The ‘Armada Portrait’ of Elizabeth I, by George Gower, 1588–1600. England’s defeat of the Spanish Armada inspired this portrait and raised Elizabeth’s international status.

AFRICAN TREASURE

Elizabeth I was a monarch of many names – Good Queen Bess, Gloriana, the Virgin Queen and occasionally something much more exotic: ‘The Sultana Isabel, who has high position and majestic glory, constancy and steadiness, a rank which all her co-religionists, far and near, recognise, whose stature among the Christian people continues to be mighty and lofty’. The Sultana Isabel is, of course, Queen Elizabeth I as seen from far away – from Africa in 1600. This flattering description of her majestic glory, constancy and steadiness was given by one of her new allies on the world stage, Sharif Ahmad al-Mansur, the wealthy king of Morocco – far richer than Elizabeth herself – and a force to be reckoned with in both the Mediterranean and the Atlantic.

Sharif Al-Mansur’s comment on their Queen is a reminder that English play-goers in Shakespeare’s time were just beginning to be global citizens. They were proud of Francis Drake’s circumnavigation of the earth, credulous, willing listeners to tall stories of the sort of lands filled with ‘cannibals that each other eat / the Anthropophagi and men whose heads / do grow beneath their shoulders’, and eager readers of a new genre of thriller – traveller’s tales like Sir Walter Raleigh’s book of 1596, The Discovery of Guiana, possibly Shakespeare’s source for Othello’s stories.

This curiosity about an expanding, unsettling world was played out in the theatre. In The Merchant of Venice, a richly dressed, exotic figure sweeps on to the stage to woo the Italian heiress, Portia.

MOROCCO: Mislike me not for my complexion,

The shadowed livery of the burnished sun,

To whom I am a neighbour and near bred.

This eloquent sun-burnished man is the Prince of Morocco. He is the first of Shakespeare’s noble Moors and, what is more, the first non-villainous Moor to appear on the English stage. Even more surprising than his skin colour is that this man, whom Portia calls a ‘gentle’ Moor, is totally at ease with English currency:

MOROCCO: They have in England

A coin that bears the figure of an angel

Stampèd in gold – but that’s insculped upon;

But here an angel in a golden bed

Lies all within. Deliver me the key.

Here do I choose, and thrive I as I may!

Shakespeare reassuringly suggests that, even if the English know little of Morocco, this sympathetic prince already knows something about England – and quite a lot about its money.

This prince was a character entirely of Shakespeare’s invention – he does not appear in any of the earlier material that The Merchant of Venice drew on – and was probably inspired by England’s intensifying trading relations with Morocco in the 1590s. The divide between Christianity and Islam would have made his marriage to Portia unthinkable in the real world of sixteenth-century Europe, but on Shakespeare’s stage, Moorish royalty is associated not so much with an alien or hostile faith as with luxury and exotic riches: sugar, the finest horses and dizzying quantities of gold.

Nobody watching The Merchant of Venice would be the least bit surprised that the Prince of Morocco, asked to choose one of three caskets to win Portia’s hand in marriage, would go for the gold. West Africa was, as everybody knew, quite simply where gold came from: it was the source of pretty well every gold coin minted in England. Sharif al-Mansur controlled access to these huge gold supplies. From Timbuktu alone he took 600 kilograms of gold a year: predictably, he was dubbed al-dhahabi, the Golden One, and it was reported that ‘fourteen thousand hammers continuously struck coins at his palace gate’. While this is clearly a poetic exaggeration, one can nonetheless almost hear in that phrase the sound of al-Mansur’s money being minted.

The ‘Armada Portrait’ of Elizabeth I, by George Gower, 1588–1600. England’s defeat of the Spanish Armada inspired this portrait and raised Elizabeth’s international status.

OVERLEAF: Map of North Africa showing Marrakesh (Marocho), from Abraham Ortelius’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1570. Morocco, at the western end of the North African coastline, was always independent of the Ottoman Empire and played a role in the Atlantic as well as the Mediterranean.

This particular coin of Al-Mansur’s, now in the British Museum, is almost exactly the same size as a modern two-pence piece, although it is thinner and is, of course, made of solid gold. Both sides are covered with beautifully calligraphed Arabic script: ‘In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate,’ the central panel begins, then describes al-Mansur as ‘Commander of the Faithful’. The coin tells us both the place and the Islamic year of issue: ‘Struck in the city of Marrakesh, may God protect it, in the year one thousand and eight.’ That is the year we call 1600, by which time The Merchant of Venice had been playing for about five years.

