[I]N CASE OF HEAVY RAIN I PROPOSED TO MAKE MYSELF A LITTLE TENT, OR TENTLET, WITH MY WATERPROOF COAT, THREE STONES, AND A BENT BRANCH.

—Travels with a Donkey, Robert Louis Stevenson

Silence. A ragged edge of pine trees, black against a starry sky. Beyond, the white slash of a snowy slope on the distant mountainside. A cocooned figure stirs, stretches. A head emerges from the warm depths, looks around in wonderment, then slumps back to sleep. Hours pass. The stars move. An animal cry, lonely and wild, slices through the quiet. A faint line of red light appears in the east as the sky lightens and a faint breeze ripples the grasses. The figure moves again and sits up, still huddled in the sleeping bag, then pulls on a shirt. A hand reaches out, and the faint crack of a match being struck rings around the clearing. A light flares, then a soft roar breaks the stillness and a pan is placed on the stove’s blue flame. The figure draws back into its shelter, waiting for the first hot drink and watching the dawn as the stars slowly fade and the strengthening sun turns the black shadows into rocks and, farther away, cliffs, every detail sharp and bright in the growing light. The trees turn green again as warm shafts of golden sunlight illuminate the silent figure. Another day in the wilderness has begun.

Nights and dawns like that—and ones when the wind rattles the tent and the rain pounds down—distinguish backpacking from day walking and touring from hut to hut, hostel to hostel, or hotel to hotel. On all my walks I seek those moments when I feel part of the world around me, when I merge with the trees and hills. Such times come most often and last longest when I spend several days and nights living in the wilderness.

We need shelter from cold, wind, rain, insects, and sometimes sun. It’s a necessary evil. I use a shelter only when I have to, which admittedly is much of the time. But if I can sleep outside reasonably comfortably with no barrier between me and the world except a sleeping bag, I do.

The kind of shelter you need depends on the terrain, the time of year, and how spartan you’re prepared to be. Some people like to sleep in a tent every night; others use one only in the worst conditions. Polar explorer Robert Peary never used a tent or a sleeping bag but slept outside in his furs, curled up beside his sled. Most mortals require a little more shelter than that. In ascending order of protection, shelters include bivouac bags, tarps, tents, and huts and lean-tos, with snow shelters as a snow country option.

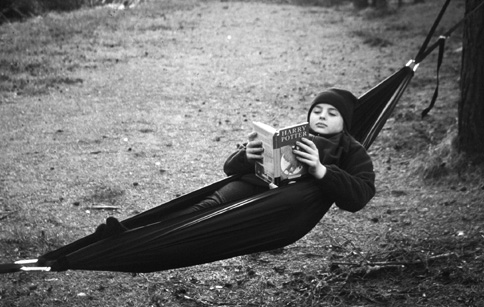

Sleeping out under the stars, known as bivouacking, is the ideal way to spend a night in the wilderness. The last things you see before you fall asleep are the stars and the dark edges of trees and hills. At dawn you wake to the rising sun and watch color and movement return to the world. These most magical times of day are lost to those inside a tent.

Of course, since the weather can be unkind and is often changeable, instead of sunlight you may wake up to cold raindrops on your face. The simplest way to cope with weather changes is to use a waterproof bivouac bag, also called a bivy bag or a sleeping bag cover. This is a waterproof “envelope” you can slip your sleeping bag into when the weather turns wet or windy. More sophisticated (and usually heavier) designs have short poles or stiffened sections at the head to keep the bag fabric off your face. (Bags with poles at each end are really minitents, so I’ll explore them later, in the Tents section.)

In dry places like the Grand Canyon, a shelter may not be needed.

A chilly morning in the Sonora Desert, Arizona Trail, Tortilla Mountains, Arizona.

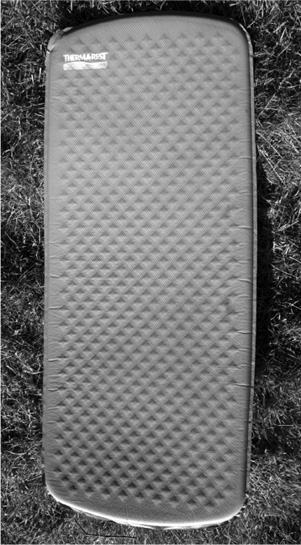

Bivy bags made from nonbreathable fabric are now rare. Sleep in one of these and you’ll get damp pretty quickly. Waterproof-breathable fabrics are much better, though some condensation is still possible in humid conditions. Gore-Tex is the standard fabric, though there are proprietary ones like Bibler’s ToddTex and Integral Designs’ Tegraltex as well as coated fabrics like Triplepoint (used by Exped). The extremely breathable eVENT fabric, which seems ideal for bivy bags (see pages 153–54) is starting to appear. Exped makes a 25-ounce eVENT bag. Highly breathable but not fully waterproof fabrics like Nextec’s EPIC are also used. These are less prone to condensation than waterproof fabrics and will keep off dew and light rain but not heavy rain. Most bivy bags have non-breathable, coated undersides. The idea is that your sleeping pad goes inside the bag and on top of the base, so there’s no point in making the bottom breathable. Some bags have straps inside to hold your pad in place. I prefer bags made wholly from waterproof-breathable fabric, however, since I like to put my pad under the bivy bag so the bag can move with me. I don’t want a nonbreathable layer above me, which can happen if I turn over with the bag while asleep or if I deliberately turn it over to put the leak-prone zipper under me, which is the best way to stay dry when it rains. Placing the pad under the bivy bag also protects the bag against abrasion and sharp stones and thorns. A bivy bag needs to be roomy enough to allow your sleeping bag to expand fully. If it compresses the sleeping bag, you’re likely to feel cold and uncomfortable. If the bag is too big, however, pockets of cold air can form where it doesn’t touch the sleeping bag, which is likely to lead to more condensation. All bags have hoods of some sort, closed with a zipper or drawcord and often backed by no-see-um netting—essential in bug season. The bigger bivy bags can hold some of your gear such as clothing. Weight depends on the fabric and the design but generally runs from 8 to 32 ounces.

Straight-across zippers or entrances closed by drawcords are adequate for occasional use and bags that will mostly be used as sleeping bag covers in shelters. More complex entrances with vertical, diagonal, or curved zippers that make getting in and out easier and allow you to sit up with the bag partly undone are worth considering only if you intend to bivouac regularly, since these features add weight and cost. Many models have bug netting behind the zippers so you don’t have to close the bag fully against biting insects. Hooped bivies keep the fabric off your face, but I find them claustrophobic because there’s so little room. I spent a night in one once, and that was enough. I prefer simple bags, which I close fully only in heavy rain, so my face is out in the air most of the time. If you need more space, a good nonclaustrophobic option is to combine a small tarp with a bivy bag. This isn’t as stable as a bivy bag with integral poles, but the setup can allow you room to cook under cover and doesn’t shut you into a tiny, dark space. Some people use a bivy bag under a full-sized tarp to protect their sleeping bags against any rain that might blow in.

Bivouac bags are light and convenient for places where pitching a tent might be difficult, such as in the lee of a boulder or under a spreading tree. However, while a good bivy bag will keep out rain and wind, you have to cook outside whatever the weather or the biting insects. Unless the night is calm, dry, and insect-free, I prefer to sleep in a tent or under a tarp and cook, eat, read, write, and contemplate the world in comfort. This doesn’t mean I never carry or use a bivy bag; there are situations, even when tent camping, when one comes in handy.

My first bivy bag was a 19-ounce Gore-Tex model with a horizontal zippered entrance covered by a flap. It once kept me and my down sleeping bag dry during several hours of heavy rain. That was many, many years ago, and that bag long ago started to leak. Because I don’t carry a bivy bag much anymore—I just sleep out in my sleeping bag and move into a shelter if the weather changes—I replaced it with a lighter-weight waterproof-breathable coated Pertex nylon bag, the Rab Survival Zone, which weighs just 8.5 ounces (though the current catalog weight is 12 ounces). The fabric is very thin and probably not that durable, but since I mostly carry it in winter as an emergency item and have slept in it on maybe a dozen occasions in eight years, it’ll last me a long while. I’ve also tried bags made from Tegraltex, ToddTex, and Sympatex. They all work much the same.

Even on calm, dry nights, condensation can be a problem with bivy bags. I once tested a bivy bag high on a bare mountainside on a clear and starry summer night. There was just a slight breeze, which I avoided by sleeping in a small hollow. By dawn, a thick, damp mist covered the ground. The outside of my bivy bag was wet, and there was a lot of condensation inside and on the outside of my sleeping bag. Turning the bivy bag inside out and draping it over a boulder along with the sleeping bag soon cleared the moisture as the mist faded and the sun rose. On colder nights I’ve awakened to find a layer of ice inside the bivy bag. Even if it doesn’t seem damp, it’s advisable to air your sleeping bag as soon as possible after a night in a bivy bag to get rid of any moisture it may have absorbed. Condensation is a reason for using bivy bags only on short trips or in mostly fine weather. It’s hard to keep your sleeping bag dry if the weather is damp for several days.

In winter I usually carry a bivy bag as a backup shelter and sometimes use it inside my tent or a snow shelter for extra warmth and to protect against dripping condensation. A bivy bag adds several degrees to the range of a sleeping bag.

