Replica of the Golden Hind, under sail at sea. The Golden Hind was the only one of the three in Drake’s small fleet to survive the circumnavigation voyage. This replica ship was built in 1973 and has itself circumnavigated the world.

SIR FRANCIS DRAKE’S

CIRCUMNAVIGATION MEDAL

OBERON: We the globe can compass soon, Swifter than the wandering moon.

PUCK: I’ll put a girdle round about the earth In forty minutes.

On Christmas Eve 1968, Apollo 8 became the first manned spaceship to circle the moon, and the film footage that NASA sent back changed our perception of the world. For there, as the three astronauts rounded the dark side of the moon, was the earth itself, a great globe suspended in the vast darkness of space. It was the first time any human being had seen the whole planet at a single glance, and the world has thought about itself differently ever since.

Nearly four hundred years earlier, a very different journey had caused a comparable revolution if on a smaller, national scale. In 1580, Sir Francis Drake became the first Englishman, and only the second captain in history, to sail his ship round the globe. In consequence, to the English, the world looked suddenly different. Its limits were known: it could be mapped and plotted. It could be circled and crossed by a single English ship. In 1580, Shakespeare was sixteen. For him and his contemporaries, the boundaries of human possibility – for travel, adventure, knowledge and conflict – had been dramatically expanded.

Replica of the Golden Hind, under sail at sea. The Golden Hind was the only one of the three in Drake’s small fleet to survive the circumnavigation voyage. This replica ship was built in 1973 and has itself circumnavigated the world.

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the mischievous Puck boasts to Oberon, king of the fairies, that he can circumnavigate the globe in just over half an hour – even faster than a modern satellite, which at 200 miles up takes about ninety minutes. As everybody in the audience knew, it had taken Francis Drake nearly three years. The silver medal struck to celebrate Drake’s achievement shows the world that he traversed. It is about seven centimetres in diameter and almost paper-thin. On one side are Europe, Africa and Asia, and on the other the Americas. As you turn it in the light, you can see tiny dots indicating the route that Drake followed. From Plymouth down to the tip of South America, up the coast of South America, where Lima and Panama are both marked, on to California, over the Pacific to the Spice Islands in Indonesia, then round the Cape of Good Hope, up the coast of West Africa and home. An inscription around the South Pole tells us, in abbreviated Latin, ‘D. F. Dra. Exitus anno 1577 id. Dece.’ (‘The departure of Francis Drake, in the year 1577, on the ides [13th] of December’), and one on the other side records his ‘Reditus anno 1580. 4 Cal. Oc.’ (‘Return in the year 1580 on the 4th of the calends of October [28 September]’).

Created about the time that Shakespeare began his theatrical career in London, this silver souvenir map – glamorous, scientific, fashionable – lets us grasp, literally, how you could imagine the world in the 1580s and 1590s. For the Elizabethan play-goer watching A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the 1590s for the first time, encompassing the globe, putting a girdle around the earth, was news – patriotic news that every person in the audience would have known about. In their Athenian wood, Shakespeare’s very English fairies are, in their whimsical, poetical way, restating the nation’s pride in Drake’s accomplishment, just like this silver medal.

One of Drake’s crew described the end of the dramatic round-the-world journey on the Golden Hind:

And the 26 of September* we safely with joyful minds and thankful hearts to God arrived at Plimouth, the place of our setting forth after we had spent 2 yeares 10 moneths and some odd few days besides in seeing the wonders of the Lord in the deep, in discouering so many admirable things, in going through so many strange adventures, in escaping out of so many dangers, and ouercoming so many difficulties in this our encompassing of the neather globe, and passing round the world.

This ‘passing round the world’ brought with it exotic goods and even more exotic tales that would go on to fire the public imagination. Just as importantly, it was the sixteenth-century equivalent of the ‘space race’, as England, with far fewer resources, first tried to match Spain’s skill and technology in navigating and then began to raid the huge wealth of the Spanish Empire. This circumnavigation medal celebrates England’s first great success on both fronts, and the next two decades saw dozens of English adventurers set off to emulate Drake’s example. England’s passion for seafaring became a heady confluence of plundering and exploration, scientific inquiry and geopolitical manoeuvring.