Morocco was rich in saltpetre, the main raw material of gunpowder, as well as in sugar and gold, and in 1585 London merchants had established the Barbary Company to trade in north Africa. By the 1620s the English immigrant community in Morocco and neighbouring lands was substantial. English merchants and artisans took advantage of the region’s wealth and global trade links to make a good living, and there was a growing flow of people and goods going both ways between north Africa and England. But it was an unequal relationship: England paid more attention to rich Morocco than Morocco to England. Sharif al-Mansur began to take English power seriously only after the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. Morocco also was in a state of more or less permanent war with Spain, and England had suddenly emerged as a useful ally: to celebrate the Queen’s victory over their common enemy, the Sharif encouraged the English residents of Morocco to light festive bonfires.

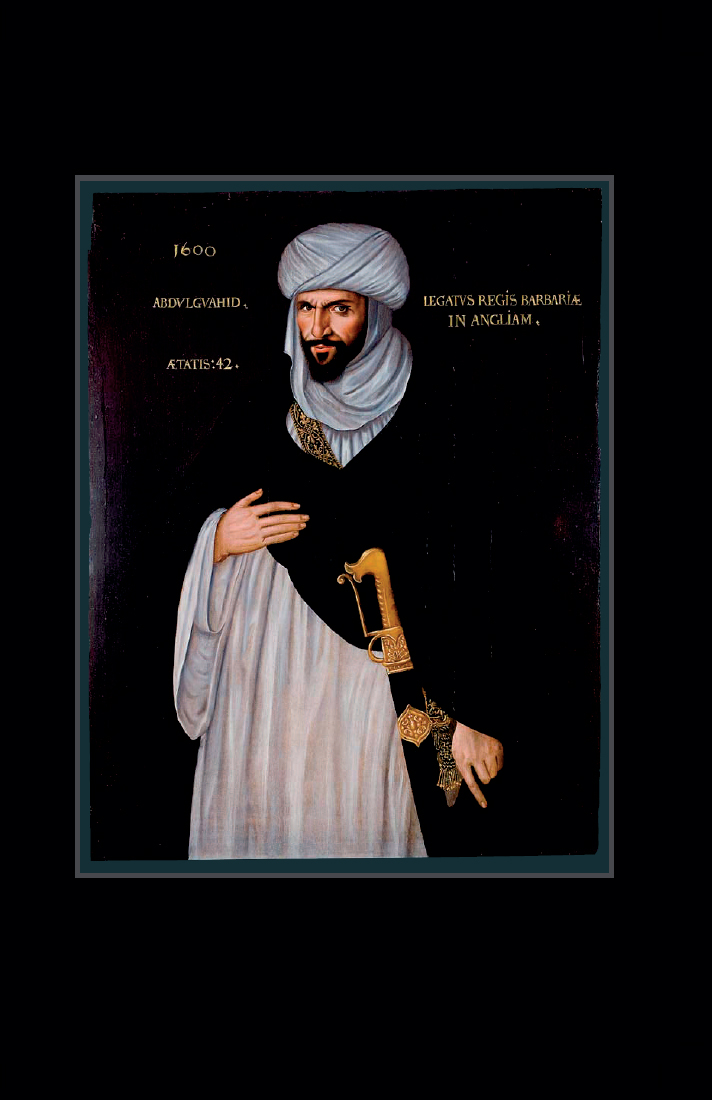

To foster the new alliance between the two countries, Al-Mansur also sent emissaries to England. Londoners were particularly struck by the splendid processions of the Moroccan ambassador, Abd al-Wahid bin Masoud bin Muhammad al-Annuri, and his retinue in 1600. For many it would have been their first glimpse not just of Africa, but of Islam. Kate Lowe, Renaissance historian at Queen Mary, University of London, explains:

That 1600 embassy was the first time that lots of Londoners would have seen Muslims in a group behaving as Muslims. It must have created an enormous impetus to understand more. There would have been a difference too between popular opinion and the official foreign policy line held at Court, because these people were allies against Spain. So at Court there was an acceptance of them, probably in a way that the people in the street did not see.

