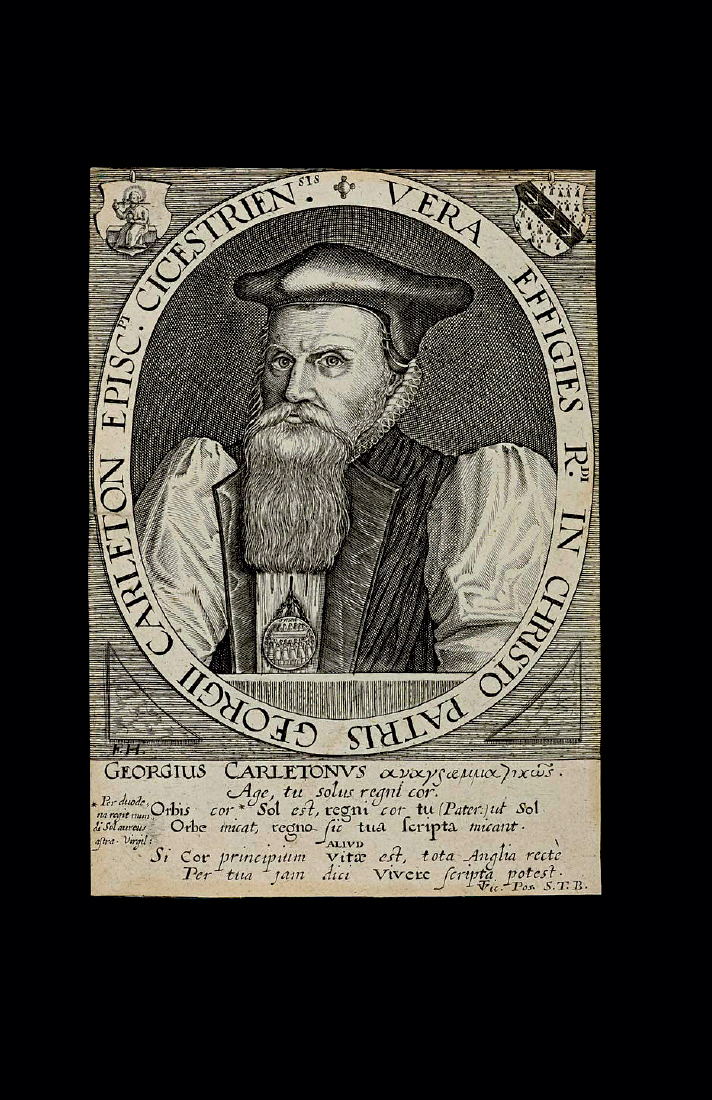

George Carleton, Bishop of Chichester, by Friedrich von Hulsen, 1627.

A MANUAL FOR MURDER

From the beginning to the end of Shakespeare’s career, the murder of the monarch is both the supreme crime and an abiding political conundrum. Richard II is killed on stage. By stabbing and drowning his own brother Clarence, and then smothering the young king and his brother in the tower, hunchbacked Richard of Gloucester becomes Richard III. And in The Tempest, Prospero, Duke of Milan, ends up on his island because his usurping brother has plotted to drown both him and his daughter Miranda (see Chapter Nine). Royal murder is at once catastrophe and commonplace. Shakespeare’s great lyrical improviser on this theme is Richard II:

KING RICHARD: For God’s sake let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings –

How some have been deposed, some slain in war,

Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed,

Some poisoned by their wives, some sleeping killed,

All murdered. For within the hollow crown

That rounds the mortal temples of a king

Keeps death his court; and there the antic sits,

Scoffing his state and grinning at his pomp,

Allowing him a breath, a little scene,

To monarchize, be feared, and kill with looks,

Infusing him with self and vain conceit,

As if this flesh which walls about our life

Were brass impregnable; and humoured thus,

Comes at the last, and with a little pin

Bores through his castle wall, and – farewell, king!

No one can come away from a Shakespeare play thinking life at the top is easy.

Rulers are always at risk. In our democratic age they may simply be ousted by votes. But through much of history and in much of the world, people who want to change rulers kill them. The death of a ruler is never just a personal tragedy: as it is a matter of national security, the whole state is affected. In Shakespeare’s Richard II, the Bishop of Carlisle spells out very clearly what will happen to England if the usurper Bolingbroke succeeds (as he does) in driving God’s chosen monarch, King Richard, off the throne:

BISHOP OF CARLISLE: let me prophesy

The blood of English shall manure the ground,

And future ages groan for this foul act.

