RAPIER AND DAGGER FROM THE THAMES FORESHORE

The streets of London were a dangerous place in the sixteenth century. In Shakespeare’s day you could calmly admire a swordfight on stage and then find yourself perilously embroiled in one when you stepped beyond the theatre walls. In London, just as in Verona, an evening out could end up a very bloody business:

ROMEO: Gentle Mercutio, put thy rapier up.

MERCUTIO: Come, sir, your passado!

[They fight]

ROMEO: Draw, Benvolio. Beat down their weapons.

Gentlemen, for shame! Forbear this outrage!

Tybalt, Mercutio, the Prince expressly hath

Forbid this bandying in Verona streets.

Hold, Tybalt! Good Mercutio!

[Tybalt under Romeo’s arm thrusts Mercutio]

MERCUTIO: I am hurt.

A plague a’ both houses! I am sped.

Romeo and Benvolio try their best to stop the swordfight between their friend Mercutio and the hotshot swordsman, Tybalt, but it is hopeless. Mercutio is stabbed, and once again the streets of Verona run with blood.

We tend to think of Romeo and Juliet as essentially the balcony scene, a play about the romantic tribulations of young love. In fact it is just as much a play about bands of privileged lads slicing each other to death and the failure of the authorities to control their brawling. Romeo and Juliet, with its upmarket knife gangs and its bloodstained streets, leaves no doubt that urban violence – for Shakespeare and his audience – was one of the big issues of the day.

The weapons of choice were generally a dagger and a rapier, as in these examples, now housed at the Royal Armouries in Leeds. The dagger was made around 1600 and is bigger than you might expect, roughly the size of a modern carving knife – the dagger that hovered before Macbeth was clearly no slight weapon. Its companion piece, the rapier, is not equipment for the battlefield: the slender blade was designed to pierce clothing, not armour. This was the sort of weapon you carried around with you on the streets of Elizabethan England. Part dress accessories, part weapons, a rapier and dagger were essential kit for any young man out on the town.

In Shakespeare’s day there were only two ways of getting from the City of London to the south bank. Either you walked over London Bridge or you took a rowing boat or ferry over the river. Our dagger was found on the foreshore of the Thames, on the south bank: probably dropped by a young man as he got in or out of one of those rowing boats. We do not know, of course, whether the young man who lost his dagger was out looking for trouble as he set foot in Southwark. Nor, of course, do we know what clothes he was wearing, but he was almost certainly dressed in his best gear and looking for fun, because one of the main reasons for a young man to go south of the river was to get to the roaring entertainments on Bankside, which we first encountered in Chapter Three.

There were the theatres, of course – the Rose, the Swan, the Globe. But there were also bear-pits and cock-pits, brothels and inns – all easily accessible, and all conveniently outside the authority of the City of London. There were at least five bear-baiting establishments in the area around the Rose and the Globe, and some bears became national celebrities – the famous bear Sackerson was given a cameo role in The Merry Wives of Windsor:

SLENDER: That’s meat and drink to me, now. I have seen Sackerson loose twenty times, and have taken him by the chain. But, I warrant you, the women have so cried and shrieked at it that it passed. But women, indeed, cannot abide ’em – they are very ill-favoured rough things.

The south bank, with its wild entertainments, reckless youths and impresarios determined to make fast money, could be a dangerous place; particularly when groups of Elizabethan lads – not so different from the characters in Romeo and Juliet – carried lethal weapons with them. Toby Capwell, curator of arms at the Wallace Collection, says:

Once they become part of your dress as a gentleman, there is always the temptation to use them. If everybody is going to carry swords around all the time, they are going to come out pretty quickly in the event of an argument.

To be fashionable in the sixteenth century you needed to carry a sword. Only a gentleman was entitled to do so, and a true gentleman was expected to, as we know Shakespeare himself did. So it should be no surprise that the earliest known use of the word ‘blade’ to refer to a stylish young man appears in Romeo and Juliet. If the scenes between those young blades Tybalt and Mercutio are still vivid today, it is because such fights were not some fanciful invention, but the rough stuff of daily life.

The essential accompaniment to the dagger was the rapier, and this fine one was also found on the Thames foreshore – perhaps another casualty of a young man’s night on the town in Southwark, dropped as its drunken owner stumbled back into the rowing boat to take him home. This is an impressive weapon. The blade alone is well over a metre long, and it is sharp on both sides and at the end – you can slash, you can pierce with this rapier, while the matching dagger would be held in the left hand, parrying and stabbing at close range.

Going to Bankside, from Michael van Meer’s friendship album, c.1619. The Thames was covered with watermen ferrying customers across and along the river. The watermen were active supporters of the Southwark theatres, whose popularity added greatly to their income.