Outdoor Research, Bibler, Exped, and Integral Designs all offer a range of bags in waterproof-breathable fabrics. I especially like the look of the Bibler Winter Bivy, made of EPIC and weighing just 9 ounces. Although not fully waterproof, this would be fine for use in tents and snow shelters and outside for dew and drizzle. Oware also makes an EPIC bivy bag, which has a silnylon base and weighs 10.5 ounces without bug netting and 12 ounces with it. Oware makes Gore-Tex bivy bags too, and there are many design options so you can customize your bag.

The most interesting bivy bag I’ve come across is the Hilleberg Bivanorak. This 18-ounce bag is made from waterproof-breathable coated ripstop nylon and has sleeves and a hood so you can keep your arms and head protected when you sit up in it. There’s a drawcord at the foot too, so you can open it up, stick your legs out, and wear it as a rain jacket. The Bivanorak is very roomy and will fit over a medium-size pack. The material does flap a little and breathability isn’t that good when walking. I wouldn’t want to walk far in it, but as an emergency item it’s excellent. I have used it at rest stops in stormy weather and enjoyed the extra protection. As a bivy bag it’s very roomy, easily big enough for a full-length mat and a bulky sleeping bag. However the fabric is quite thin and it’s awkward to sit up with a mat inside, which negates one of the advantages of the design, so I prefer to keep the mat outside. I haven’t used it in prolonged or heavy rain but the drawcord closures at the cuffs and foot and the hood opening mean it can’t be 100 percent waterproof, though I wouldn’t expect much leakage. The hood and sleeves can be tucked under the bag but the foot will always be exposed to the weather.

Carrying an emergency shelter on day hikes and side trips away from camp is a good idea, especially in winter or when you’re going above timberline. An expensive waterproof-breathable bivy bag is unnecessary for this purpose, however, as well as a little heavy. Nonbreathable plastic and foil bags, sometimes called survival bags, are fine for emergency use. They’re inexpensive and take up little room in the pack. The comfort isn’t great—I once slept out in a plastic bivy bag and got extremely damp—but if you ever need one, you’ll be grateful. For emergency shelter in summer I usually carry an MPI Space Brand Emergency Bag, made from polyester foil with an aluminum reflective surface. It weighs 2.5 ounces and measures 3 by 7 feet when unfolded. This is a very thin bag that will keep off the wind and rain but won’t provide much warmth by itself. The MPI Extreme Pro-Tech Bag has a sealed corrugated pattern of the same fabric that traps air and is meant to be much warmer. There are elastic fibers in the construction that allow the bag to hug the body, cutting out dead air space. It weighs 12 ounces. An alternative is a plastic survival bag like one from Coghlan’s that weighs 9 ounces. I’ve often carried one of these on day hikes.

The Hilleberg Bivanorak, a bivy bag that becomes a rain jacket.

Tarps almost disappeared as backcountry shelters during the last third of the twentieth century as hikers turned to the seductive attractions of curving flexible poles and smooth, taut nylon tents. In the previous edition I wrote that “constructing your own shelter from sheets of plastic or nylon and cord is something hardly any backpacker does these days.” Since then there’s been a big and somewhat astonishing resurgence in the popularity of tarps because of both the ultralight revolution and the use of trekking poles, which make good tarp supports, although most backpackers still use tents.

First, though, a definition. A tarp is a sheet of fabric that can be suspended from poles or trees to make a shelter. Once you add doors it becomes a tent, or at least a fly sheet. Such designs will be considered below under Tents. Here I’m talking about basic tarps only.

I first used a tarp as a cooking shelter in areas where the presence of bears made eating and cooking in or near my tent unwise and where the likelihood of rain meant that eating and cooking outside could be unpleasant. On long walks in both the Canadian Rockies and the Yukon, I carried an 8-by-9-foot silicone-coated ripstop nylon tarp, with grommets for attaching guylines along each side, to use as a kitchen shelter. On the many occasions when I made camp in cold, wet, windy weather, the protection it provided while I cooked and ate was welcome and certainly justified its 16 ounces of weight. I usually pitched it as a lean-to, slung between two trees on a length of cord. Occasionally I made more complex structures, using my staff plus fallen branches as makeshift poles. At sites with a picnic table, I found I could string the tarp above the table and create a sheltered sitting and eating area.

However, I’d never used a tarp in place of a tent on a long walk until I hiked the Arizona Trail in 2000, when the almost certain prospect of dry weather made a tent unnecessary. Since then I’ve used a tarp frequently, including on a 500-mile hike in the High Sierra, and it’s become my favorite shelter. I now reserve tents for dependably wet, windy, or buggy places.

Another use for a tarp is as an awning for your tent, which provides a large undercover cooking, storage, and drying area that also lets you leave your tent door open in rain with no danger of leakage. I drape the tarp over the tent door, peg out the sides, then use a trekking pole or poles to support the front.

The advantages of tarps are low cost, low weight, space, views, adaptability, good ventilation, and an element of creativity in how you pitch them. Cooking under a tarp is easy because there’s no sewn-in groundsheet and you can raise a corner or side for safety. With each side raised high, you have a 360-degree view yet are still protected from precipitation. With a tent you’re either inside it or outside.

The disadvantages are that tarps can be difficult to erect in storms, need careful pitching to keep out wind-driven rain, and—worst of all in my view—don’t keep out bugs. Condensation can occur, but it’s never the problem it can be in a tent: a breeze usually prevents it. If there’s no wind, then you can pitch the tarp to allow plenty of ventilation.

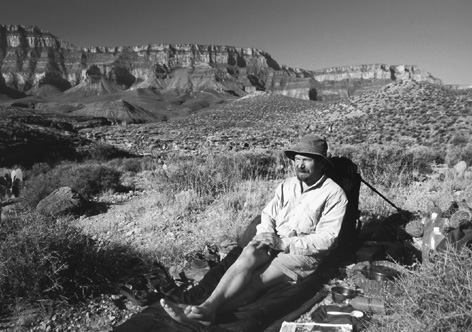

Tarp pitched as a lean-to.

Lightweight tarps, weighing 5 to 32 ounces, used to be hard to find but are now widely available. Companies like GoLite, Hilleberg, Bozeman Mountain Works, Integral Designs, MSR, Equinox, Campmor, Crazy Creek, and Oware offer a wide selection, as do some of the small specialist companies that have sprung up as part of the ultralight hiking movement, such as Lynne Whelden Gear, Dancing Light Gear, and Moon-bow Gear. Most tarps are made from silicone-coated nylon (see Tents below for fabric details), some from standard polyurethane-coated nylon. Sheets of plastic from building and hardware stores can be used as tarps, but they’re not very strong and can tear. Plastic is inexpensive, and some people leave torn sheets of it in the wilderness. I know; I’ve packed a few of them out. Disposable equipment isn’t environmentally friendly whether you pack it out or not, so overall I think it’s best not to use plastic for shelters.

Tarp pitched high off the ground for good headroom and ventilation. GoLite Cave.

Most tarps are flat sheets, though some have graceful shapes with curved sides—the MSR Moss HeptaWing (25 ounces) has seven sides; the Dana Design Hat tarp (24 ounces) has six and can also be zipped up to make a two-person bivy bag. The shaped tarps may be more wind-resistant, but they’re also heavier and more costly. Sizes vary enormously. For solo use, 5 feet by 8 feet is probably the smallest feasible size. I tried the 7-ounce 5-by-8-foot Integral Designs Siltarp and found it just big enough to protect me if I pitched it carefully. I prefer more space, however, and the tarp I use most measures 7 feet by 11 feet, big enough for two and roomy for me and my gear. It’s a silicone-nylon GoLite Cave 1, a Ray Jardine design. It weighs 14 ounces; stakes add another 4 to 6 ounces. The Cave has a small awning at each end, known as a “beak,” that gives greater protection against rain than open ends. The beaks can be pitched down to the ground to seal off the ends in severe storms. There are plenty of stake points and guylines, including some on the sides that can be tied to poles to create more interior space and prevent sagging. The larger Cave 2—8 feet, 9 inches by 11 feet, 7 inches and 18 ounces—sleeps two or three. There are two GoLite tarps with a beak at one end only: the Lair 1 (8 feet by 8 feet, 8 inches, 12 ounces) and Lair 2 (8 feet by 11 feet, 4 inches, 16 ounces).

Clockwise from top left: A lean-to tarp; an open-ended ridge using trees; an open-ended ridge using two sticks or poles; and an open-ended ridge using four sticks or poles.

I don’t use a tarp in bug season because I haven’t yet found any netting that I’m happy with. I want to be able to sit up and move around under a tarp, not feel trapped in a mesh enclosure. Once a tarp gives less space and freedom than a tent, I’d rather have a tent. If bugs are out only when you’re sleeping, you could just drape a piece of no-see-um material over your head or the hood of your sleeping bag. That doesn’t solve the problem of bugs in the evening and morning, however. GoLite has a new bug tent that could be the answer. It comes in two sizes, the solo Lair 1 Nest with a front height of 33 inches (21 ounces) and the two-person Lair 2 Nest with a front height of 45 inches (25 ounces), and will fit inside the Lair and Cave tarps. The Nests have zipped doors and polyurethane-coated nylon floors and look far better than the original Nest, which didn’t have a zipped door; you had to crawl in under a flap, an awkward maneuver that brought in insects too.