During his journey, Drake discovered two important facts till then unknown to Europeans. He ‘found’ the new lands north of present-day California, but, of more immediate strategic significance, he showed that Tierra del Fuego was part of an archipelago, and not connected to the supposed southern continent, the Terra Australis. This meant he had found a new route, later to be named Drake’s Passage, from the South Atlantic to the Pacific, which did not involve passing through the Spanish-controlled Strait of Magellan. For strategic reasons, the precise details of Drake’s voyage, in particular his discovery of the true extent of Tierra del Fuego, were treated as a state secret for several years. It was only after the English saw off the Spanish Armada in 1588 that a large map of the circumnavigation went on triumphant public display on the walls of Elizabeth I’s palace in Whitehall. The palace was a public place, where much business was done, open to thousands of visitors – and Shakespeare would almost certainly have been amongst them. Our silver medal was a reduced, portable version of the Whitehall wall map with exactly the same purpose – to be a patriotic statement of Drake’s great feat. The medal, like the map, was a calculated piece of political propaganda.

Peter Barber, responsible for the maps at the British Library, is intrigued by the way the Drake map/medal presents its ‘information’:

If you look, you’ll see that at the top of North America, there is a little note saying that this was discovered by the English (which historically speaking is fairly outrageous) and further down you have a marking of the Virginia colony, which would have made any Spaniard see red. But what is particularly interesting is that the Virginia colony, which is marked on the medal, was founded after Drake got back from his round the world cruise. So this map we now know was not made in 1580, but 1589, in other words a year after the Armada.

The provocative teasing of the Spaniards goes on all over this very cheeky medal. Just above California you can see in large letters the words ‘Nova Albion’ (New England or New Britain) striding across much of North America. Below, ‘N. Hispania’ (New Spain) looks as though it could be just a cattle ranch west of Texas.

Somewhere off the coast of Peru and Panama, Drake had raided Spanish ships and had captured nearly ten tons of silver, and to add insult to Spanish injury the medal is almost certainly made from that stolen silver. The silver also bought spices in the East Indies (the Spice Islands are named in surprising detail) so Drake came home to Plymouth with a cargo worth a fortune, having turned a serious profit on his expedition. His financial backers recovered their investment many times over, while the Queen took a share that almost doubled her annual income. An exploration of this kind was not just an adventure, it was also big business, and maps and globes allowed everybody, not just the investors, to share in the fun. Maps had of course been in circulation for a long time. Globes were rarer, but much sought after, and by the 1590s were being produced in London – two magnificent examples made by Emery Molyneux can still be seen in Middle Temple.

Terrestrial globe from a set in Middle Temple Library, London. The very first English-made globes were produced by Emery Molyneux in 1592; Shakespeare seems to refer to them in The Comedy of Errors, produced around the same year.

In The Comedy of Errors, written around 1592, Dromio, the quick-witted servant, outrageously compares a plump kitchen maid to a globe as he sets off on a raunchy geography lesson, looking for treasure all over her.

DROMIO: She is spherical, like a globe. I could find out countries in her.

ANTIPHOLUS: In what part of her body stands Ireland?

DROMIO: Marry, in her buttocks. I found it out by the bogs.

ANTIPHOLUS: Where Scotland?

DROMIO: I found it by the barrenness, hard in the palm of her hand.

The wretched maid is the butt of one sexist, xenophobic joke after another.

ANTIPHOLUS: Where America, the Indies?

DROMIO: Oh, sir, upon her nose all o’er embellished with rubies, carbuncles, sapphires, declining their rich aspect to the hot breath of Spain; who sent whole armadoes of carracks to be ballast at her nose.

ANTIPHOLUS: Where stood Belgia, the Netherlands?

DROMIO: Oh, sir, I did not look so low.

Eventually the kitchen maid, like the globe, is completely circumnavigated. Like the maid, like Spanish silver, the world is there for the taking. The Drake silver medal is merely the top end of a huge market for maps that let the English of all classes see where their ships had been venturing.

