IT CAME TO ME OUT OF NOWHERE, WITHOUT THE APPARENT AID OF LOGIC, THAT WHAT I WANTED MOST IN LIFE JUST THEN WAS TO WALK FROM ONE END OF CALIFORNIA TO THE OTHER.

—The Thousand-Mile Summer, Colin Fletcher

Backpacking isn’t difficult, but it does require both physical and mental preparation. Every year, first-time hikers set off along the trail unfit, ill equipped, and with unrealistic expectations. Many of them never venture into the wilderness again. The better your planning, the more enjoyable your trip will be. You need not know exactly how far you’ll walk each day, or precisely where you’ll camp each night (though such detailed planning is useful for beginners), but you should know your capabilities and desires well enough to tailor your trip to them. Setting out to carry 65 pounds twenty-five miles a day through steep, mountainous terrain just about guarantees exhaustion, frustration, and disappointment unless you are extremely fit and know beforehand that you can do it.

Backpacking requires fitness. You need aerobic, or cardiovascular, fitness to walk and climb all day without having your heart pound and your lungs gasp for air. Without muscular fitness, particularly of the legs, you’ll be stiff and aching all over on the second day out. Also, if you set out unfit, you’re much more susceptible to strains and muscle tears.

Getting fit takes time. I know people who claim they’ll get fit over the first few days of an annual backpacking trip. They usually suffer for most of the walk; yet with a little preparation, they could enjoy every day.

The best way to train for carrying heavy loads over rough terrain is to carry heavy loads over rough terrain—what sports trainers call specific training. Although this isn’t always practical, you’d be surprised what you can do if you really want to, even if you live and work in a city. In Journey Through Britain, John Hillaby wrote that he trained for his 1,100-mile, end-to-end walk across Britain by spending the three months before the trip walking the six miles “from Hampstead to the City [London] each day and farther at the weekends. On these jaunts I carried weight lifters’ weights sewn high up in a flat rucksack that didn’t look too odd among people making their way to the office in the morning.”

At the very least, spend a few weekends getting used to walking with a load before setting off on a longer trip. Walk as much as you can during the week—including up and down stairs. Brisk strolls or runs in the evening help too, especially if there are hills. In fact, trail running in hilly country is probably the best way to improve both your aerobic fitness and your leg power in a short time.

I trained at a fitness center once, before a through-hike of the Canadian Rockies. For six months I did hour-long circuit sessions on the weight machines three times a week and hour-long runs on the days between, with one day off a week. It helped, but probably no more than if I’d hiked regularly with a pack and exercised in the woods and fields, which I prefer. I haven’t followed an exercise program since. If you want to do so, however, The Outdoor Athlete, by Steve Ilg, is worth reading (see his Web site, wholisticfitness.com). The book includes programs for “mountaineering and advanced backpacking” and “recreational hiking and backpacking.” The main thing I learned from fitness center training was that you need rest from strenuous exercise and that you need to pace yourself. I’d never heard of overtraining before, having never regarded backpacking or hiking as a “sport.” But once I discovered that pushing yourself too hard results, unsurprisingly, in excess stress to the body and reduced performance, I understood why, after hiking all day every day for two weeks or more, I often felt tired and run-down instead of superfit. Now on walks longer than two weeks I aim to take a rest day every week to twelve days. I don’t stick to a rigid timetable—a day off every week, say—but rather pay attention to my body and my mind. If I feel lethargic or uninterested, develop aches and pains, or find myself being clumsy and careless, I know I need to rest. Resting while training is important—if you force yourself to train hard every day because you’ve got a big trip coming up, you may burn out before the hike starts.

Looking across the Merced River Canyon to Red Peak, Yosemite Wilderness.

After my brief bout with the fitness center, I abandoned formal training and returned to short, brisk hikes in the local woods and fields, the occasional 5- to 10-mile cycle ride, and as an aim if not in reality, at least one full day a week walking or skiing in the mountains. This is apart from the two- to three-day backpacking trips I try to take once a month or so between longer walks.

If you haven’t exercised for some time, return to it gradually, especially if you’re over thirty-five. Preparing for a walk takes time anyway. You can’t go from being unfit to toting a heavy load all day in a week or even a month.