Tarp with bug-netting inner. GoLite Cave and Nest.

Tarp pitched as a pyramid with a single pole.

Some tarps have mesh panels at the ends and mesh strips around the perimeter. These probably help, but my experience is that when biting insects swarm, you need a totally closed, insect-proof shelter to keep them out. When the bugs are bad, I like a down-to-the-ground fly sheet with a zippered door and a vestibule where I can burn a mosquito coil or insect-repellent candle and an inner tent with mesh doors.

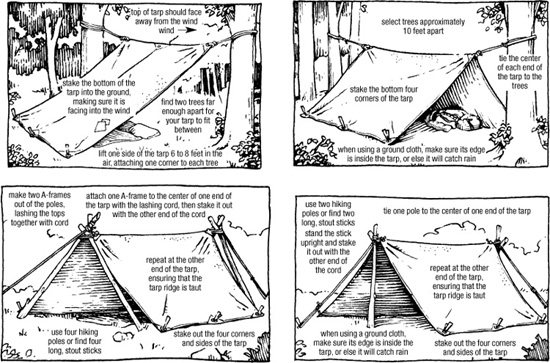

Tarps can be pitched in so many ways that the best advice is to experiment and practice—you don’t want to be trying to figure out how to erect a stormproof shelter in the rain at the end of a long day’s hike. Try different shapes and profiles. If you have a trekking pole or poles, these can be used as supports. You can easily lower the profile of the tarp if the weather becomes stormy by shortening the poles and then restaking the tarp from inside. You can also fit poles inside a tarp and pull the fabric over the handles without danger of damaging the tarp, as can happen with a stick. Having supports inside adds to wind resistance and stability. If you don’t have poles, you’ll need to find a stout stick or two or else tie the tarp to trees, which means camping only below timberline. You could carry tent poles, but this adds weight. You need enough stakes to hold the tarp down plus some cord for guylines unless your tarp comes with guylines attached. Most tarps have grommets or loops for attaching guylines. If yours doesn’t or you want extra stake points, you can wrap a smooth stone in the fabric and tie a loop of cord around the neck between the stone and the rest of the tarp. I’ve always found this method satisfactory, but there’s a device called the Grip Clip, from Shelter Systems, that does the same job with perhaps less likelihood of tearing the fabric. Grip Clips come in various sizes; the smallest 0.08-ounce Micro and the 0.2-ounce Light Fabric clips are recommended for lightweight tarps. For silicone nylon, Shelter Systems recommends fitting pieces of a balloon as gaskets because the fabric is so slippery. To use Grip Clips, you push the two open-centered halves together with the tarp fabric between them. The pieces snap together and cannot come undone. Guylines can be attached to the clips, and they come with 11 inches of cord attached.

Tarp pitched as a low-profile ridge with a storm approaching. GoLite Cave.

Tarp pitched as a pyramid with a trekking pole. A second pole is being used to hold the front of the tarp open.

The most common tarp shapes are the lean-to, the ridge, and the pyramid. For the first, tie the corners at each end of a long side of the tarp to trees or poles, several feet above the ground. If you use poles, they’ll need guying out to keep them from falling over. The other side of the tarp can be staked to the ground or, for better ventilation if there’s no wind, loops of cord can be attached to the stake points and the tarp can be pitched with an air gap between the lower edge and the ground. Lean-tos are roomy and reasonably condensation-free, but they protect you on only one side, and they can flap in the wind.

Tarps can be pitched in unusual shapes using trees, both standing and fallen, as supports. GoLite Cave.

Ridges give more protection. An open-ended ridge can be pitched by attaching lines to the centers of the short sides of the tarp and tying them to trees or trekking poles. Again, you’ll need guylines to stake the poles out. If it’s windy, one end of the ridge can be staked down close to the ground, which is most easily done with a tarp with a shaped end like the GoLite beak. This produces a sloping ridge that is more wind and rain resistant than one with both ends at the same height.

For a pyramid, stake out one side, then pull the center of the tarp over the handle of an upright trekking pole and tie it off with a bit of cord before staking out the other two corners with the tarp slack between them to leave space for a door. The center of this loose side can be pulled taut with a guyline or, more effectively, by tying it to a pole. Pyramids are quite wind resistant but are best suited to large tarps. Small tarps may not give you enough room to lie down.

These three basic shapes can be varied according to terrain and available supports. I’ve tied tarps to fallen trees to make unusual shapes and fitted them into awkward spots with one corner at ground level and the one diagonally opposite high in the air. Experiment. That’s one of the joys of tarp camping.

With any shape, a low profile with the edges of the tarp at ground level is the most storm resistant but also the most prone to condensation.

A groundsheet, or ground cloth, is useful when sleeping under the stars or under a tarp, especially if the ground is wet. I also carry a groundsheet if I’m planning on using a snow shelter or wilderness huts or lean-tos, because their floors may be wet and muddy. Unlike many people, I don’t use one under my tent. I find tent groundsheets durable—I have some that have had more than a year’s use and are still waterproof—and I don’t want to carry the extra weight.

Cheap plastic sheets are lightweight but don’t last long, and they can’t be staked out, which is necessary when it’s windy. Nylon groundsheets are much better, especially those that come with grommets or stake points. Tent-footprint ground-sheets, designed to be used under tents, work well and weigh 8 ounces or more, depending on size. Many tent makers offer them. Silicone nylon makes for a very light, strong groundsheet, though it can be a little slippery. I have one that measures 54 inches by 84 inches and weighs 8 ounces. Dancing Light Gear makes a sheet 72 inches long that tapers from 36 to 22 inches and weighs 4.5 ounces. GoLite’s Ultra-Lite measures 42 inches by 90 inches and weighs 5 ounces. The lightest ground cloths come from Gossamer Gear. The Spinnsheet, made from spinnaker ripstop nylon, comes in two sizes: the 27-by-84-inch size weighs 1.7 ounces; the 54-by-84-inch size weighs 3.4 ounces.

Of course, tarps can be used as groundsheets—and vice versa. I once used a groundsheet as a tarp during a thunderstorm in Yellowstone National Park. I didn’t want to cook in my tent because of bears, nor did I want to sit outside in the cold storm. So I slung my groundsheet, carried for when I slept under the stars, between two trees as a lean-to and used my pack as a seat while I cooked, ate, and watched the lightning flashes illuminate the forest and the rain bounce off the sodden earth.

An alternative to coated nylon is polyethylene, which comes in two forms, DuPont’s Tyvek and Space Brand aluminized fabric, and is much more durable than ordinary plastic. Tyvek is used in the construction industry and can be bought in rolls and cut to size (it’s also used for waterproof maps). Tyvek is very light and has become popular with ultralight hikers. Six Moon Designs sells Tyvek in lengths of 3 feet or more (84 inches wide, 1.6 ounces per square yard; 59 inches wide, 1.75 ounces per square yard for aluminized Tyvek). Lynne Whelden Gear sells ready-cut Tyvek groundsheets measuring 42 inches by 90 inches and weighing 5.5 ounces with a foot pocket in the end for your sleeping bag to protect it from rain blowing in at the end of a tarp. I haven’t used Tyvek, but it’s recommended by many experienced long-distance hikers. I have used MPI Outdoors’ Space Brand All Weather Blanket. Current versions are made from a four-ply laminate of clear polyethylene film, aluminum coating, reinforcing fabric, and colored polyethylene film. The blanket measures 60 inches by 84 inches and weighs 10 ounces. One side is silver, the other is blue, red, or olive. With the silver side out, these blankets make good sunshades in the desert. One drawback is that if you fold them for carrying, they tend to crack and then leak at the creases. I now roll mine, and this does seem to prolong the life. I don’t use it much anymore anyway, preferring lighter-weight silicone nylon.

A good tent provides complete protection from the weather and insects and also space to sit, cook, eat, read, make notes, sort gear, play cards, and watch the world outside. A tarp provides more space ounce-for-ounce, of course, but it doesn’t give the same protection against windy weather or, especially, biting insects.

Choosing a tent can be confusing. They come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, and few stores have the space to display many. There are limited opportunities to see tents pitched and to crawl in and out of them to assess how well they suit your needs. However, a good store should be prepared to erect a tent you’re considering buying so you can have a look at it.

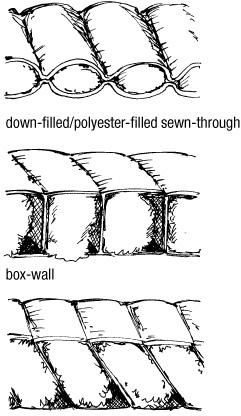

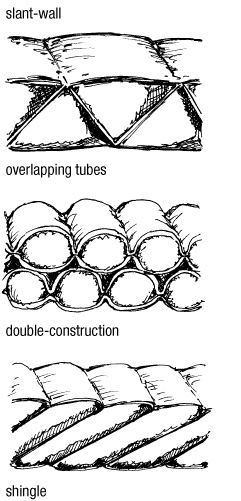

A tent’s primary purpose is to keep out rain and snow. Luckily that’s easy to do. Ideally, a tent should also let out moisture vapor. This is not so easy. Bodies give off a fair amount of vapor, and there may be more from wet clothes, cooking, steaming drinks, wet hair, drips, and spills. Moisture from damp ground and vegetation in the vestibule and around the edges of the fly sheet can also condense on cold, impermeable tent walls. If you brush against those walls, you’ll get damp too. In my experience the standard two-skin (or double-skin or double-wall) tent design with a breathable, nonwaterproof tent (nowadays sometimes called a canopy) and a nonbreathable, waterproof fly sheet or rainfly is the best solution to condensation, but it’s nowhere near perfect. In theory, moisture passes through the inner fabric and is then carried away by the air circulating between the two layers. Any condensation that forms on the fly sheet can run down to the ground, with stray drips repelled by the inner wall. To prevent condensation from reaching the inner tent, the gap between the tent and the fly sheet must be large enough that wind cannot push the two together. And you need to be careful not to press the inner walls against the fly sheet.

