TWO ROADS DIVERGED IN A WOOD, AND I—I TOOK THE ONE LESS TRAVELED BY, AND THAT HAS MADE ALL THE DIFFERENCE.

—“The Road Not Taken,” Robert Frost

North America may well be the best place in the world for backpacking: it’s got a good trail network and vast areas of protected wilderness. Ironically, the excellence of the trails and the numerous published trail guides can lessen the adventure.

Trekking abroad can be different. There are few places in the world where hiking isn’t possible, though it may be very different from what you’re used to at home. In Europe there’s a huge network of well-maintained trails; mountain lodges that provide beds, meals, and heating are found in many areas, including the Alps, the Pyrenees, and the Scandinavian mountains, making long-distance walks with very light loads possible. To explore the more remote areas, “primitive” camping is still necessary, of course (and many, including me, prefer it, at least in good weather).

A mountain hut in the Queyras Alps, France.

European hikers often carry their own gear, but in many countries porters or pack animals are used, as in that ultimate hiking destination, the Himalaya. Treks there usually involve porters—one or two for small groups, up to forty for large, organized trips. Tea houses are found on the most popular routes, such as the Annapurna Circuit or the Everest Base Camp Trek, but in most areas all your supplies have to be carried in. The same system is used in Africa for ascents of mountains like Kilimanjaro.Other foreign hiking opportunities range from the rain forests of Costa Rica and other Central and South American countries to the deserts of Australia or Israel.

Charkabhot village, Dolpo, Nepal.

High on the Hardangerjøkulen ice cap, Norway.

Not all these areas are “wilderness” by the North American definition; in the Alps, the valleys are cultivated (in fact, alp means mountain meadow); in the Himalaya, the hiking trails are highways for the local people, used for trading and travel. Some areas are untouched and remote, however: most of Greenland is a mass of uninhabitable ice, as is Antarctica.

Long-distance trails exist in many countries. You can walk from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea along the spine of the Pyrenees on the 500-mile Pyrenean High Level Route or cross the Arctic Circle on Sweden’s 280-mile Kungsleden (the King’s Way). Other well-known trails are New Zealand’s Milford Track in the Fiordland Mountains, the Tour of Mont Blanc in the French Alps, England’s 270-mile Pennine Way, the High Level Route in Corsica, the Concordia Trek in the Karakorum, the Ascent of Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, and the Annapurna Circuit and the Everest Base Camp Trek in Nepal.

Two books with general introductions to these and other international hikes are Classic Treks: The 30 Most Spectacular Hikes in the World, edited by Bill Birkett, and The World’s Great Adventure Treks, edited by Jack Jackson. Where long trails don’t exist, it’s usually easy to link shorter trails to make through-routes or circuits, just as you would at home.

The problems of hiking in some of these areas mainly concern information and organization. Only the most experienced travelers can set out for unknown foreign destinations on short notice and with minimal planning—and even then chances are something important will be overlooked.

Foreign adventure travel is often considered expensive, but this is true only if you want to visit a place like Antarctica. Indeed, you can visit many places for less than it would cost to hike in some areas of North America. If you live on the East Coast, a visit to Costa Rica or even Nepal may be less expensive than an airline flight to the Southwest—and certainly less than one to Alaska. Although the airfares may be higher, the ground costs are much, much less.

It’s not difficult to learn what to expect at most hiking destinations. At an outdoor store, bookstore, or library you should find guidebooks to most countries and areas. Many, of course, are designed for auto travelers and “tourists” rather than trekkers. Lonely Planet, Rough Guides, Bradt, Sierra Club Books, and Mountaineers publish books covering areas outside North America that are suitable for hiking. Most include general information about the countries, along with details of towns and popular destinations. Some have details of specific hikes, as well. There are trekking guides for many areas such as Nepal and other Himalayan countries. John Hatt’s The Tropical Traveler covers everything a first-time traveler could want to know in an entertaining and informative way. Its focus is the tropics, but the general information is just as useful for trips to other areas.

Travel guides can never be completely up to date, however, and they may not include the information you require. Tourist boards can be helpful, as can national parks and other land-management agencies, especially for Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. All this information can be found on the Web, now the main research tool.

Many trekking guides contain maps; some, such as those for many European long-distance paths, may even contain topographic maps. However, for most trips you’ll want separate maps. These can be ordered at home from Web sites such as maplink.com or bought at your destination. I prefer to buy maps before the trip so I can use them for planning. Map quality varies enormously from country to country; some are barely more than sketches. I used basic 1:250,000 maps on a trek in the remote Dolpo region of Nepal. We crossed three 17,000-foot passes on that trip, none of which was named or had a height assigned on the map. Adapting to the scale was difficult, and the lack of detail made walking interesting in places—cliffs and gullies appeared in front of us that weren’t on the map. Most foreign maps and trekking guides use metric measurements, so you should become familiar with measuring in meters and kilometers before a trip.