While the simple act of putting one foot in front of the other seems to require no instruction or comment, there are, in fact, good and bad ways to walk, and good and bad walkers. Good walkers can walk effortlessly all day, while bad ones may be exhausted after a few hours.

To make walking seem effortless, walk slowly and steadily, finding a rhythm that lets you glide along and a pace you can keep up for hours. Without a comfortable rhythm, every step seems tiring, which is one reason that crossing boulder fields, brush-choked forest, and other broken terrain is so exhausting. Inexperienced walkers often start off at a rapid pace, leaving the experienced plodding slowly behind. As in Aesop’s ancient fable of the tortoise and the hare, slower walkers often pass exhausted novices long before a day’s walk is complete.

The ability to maintain a steady pace hour after hour has to be developed. If you need a rest, take one; otherwise you’ll wear yourself out.

The difference between novices and experts was graphically demonstrated to me when I was leading backpacking treks for an Outward Bound school in the Scottish Highlands. I let the students set their own pace, often following them or traversing at a higher level than the group. But one day the course supervisor, an experienced mountaineer, turned up and said he’d lead the day’s walk—and he meant lead. Off he tramped, the group following in his footsteps, while I brought up the rear. Initially, we followed a flat river valley, and soon the students were muttering impatiently about the supervisor’s slow pace. The faint trail began to climb after a while, and on we went at the same slow pace, with some of the students close to rebellion. Eventually we came to the base of a steep, grassy slope with no trail. The supervisor didn’t pause—he just headed up as if the terrain hadn’t altered. After a few hundred yards, the tenor of the students’ response changed. “Isn’t he ever going to stop?” they complained. One or two fell behind. Intercepting a trail, we turned up it, switchbacking steadily to a high pass. By now some of the students seemed in danger of collapse, so I hurried ahead to the supervisor and said they needed a rest. He seemed surprised. “I’ll see you later then,” he said, and started down, his pace unaltered, leaving the students slumping in relief.

Mount Beulah and the West Fork Blacks Fork valley, High Uinta Wilderness, Utah.

This story also reveals one of the problems of walking in a group: each person has his or her own pace. The best way to deal with this is not to walk as a large group but to establish pairs or small groups of walkers with similar abilities, so people can proceed at their own pace, meeting up at rest stops and in camp. If a large group must stay together, perhaps because of bad weather or difficult route finding, let the slowest member set the pace, perhaps leading at least some of the time. It is neither fair nor safe to let the slowest member fall far behind the group, and if this happens to you, you should object.

The ability to walk economically, using the least energy, comes only with experience. If a rhythm doesn’t develop naturally, it may help to try to create one in your head. I sometimes do this on long climbs if the right pace is hard to find and I’m constantly stopping to catch my breath. I often chant rhythmically any words that come to mind. When I can remember them, I find the poems of Robert Service or Longfellow are good. I need to repeat only a few lines: “There are strange things done in the midnight sun / By the men who moil for gold; / The Arctic Trails have their secret tales / That would make your blood run cold” (from Service’s “The Cremation of Sam McGee”). If I begin to speed up, I chant out loud, which slows me down. It is of course impossible to walk for a long time at a faster-than-normal pace, but walking too slow is surprisingly tiring, since it is hard to establish a rhythm.

Once in a while all the aspects of walking come together, and then I have an hour or a day when I simply glide along, seemingly expending no energy. When this happens, distance melts under my feet, and I feel I could stride on forever. I can’t force such moments, and I don’t know where they come from, but the more I walk, the more often they happen. Not surprisingly, they occur most often on really long treks. On such days, I’ll walk for five hours and more without a break, yet with such little effort that I don’t realize how long and far I’ve traveled until I finally stop. Rather than hiking, I feel as though I’m flowing through the landscape. I never feel any effects afterward, except perhaps greater contentment.

How far can I walk in a day? This is a perennial question asked by walkers and nonwalkers alike. The answer depends on your fitness, the length of your stride, how many hours you walk, the weight you’re carrying, and the terrain. There are formulas for making calculations, including a good one proposed in the late nineteenth century by William W. Naismith, a luminary of the Scottish Mountaineering Club. Naismith’s formula allows one hour for every 3 miles, plus an extra half hour for every 1,000 feet of ascent. I’ve used this as a guide for years, and it seems to work; a 15-mile day with 4,000 feet of ascent takes me, on average, eight hours including stops. Of course, 15 miles on a map will be longer on the ground, since map miles are flat miles, unlike most terrain. As slopes steepen, the distance increases.