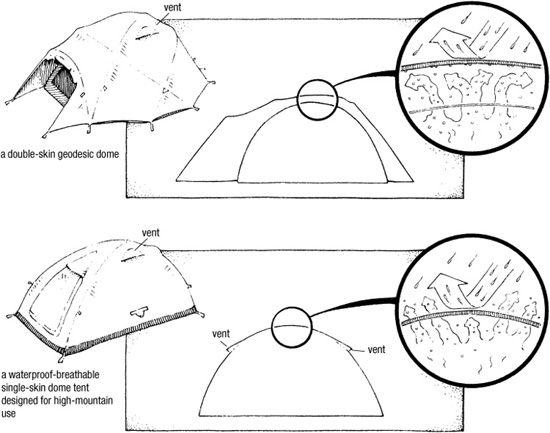

Double-skin and waterproof-breathable single-skin tents.

To some extent the double-layer system works. However, moist air is carried away only if there is a breeze and if it can escape. Since warm air rises and warm air holds more moisture than cold air, a vent high up on the fly sheet can create a chimney effect, drawing cool, dry air in under the bottom edge and expelling warm, damp air through the vent. Vents are more common than they used to be, but many tents still don’t have them.

Two-way fly sheet door zippers are also useful for ventilation. I leave at least the top few inches open unless rain starts coming in through the gap.

Condensation is worst in calm, humid conditions. Then nothing—not even leaving all the doors open—will prevent the fly sheet from becoming very wet. One misty night I was awakened by drips falling from the tarp I was under, which was pitched as a lean-to. In a much more enclosed tent, condensation is unavoidable. I have even left tents empty in calm, humid conditions and found the fly sheets wet with condensation in the morning.

Where bugs are a problem, I’ve sometimes felt my tent turning into a sauna while I cooked inside the vestibule with all the doors shut tight, producing clouds of steam that promptly condensed on the fly sheet. But being warm and damp is preferable to being eaten alive!

Condensation is a more serious problem in freezing temperatures, when the inner tent can become so cold that moisture condenses on it and then drips back on the sleeper below. If temperatures drop even more, the problem may be solved, because the moisture will freeze on the tent. But when you wake in the morning and start to move around creating heat, the ice will melt, and it can seem as though it’s snowing inside the tent. Ventilation is a partial answer to this.

If you camp regularly in damp, humid climates—on the Olympic Peninsula or in the Maine woods, say—it’s worth looking for a tent with plenty of ventilation options, such as hoods over door zippers and covered vents. Tents that have sloping inner doors or large mesh panels without covers are poor designs for humid areas. Condensation can drip through the open door or the mesh panels and onto the groundsheet or your sleeping bag. The best design for keeping condensation out of the tent has solid inner walls, a vertical door, vents at the high point of the fly sheet, and outer doors with two-way zippers. Any mesh panels should have covers.

Polyester and nylon are excellent fabrics for backpacking tents, being strong, light, quick drying, and durable. Canvas, the traditional tent material, is not strong enough to make lightweight tents. Polyester stretches less than nylon when wet and resists ultraviolet light better. (Whatever the fabric, it’s still best not to leave tents up for long in bright sunlight.) However, nylon has a much higher tear strength weight-for-weight.

Inner tents are usually made from nonwater-proof-breathable nylon that absorbs little moisture, dries quickly, and allows moisture vapor through. Most have a light fluorocarbon finish to repel drips of condensation from the fly sheet. Tents designed for warm weather often have large mesh panels for ventilation to keep out insects and provide views of the stars when the fly sheet isn’t in use. However, mesh can let in cold breezes and drips of condensation. Some tents have mesh panels with covers for cool and damp conditions. In my experience, while mesh panels do make a tent cooler, they don’t decrease condensation.

Seam sealant for silnylon.

Fly sheets may be coated with polyurethane or impregnated with silicone. Silicone nylon, often abbreviated to silnylon, is the lightest fabric yet has a much higher tear strength than polyurethane-coated fabrics. It also has the best resistance to ultraviolet light. Silicone encapsulates the fibers completely rather than just lying on the surface, so it can’t wear or peel off, making it very durable and permanently water repellent. Even after years of use, rain still beads up on silnylon, so it dries very quickly. Polyurethane is applied to only one side of a fabric; it’s put on the inside of the fly sheet to protect the coating from wear. Once the original durable water-repellent treatment (DWR) wears off, the outside can absorb moisture, making it heavy and slow to dry. Some fly sheets are coated inside and out with silicone, while others have silicone on the outside but polyurethane on the inside so the seams can be taped.

Weights for tough inner and outer nylons are about 1 to 2 ounces per square yard (usually stated in the form 1.5-ounce nylon); the lighter ones need slightly more care than the heavier materials. Deniers (see page 117) range from 30 to 75. To prevent leaks, fly sheet seams may need sealing with a seam sealant like SeamGrip unless they come with taped seams. Neither tapes nor standard sealant will stick to silnylon. You’ll need McNett’s special silicone sealant, SilNet. That said, I’ve been using silnylon tents and tarps for well over a decade, including months at a time in wet climates, and I’ve never sealed any seams or had any leaks.

An intriguing alternative to the breathable tent–waterproof fly sheet norm comes from Stephenson’s Warmlite, whose tents have two layers made of coated fabric that are permanently linked. The inner layer also has an aluminized coating on the inside to block radiant heat. There are low and high vents to create a chimney effect. This design minimizes condensation, according to the makers, because the inner tent is warmer than in standard designs. I haven’t tried a Warmlite tent, but it makes theoretical sense and has gotten positive reviews. Friends who have one speak highly of it. For more on Warmlite tents, see page 209.

Some tents now come with plastic windows in the doors or the roof so you can look out without opening the tent—at least in theory. In my experience these mist up with condensation very quickly or else are covered with rain and are actually only useful at those times when opening the door isn’t a problem. These windows used to be found only in budget tents, since they were brittle and cracked easily. Now they are made from flexible and tough materials and are more widespread.

Tents made from waterproof-breathable fabrics are easy to pitch and quite light for their size because they have a single skin. Wind can’t get in under the edge of the fly sheet because there isn’t one, so they can be warmer than two-layer tents. The chief makers of these tents are Bibler and Integral Designs, each using its own proprietary fabrics, ToddTex and Tegraltex, respectively. Gore-Tex tents seem to have mostly disappeared.

Waterproof-breathable tents work well in dry conditions, but they aren’t breathable enough to cope with much moisture vapor in humid conditions, and then condensation is likely; moreover, the condensation can’t escape by running into the ground because there is a sewn-in groundsheet (see sidebar, opposite).

My first true backpacking tent was a single-skin (or single-wall) nonbreathable coated nylon ridge tent. It was lightweight, easy to pitch, waterproof, and low in bulk when packed. However, in wet or humid conditions, to call the condensation copious was an understatement. It ran down the walls and slowly flooded the groundsheet. I replaced that tent with a double-layer model as soon as I could and wasn’t surprised when single-skin tents disappeared shortly afterward. The lightweight revolution has seen them reappear, on the basis that cutting out the inner tent and sewing the groundsheet to the fly sheet saves weight. These modern nonbreathable tents often have vents and door configurations said to reduce condensation. These might help a little, but the inside of a fly sheet in a double-layer tent can be soaked with condensation in humid weather even with vents and doors open and an air gap right around the perimeter, so there’s no way a single-skin tent, without that lower air gap, will have less condensation. I’d be very wary of nonbreathable single-skin tents with sewn-in groundsheets unless I camped only in places with low humidity. And then I would probably just carry a tarp anyway. A brief trial with the single-skin silnylon GoLite Den 2 (3 pounds, 9 ounces) showed that a good design with vents at each end does help, but when there’s no wind much condensation still forms. GoLite says the Den is for “areas with low humidity and/or with ample breezes.” I’d say this applies to all tents of this type, and I’d drop the or.

Low-profile, single-skin bivy tent of waterproof-breathable fabric. Bibler Tripod.

Low-profile single-skin tunnel tent of waterproof-breathable fabric with vestibule and trekking poles used to pull out the sides for more space inside.

Single-skin waterproof-nonbreathable tunnel tent. GoLite Den 2.

There are also single-skin tents without ground sheets, basically just fly sheets. These are still prone to condensation, but it can run into the ground rather than onto the groundsheet, so they’re more practical for conditions where a tent is most needed. Most pyramid tents are floorless single-skin models, as are many of the new ridge designs. The key when using these tents is to avoid touching the walls when they’re damp.

