Asked to list their favourite garden birds, most people would put the robin, often known as the ‘gardener’s friend’, at or near the top. Other common visitors to our gardens include the tits and sparrows and a host of finches.

The robin’s song, boldness and cheery appearance have long endeared it to us, and, indeed, it is usually regarded as Britain’s national bird.

A recent survey conducted by the British Trust for Ornithology revealed that robins were present in 99 per cent of the gardens surveyed. They stay with us throughout the year, although we do not see or hear much of them for a few weeks during late summer. This is the moulting period, when their old feathers are replaced and flying is curtailed, but as soon as they have regained their red breasts, the birds waste no time in redefining their territories and defending them with song and aggressive displays.

Courtship and nesting

Males and females sing and display with equal vigour, and for several months each bird remains fiercely independent, even attacking any other robin that dares to encroach upon its territory. As autumn turns into winter, however, the barriers begin to come down and the females are allowed into the males’ territories.

‘Engaged’ pairs may feed close to each other, but otherwise have little contact until the spring. The male continues to defend his territory with song, but the female gradually stops singing and gets ready for the breeding season. She builds the nest unaided in the spring, choosing a fairly low, dark hole if possible.

CJ Wild bird Foods/David White

The nestling with the widest gape – usually the hungriest one – will generally get the grub. This is nature’s way of ensuring that all the nestlings get their share.

Michael Chinery

A robin will learn to take mealworms from your hand in just a few days. Offer the worms on the ground in front of you at first.

An open-fronted box, hidden in a dense hedge or on an ivy-clad wall, makes an ideal home. Robins are also said to be happy with an old kettle wedged in a hedge with the spout pointing down to prevent water-logging. However, the one that I placed in my hedge has been totally ignored for 25 years!

Leaves and moss form the bulk of the cup-shaped nest, which is then lined with fine roots and hair. There is usually no shortage of nesting materials in a normal garden, but if you hang up a bag of moss, wool and hair (see here) you will be able to enjoy watching the hen tugging out the pieces and cleverly manipulating them with her beak before flying back to her nest. Breeding usually starts in March or April and the robins may raise two or even three broods during the next three or four months.

While the female is building the nest and incubating the eggs, the male feeds her regularly. She utters a short, sharp call to tell him where she is and he obediently shoves some food into her open beak. This courtship feeding is easy to watch once you have located the female. If you maintain a regular feeding station, the male will return to it every few minutes throughout the day, periodically stopping to re-fuel himself between visits to his mate.

The menu

Robins will eat almost anything that they can get their slender beaks round or into. Sultanas and other dried fruit, grated cheese, cake crumbs and bird pudding (see here) are all very acceptable, but the birds are essentially insect-eaters and they will do almost anything for a feed of mealworms. Once a bird has learned where mealworms are on offer, it will tap on the window to ask for them and may even enter the house to seek them out!

CJ Wild bird Foods/David White

An open-fronted nest box is ideal for robins, especially if it is partly concealed by creepers and other vegetation. Notice that the young robins do not have red breasts. The colour does not develop until the birds moult in late summer.

Easily identified by the bright blue crown, blue tits are present in virtually every British garden, especially in the winter. You may think there are just a few resident birds in your garden at this bleak time of year, but it is quite likely that dozens of blue tits pass through each day, staying just long enough for a snack.

Blue tits are essentially insectivorous birds, using their tiny pointed beaks to pluck caterpillars, aphids and many other insects from trees in summer. In winter, they scour tree trunks and branches for aphid eggs and spiders, although seeds are more important at this time.

Like all the other tits, the blue tit is an inquisitive bird and readily finds and adapts to new sources of food. The birds display amazing agility while taking peanuts from a variety of feeders, and their habit of pecking through milk bottle tops to get at the cream is equally well known.

Blue tits are hole nesters and, like great tits, they will readily nest in traditional tit-boxes (see here). The female builds the nest herself, using plenty of moss and hair or wool, and she alone incubates the eggs while the male bird works hard to keep her supplied with a diet of juicy caterpillars.

CJ Wild bird Foods/David White

The great tit is distinguished from the blue tit by its larger size and black crown.

CJ Wild bird Foods/David White

The coal tit has a black crown with a white patch at the rear. It usually feeds high up in the trees, especially in conifers, but comes to bird tables in the winter.

CJ Wild bird Foods/David White

The blue tit is a sharp-eyed hunter, able to spot the tiniest of insect eggs in bark crevices and pluck them out with its tweezer-like beak. Give them a comfortable nest box and a pair might well rear a brood of nine or ten babies.

If you live in a town you might think the house sparrow is one of our commonest birds, but this is far from the truth. House sparrows, distinguished by the dull grey crown, are rarely seen far from human habitation, and huge tracts of the countryside have no house sparrows at all.

House sparrows are very sociable birds and where they occur they are often seen in large numbers, feeding on seeds and any scraps that they can glean from streets and gardens. Although they are basically ground-feeding and not as acrobatic as the tits, they are perfectly happy on the bird table and quite good at extracting peanuts from various feeders.

They usually nest in small colonies, with several pairs of birds living on a few neighbouring properties. The rest of the street may have no nests at all, although the sparrows may well feed there. The untidy nests are made largely of grass and straw but also include wool, feathers and anything that takes the birds’ fancy. Give them some cotton wool and watch the fun as they squabble over it! Nests are usually built on houses, especially on creeper-clad walls, or in dense hedges, and the birds appreciate open-fronted boxes or tunnels (see here) fixed in sheltered spots. A colony may exist for several years but then, for no obvious reason, leave and settle in another part of the town or village.

CJ Wild bird Foods/David White

The black bib of the male house sparrow is smaller in winter. Females have no bib at all.

Colin Varndell

Although often called a hedge sparrow, the dunnock is not a sparrow at all – look at its much narrower beak. A common garden bird, it nearly always feeds on the ground.

CJ Wild bird Foods/David White

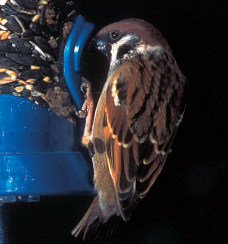

The tree sparrow differs from the house sparrow in having a chestnut crown and white cheeks with a black patch in the middle.

DECLINING POPULATIONS

House sparrow populations have declined sharply in recent years, the most likely explanation being that modern or modernized houses do not provide enough nesting sites. Whatever the reason for their decline, feeding these sparrows in our gardens can only do good. They might damage a few crocuses and spring flowers as they drink the nectar, but our gardens would be much poorer without these cheerful squabblers.