The time I spend between leaving one camp and setting up the next is usually eight to ten hours, not all of it spent walking. I once measured my pace against distance posts on a flat, paved road in the Great Divide Basin during a Continental Divide hike. While carrying a 55-pound pack, I went about 3¾ miles an hour. At that rate I would cover 37 miles in ten hours if I did nothing but walk (and the terrain was smooth and flat). In practice, however, I probably spend no more than seven hours of a ten-hour day walking, averaging about 2½ miles an hour if the terrain isn’t too rugged. That speed, for me, is fast enough. Backpacking is about living in the wilderness, not racing through it. I cover distance most quickly on roads—whether tarmac, gravel, or dirt—because I always want to leave them behind as soon as possible.

On Dead Horse Pass, High Uinta Wilderness, Utah.

How far you can push yourself to walk in a day is less important than how far you are happy walking in a day. This distance can be worked out if you keep records of your trips. I plan walks based on 15 miles a day on trails and over easy terrain. For difficult cross-country travel, I estimate 12 miles a day.

When planning treks, it also helps to know how far you can walk over a complete trip. You can get an idea by analyzing your previous walks. For example, I averaged 16 miles a day on the 2,600-mile Pacific Crest Trail (PCT), a 1,600-mile Canadian Rockies walk, a 1,300-mile Scandinavian mountains walk, and an 800-mile Arizona Trail hike and 16¾ miles a day on the 3,000-mile Continental Divide, which seems amazingly consistent. A closer look, however, reveals that daily distances varied from 6 to 30 miles, and the time between camps varied from three to fifteen hours. All these walks were mainly on trails. My 1,000-mile Yukon walk was mostly cross-country, and on that my average dropped to 12½ miles a day.

One problem with a two-week summer backpacking trip is that many people spend the first week struggling to get fit and the second week turning the first week’s efforts into hard muscle and greater lung power. By the time they’re ready to go home, they’re at peak fitness. The solution is to temper your desires. It’s easy in winter to make ambitious plans for the next summer’s hikes that fall apart the first day out as you struggle to carry your pack half the distance you intended. On all walks, I take it easy until I feel comfortable being on the move again. This breaking-in period may last only a few hours on a weekend trip or a couple of weeks on a long summer trek. On two-week trips, it’s a good idea to take it easy the first two or three days by walking less distance than you hope to cover later in the trip, especially if you’re not as fit as you intended to be.

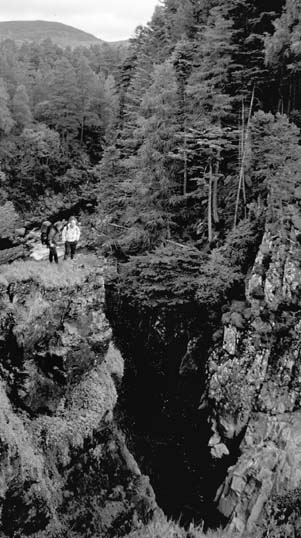

Backpackers at a remote overlook.

In theory, pedometers measure how far you travel during a specific time. But all pedometers work by converting the number of steps taken into distance, and this works only if your strides are regular. In the wilderness, with its ups and downs, bogs, scree, boulders, and logs, maintaining a regular stride hour after hour is difficult. I’ve tried pedometers, but they’ve never produced any reliable figures. (Note that a GPS unit—see pages 367–72—can measure how far you’ve traveled much more accurately than a pedometer.)

It’s customary to advise hikers never to go alone, but I can hardly do that since I travel solo more often than not—I feel it’s the best way to experience the wilderness. Only when I go alone do I achieve the feeling of blending in with the natural world and being part of it. The heightened awareness that comes with solo walking is always absent when I’m with others. Solitude is immeasurably rewarding. Going alone also gives me the freedom of self-determination. I can choose to walk twelve hours one day but only three the next, or to spend half a day watching otters or lying in the tent wondering if the rain will ever stop without having to consult anyone else. This is more than just freedom or what might seem self-indulgence, though. At a deeper level it’s about finding your natural rhythm, the one where your body and mind work best and which is unique to you, and attuning it to the rhythms of nature. Your rhythm is most obvious when you’re walking, but it is there when you eat, sleep, and rest. You can slip into this rhythm much more easily alone than with others, when it may not even be possible.