Tent floors are usually made from 2- to 4-ounce polyurethane-coated nylon. Long ago nylon floors didn’t stay waterproof very long and ripped easily, so people usually used a groundsheet under them, a habit that has remained even though the nylons used today are tough enough to make a ground-sheet unnecessary. The tent I used on my Canadian Rockies walk back in 1988 was still waterproof after eighty nights with no protection under it.

The best floors are the “bathtub” type with no ground-level seams. Short sidewalls keep out rain splashes that come under the fly sheet. Tiny punctures are the most likely damage to occur to floors. To prevent further leaks, cover them with spots of sticky nylon tape. Better yet, check the ground for sharp twigs and stones before pitching the tent to minimize the chances of puncturing the floor.

If you do use a groundsheet with your tent, make sure it doesn’t extend beyond the edge of the fly sheet, or rain can collect between it and the tent floor. This can happen even when it’s tucked well under the tent, though it’s much less likely if you fold up the edges of the groundsheet. On the few occasions when I’ve used a groundsheet with a tent, I’ve put it inside the tent.

Most tent poles are made from flexible aluminum, though those on less expensive models may be made from fiberglass. Pyramid tents often come with rigid aluminum poles. I’ve never used a tent with fiberglass poles, but the general view is that they’re not as strong as aluminum. Aluminum comes in different types; DAC Featherlite and Easton 7075 are regarded as the highest quality. The diameter of the tubing also affects the strength. Most backpacking tents have 8.5- to 9.5-millimeter poles. Tents designed for severe high-mountain weather may have thicker poles, such as 11.5 millimeters.

Carbon fiber is stronger, lighter, and more expensive than aluminum. A new pole material is Easton’s Ultralite A/C, carbon fiber bonded to an aluminum core. The poles are 30 percent lighter than standard Easton poles and are used by Sierra Designs. If you want to save a few ounces, you can—for a price—buy carbon-fiber poles for your tent from Fibraplex. These are half the weight of Easton 7075 poles. The pole on my favorite solo tent weighs 5.5 ounces. Since the shock cord linking the sections would weigh the same, I’d save maybe 2 ounces if I changed to carbon fiber. Of course, with a large geodesic dome tent with four or five long poles, the weight saving would be more significant, as would the increased cost.

Some flexible poles come prebent. If they are not prebent, they often develop a curve with use. This is not a problem as long as you don’t try to straighten them, because then they may break. Pole sections are normally linked by shock cord, which makes it easy to put them together and almost impossible to lose sections (though I managed it once after a shock cord snapped).

Poles may run through nylon or mesh sleeves or attach to the tent with clips or shock cord; some have flexible hubs at pole intersections. Pole ends fit into grommets, plastic pole cups, or webbing. Clips theoretically allow better airflow between the inner layer and the fly sheet than sleeves, but I don’t think they make much difference. What’s more important is that poles are marked so you know where each one should go. Many poles come already marked. If not, it’s worth sticking different-colored tape on each one.

Poles are strong when the tent is pitched but vulnerable when lying on the ground—especially long, thin, flexible poles. Take care not to step on them. And don’t use them as handholds when entering and leaving the tent. A companion once broke a flexible pole by putting all his weight on it as he left the tent during a winter gale in a remote mountain area. I had to scramble out of my sleeping bag, throw on some clothes, and repair it before the storm caused any more damage. I fixed it by slipping a short alloy sleeve over the break and binding it in place with duct tape. Such sleeves are supplied with most flexible-pole tents. I always carry one, though that’s the only time I’ve used it.

After I’d been using trekking poles for a few years it occurred to me that carrying tent poles as well was a little superfluous, especially since trekking poles are stronger than most tent poles. However, you can’t pitch a flexible-pole tent with trekking poles. Now, though, tents designed to be used with trekking poles are appearing, which makes good sense. I use mine with tarps and the GoLite Hex 3 pyramid tent.

Every tent must be staked to hold it down in wind. Fifteen to twenty stake points are plenty; more increase the weight you’re carrying and the time it takes to pitch the tent. Many tents need only eight to twelve stakes. Most stakes are made of steel or aluminum (I’ve found plastic too fragile for wilderness use), and they come in a variety of shapes. Thin ones work best in hard ground, wide-angled or curved ones in soft ground. For sand or soft snow, you need really wide snow pegs. I have a set of 12-inch hardened aluminum stakes for snow camping. They weigh 1.8 ounces each and are drilled with holes to save weight and to attach guylines so they can be buried horizontally for maximum holding power. Hilleberg, MSR, and SMC make snow stakes. Hilleberg’s come with a line and a hook for attaching them to guylines or stake points. Much lighter are fabric “stakes” with short lengths of cord attached that you fill with sand or snow and then bury, such as Bibler’s 1-ounce Soft Stakes and Exped’s 0.6-ounce Snow and Sand Anchors. I suspect it would be easy to make your own version of these.

A selection of tent stakes. From left: plastic I-beam for soft ground, C-curve for soft ground, short pin with loop end for hard ground, Y shape for soft ground, long pin with hook end for hard ground, thick pin for hard ground, snow stake for sand and snow.

Outside of snow country, I use 7-inch hardened aluminum pins (0.33 ounce each), which hold in most soils. For softer ground, I carry two or three 6-inch hardened aluminum V-angle stakes (0.5 ounce each). Y-shaped stakes are considered the strongest alloy ones, though I don’t like them because they are harsh on the hands. If you want very strong stakes that weigh very little, you can get titanium stakes, both pins and angles—at a price—from Stanley Alpine, Snow Peak, Vargo Outdoors, Bozeman Mountain Works (which paints them bright orange), and Simon Metals. Titanium pins are very thin and apparently can be driven into hard, rocky soil without bending or breaking. However, reports suggest that the thinness means they pull out of anything less hard too easily. Although I occasionally bend stakes, I’ve never felt the need for stronger ones. If you regularly camp on rocky ground or hardened tent platforms, titanium stakes might be worth using. In hard ground stakes can be tapped in with a small rock or pushed gently with the sole of your boot. Don’t hit them too hard though, or they might bend or break. If stakes are hard to pull out by hand, use another stake by hooking it into the end of the stuck stake and using it as a lever.

Stakes are easy to misplace, so I carry a couple of extras. However, on many occasions I’ve finished a hike with more stakes than I started with, finding ones others had lost. I keep stakes in the small nylon stuff sack supplied with most tents and carry them in a pack pocket so they’re easy to find when I pitch the tent.

Depending on the design, tents need anything from two to a dozen or more guylines to keep them taut and stable in a wind, though more than ten is too many for one- and two-person tents. Most tents come supplied with a full set of guys, but some have only the main ones plus attachment points for others. It pays to attach these extra guylines before they’re needed or at least carry some cord with you. I’d rather have plenty of guylines and leave them tied back when it’s calm than not have enough.

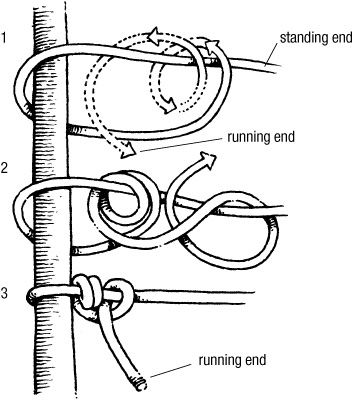

To avoid confusion and to help when sorting out tangles, different-colored guylines are useful, especially when several are attached to the tent at the same point. If the guylines are tied back in loops when you pack your tent, they’re less likely to tangle. I always try to do this, though when packing in a hurry during a storm, I often forget and end up cursing myself the next night as my numb fingers undo knots. Metal locking or plastic friction adjusters come with most guylines, but you can also buy them separately. It’s useful to know how to tie the tautline hitch (see illustration) in case you need extra guylines and have no extra mechanical sliders. This knot will slide up and down the guyline when the line is slack but lock when it’s tightened. Nylon stretches when wet, so guylines should be staked out tightly. If it’s wet and windy, I generally retighten them before going to sleep.

Tautline hitch. Wrap the rope around an object to create a loop. Feed the running end of the rope over the standing end and through the loop at least twice (1). Bring the running end out of the loop and over the standing end. Secure the running end as shown (2). Tighten the wraps so they lie flat and close together (3).

The weight of a tent depends on its size and the materials it’s made from. Tents come in a wide range of sizes—from tiny bivy tents barely big enough for one person to monsters that will accommodate half a dozen Himalayan mountaineers and all their gear. At a minimum, you need enough space to lie down and stretch out without pushing against the walls or either end. This is all the space the smallest tents have. There’s no room to sit out a storm in comfort (for which you need enough headroom to sit up), nor space to lay out gear inside, nor a vestibule big enough for safe cooking. They are light, though. Most of these tiny tents are designed for one occupant. The amount of space two people need depends on how cramped they’re prepared to be and how friendly they are. Many tents described in catalogs as sleeping two assume very close friendships!

Most tent makers give the floor areas of their tents, as do some retailers, and they all give length and width so you can compare sizes. As a rough guide, I’d look for at least 30 square feet of floor area in a three-season tent for two (excluding the vestibule), and 35 square feet or more in a winter tent. For solo use, 18 to 20 square feet is enough. The width for two should be at least 54 inches at the widest point; for one, 36 inches will suffice. Length should be at least 7 to 8 feet. Backpackers over 6 feet tall need to consider the length of a tent carefully; in many tents, they’ll find their feet pushing against the end.