Jonathan Bate, Shakespeare scholar and biographer, describes this development:

It is not really until the period when Shakespeare’s plays are being written, the end of Queen Elizabeth’s reign, that people get a real visual sense of the whole world, and in particular the roundness of the world. There is a lovely moment in Twelfth Night where Malvolio is being forced to smile and the smile is causing lines to crease his face, and Maria says ‘he does smile his face into more lines than is in the new map with the augmentation of the Indies’. She is referring there to a very famous map that was made in 1599 to accompany Hakluyt’s Principall Navigations, a book that gave an account of the voyages of the English navigators around the world, and in that map there are lines of latitude and longitude, so it looks like a sort of creased face. But that map of the augmentation of the Indies [that is, with the very latest geographical information added] was clearly a great novelty at the time.

Richard Hakluyt’s famous and widely read book The Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation had first appeared in 1589, but a significant new edition, updated and expanded into three volumes, was published ten years later. It was a work that both commemorated the triumph of English seafaring and urged further exploration and swifter colonization. The 1590s saw Sir Walter Raleigh’s exploration of Guiana and Venezuela and in 1596, the year after his return, publication of his book, The Discovery of Guiana. Its heated claims of adventure and untold riches caught the public imagination, and in Merry Wives of Windsor Falstaff compares one of the two women he hopes to conquer to the great golden city described by Raleigh:

FALSTAFF: Here’s another letter to her. She bears the purse too. She is a region in Guiana, all gold and bounty. I will be cheaters to them both, and they shall be exchequers to me. They shall be my East and West Indies, and I will trade to them both.

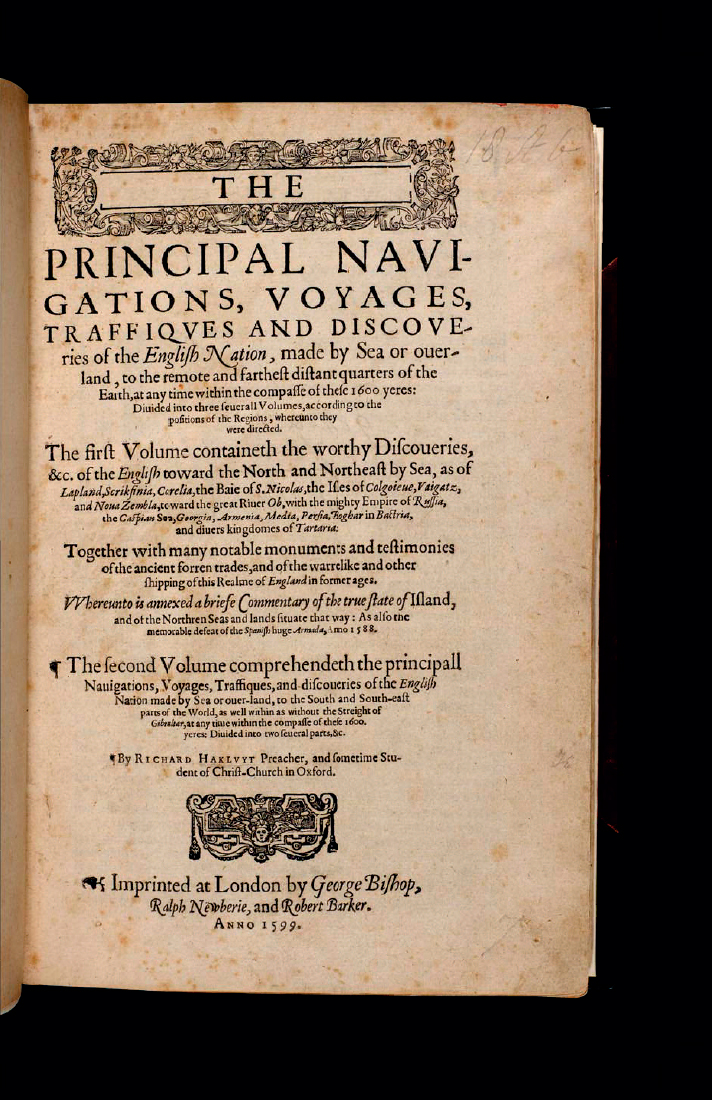

Title page of Richard Hakluyt’s The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation, which included the first account in print of Drake’s voyage written by a participant.