Of course, solo walking has its dangers, and it’s up to you to calculate what risks you’re prepared to take. When crossing steep boulder fields or fording streams, I’m always aware that if I slip there’s no one to go for help. The solo walker must weigh every action carefully and assess every risk. In the foothills of the Canadian Rockies I once spent eight days struggling cross-country through rugged terrain. I was constantly aware that even a minor accident could have serious consequences, especially since I was also way off the trail. Such situations demand greater care than trail travel, where a twisted ankle may mean no more than a painful limp out to the road and potential rescuers may not be too far away.

The wilderness is far safer than civilization. Having a car accident on your way to the wilderness is more likely than getting injured while you’re there.

You always should leave word with somebody about where you are going and when you’ll be back, especially if you’re going out alone. The route details you leave may be precise or vague—but you must leave some indication of your plans with a responsible person. If you’re leaving a car anywhere, you should tell someone when you’ll be back for it. This isn’t a problem in places where you must register a trail permit, but elsewhere a parked car could cause concern or even lead to an unnecessary rescue attempt if it’s there for many days. Unfortunately, leaving a note on your car is an invitation to thieves.

Whenever you’ve said you’ll let someone know you’re safe, you must do so. Rescue teams have spent too many hours searching for hikers who were back home or relaxing in a café because someone expecting word didn’t receive it.

Different hiking styles produce different outlooks—philosophies, even, if that’s not too grand a word for a simple pleasure. Some hikers stride along the trail, aiming for the maximum mileage per hour, day, or week. Others dash up and down the peaks, bagging as many summits as possible. The more contemplative meander through forests and meadows, studying flowers, watching clouds, or simply staring into the distance when the spirit moves them.

The term slackpacker was first coined to describe Appalachian Trail (AT) hikers who, while intent on walking the entire 2,150 miles, nevertheless planned on doing it as casually as possible. Now it’s often used to mean hiking without a heavy pack, which is accomplished by having gear and supplies transported to road crossings along the route. In this book I use the original meaning.

One of the walkers the description was first applied to holds the record for the slowest continuous Appalachian Trail walk: o.d. coyote (his “trail” name—an AT tradition—which has become his real name) took 263 days for his hike, an average of 8 miles a day.

In the September–October 1994 issue of Appalachian Trailway News, the journal of the Appalachian Trail Conference, o.d. coyote described slackpacking as an “attempt to backpack in a manner that is never trying, difficult, or tense, but in a slowly free-flowing way that drifts with whatever currents of interest, attraction, or stimulation are blowing at that moment” and wrote that slackpacking means escaping from “our culture’s slavish devotion to efficiency” and banishing “the gnawing rat of goal-orientation” by relearning how to play.

The opposite of slackpacking is fastpacking, or powerhiking, which maximizes daily mileage by walking for long hours with only a few short stops. It can mean speed hiking, too, where you hike as fast as possible, but speed isn’t the main aim—distance is. Fastpackers usually travel ultralight so they don’t need to rest often. They can cover more miles and therefore see more in a weekend or hike long trails in half the normal time. Ultimately fastpacking merges into trail running, so I was interested but not surprised to hear from one fastpacker that he’d run sections of the Appalachian Trail while through-hiking. Fastpacking and trail running may sound like tough, painful work, but for devotees there are many rewards. Hearken to the words of long-distance runner John Annerino, who has run the length of the Grand Canyon on both the north and south sides of the Colorado River: “And so I run, run like the wind, the wind pushing me across a rainbow of joy that now extends from one end of the Grand Canyon to the other. The running is a fantasy come alive; there is no effort, nor is there the faintest hint of pain. It is pure flight” (Running Wild). And British long-distance wilderness runner Mike Cudahy, who has run the 270-mile Pennine Way in England in under three days, offers this explanation for the “indescribable joy” that can occur on a long, hard run: “Perhaps the artificiality of a conventional and sophisticated society is stripped away and the simple, ingenuous nature of a creature of the earth is laid bare.”