In mostly dry areas where storms are unlikely and you just want a bedroom to keep out bugs or the occasional shower, the smallest, lightest tents may be fine. In wet areas or in winter, you need more room because you’re likely to spend more time in your tent and in winter you’ll have bulkier sleeping bags and clothing.

Being able to sit up in a tent makes a huge difference to how spacious it feels. I don’t like tents, however lightweight, that don’t let me sit up, because they make me feel uncomfortably confined. The key factor here is the distance between the floor and the top of your head when you’re sitting cross-legged. If you measure that, you can determine from catalogs which tents will be roomy and which will give you a crick in the neck. I always look for a tent with at least 35 inches maximum inner height.

The size of vestibule you need depends on whether you intend to cook and store gear in it. For cooking, a vestibule must be high enough and wide enough to prevent the fabric from catching fire or melting. Tents for two sometimes have double vestibules, and although they’re heavier, they make tent living much easier. For areas where you usually live outside and use the tent only for sleeping, vestibules don’t need to be large. Indeed, it doesn’t matter if there isn’t one at all.

I like vestibules with large zippered door flaps that can be rolled out of the way. It’s not quite the same as bivouacking, but having a wide-ranging view is far better than being encased in a nylon cocoon. I close the doors only if forced by the weather or bugs.

Many tents weigh more than they need to, as designers add excess features and “improvements.” It’s easy to be impressed by fancy designs. I know; I’ve done it. I started out using solo tents in the 4- to 4.5-pound range (weights include stakes and stuff sacks—the actual weight when carried), but a decade later my tents weighed 5 to 6 pounds. Wanting to cut that weight, I decided on 4.5 pounds as the maximum I would carry in the future. With the latest materials, that has come down to 4 pounds. Except when I’m testing heavier tents for review, I’ve stuck to that rule. Keeping the weight down when you share a tent is easier. I’ve used a 5.5-pound tent for snow camping with two and not felt cramped, and there are plenty in the 5- to 8-pound range that provide ample room.

Tent makers usually list two weights for tents. The minimum weight covers just the tent, fly sheet, and poles. The packed weight includes stakes, stuff sacks, spare parts, and instructions. The weight you’ll carry is likely to be closer to the packed weight than the minimum.

The stability of your tent becomes a matter of great concern once you’ve struggled alone in the dark, cramming gear into a pack under a thrashing sheet of nylon after the wind has snapped one of your tent poles—which happened to me many years ago. It was pouring rain and I had to make a long night descent to the trailhead. Had it been a more remote location in winter, I could have been in serious trouble.

In the distant past, three tents collapsed on me—two because of wind and one because of a heavy, wet snowfall. On two other occasions I’ve camped with others whose tents have been blown down. I’ve also slept peacefully in a well-designed, properly pitched tent during a gale that blew down less stable tents nearby and shook others so hard that the occupants got little sleep. If you spend the night expecting your thrashing tent to collapse any minute, you’ll be too exhausted to enjoy the next day.

The importance of tent stability depends on where and when you use your tent. For three-season, below-timberline forest camping, it’s not a major concern. For high-level, exposed sites and winter mountain camping, it’s very important.

Tent design and materials both contribute to stability. The most stable designs don’t have large areas of unsupported material that can catch the wind. Many makers describe their tents as three-or four-season models. However many three-season tents are as stable as four-season ones. What they lack is often snow-shedding ability, extra space, and large vestibules. High winds can occur above timberline and in exposed areas at any time of year anyway.

Stability is relative. Hurricanes that strip roofs off buildings and blow down trees can certainly shred even the strongest four-season mountain tent. In strong winds, your experience and ability to select a sheltered site are as important as the tent you have. If pitching the tent in a storm seems impossible, it’s better to go on, even after dark, in search of a more sheltered spot. You’ll rarely have to camp in storm-force winds, but if you do, seek out whatever windbreaks you can—piles of stones or banks of vegetation—and consider sleeping out in a bivy bag, if you are carrying one, or even wrapped up in your tent. It may be uncomfortable, but it beats having your tent destroyed in the middle of the night.

Careful pitching is important, too. A taut tent with no loose folds of material will resist wind much better than a saggy mass of nylon. The best mountain tents will still thrash around in a storm if badly pitched. When pitched properly, a stable tent should feel fairly rigid when you push against the poles.

Traditionally the fly sheet was an extra layer thrown over the tent to protect it from rain. Originally both layers were needed to keep rain out, since neither was fully waterproof. When nonbreathable coated nylon was introduced for fly sheets, it made sense for inner tents to be breathable rather than water resistant. This can present a problem when you pitch the tent in the rain. Unless you pitch it very fast, which depends on both your skill and the design, it can get very wet. To counter this, some tent makers—mostly in wet Northern European countries—began building tents that pitched fly sheet first. Since the poles are often on the outside, these are sometimes known as exoskeleton tents. Many of them also pitch as a unit; that is, the fly sheet and inner tent go up together. If the fly sheet is damp inside with condensation, you can then detach the inner tent when packing up so it doesn’t get wet from being packed with the fly. With many inner-first-pitching tents you can now pitch the fly sheet separately if you want, often with a separate groundsheet. You can’t usually then add the inner tent, though.

For very wet areas where having to pitch in the rain is likely, I prefer exoskeleton tents. For drier areas either design will do, while for very dry areas inner-first pitching is probably best, since you may not need the fly at all much of the time. But in those areas, why do you need a tent at all?

Dark tents can be gloomy inside in dull weather. Pale tents let in much more light. Warm colors—red, orange, yellow—give a warm light, which can be psychologically appealing in cold weather. Gray, blue, and green feel cooler; maybe too cool in dull weather but pleasant when it’s hot. In most environments bright, hot colors stand out and can be an eyesore. At high latitudes where it barely gets dark during the summer, dark tents can be soothing and more conducive to sleep. Overall I prefer inconspicuous greens, browns, and grays for fly sheets (and tarps) but a warm color such as yellow for inner tents. That’s except for snow camping, when I like bright yellow or orange tents. Any colors other than shades of white and pale gray look black at a distance against snow anyway, so the problem of visual pollution doesn’t apply in the same way.

Since the advent of curved poles in the early 1970s, designers have created a bewildering array of tent shapes, some of them bizarre. Overall, though, these developments have led to a superb range of tents that are lighter, roomier, tougher, and more durable than ever before. Some tents are hard to classify, but most fit into the categories of ridge, pyramid, dome, tunnel, and single-hoop.

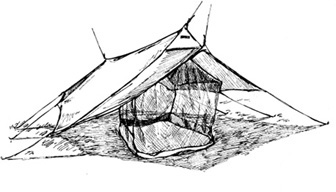

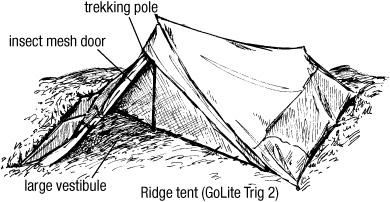

Before flexible poles appeared, most tent designs were variations on the standard ridge tent, a solid structure that has had a bit of a renaissance as hikers have discovered that trekking poles make good upright tent poles. The simplest, but the least stable and most awkward to use, are those with upright poles at each end. A-poles make a far more stable tent, known as an A-frame, and leave entrances clear. It’s not easy to use trekking poles as A-poles, though. Ridge tents don’t have good space-to-weight ratios, and the angled walls mean a lack of headroom compared with curved pole designs. However if you use trekking poles, then ridge tents that can be erected with them are worth considering. These are usually single-skin tents, often with a bug netting inner tent as an option. The only one of these tents I’ve tried, albeit briefly, is the silnylon GoLite Trig 2. This has a sewn-in floor, a large vestibule, and retractable flaps. Mesh panels along the base of the sides and the internal mesh door keep out insects and provide ventilation. It weighs 2 pounds, 15 ounces without stakes, which add another 3 to 6 ounces depending on the type. Its area is 33 square feet plus 13 square feet in the vestibule. There’s a smaller version, the Trig 1, that weighs 2 pounds, 3 ounces, and has an area of 24 square feet plus 5 feet in the vestibule. The Trig is easy to pitch with two trekking poles, is fairly roomy, and quite stable. I like the look of it but I need to try it in really wet weather to see what the condensation is like. The polyester MSR Trekker Tarp (4 pounds) with optional mesh 40-square-foot Trekker Tarp Inner (2 pounds) sleeps two and can be used as a two-door tent or a three-sided tarp. Lighter is the side-opening MSR Missing Link at 3 pounds. This has a sewn-in groundsheet and a total area of 51 square feet. Much lighter again at 1 pound, 3 ounces is the 34.7-square-foot silnylon Black Diamond Beta Light. An optional floor weighs 1 pound, 5 ounces, and a mesh inner tent, the Beta Bug, weighs 1 pound, 14 ounces. Other ridge tents that can be pitched using trekking poles are sold by Dana Design, Oware, and Lynne Whelden Gear. There are also slightly modified tapered ridge tents that have a small hoop at the rear and a single pole at the front, available from Six Moon Designs and Henry Shires’ Tarptents—the latter come with optional Tyvek groundsheets or sewn-in groundsheets. Transverse ridge tents, where the ridge runs across rather than along the tent, are sold by Dancing Light Gear and Dana Design. The 40-square-foot silnylon Dancing Light Tacoma-for-2 Shelter looks interesting. It weighs 2 pounds, 6 ounces and has Velcro closures rather than zippers on the doors, a sewn-in groundsheet, and doors on each side. Dana Design’s Javelina tapers sharply to one end, has an area of 31 square feet, and weighs 3 pounds, 5 ounces.