The Moroccan ambassador Abd Al-Wahid bin Masoud bin Muhammad Al-Annuri led an embassy to Elizabeth I in 1600. (Portrait by an unknown artist, 1600)

The street was potentially a great deal less friendly to foreigners, and treatment of Moors in England could be hostile – for there were some Moors on the London street. In 1595, English and Moroccan forces together had rescued north African galley-slaves from Spanish ships. Some were sent home to Morocco, but others were allowed to come to England. Despite the Queen’s interest in protecting her Moorish allies, Londoners protested, and the Moors eventually had to be expelled.

Shakespeare never actually uses the words Moroccan or Muslim. The standard Elizabethan word for a north African is ‘Moor’. Kate Lowe explains:

The word Moor sounds impressive, but it actually signifies very little. Originally it was the classical word to describe somebody that lived in Mauritania, the Roman province across the top of north Africa. After that it gained other meanings, one of which was black. It also later gained the meaning of a Muslim, but when it is used in Elizabethan England it is imprecise. That is in itself one of the reasons why that term ‘the Moor’ is used so much: it has resonance but not much substance, and you can hang so much off it.

One of the things you could easily hang off it was the popular xenophobic hostility that forced Elizabeth to expel the Moroccan galley-slaves, and Shakespeare does not shy away from this kind of racial antagonism. In Othello, not for the first time, he explores a contemporary London phenomenon by setting it in Venice. The villain Iago and the angry father of Desdemona – Othello’s white Venetian bride – indeed anyone hostile to Othello, use racial insults against the Moor: ‘thicklips’, ‘barbarian’ and ‘sooty’. These still shock today, as they were surely meant to then. Iago does not mince his words. Here he is telling Desdemona’s father that his daughter has eloped with Othello:

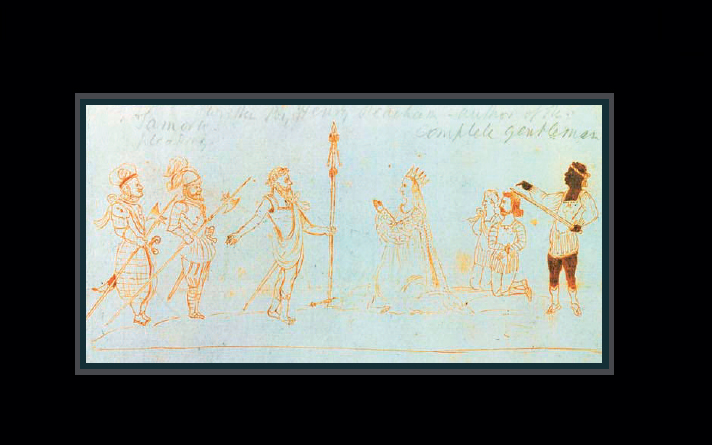

‘Recollection of Titus Andronicus’ attributed to Henry Peacham, around 1594. This is an impressionistic depiction rather than an actual moment in a performance, but it shows some conventions of stagecraft, including costume and Aaron the Moor’s extreme black makeup.

IAGO: Even now, now, very now, an old black ram

Is tupping your white ewe. Arise, arise,

Awake the snorting citizens with the bell,

Or else the devil will make a grandsire of you.

For Iago, Othello is not just black and oversexed, but diabolical, and, as the play goes on, Shakespeare accentuates Othello’s blackness. Yet for all the times he is associated with darkness, Othello is also praised: this general is ‘brave’, ‘noble’, ‘valiant’. The blacker his antagonists paint him, the more Shakespeare forces his audience to acknowledge Othello’s honour and integrity.

Desdemona falls for Othello as he is telling exotic stories of his African youth. One episode is particularly designed to win the young girl’s sympathy:

OTHELLO: Wherein I spake of most disastrous chances,

Of moving accidents by flood and field,

Of hair-breadth scapes i’th’imminent deadly breach,

Of being taken by the insolent foe,

And sold to slavery…

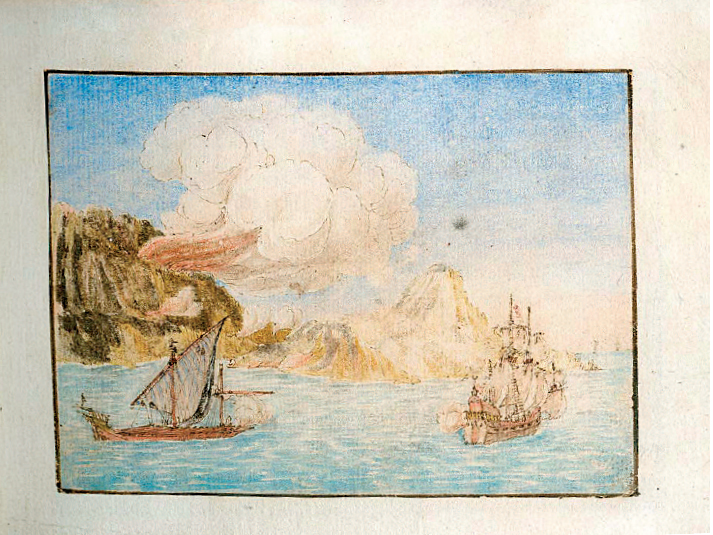

Othello, the great and valiant leader, was once himself a slave, sold after being taken prisoner. His story reminds us of something commonplace to the Elizabethans: the Mediterranean was a dangerous place of warfare, piracy, slavery and shipwreck, as the ships of the different seafaring powers – Venetian and Turkish, Genoese and Moroccan – fought for supremacy. And we know that one of these ships, passing from Morocco to northern Europe, carried this gold coin of Sharif al-Mansur – because it was found not in Morocco, but twelve miles off the coast of Devon, one of a hoard of 450 Moroccan gold coins found in Salcombe Bay in 1994. The South-West Archaeological Group, a team of amateur marine archaeologists and semi-professional divers, uncovered this astonishing treasure in a treacherous area of seabed, beset with strong currents and deep gullies. They found large quantities of sixteenth-century coins, gold ingots, earrings and pendants – all from Morocco – along with other artefacts and debris: lead weights, pewter tableware, ceramic fragments and decomposing iron. Apart from the coins, it is hard to tell what the many different pieces of gold are. Among the mass of 400-year-old Moroccan jewellery, there are no complete pieces. These are emphatically not jeweller’s goods for sale; rather they are chopped-up bullion, bits of gold intended to be melted down and reused. But the gold coins give us important information. Their inscriptions tell us that they were struck by several members of the Sa’did dynasty – of which al-Mansur was the most significant figure – that ruled Morocco from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-seventeenth centuries. The latest coin that we can date was issued by Sharif al-Walid, who ruled until 1636, so the shipwreck probably occurred shortly after that.

Pieces from the Salcombe Treasure, including coins, ingots and jewellery fragments, pendants and earrings of a type made in Morocco into the twentieth century.

This is inscrutable wreckage. There is not much about it that we know for certain: there are none of the usual signs of a boat that has gone down; no rudder, timber, deadeyes have been found, and there are no records of any ship lost in the area. Was this a trading ship on the way home from north Africa? Or was it perhaps a pirate ship? We know there were many such ships around – both English and Moroccan. Barbary pirates, in particular, took captives from ships on the high seas and from fishing vessels close to the English coast. Now and then they raided the mainland, sometimes literally dragging people from their beds and either enslaving them or holding them to ransom. In 1584, Richard Hakluyt reported that ships from Guernsey, Plymouth, Southampton and London were taken and their crews enslaved. The practice continued for decades. In 1631, 107 men, women and children were taken in Ireland; 20 per cent vanished – died or converted – before they could be ransomed.

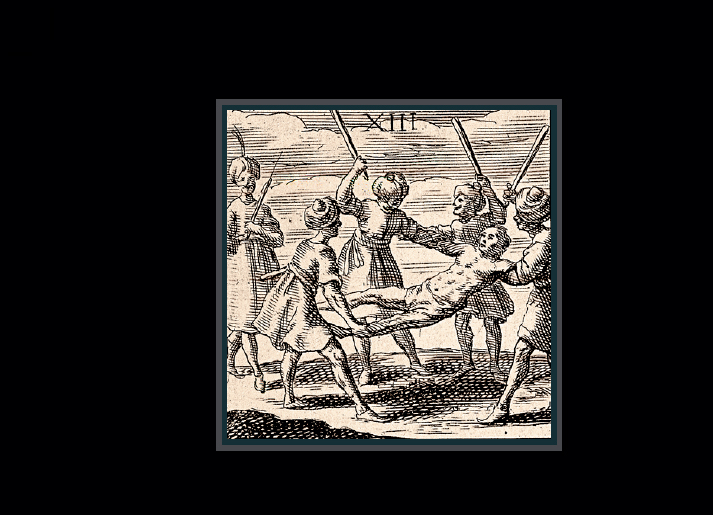

Scene 13 of twenty-two scenes of torture by Barbary pirates, from Pierre Dan’s Histoire de Barbarie, Paris, 1637.