Fastpacking and slackpacking are extremes. Most backpackers do neither, but everyone tends toward one or the other. Is one better? No. Different approaches are right for different people. There’s nothing wrong with walking the Appalachian Trail at 8 miles a day or running the length of the Grand Canyon in a week—as long as it satisfies and rejuvenates you and you respect nature and the land you are moving through. There’s no need for hikers to criticize each other for being too fast or too slow, for bagging peaks or collecting miles, for going alone or in large groups, for sticking to trails or not sticking to trails—for being, in fact, different from the critic.

I’ve tried most forms of wilderness walking and running, including attempting 100 miles in forty-eight hours and more than one two-day mountain marathon race. I’ve also wandered mountains slowly, averaging maybe 10 miles a day. Overall, I prefer the latter approach, but I wouldn’t call it superior. At times during long runs I’ve felt flashes of what Annerino describes, but these moments have never made up for my exhaustion and aching limbs. I gain the greatest fulfillment on backpacking trips lasting weeks at a time. How far I walk on such trips doesn’t seem to matter. It’s living in the wilds twenty-four hours a day, day after day, that’s important to me. I still enjoy walking fast and am quite happy doing 25 to 30 miles a day in easy terrain with a light load, but I don’t like having to do so. I like to know I can stop whenever I want, for as long as I want.

There are practical reasons for being able to cover long distances at times, though. Being able to travel fast if necessary can be important for safety. Having that ability in reserve means you are always hiking within your capabilities, so if a storm arises or you find your planned campsite a morass, you’ll have the extra energy and strength to keep going. And if the weather or unforeseen hazards—difficult river crossings, blocked trails—slow you down, being able to hike fast for a day or two can mean finishing the trip when you intended without arriving exhausted and footsore.

To experience all that walking has to offer, it’s worth trying different approaches. If you generally amble along, stopping frequently, try pushing yourself occasionally to see what it feels like. If you always zoom over the hills, eating up the miles, then slow down once in a while, take long rest stops, look around.

In its simplest form, planning means packing your gear and setting off with no prescribed route or goal in mind. This is what I sometimes do in areas I know well, especially when the weather might affect any route plans I did make. I’ve even done it in areas I’ve never visited before so that I could go wherever seemed interesting. Once, owing to an eleventh-hour assignment to attend and write about a mountain race, I found myself in the Colorado Rockies with ten days to spare and no plans. Having no route, no clear destination, worried me at first. Where would I go, and why? But there was freedom in not knowing. I didn’t have to walk a certain distance each day. There were no deadlines, no food drops, no campsites to book in advance. I could wander at will. Or not wander. The Colorado Rockies are ideal for such an apparently aimless venture, because their small pockets of wilderness are easy to escape when you need to resupply or want a day or two in town.

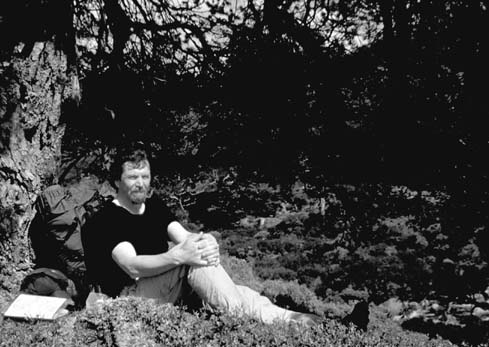

Contemplating the wild.

Usually, though, a little more planning is required. Guidebooks, maps, Web sites, DVDs, CD-ROMs, and magazine articles can all provide information on where to go. A Web search with Google is a good place to start. Once you’ve selected an area, you can obtain up-to-date information from the land managers—the National Park Service, the Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, or state forest or park services.

Squaw Lake, John Muir Wilderness, High Sierra.

There is no such thing as too much information. The problem is sorting out what is useful from what is irrelevant. Information on water sources may be unnecessary in wet coastal mountains, but it’s critical in the desert. The Internet can quickly overwhelm you with masses of information. Start to sift through it though, and you’ll find that much is not of value for your hike. Consider whom the site is aimed at; often it’s not hikers. Many Web sites are updated regularly, some daily. Up-to-date local knowledge is still important, however. Nothing beats talking to someone who hiked over that ridge last week or drank from that spring yesterday. In really remote areas like the Yukon, local knowledge is invaluable. On my walk through that area, I changed my route several times based on information from locals.