Peace shall go sleep with Turks and infidels,

And in this seat of peace tumultuous wars

Shall kin with kin, and kind with kind, confound.

Disorder, horror, fear, and mutiny

Shall here inhabit, and this land be called

The field of Golgotha and dead men’s skulls.

O, if you raise this house against this house

It will the woefullest division prove

That ever fell upon this cursèd earth.

Prevent it; resist it; let it not be so,

Lest child, child’s children, cry against you woe.

In the world beyond the theatre, the subjects of Elizabeth I were also eloquently, and frequently, reminded of the dangers of political violence by regular reports of the crown in peril and the state in danger. Throughout Elizabeth’s reign, conspiracy followed conspiracy, with the Ridolfi plot of 1570 (see Chapter 4), the Throckmorton plot of 1583, the Babington plot of 1586 and the Lopez plot of 1594. In an era before modern media, news of these conspiracies was murkier, harder to be sure of, and so all the more potent. It circulated through pamphlets and woodcuts, broadside ballads and sermons, pedlars’ tales and, of course, rumour.

Shakespeare does not mention any of the plots that his audience must sometimes have discussed on their way to the theatre, but a contemporary of his, born a few years before him, wrote an entire book about them. He was another prophesying bishop, keen to remind his readers just how close England was to ‘disorder, horror, fear and mutiny’ and to becoming that field of ‘dead men’s skulls’. His book captures the mindset of the governing class during the decades in which Shakespeare was writing – suspicious to the point of paranoia, and always ready to retaliate with savagery.

The book was compiled by George Carleton, Bishop of Chichester, and was first published in 1624, a few years after Shakespeare’s death. The title page shows an ample female figure holding a large cloth on which is written ‘A Thankfull Remembrance of God’s Mercie by G. C.…’ It goes on: ‘An Historicall Collection of the great and merciful Deliverances of the Church and State of ENGLAND, since the Gospel beganne here to flourish, from the beginning of Queene Elizabeth.’ The title says it all, and Carleton’s best-selling book does indeed deliver exactly what it promises on the cover. In eighteen chapters he frightens and thrills his readers with fifty years of conspiracies, intrigues and assassination attempts.

The book is a tabloid history of England during Shakespeare’s lifetime, told entirely through plots to murder the monarch. Take for example, the Lopez conspiracy of 1594, which he presents as ‘a most dangerous and desperate treason. The point of conspiracy was Her Maties death…. The manner was poison.’

Title page of Carleton’s A Thankfvll Remembrance of Gods Mercie by G.C., London, 1627: a personification of the True Church holds up a banner displaying the book’s title, flanked by Elizabeth I and James I holding shields with their emblems and mottoes.

Throughout his book, the adversaries that Carleton describes are, as well as being mainly Catholic, also mainly foreign. They are the agents of the Kings of France and Spain and they are, more particularly, agents of the pope: ‘But he was drunke with the cup of Rome; for who would run such courses but drunken men? It may teach others to beware of those, that bring such poisoned and intoxicating cups from Rome.’ On and on, in high fulmination, Carleton goes, telling one rattling good yarn after another about evil Catholics and their dastardly acts. Time after time wicked people, aided by even more wicked and Catholic foreigners, set out to assassinate the monarch. Time after time they are foiled by loyal Englishmen and the grace of God. This is not about the divine right of kings, but the divine protection given to the Protestant rulers of England: Carleton seeks to show that without question God has been on ‘our’ – English, Protestant – side. Ultimately, the message of the book is triumphant, because all these plots against the King and Queen of England failed. Carleton’s stories are like a horror movie, danger watched (and tremulously enjoyed) from a place of safety. Strangers are concealed and in disguise. Foreigners lurk in the alleyway. As the tension mounts, the danger could not be greater.

Although none of these real plots features in Shakespeare, both the fact and the fear of conspiracy inhabit his work. Before he can set off for battle, Henry V has to deal with a group of noblemen found to be secretly in league with the King of France. Brutus and Cassius conspiring against Julius Caesar are, for Shakespeare’s audience, secret plotters of the sort they have been warned about, and, even more shocking, they are successful assassins. Julius Caesar is in many ways the archetypal assassination play, and in it Mark Antony describes the pain felt by the whole body politic when the ruler is murdered:

Woodcut from chapter 13 of Carleton’s A Thankfull Remembrance: ‘Lopez compounding [agreeing] to poyson the Queene’.