It is clearly an expensive, elegant weapon, and the owner must have been sorry to lose it. It has been elaborately worked – at the handle, it looks as though a long, thin metal snake has coiled itself around the base of the blade to protect the owner’s hand while he is fighting. A weapon like this would have been worn in what Elizabethans called a hanger, or girdle – a sort of sling. This would have made it easier to carry, because it was certainly not light in the hand. Toby Capwell again:

We always think of rapiers as a kind of feather-light flashing blade, the weapon of Errol Flynn and Douglas Fairbanks, and of medieval swords, conversely, as being heavy and cumbersome.

But actually this is a misconception: medieval swords tend to be very light, while real rapiers tend to be quite heavy and can seem, to an untutored hand, quite ungainly.

Yet when rapiers and daggers found themselves in tutored hands, the result was, in the words of Mercutio, a kind of musical performance, an exquisite dance of death:

MERCUTIO: He fights as you sing prick-song: keeps time, distance, and proportion. He rests his minim rests, one, two, and the third in your bosom. The very butcher of a silk button. A duellist, a duellist. A gentleman of the very first house, of the first and second cause. Ah, the immortal passado! the punto reverso! the hay!

Mercutio’s description of Tybalt’s skills with a rapier and dagger captures a fashion in swordsmanship that was new in England. As Alison de Burgh, fight master at the National Theatre, explains, Tybalt’s fighting was not just deadly, it was also the last word in foreign chic:

Shakespeare was picking up on the contemporary conflict between the English school of swordplay and the new Italian school of rapier play. Romeo’s family are fighting in the old English style of swordplay, Tybalt’s are fighting in the new Italian style; a fact made evident by the terminology Mercutio uses when he makes fun of Tybalt and Tybalt’s style of swordplay. Mercutio talks of the passado, the punto reverso, and makes up a move called the hay. Through Mercutio using these words and making fun of the moves, Shakespeare is echoing a gentleman who wrote a manual on English swordplay in which he criticized the Italian school. A famous Italian Master, Vincentio Saviolo, had recently established a school and written a manual on his style of swordplay. The Englishman George Silver wrote a manual on swordplay in which he advocates the English style and denigrates the Italian style. Mercutio is using words and phrases Silver uses in his manual.

Study of a gentleman carrying sword and daggers, by Jan van de Velde II, 1608–42. A rapier and dagger was an essential accessory for any early modern gentleman. Here the outline of weaponry is clear, despite the cloak drawn decorously around the body.

So the Montagues are good, true, solid Englishmen in their sword-fighting, while the Capulets – as the audience would have understood – are shown as suspect, modish and foreign.

For the man of fashion, the quality of his rapier and dagger set, like his watch or his trainers today, was crucial. In Hamlet, when the prissy courtier Osric announces a bet between the King and Laertes, the blades he mentions are as much status symbols as weapons:

OSRIC: The King, sir, hath wagered with him six Barbary horses, against the which he has impawned, as I take it, six French rapiers and poniards, with their assigns, as girdle, hangers, and so. Three of the carriages, in faith, are very dear to fancy, very responsive to the hilts, most delicate carriages, and of very liberal conceit.

Betting half a dozen rapiers and daggers against six Barbary horses shows just how enormously valuable a ‘delicate’ rapier and dagger could be.

But it was not just a question of fashion. Rapiers and daggers were about causing serious bodily harm: they proclaimed honour and defended it. The problem of street violence in sixteenth-century Europe was met with regulations to restrict the use of swords:

ROMEO: Tybalt, Mercutio, the prince expressly hath Forbid this bandying in Verona streets.

Some military experts despised fencing as a waste of time, ‘that men might butcher one another here at home in peace’, and poor preparation for the serious business of war. Others, such as the clergyman William Harrison, felt the rapier and dagger needlessly raised the stakes in civilian violence among fight-happy men who ‘carry two daggers or two rapiers in a sheath always about them, wherewith in every drunken fray they are known to work much mischief’. In an attempt to curb such violent brawls, an English law of 1562 limited the length of rapiers: those over a yard long were physically broken at the city gates. It seems to have made little difference: it was rather like saying you could carry only a small gun. Other laws were no more successful. According to a 1573 proclamation:

None shall wear spurs, swords, rapiers, daggers, skeans, wood knives, or hangers, buckles or girdles, gilt, silvered or damasked…except knights and baron’s sons, and others of higher degree and place.

Illustration from George Silver’s Paradoxes of Defence, 1599. Silver championed the English school of fencing against Saviolo’s Italian model – though both techniques involved using rapier and dagger together.

But such prohibitions were widely disregarded, and virtually every adult male carried at least a dagger.