Basic tent designs.

A single-skin ridge tent pitched using trekking poles. GoLite Trig 2.

Tarp pitched as a tapered ridge to keep off the wind at a cool, breezy timberline camp. GoLite Cave.

There are few tents left with A-poles, though this is a stable, easy-to-pitch design that is less expensive than domes. Eureka’s Timberline tents are the classic A-frames and have been around since the 1970s. These have A-poles at each end and a curved ridgepole. They’re freestanding, and the lightest two-person model weighs 5 pounds, 13 ounces.

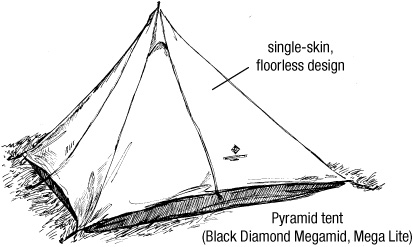

Long before the current lightweight revolution, Chouinard made a floorless tent called the Pyramid. Chouinard became Black Diamond, and the Pyramid became the Megamid and, in lighter form, the Mega Lite. These have an area of 81 square feet and can sleep four. The coated nylon Megamid weighs 3 pounds, 13 ounces; the silnylon Mega Lite weighs 2 pounds, 8 ounces. There’s an optional floor weighing 1 pound, 13 ounces. The tents come with adjustable shock-corded aluminum central poles, but the Mega Lite also has a pole converter that enables you to use two trekking poles instead.

The Pyramid/Megamid became popular with ski tourers, since the snow inside could be dug out for more space, something you can’t do with a floored tent, and it’s very light with lots of headroom. Other makers followed, and there are now several pyramid and tepee tents. I’ve used the 75-square-foot six-sided silnylon GoLite Hex 3, which has a canopy weighing 1 pound, 12 ounces, an 11-ounce pole, and 5-ounce stakes and stuff sacks for a total weight of 2 pounds, 12 ounces for a shelter that will sleep three and is very roomy for two. A floored mesh inner tent called the Hex 3 Nest weighs 2 pounds, 6 ounces. The Hex 3 proved a stable design when pitched for two nights in storms at 11,000 feet. The wind ensured that little condensation built up inside, though in calmer conditions there has been quite a bit. I’ve also used the Hex 3 on a two-week spring ski tour where the space was welcome. Cooking inside is no problem, and I really like being able to stand up to get dressed. Other makers of pyramid tents include Mountain Hardwear, Dana Design, Oware, and Kifaru, whose Tipis can incorporate a wood-burning stove (2 pounds, 5 ounces). The Ultralight 4 Man Kifaru Tipi weighs 4 pounds, 11 ounces.

Single-skin pyramid tent. GoLite Hex 2.

Not quite a pyramid but similar enough to mention here are the Wanderlust Nomad silnylon tents. These are designed to be pitched with trekking poles as either A-poles or central uprights and have a groundsheet and huge mesh panels overhung by coated nylon. They look quite innovative, being neither single skin nor double skin. The 28-square-foot Nomad Lite weighs 1 pound, 11 ounces, and the 45-square-foot Nomad 2-4-2 weighs 1 pound, 15 ounces.

Geodesic dome with fly sheet.

Geodesic dome.

Domes have two or more flexible poles crossing each other at one or more points. Many are free-standing—they don’t need staking down. This is often pushed as a huge bonus. It does indeed make pitching domes quicker and easier—if there’s no wind. But I’ve heard stories of domes taking off like giant balloons, never to be seen again. I would always stake down a tent. I have to say that although I’ve owned a few over the years and tested many more, I’m not particularly fond of domes. I prefer simpler designs that give more space for the weight and are generally easier to pitch. I seem to be in the minority here, however, since dome tents are by far the most popular design. Backpacker’s 2004 Gear Guide lists twenty-three companies offering over 160 models.

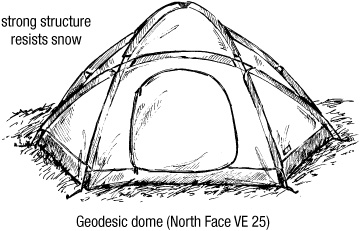

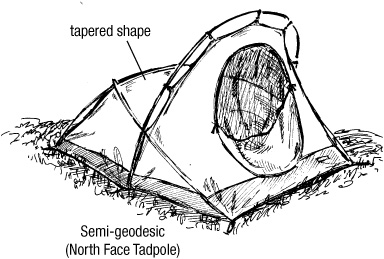

The two most common dome shapes are the geodesic and the crossover pole, though there are many variations. Geodesic domes are complex structures in which four or more long poles cross each other at several points to form very stable tents that are popular with mountaineers because they can withstand high winds and heavy snow loads. Crossover pole domes are simpler: two or three poles cross at the apex to make a spacious tent that is lighter than a similar-sized geodesic, though nowhere near as stable—in strong winds the poles can invert, and the whole tent can wobble like a gelatin mold. Weights run from 4 pounds for solo two-pole domes (sometimes called wedge tents) to 12 pounds for multi-pole tents that will sleep three or four.

A typical example of a simple wedge tent is North Face’s Roadrunner 2, at 5 pounds, 13 ounces. This has a tapered shape with two poles that cross toward one end rather than in the center. Pitch the narrow end into the wind, and the Roadrunner is quite stable for a crossover pole tent. The floor area is 33 square feet, and there are vestibules on both sides that add 9 square feet each. The fly sheet is made from ripstop polyester. There are two vents near the apex of the tent and two-way protected fly sheet door zippers, and the top half of the inner tent is made of mesh so ventilation is excellent, though condensation can drip through. The North Face also made one of the original geodesic domes, the VE24. This has become the silnylon VE25, with an added pole to create a larger vestibule at one end. It weighs nearly 11 pounds, but it has a floor area of 48 square feet and will stand up to almost anything.

Geodesics are very stable but not very light. Almost the same wind resistance can be obtained by adding a third pole across the front of a two-pole wedge and tapering the back of the tent to the ground to create a semigeodesic or geo-hybrid shape. On the Continental Divide Trail I used a 6-pound tent of this design (a long-gone model called the Wintergear Voyager) and found it roomy, durable, and stable in storms. For the first month of the hike I shared the tent with a companion. After that I used the tent solo, relishing the space but not the weight. One of the most popular semigeodesics for many years has been North Face’s Tadpole. The latest version weighs 4 pounds, 15 ounces, and has a 27-square-foot floor and 8-square-foot vestibule. The fly sheet is coated nylon, and there are mesh panels in the sides of the inner tent. I’ve used the Tadpole and found it a stable tent for two, though not very roomy because of the low rear and small area.

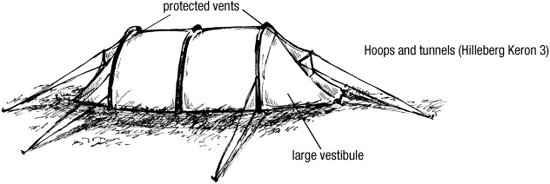

Rather than crossing, in tunnel tents the poles form parallel hoops. Tunnels have a better space-to-weight ratio than any other design. They’re also very easy to pitch, though they’re not freestanding. This category includes the tiniest tents, weighing about 2 pounds. For years I never tried one of these because they are so low and narrow that I felt claustrophobic just looking at them. This is hardly objective, however, so I did eventually brace myself and try a 2-pound, 5-ounce Bibler Tripod, which appeared to have slightly more headroom than most. The Tripod is made from waterproof-breathable Toddtex and has a tiny hoop at the foot and two poles at the head, one forming the main hoop, the other running at right angles to it and holding up the fabric at the end of the tent. This does give slightly more room than in tents with just two small hoops. (It also makes it debatable whether this is a hoop tent—it fits best here in my opinion, despite the third pole. Tent classifications are often fuzzy anyway.) With the doors closed the Tripod is very dark, but it didn’t prove quite as claustrophobic as I feared. Condensation was minimal—just a small amount on the groundsheet. I could prop myself up on my elbow and read inside, but there’s no room for any gear other than some clothes. It’s awkward getting dressed and undressed inside, too. In the conditions where I want a fully enclosed tent, I’d like more space—much more space. If I don’t need an enclosed shelter, I’d prefer a tarp. These minitents are light, but in my opinion they have more disadvantages than advantages.

Double-layer tunnel tent with poles on the outside—the exoskeleton design. Hilleberg Nallo 2.

Timberline camp with tarp pitched as a tapered ridge and two tapered tunnel tents.

Morning after a night of snow. Tunnel and geodesic dome tents.

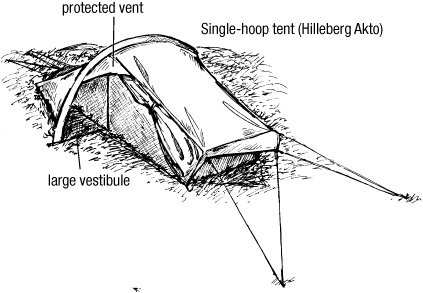

Single-hoop solo tent, the Hilleberg Akto—my favorite solo tent.