On a high pass in the Himalaya, Dolpo, Nepal.

Once you have general information and an idea of where you want to walk, you can get to the specifics. Making lists may seem tedious, but I find they’re the only way to ensure I don’t forget anything. One is a gear list, tailored to the area and weather conditions expected; a separate list covers items you need for travel but that you won’t take backpacking, such as extra toiletries and clothes. Perhaps the most important list is for the essentials—passport, airline tickets, foreign currency, and addresses of hotels, contacts, and embassy. (I leave a copy of this list at home, along with an itinerary, in case people need to contact me.) This last list should be kept in a secure place while you travel; I use a small nylon pouch that I can hang around my neck or over my shoulder (under my clothes) for all documents, including passport and tickets. When hiking, I keep it in an internal pack pocket.

A typical information list contains two sublists: information common to every trip and that specific to a particular trip. John Hatt describes a good way to organize this in The Tropical Traveler. The list below is adapted from his.

Passport number with date and place of issue

Passport number with date and place of issue

Credit card numbers and bank’s telephone number and e-mail address

Credit card numbers and bank’s telephone number and e-mail address

Home doctor’s name and telephone number and e-mail address

Home doctor’s name and telephone number and e-mail address

Camera equipment with serial numbers

Camera equipment with serial numbers

Camera insurance policy number and insurance company phone number

Camera insurance policy number and insurance company phone number

Embassy address and telephone number and e-mail address

Embassy address and telephone number and e-mail address

Travel insurance number and telephone number for claims

Travel insurance number and telephone number for claims

Medical emergency telephone number

Medical emergency telephone number

Plane ticket booking reference number

Plane ticket booking reference number

Plane ticket serial number and date of issue

Plane ticket serial number and date of issue

Dates and times of flights

Dates and times of flights

Telephone and booking numbers of the flight-booking agent

Telephone and booking numbers of the flight-booking agent

Phone card numbers

Phone card numbers

Telephone code from home

Telephone code from home

Telephone code to home

Telephone code to home

Traveler’s check numbers

Traveler’s check numbers

Contact address

Contact address

One way to avoid having to do all the trip organization yourself is to go with an adventure travel company. These trips vary from “catered” ones—your gear is carried by porters or pack animals and all the cooking and even tent pitching is done for you—to ones where you carry everything and do most of the work yourself. (The ski tours I led in Scandinavia fell into the latter category.)

Organized trips can be fun and a good way to experience a new country. You do need to be comfortable traveling and hiking with a group and with a specific itinerary, however. Most companies give you all the details, such as how many people will be on the trip, how far you’ll walk each day, how difficult the walking will be, how many days will be spent walking and how many in motorized transport (some trips can involve more motor travel than walking), what to bring, and what type of weather to expect.

Foreign travel, especially to developing countries, often raises health concerns. The first thing to do is discuss the trip with your doctor to find out what immunizations you’ll need. Do this well in advance of the trip—some shots may be necessary weeks before you go. You also need to know what other medication it would be advisable to carry, such as malaria pills. I always take a broad selection of antibiotics, plus a strong prescription painkiller (remember to bring copies of any prescriptions to show officials).

Water can be a problem in developing countries, or in any remote area—some foreign waterborne diseases make giardiasis look like a slight cold. The biggest danger is from viruses—unless they have a chemical disinfectant built in, filters do not remove viruses. Iodine is the standard water treatment; I used the Polar Pure Iodine Crystal Kit when I went trekking in Nepal for two weeks and had no problems, though I did come down with a nasty stomach ailment in Katmandu (which I blame on brushing my teeth with unpurified tap water in my hotel). I found being careful much more difficult in the city than in the wilderness.

Eating different foods is one of the joys of adventure travel. Finding quick-cooking ones suitable for backpacking can be difficult, though, so I usually carry some dehydrated meals. This applies even in Europe; I’ve resupplied with some very odd selections from tiny village stores in the Pyrenees and ended up carrying loaves of bread and tins of beans at times because I couldn’t find dried items.

Fuel supplies can be even more of a problem. White gas is almost impossible to find outside North America. If this is all your stove runs on, you’ll need gasoline (which could cause clogging). Far better is a stove that will run on kerosene, a common fuel in the Third World. (It’s usually not very clean, though, so bring a filter funnel.) The MSR XGK II is probably the best stove for international travel because it will run on any type of petroleum, clean or dirty, and is easily maintained in the field. In Europe, butane-propane cartridges are common, and alcohol can be found in many countries, especially Norway and Sweden. By the way, knowing the local name for your fuel is important: In France kerosene is called pétrole, but in Britain petrol means gasoline (kerosene is called paraffin).