Rather like boxing matches today, the sword fights that Elizabethans saw in the theatre were a hugely popular spectacle, and, barring the odd special-effect creation (like the arrows in Clifford’s neck in Henry VI, Part 3), the actors used real weapons. In daylight, in the open air, swordplay showed to particular advantage in the new playhouses like the Globe. Some actors became excellent fencers; the great comic actor Richard Tarleton, who could famously get an Elizabethan audience into hysterics simply by poking his face into view, also became a Master of Fencing, which meant he had defeated seven recognized masters in contests. There are over a dozen Shakespeare plays where swords are specifically required in the stage directions or in the action – among them are the great duels between Hal and Hotspur in Henry IV, Part 1, between Hamlet and Laertes, the battles in Henry V and the fight scenes of Romeo and Juliet. Comedy duels, as seen in Twelfth Night between Sir Andrew Aguecheek and Sebastian, were also hit scenes. Watching a proper fight, like the one between Hamlet and Laertes, was a two-for-the-price-of-one bargain: you got not only Shakespeare’s new play, but an excellent swordfight that the audience would willingly have paid to see on its own; indeed, when theatres were not staging plays they often offered fencing displays instead.

‘The Thyrde Dayes Discourse, of Rapier and Dagger’, from Vincentio Saviolo his Practise, 1595. The Italian fencing master Saviolo came to London in 1590, opened a school and published a manual in English. His techniques and terminology are quoted in Romeo and Juliet.

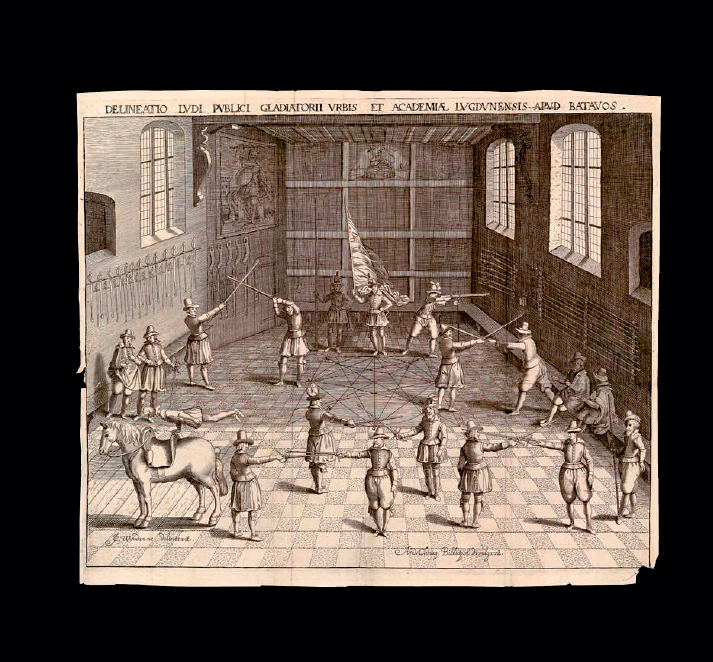

The fencing school of the University of Leiden, by Willem van Swanenburg, 1610. This Dutch engraving gives a sense of what the various fencing academies of Shakespeare’s London, including those of Saviolo and Silver, would have been like.

Among those watching Hamlet must have been many young men carrying rapiers and daggers like those they saw on stage. Unsurprisingly, they mirrored in real life what they saw in the theatre: in 1600 it was reported that gentlemen about town were fashionably copying the famous actor Burbage’s performance as Richard III, ‘That had his hand continuall on his dagger.’ Indeed, some members of the audience even fought duels as a result of incidents at the theatre, as when a young Irish lord blocked the view of the Countess of Essex at the Blackfriars Theatre and precipitated a duel with her escort.

Inevitably, actors and playwrights joined in the action off stage. Most famously, in 1593, a knife thrust in a Deptford tavern killed Shakespeare’s friend Christopher Marlowe, but there were several other theatrical casualties of the age. Gabriel Spencer, a rising actor in the Admiral’s Men, killed a man in a fight in 1596, and two years later he was himself killed in a duel by the playwright Ben Jonson, another good friend of Shakespeare. Philip Henslowe, the theatrical impresario, reported the event to the actor Edward Alleyn:

Now to let you understand the news, I will tell you some, but it is for me hard and heavy; since you were with me I have lost one of my company, that is Gabriel, for he is slain in Hoxton Fields by the hand of Benjamin Jonson; therefore I would fain have a little of your counsel if I could.

Jonson was indicted for murder but pleaded benefit of clergy; as a pardoned offender, he was branded on the thumb with T for Tyburn.

When it came to sword fighting, life imitated art and art imitated life. So it is perhaps not surprising that in 1596 a man called William Wayte claimed to have been set upon by four assailants outside the Swan Theatre and swore before the Court of Queen’s Bench that he had been in ‘fear of death’. Among the accused was the author of Romeo and Juliet, one William Shakespeare.