For the initial route planning I use small-scale (1:250,000) maps covering large areas before purchasing the appropriate topographic maps and working out a more detailed line. DeLorme’s Atlas and Gazetteer volumes—one for each state of the United States—and similar volumes are excellent for an overview of an area. Mapping software can be used too, though I find it easier to plan routes on a large paper map than on a screen, probably because I’ve had years of practice. When planning I’m always aware, however, that cross-country routes may be impassable or that a far more obvious way may show itself, so I don’t stick rigidly to my prehike plans. It’s easy to draw bold lines across a paper map, carried away by the excitement of anticipation, without considering the reality of trying to walk the route.

One of the big problems with planning a hike of more than a few days is resupplying. For popular trails like the Appalachian and the John Muir, there are regularly updated lists of facilities like post offices and grocery stores. There are even companies that will ship food parcels to you. Hikers may be rare or even unheard of in other places, however, so it’s always best to write and ask about amenities.

Most areas don’t require permits, but many national parks and some wilderness areas with easy access do. The number of permits issued may be severely restricted in the most popular places, making it essential to apply long before your trip. If you want to backpack popular trails in national parks like Grand Canyon or Yosemite, you need to apply for a permit many months in advance and must be flexible about your route. Whatever you think about limiting numbers by permit (I would rather see access made more difficult by long walk-ins in place of entry roads and backcountry parking lots), it means that even in popular areas, you won’t meet too many people. There remain vast areas of less-frequented wilderness where permits aren’t needed, and even the trails most crowded in summer are usually quiet out of season, making permits much easier to obtain. On a two-week ski-backpacking trip through the High Sierra in May, my group encountered only two other parties, both on the same day. Where good campsites are rare, such as the Grand Canyon, you can camp only in certain spots and must have a permit for each site in the most visited areas, though wild camping is allowed elsewhere in the park. It’s best to check whether permits are needed before making firm plans for an area.

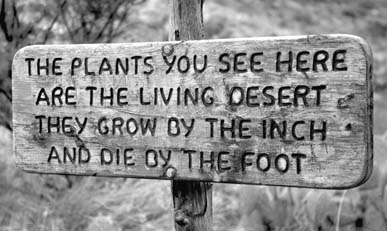

Advice to tread softly, Grand Canyon, Arizona.

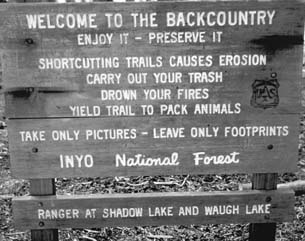

Backcountry advice, Inyo National Forest, California.

Many backpackers dream of hiking a long-distance trail in one continuous journey. The big three National Scenic Trails, known as the Triple Crown, are the 2,100-mile Appalachian Trail, the 2,600-mile Pacific Crest Trail, and the 3,100-mile Continental Divide Trail (CDT). Hiking such mammoth distances is a major undertaking. A few people have set off on one of these with no more than a hazy idea of the route or what to expect yet have completed the whole trail. But far more give up within the first few days or weeks—and this includes those who do some planning. The numbers succeeding have increased since the previous edition of this book, however. Then, just 15 to 20 percent of PCT through-hikers completed the trail. Now, of the three hundred or so who set off each year, some 60 percent finish (information from the Pacific Crest Trail Association). Figures for the much more popular Appalachian Trail aren’t so good. Of the two thousand or so through-hikers each year, less than 20 percent reach the end (information from the Appalachian Trail Conference).

The U.S. offers many backpacking opportunities.

There are various reasons for failure. Heavy packs, sore feet, exhaustion, overly ambitious mileage goals, unexpected weather, terrain, and trail conditions are the most common. Detailed planning is advisable for a long-distance hike, especially one that will take several months. A surprising number of hikers set off each spring for Mount Katahdin, Maine (the northernmost point of the AT), having done no more than a few weekend hikes, if that. This in itself ensures a high failure rate. A gradual progression—an apprenticeship, in fact—should precede a multimonth trip. Before attempting one of the big three, try hiking a shorter but still challenging trail, such as the 211-mile John Muir Trail in California, the 471-mile Colorado Trail, or the 265-mile Long Trail in Vermont. My first solo distance hike, a seventeen-day, 270-mile trip along Britain’s Pennine Way, followed several years of two- to five-day trips. Two years later, I made a 1,250-mile Britain end-to-end hike. Then, after another three years of shorter trips, I set out on the Pacific Crest Trail. I still made lots of mistakes, but I had enough knowledge and determination to finish the walk. If it had been my first distance hike, I doubt I would have managed more than a few hundred miles.

