one. It wasn’t mostly arable, because the small patches of arable land in Madagascar are bisected by grassy hill-pastures, but it was hard to believe that Daewoo’s promises of employment and investment would in any way compensate local people who had lost their farms and their grazing rights—let alone address the semi-sacred status of ancestral land. Still, that was in the far west. Ravalomanana, who had made his first fortune from his family’s yogurt business, was all for improving cattle and dairy yields. He very obviously paved over rice fields on the road from the capital to the airport for a factory to produce high-quality animal chow. That was an immediate and obvious insult: turning productive rice paddies into an animal food factory was visibly disgusting.

His even bigger mistake: he built schools and clinics, as he later wryly remarked, instead of raising army salaries. In March 2009 the mayor of Antananarivo, Andry Rajaoelina, staged a coup. Mobs in one night burned down several of the Ravalomanana factories and his party-run radio station. There was some loss of life—mainly among the rioters caught in the flames while looting the Ravalomanana-owned supermarket. A faction of the army supported Andry.

When I first saw Andry’s posters in his mayoral campaign, I thought they were advertising a pop star. Not so far wrong: 30-year-old Andry had been a disc jockey. Someone backed and bankrolled the young man, of course, but I am not repeating here the rumors naming obvious suspects—mostly French companies encouraged by a French government. Anyway, Andry wasn’t much younger than President Ratsiraka back in 1975.

Then Ravalomanana, or his adjutants, did just what Ratsiraka had done in 1991: they fired on a crowd. At a demonstration in front of the Presidential Palace some seventy protesters were killed. Among them was my friend Hanta’s eldest son on his first job as a journalist standing out in front of the crowd holding a microphone. Hanta, her husband Niry, and all of us who knew them were stunned with grief, as were so many other families.

Ravalomanana fled to South Africa.

The new government was flagrantly illegal. Foreign donors promptly froze all non-humanitarian aid. Much of government expenditure and all infrastructure improvement were wiped out: foreign aid and loans had been 40 percent of the government budget. Educational enrollments plummeted. Health clinics closed. Businesses in the free-trade zone packed up and moved to other countries.

The ‘transitional’ government plundered its honey-pot: the rosewood of the eastern forest reserves.

It is estimated that rosewood worth a quarter of a billion dollars left Madagascar for China in 2009 alone. And as much again in 2010. The quantities have tailed off since—to some extent. The shipments are and always have been illegal. The proceeds were obviously not much to Madagascar: Chinese importers are not so kind. Nor did much go to people who actually risked their lives felling giant trees on slippery slopes: their wages were under $2 a day. Even that, though, was a wage for an unemployed laborer, so there was no dearth of candidates for the jobs. The main proceeds, instead, were split between the timber barons of the east coast and the people at top levels of government who took their cut.

Rosewood is dense, beautiful hardwood. A cut rosewood trunk does not float. To slide a cut trunk to the nearest stream you have to hack a slipway out of the mountainside. Then you cut three to five other trees of lighter consistency. You tie them to the rosewood to raft it down the river. It is piled onto trucks at the landing stage—diesel dinosaurs like the one Eleanor Sterling and I rode to Ivontaka twenty-five years ago. It is stacked in warehouses, and then loaded onto ships with falsified manifests, and then conveniently overlooked by customs officers. When a cargo is spotted it is the low-level customs people who are fined and jailed, never the bosses.

This didn’t pass unnoticed. There are heroes of the struggle, like Erik Patel and his Malagasy colleagues. Erik was a graduate student from Cornell studying silky sifaka, his Ph.D. much delayed by the assault on his site and his animals. Silky sifaka are one of the world’s rarest primates, creatures with pink and black spotted faces and an aureole of long white fly-away fur. They live only in the national park of Marojejy: vertical mountain slopes clothed in dense rainforest that used to be full of rosewood trees. Erik, expats and brave Malagasy managed to get articles into the National Geographic, undercover films on the BBC, outrage in the journals of the world. The rosewood massacre has slowed, but not stopped. In the USA Gibson Guitars was sanctioned for using tiny slivers of Madagascar rosewood for fretboards. In my opinion, to use a few bits of rosewood to make fine sculpture or sonorous music should be applauded. Meanwhile no one has stopped the Chinese carving ‘Ming dynasty’ four-poster beds, each post a whole tree. I saw one bed advertised on the web at a million dollars.

January 19, 2010.

Léon Rajaobelina is off to Washington this week to testify in front of the subcommittee on Africa of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the House of Representatives on the impact of climate change on African countries. Also to lobby the US Congress to lift sanctions on the environment sphere. The rosewood massacre will continue unless the civil service is paid, including the Eaux et Forêts and the National Parks Service and some of the police.

Unicef is trying to step in for the community health centers—hence I joined the three-Land Rover mission to the south. A great deal of aid has been reclassified as humanitarian, via Unicef, but you can’t expect other people to provide all the essential services of a country, let alone guard its National Parks.

The international community can only have sanctions against the populace, not against Andry—because he is a French citizen!

It was inconceivable a year ago that Mad. would join the roster of failed states. It hasn’t happened yet, but it is now conceivable.

On the other hand, it has not failed yet as badly as some. Björn (on our Unicef mission) made a present to Bruno the Unicef rep of a crisp, new, small-sized banknote from Zimbabwe, value $10 trillion. He regrets having missed the largest version, for $100 trillion, which is as high as they went before switching entirely to US dollars.

But the real prize is revenue from minerals and oil. The rosewood massacre was a mere stopgap. Big mining revenue is still in the future—but arguably the ‘transition’ of Andry’s cronies was sparked by the rush under the previous Ravalomanana government to open concessions for minerals and oil.

Madagascar, which has suffered so much poverty, may now be set for the final insult: the Midas curse of wealth.

1. M. Razafindrakoto, F. Roubaud et al., Institution, gouvernance et croissance de long terme à Madagascar: l’enigme et le paradox (2013). This report offers an extensive analysis with interviews and statistics to explain why people accept the stagnation of the economy under successive regimes. Don’t worry about the graph axes: the first is in constant 1984 Malagasy francs, the second in purchasing power of constant 1990 (Geary-Khamis) dollars. The point is the direction of change.

2. S. Andriamananjara and A. Sy (2013). ‘It’s time to break the ‘Madagascar Cycle.’

3. C. Alexandre, Violences Malgaches (2007). An attempt by a French priest to understand Malagasy peacefulness and sporadic outbursts, as well as why circumlocutions in meetings baffle expatriates—so often the speaker is unwilling to commit himself until hearing others.

4. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene campaign, supported by Unicef, Water Aid and others.

5. C. Corson, ‘Territorialization, enclosure and non-state influence in struggles over Madagascar’s forests’ (2011); C. Corson, ‘From rhetoric to practice: how high-profile politics impeded community consultation in Madagascar’s new protected areas’ (2012).