The simplest models that can be called real tents weigh from 3 pounds upward for double-skin (or double-wall) models and 2.25 pounds for single-skin ones. The latter can be as light as minitents, but being made from nonbreathable fabrics they’re much more prone to condensation, as I found when I tried the GoLite Den 2, a 3-pound, 9-ounce, two-pole model. The key to stability with tunnel tents is the distance between the poles. Large areas of material between the poles can flap and shake badly, so those with the poles close together are the most wind resistant. I used the 4.75-pound, two-pole silnylon Hilleberg Nallo 2 on a 1,300-mile Scandinavian mountains walk and found it very stable as long as I pitched the rear into the wind. Crosswinds shake tunnels, though, and one night the tent was thrashing about so much I got up about midnight and dashed out into the lashing rain to turn the tent 90 degrees into the wind. The difference was astonishing. Like all Hilleberg tents, the Nallo 2 pitches as a unit or fly first. It’s roomy enough for two and very spacious for one. I now use it on midwinter trips when more space is welcome on long dark nights and on trips where weight isn’t too significant.

The lightest tunnel tents, indeed the lightest tents for the size of any design, are made by Stephenson’s Warmlite. These are made of silnylon, and the weights are astounding—the smallest model, the single-skin 2X, weighs 2.3 pounds, yet it’s 60 inches wide at the front, 48 inches wide at the rear, 134 inches long, and 40 inches high at the apex, with an area of 42 square feet. There are inside stabilizer straps for use in high winds—Warmlite tents are said to be extremely storm resistant. The lightest double-skin model, the 2R, weighs 2.7 pounds. Both layers are made from silnylon, and they are permanently linked and pitched together.

There are several tunnel tents suitable for solo use, including the popular Sierra Designs Clip Flashlight at 3 pounds, 13 ounces. Larger tunnel tents often have three poles, sometimes of different sizes, with the largest placed in the middle to give more headroom. These are excellent for two or more people. I’ve had great success using large three- and four-person Hilleberg Keron three-pole tunnels (8 pounds, 9 ounces and 9 pounds, 11 ounces) for group snow camping.

Tunnel tents are the most popular tents after domes. Backpacker’s 2004 Gear Guide lists twenty-one makers and sixty-three models.

The problem with solo tents is that weight and size are related. Length has to remain constant, of course—one person needs the same space to stretch out as two—which means that width and height have to be reduced to cut the weight. In a slimmed-down version of a ridge, dome, or tunnel tent usually you can barely sit up. The solution is the single-hoop tent, a style that really works only for solo tents. As the name suggests, this design features one long, curved pole that may run across the tent or along its length. Single-hoop tents can be remarkably stable for their weight if the guying system is good.

My favorite tent is a single-hoop model, the Hilleberg Akto, that weighs 3 pounds, 7 ounces. I’ve been using this little tent since the early 1990s, and it’s stood up well to many nights of wild weather. Made from silnylon, it has a huge vestibule that stretches the length of one side, a protected vent above the door, and two lower vents at each end. A problem with single-hoop tents is that the fabric can be close to your face when you lie down, especially if you’re tall. Hilleberg has solved this with tiny corner poles permanently attached to the fly sheet that lift the ends of the tent a little.

One of the pleasures of backpacking is sleeping in a different place every night. This can also be one of the horrors if you’re stumbling around in the rain looking for a campsite long after dark. In popular areas there are plenty of well-used sites. Take the time to look at such places and work out why they’ve been used so much, and you’ll soon learn what to look for when selecting a site.

There are both practical and aesthetic criteria for a good campsite. A site with a good view is wonderful, as long as it’s also comfortable. For a good night’s rest you want as flat a site as possible. Often, however, you must make do with a slight slope; most people then sleep with their heads uphill (if I don’t, I develop a headache and can’t sleep). Sometimes the slope can be so gentle that it’s unnoticeable—until you lie down and try to sleep. I like to check sites by lying down before I pitch the tent. That way I also find any sharp stones or pinecones my eyes have missed. Beware of camping in hollows in wet areas, however, since rain may collect there.

If it’s very windy, a sheltered spot makes for a more secure and less noisy camp, though I often head uphill and seek out a breeze if bugs are a problem. Cold air sinks, so valley bottoms are often the coldest spots. Where possible I like a site that will catch the early morning sun, making for a warm and cheerful start to the day, so I look for sites on east-facing slopes and on the west side of valleys.

Water nearby is useful, though in dry areas like deserts I often carry enough for the last few hours of a day and the next morning and have a dry camp. It’s best not to camp right next to water; you could damage the bank and you may deter wildlife that needs access to the water. In many national parks and wilderness areas, the regulations forbid camping within a few hundred feet of water or trails. Camping well away from water and trails is best.

In popular areas there are usually many regularly used campsites, so finding one isn’t difficult (finding one that you don’t have to share can be harder). When I’m in country where such sites are rare or nonexistent, each morning I generally work out where I’m likely to be that evening and use the map to select a possible area for a site. Usually I find a reasonable spot soon after I arrive. If an obvious one doesn’t present itself within minutes, I take off my pack and explore the area. If this doesn’t produce a spot I’m happy with, I shoulder the pack and move on. At times, especially when daylight hours are short, this can mean continuing into the night.

When a possible spot turns out to be unusable and I have to keep walking, sometimes tired and hungry, I remind myself that a site always turns up; it may just require a little imagination to make the most of what seems unsuitable terrain. Perfect pitches are wonderful, yet many of those I remember best are the ones, like that in the northern Rockies (see sidebar, opposite), that were snatched almost out of thin air.

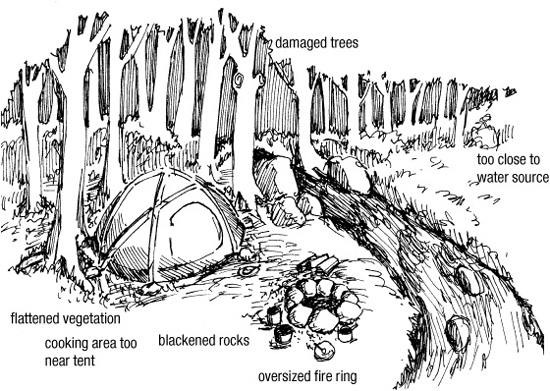

The most important aspect of selecting a site is to minimize your impact and leave the wilderness fresh and untouched, both for itself and for the next hikers.

All sites, whether previously used or not, should be left unmarked, which means no trenching around tents, no cutting of turf, and no preparation of the tent site. Previously unused sites should always—always—be left with no sign that anyone has been there. Camp on bare ground, forest duff, or dry vegetation such as grass that will be least damaged by your stay—which shouldn’t be longer than one night. Avoid damp ground and soft, easily crushed vegetation. If you’ll be staying more than one night on any site with vegetation, move your tent or tents each day to allow the plants to recover. Paths from tents to water, tent to tent, and tents to kitchen site are easily created if you’re not careful. You can reduce the number of trips by carrying a water container big enough to hold all the water you’ll need for overnight. Siting the kitchen so there is bare ground or rocks between it and the tents also cuts down the impact. Wear light footwear, not heavy boots, or go barefoot.

Tarp pitched in snow on a windy forested ridge.

A quality campsite (top) is sited away from water sources and critical vegetation, and shows that minimum-impact methods have been used. Not-so-good campsites (above) are those near overhanging dead tree limbs, in the middle of a field during a thunderstorm, in a canyon, next to water, on soft vegetation, and near avalanche threats.

Light fires only if you can do so without leaving any sign of them when you depart (see Chapter 7). If you use rocks to hold down tent stakes—rarely necessary, though often done, especially above timberline—return them to the streams or boulder fields where you got them; I’ve spent many hours dismantling rings of stones on regularly used sites. When you leave a wild site, make sure to obliterate all evidence that you’ve been there, fluffing up any flattened vegetation as a last chore.

Pitching camp on a forest site in spring.

Of course you’ll often camp on sites that have been used before. If possible, I pass by a site that looks as if it’s used only occasionally, perhaps stopping to further disguise the signs of its use. A well-used site, however, should be reused, because doing so limits the impact to one place in a given area. You should still try not to add to the damage, of course. Use bare patches for tents and an existing fire ring for a fire—if there are several, dismantling all but one is a good idea. Tidying up the site may encourage others to use it rather than make new ones. As with every site, leave nothing, and don’t alter the natural surroundings.

In some areas, particularly in the eastern United States, land managers have provided wooden tent platforms at many sites. Use them, since they are there to reduce impact. I first came across these in the White Mountains, New Hampshire. To stake tents down you need either very sharp, strong stakes that can be hammered into the planks or, preferably, long lengths of cord that can be attached to stake points, then run off the platforms and staked down or tied to trees. Freestanding tents would be ideal for tent platforms, but I had the Akto, which requires eight stakes. On the advice of a friend, I carried 50 feet of nylon parachute cord, and I used it all.

Wilderness camping is generally safe as long as you have the right gear and the necessary skills. However, there are some external dangers that you need to consider.

In forests, dead trees and branches can fall on your tent; it’s always wise to look up when selecting a site and not camp under dead limbs. If there are dead trees nearby, I like to be sure they’re leaning away from the tent. Trees don’t fall only in storms, either—the only time I’ve seen a tree come down was on a calm day. I heard a loud crack and looked up to see a large pine topple over and crash to the ground.