ANTONY: O, what a fall was there, my countrymen!

Then I, and you, and all of us fell down,

Whilst bloody treason flourished over us.

O, now you weep, and I perceive you feel

The dint of pity. These are gracious drops.

Kind souls, what weep you when you but behold

Our Caesar’s vesture wounded? Look you here,

Here is himself, marred, as you see, with traitors.

Shakespeare’s audiences could have told their own sad stories of the death of kings. Across Europe rulers fell before the dagger, the bullet, the cup of poison. Erik XIV of Sweden, enthusiastic suitor of Elizabeth, was poisoned in 1577. The Protestant Prince of Orange was shot in the chest in 1584. France lost so many kings to the knife that it began to look like carelessness: Henri III stabbed in 1589, Henri IV stabbed in 1610. And everyone would know of the killing in England itself of two queens in particular: Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth’s mother, sent to the scaffold by Henry VIII, Elizabeth’s father, in 1536; and James’s mother, Mary Queen of Scots, executed on the orders of her cousin Elizabeth in 1587. In each case, the killing followed sustained reports of a treasonable conspiracy.

How would news of the conspiracies Carleton describes have circulated? Moira Goff, Curator of Printed Historical Sources at the British Library, describes how he did his research:

He would have acquired his material from a variety of sources.

Quite a lot of it would have been word of mouth, and some of it privileged word of mouth. His information would also have come from printed pamphlets or from manuscript newsletters, which would later be replaced by the printed newspapers then in their infancy. Shakespeare’s audiences were drawing on the same range of sources. The groundlings would have been much more reliant on the oral – have you heard the latest news? People further up the social hierarchy would have also been getting manuscript newsletters on a regular basis. For men of business, news was a staple of their work.

Anyone hearing rumours or reading pamphlets in the 1590s – newsletters of the sort Carleton later gathered together – would have recognized in Richard II’s catalogue of killed kings not the remote history of 200 years earlier, but something uncomfortably close to current affairs.

To the modern eye, Carleton’s lurid terrors can easily seem absurd. Yet if we look behind the bluster, his anthology makes disturbing reading, because Elizabeth and James were in fact frequent, one might almost say constant, targets of assassination. And had they been killed, the consequences for every person in the land would have been grave. Reading Carleton’s Remembrance, we can see there was a great deal to be frightened about.

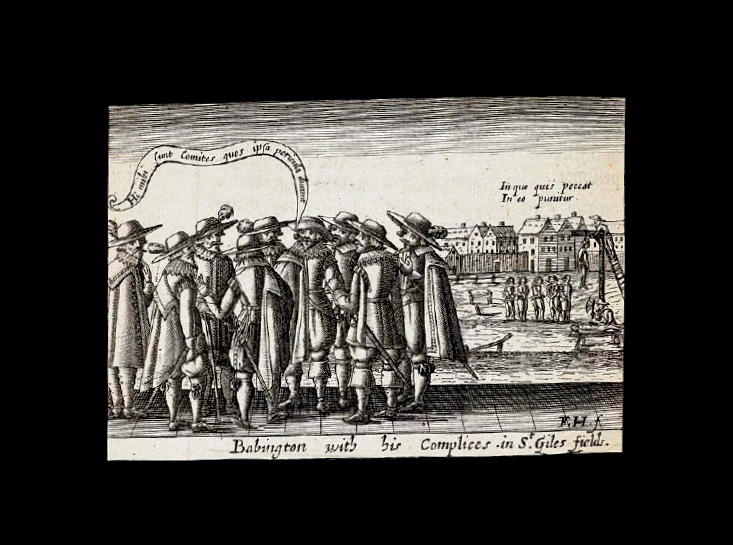

The book was enlivened by illustrations, twenty-one shockingly bad and crude woodcuts. We can watch William Parry, frozen with fear, finding himself unable to go through with his assassination attempt on a terrifying-looking Queen Elizabeth. Here are the Babington plotters, conspiring with Mary Queen of Scots against Elizabeth, blithely unaware of a grim execution taking place behind them – the fate that will soon be theirs. The pictures systematically underline the message of the text: Catholic traitors are everywhere, and they are plotting to destroy us.