PREVIOUS PAGES: World map from the second edition of Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations (1599). Shakespeare’s reference in Twelfth Night to ‘the new map with the augmentation of the Indies’ is probably to this map.

Most of Shakespeare’s plays that bring in exploration and discovery in this way cluster in the 1590s, the high days of Elizabethan seafaring.

The maps in Hakluyt, like this medal and indeed all maps and globes in Elizabethan England, were not of course navigational tools to be used to find your way around, but evidence of journeys taken by others. Peter Barber again:

The first place an Elizabethan would have most likely have found a map would have been in a Bible. Protestant Bibles particularly contained maps to prove the veracity of the scriptures. This is where you went to see where important things happened, and to prove that they actually happened there. As English sailors told the authorities repeatedly in the 16th century, maps were a fat lot of use when you were actually at sea. So the sort of maps we are looking at in the context of Shakespeare are really for armchair travelling, and they are interesting for their symbolic and educational aspects. In 1570 the first book of entirely modern maps was published, called The Theatre of the Lands of the World. So this idea of the world as a stage, which was picked up by Shakespeare, was around long before him.

The Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (The Theatre of the Lands of the World) was the first atlas as we would recognize it. The year before, in 1569, his compatriot Gerard Mercator had produced a ‘new and augmented description of Earth corrected for the use of sailors’, as he called it, based on what we now know as the Mercator projection. Mercator’s mathematical calculations allowed for the planetary sphere to be expressed as a two-dimensional image and became the basis for the map of the world most familiar to us today. Gerard Mercator also sired a great dynasty of cartographers; one of the nine surviving Drake Circumnavigation medals is actually inscribed in abbreviated Latin: ‘Micha. Merca: fecit extat Londi: prope templum Gallo: An 1589’ (‘Michael Mercator made this. It is available in London near the French Church, 1589’). Perhaps Michael, Gerard Mercator’s grandson, produced a prototype Circumnavigation medal for Drake, who then commissioned more for distribution among friends and followers. When it was reproduced, Mercator’s name was omitted, probably to allow Drake’s name greater prominence. The connection with the Mercator family continues further, because the outline on the medal is based on the double-hemisphere world map drawn by Rumold Mercator, one of Gerard’s sons, published in the first volume of Gerard Mercator’s great Atlas of 1589.

Francis Drake, unknown artist, c.1580. Drake’s circumnavigation voyage and successes against Spain made him an international celebrity. He is depicted here with his hand on a globe to highlight his great feat.

*

The reconstructed Globe Theatre on London’s South Bank opened in 1997 and has proved a huge asset in understanding the theatre of Shakespeare’s day.

The theatre which is most associated with Shakespeare today is a great London tourist attraction on the south bank of the Thames. But when Shakespeare and the equivalent of his marketing department sat down at the end of the 1590s to name it, they must have wanted a name that would fire the public imagination and outdo all the existing theatres – the Curtain, the Rose, and the one called, with a startling lack of originality, simply The Theatre. Shakespeare’s company by contrast chose a name that was topical, one that, like that book of maps, was the Theatre of the Lands of the World, outlining all human experience. The name they chose was the Globe – a new way of thinking and showing the world.

Imagine you are a young Londoner in the mid 1590s. You have been on business at Whitehall palace, where you have seen the great wall map of Drake’s voyage, and then you decide to go to that Shakespeare play you have heard about, A Midsummer Night’s Dream. When you come to the scene between Oberon and Puck, just how much more resonant will these words be to you than to your jaded and globalized descendants some four hundred years later?

OBERON: We the globe can compass soon, Swifter than the wandering moon.

PUCK: I’ll put a girdle round about the earth In forty minutes.