Preparation for a long trek doesn’t mean just dealing with logistics—knowing where to send food supplies, where stores and post offices are, how far you can realistically walk per day—it also means accepting that at times you will be wet, cold, or hungry and the trail will be hard to follow. Adventures are unpredictable by definition. Every long walk I’ve done included moments when I felt like quitting, but I’ve always continued, knowing the moment would pass. If the time ever comes when the moment doesn’t pass, I’ll stop. If backpacking isn’t enjoyable, it’s pointless. Completing the trail doesn’t matter—it’s what happens along the way that’s significant.

For me, the ultimate backpacking experience is to spend weeks or months in wilderness areas without long-distance trails, or sometimes without any trails at all. Walking a route of my own is more exciting and satisfying than following a route someone else has planned.

Planning such a walk can be difficult, however. Compiling information takes time, and there are always gaps. The easiest approach is to link shorter trails, as I did for the southern half of my walk the length of the Canadian Rockies. Even there, though, I had to travel cross-country on one trailless section.

First, of course, you have to decide where you want to start and finish. This inspiration can come from the nature of the land, from the writings of others, and occasionally from photographs. My first long-distance walk from Land’s End to John o’Groat’s was inspired by John Hillaby’s Journey Through Britain. Soon after that walk I read Hamish’s Mountain Walk, by Hamish Brown, about the first continuous round of the Munros, Scottish mountains over 3,000 feet high. Brown’s walk inspired a couple of 500-mile walks in the Scottish Highlands, but the idea of a really long walk there was put aside in favor of other ventures. A PCT walk was inspired by a slide show of the Yosemite backcountry and by Colin Fletcher’s The Thousand-Mile Summer. On the PCT, I learned of the CDT, so it was that trail I hiked next. On a ski-backpacking trip in the Canadian Rockies I came upon Ben Gadd’s Handbook of the Canadian Rockies and read that no one had hiked the length of the range. Another dream was born. A later Yukon trip was, in a sense, a continuation of this walk into an area I’d read about in the writings of Jack London and Robert Service.

I always thought that one day I would hike all the Munros in one go. The spur that turned a vague thought into a concrete plan came from another book, Andrew Dempster’s fascinating The Munro Phenomenon, a sentence of which flew off the page: “It is interesting and almost strange that no one has yet attempted all the Munros and Tops in a single expedition.” I knew instantly that I wanted to try this—a round of all 517 of Scotland’s 3,000-foot summits. A year later I set off. (For the story of this walk, see my book The Munros and Tops.)

The thought of being the first to do something lends excitement and adventure to an expedition. Yes, the heart of any backpacking trip is spending weeks at a time living in wild country, and it is the great pleasure and satisfaction of doing this that sends me back again and again. But a goal gives a walk focus—a shape, a beginning, and an end.

The initial buzz of excitement eventually gives way to a sober assessment of what is involved. This is the point at which ventures come closest to being abandoned. The planning often seems more daunting than the walk itself, but once begun, it’s usually enjoyable.

The Scottish summits walk and the one that preceded it, a 1,300-mile traverse of the mountains of Norway and Sweden, both took place in mostly wet and windy weather. In between them I had spent two weeks hiking in the Grand Canyon. Having had enough of dampness and mist and loving the sharp clarity and burning sunshine of the Southwest, I decided my next long hike would be the 800-mile Arizona Trail, a route still incomplete in many places. On the Scottish and Scandinavian hikes I never carried more than a pint of water, and mostly I carried none. In Arizona I often carried a gallon and sometimes three gallons. (The story of that hike is told in Crossing Arizona.) Water went from being an insignificant concern during the planning stages to the most important factor. (For more on long-distance hiking, see my book The Advanced Backpacker.)

Spring backpacking by the Dubh Lochain, Beinn A’Bhuird, Cairngorm National Park, Scotland.

Moose, Kidney Lake, High Uinta Wilderness, Utah.

Planning a hike, whether for a weekend or a summer, takes time and energy, and the adventure itself can vanish in a welter of lists, logistics, maps, and food. This is only temporary, of course. When you take that first step, all the organization fades into the background. Then it’s just you and the wilderness.