The most sensational plot of the 1590s was the Lopez conspiracy, to which Carleton gives particular prominence. The mixture of political intrigue, paranoia about Spain, court gossip and xenophobia which lie behind the downfall of Roderigo Lopez reveals how powerful a force conspiracy anxiety had become in Elizabethan England. Lopez was a second-generation Portuguese immigrant, the son of a forcibly converted Jew. He was a wealthy and successful physician, serving the Queen as well as the Earl of Essex, one of Elizabeth’s favourites (see Chapter Seven). From about 1590 Lopez was in informal discussion with the Spanish ambassador to France, with a view to opening peace negotiations between England and Spain, but he seems to have gone well beyond his authority, enraging Essex by gossiping about his health and his political future. This was a serious mistake: when Essex came across evidence of Lopez’s unauthorized conversations, he claimed that his sources implicated Lopez in ‘a most dangerous and desperate treason’ to poison the Queen. The motive alleged was greed – a promised bribe of 50,000 crowns. Essex’s investigation was unremitting and ended with Lopez’s conviction and public execution. He was hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn on 7 June 1594.

‘Parry not able to kill the Queene’ from A Thankfull Remembrance. William Parry was one of the strange individuals occupying a grey world between exiled Catholic groups and the English government. Whether he was a spy or conspirator remains a mystery.

Lopez was in fact probably innocent: it appears that even the Queen had serious doubts about his guilt. But the case was hopelessly muddied by confusion, paranoia and double agents; and the momentum of events, and Essex’s determination to pursue a cause that so effectively heightened his own prestige, made Lopez’s fate inescapable.

‘Babington with his Complices in S. Giles fields’ from A Thankfull Remembrance. The plotters conspire, oblivious to the execution of a traitor behind them.

Carleton, in his account of the plot, describes the alien – the Jewish – nature of the traitor’s behaviour: ‘Lopez, like a Iew, did utterly with great oaths and execrations denie all the points, articles, and particularities of the accusation.’ But fascinatingly, Carleton feels the need to insist that behind Lopez’s Jewishness lies the even more alien, more threatening, power of the Catholic church: ‘This practise of poisoning…was brought into the Church by Popes, and reckoned among the sinnes of the Anti-christian Synagogue, and taught for Doctrine by the Romish Rabbies.’ Jews in league with the Pope: the ultimate Axis of Evil.

Susan Doran assesses Carleton’s constant focus on the Catholics as the main threat to the English state:

He was responding to a particular political circumstance of his time. The Catholics were considered to be the agents of the anti-Christ. It had started with the way that the burnings of Mary’s reign were being presented in England: Catholics were disloyal, they were erroneous, they were idolatrous, and if they were ever to get to power again, the Protestants would be in danger of their lives because they burned people. And the Saint Bartholomew massacre in 1572 in France again confirmed that impression. So there was an anxiety – almost like Islamophobia today, or at least as it was at the time of the Twin Towers – that there was an international conspiracy to overturn Protestantism, the true church, as well as the true monarch.

*

Carleton’s climax is the Gunpowder Plot – that famous attempt in 1605 by a handful of Catholic conspirators to blow up parliament and kill the King. He calls it a ‘blow to root out Religion, to destroy the state [and] the Father of our Country’. So outraged is Carleton, so potent is the event in his and his readers’ memories, that for once he does not limit himself to the usual suspects – generally the Spanish, intermittently the French, always the Pope. So hellish is the attempt to blow up parliament that this Gunpowder Plot can have come only from ‘the deepnesse of Satan’ himself.

Carleton aims to plant a fear of terrorism so all-pervasive that if the news he reports is true, England is like Hamlet’s Denmark, a kingdom on the cusp of dissolution – where foreign armies are about to invade, everyone is spying on everyone else, and a purloined letter can either save a man’s life, or send Babington and Lopez, or Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, to their deaths.

To most of us today, episodes like the defeat of the Armada, the Lopez incident and the thwarting of the Gunpowder Plot appear separate, distinct events. But Carleton knew they were all connected, all part of a sinister plot masterminded overseas and set in motion at home by covert enemy agents. For Shakespeare’s audience, these were the news stories they had heard endlessly repeated and discussed, the formative public events of their lifetime. In every Bolingbroke and every Brutus you saw not just a character from history whose motive you might ponder, but a rebel and a murderer of the sort that might any day turn your own world upside down. And in the great anonymous melting pot of the theatre, one of those secret agents, one of those covert assassins, might be standing right beside you – or even selling you an oyster.

Detail from a broadside on the Gunpowder Plot and the Guy Fawkes conspiracy, by Abraham Hogenberg, Cologne, 1606.