When we think of pirates in stories, we tend to think of Long John Silver rather than anything more sinister. But for Shakespeare’s audience pirates were much closer to the murderous hijackers of our day, and piracy off the coast of England was a frightening, much-publicized possibility. The terrifying activities of these corsairs spawned a new literary genre in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England, known now as the captivity narrative: hair-raising and sword rattling tales of English victims seized by north African pirates. The mournfully and lengthily titled ballad of 1623 The Lamentable Cries of at least 500 Christians: Most of them Being Englishmen (Now Prisoners in Algiers Under the Turks) Begging God’s Hand That He Would Open the Eyes of All Christian Kings and Princes to Commiserate the Wretched Estate of So Many Christian Captives gives a compelling taste of the dangers at sea:

Being boarded so, and robbed then are they tied

On chains and dragged t’Argiers [i.e. Algiers] to feed the pride

Of a Mahumetan dog (eight in a row).

Each eighth man to the Argier king must go

And th’eighth part of what’s ta’en is still his prize;

What men he leaves are anyone’s who buys

And bids for them, for they then are led

To market and like beast sold by the head,

Their masters having liberty by law

To strike, kick, starve them, yet make them draw

In yokes, like oxen, and if dead they beat them

These captivity narratives told of attack, incarceration, derring-do and breathtaking escape. The stories of forced conversions and bestial savagery fed the xenophobia and religious hostility that coexisted, in the English popular mind, with hunger for the valuable and exotic goods of north Africa.

Pirates never took centre-stage for Shakespeare – he was, after all, a man from landlocked Warwickshire who seems never to have travelled abroad – but they are part of the elemental backdrop to sea travel in his plays. Pirates attack Hamlet en route to England, forcing him to return to Denmark, or they dash in and seize Marina in Pericles, leaving no doubt about their reputation for casual violence:

[Enter Pirates]

FIRST PIRATE: [to Leonine] Hold, villain! [Leonine flees]

SECOND PIRATE: [seizing Marina] A prize, a prize.

THIRD PIRATE: Half-part, mates, half-part. Come, let’s have her aboard suddenly.

[Enter Leonine]

LEONINE: These roguing thieves serve the great pirate Valdes,

And they have seized Marina. Let her go.

There’s no hope she will return; I’ll swear she’s dead

And thrown into the sea. But I’ll see further:

Perhaps they will but please themselves upon her,

Not carry her aboard. If she remain,

Whom they have ravished must by me be slain.

Pericles is one of Shakespeare’s later plays – one that he co-wrote in about 1607 or 1608. This scene is, perhaps, an acknowledgement of the dramatic upsurge of piracy that was sparked by the chaos and civil war in north Africa caused by the death of al-Mansur from plague in 1603. The seas were never more awash with Barbary pirates than during the first half of the seventeenth century.

Despite the heightened activity of corsairs in these decades, Kate Lowe thinks that the African treasure found in Salcombe Bay is unlikely to have been pirate gold:

I think it is far more likely to be trade. Morocco and England were only in contact because they were both united as being enemies of Spain. The English are sending timber so the Moroccans can build ships to fight against Spain, they are sending cannonballs, and sending guns. And the Moroccans are sending saltpetre to make gunpowder. They were probably trading in arms, and I suspect that the Moroccans had not got enough that the English wanted so they probably had to pay in bullion, and that is why some of it is broken up; it is just bits of jewellery and so on to get the required amount to buy the arms.

Whatever its precise history, the African treasure is evidence that England, like every other part of Europe, was now in economic, political and military terms unquestionably part of a global system. And Venice, as we saw in the last chapter, was one of its nerve centres. It is striking that in Othello the characters speak over thirty times of the ‘world’.

A battle between a Barbary ship and a European ship near the coast of Sicily, by Jacques Callot, 1620.

The Salcombe Bay treasure was a part of this new world system of sometimes violent exchange, and its gold coins show that Othello is much closer to the practical realities of Elizabethan life than we might think. Like Shylock or Cleopatra, Othello is not the distant outsider, but an example of the many encounters between the English and Africans, Arabs and others. A surprisingly large number of people around 1600 would have thought of Good Queen Bess as the mighty and lofty Sultana Isabel.