If you plan to take photographs, take along all the film you expect to need when visiting developing countries; carry spare batteries, too. In Europe, film is easy to find but is more expensive than in North America. On long trips, bringing a second camera is a good idea because making repairs or finding spare parts is likely to be impossible in most places. I know people who carry three cameras—the third usually is a small compact, carried “just in case.”

Comprehensive travel and medical insurance is essential. For backpacking, it’s important to check that hiking and camping are covered in your policy—many general travel policies don’t cover you during such activities. Gear and cameras need insurance, too. Carry a list of camera gear serial numbers, both in case of a claim and in case a customs inspector asks you where you bought your gear. If you can’t show where you purchased it, you could face hefty import charges.

A self-catering hut in Norway.

Meeting people from different cultures can be one of the great pleasures of adventure travel. But it’s important to learn something about their cultures in advance so you can avoid behaving offensively or disrespectfully. Good guidebooks have details for specific countries. Knowing just a few phrases of the local language can help with communication; phrase books can be useful, but most are geared to general tourism and don’t include the words you need while backpacking. Trekking guides are usually better. Stephen Bezruchka’s Trekking in Nepal has an excellent appendix on Nepali for trekkers.

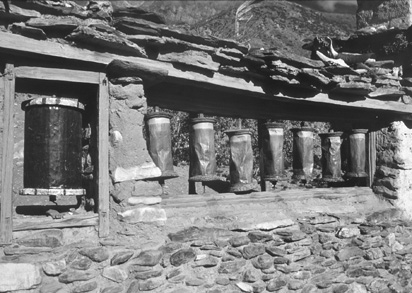

Buddhist prayer wheels, Dolpo, Nepal.

When employing local people as porters, you have a responsibility if problems arise. You’re on a vacation, but they’re working. In the fall of 1995, a huge snowstorm swept areas of the Himalaya in Nepal, killing many people—locals and trekkers—and causing serious problems for trekking groups. Some of the stories that came out of this disaster are very disturbing, including tales of trekkers’ abandoning porters to die in the snow while they took helicopter flights back to Katmandu or refusing to let locals use tents and other equipment. Some of those involved were trekking companies. I suggest quizzing any company you’re thinking of traveling with about how they treat their porters and what provisions are made for them in emergencies. On the other hand, some trekkers went out of their way to assist porters and local people, and some companies treated porters and clients exactly the same, which is as it should be. I don’t want to imply that all trekkers behave badly.

Internal travel can be exciting. I’ve been petrified in a taxi on narrow winding mountain roads in the Spanish Pyrenees, bumped in a car over a potholed highway in Nepal, chugged down an iceberg-dotted fjord in a fishing boat in Greenland, and helicoptered just above glacier-filled valleys in the same country.

The most exhilarating, overwhelming, and downright terrifying journey I’ve ever made was in a small passenger plane in Nepal, from Nepalgunj in the lowlands to Juphal, high in the Himalaya. The little plane, packed to bursting with people and baggage, flew into a narrow mountain valley with dense conifer forests on each side, the treetops so close it seemed you could pluck cones through the windows. Our altitude was 17,000 feet, high enough to clear most mountain ranges, but here the peaks soared to 26,000 feet and more on each side, towering masses of rock and ice. I checked my watch, which indicated we should be landing in a few minutes. I looked down: below, a winding river slid through the dense forest; clearings or flat land were nowhere to be seen. Through the cockpit window I could see a spur of the mountainside cutting across the valley—we were flying straight at the top of it. Surely the pilot would climb, I thought. But no, on we went toward what seemed an inevitable crash. Finally we cleared the rocky edge of the spur, the wheels touched down, and we bumped to a halt on the sloping field that constituted Juphal airport. These are known as STOL airstrips—short takeoff and landing.

A traditional Sami hut, Sarek National Park, Arctic Lapland, Sweden.

Monte Viso from the Col de Chamoussiere, Queyras Alps, France.

In other places, internal travel can be the opposite, a time to relax in comfort. I especially love the train journey through Norway and Sweden to the Arctic, with the big, well-appointed trains drifting north through increasingly wild, snowy northern landscapes. At night there are comfortable beds to sleep in, and for breakfast coffee and donuts are served in the restaurant car.

Whether by car, coach, train, boat, or plane, getting there takes time. Rather than viewing it as a means to reach the mountains or trailhead, it’s better to treat it as an element of the adventure, as part of experiencing what a new country has to offer.