Anno 1634, Easton Pierse

I WAS BORN about sun rising in my maternal grandfather’s bedchamber on 12 March 1626, St Gregory’s Day, very sickly, likely to die. I was christened before Morning Prayer. My father was nearly twenty-two years old, my mother only fifteen and a half. She has cried through the night and given birth to three more babies since, but they have all died.

My mother’s father, Isaac Lyte, is a man of the old time: he wears a doublet and hose and carries a dagger, as men did in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. He is a living history. We live with him at Easton Pierse, a hamlet in the parish of Kington St Michael, in the hundred of Malmesbury, in the county of Wiltshire.

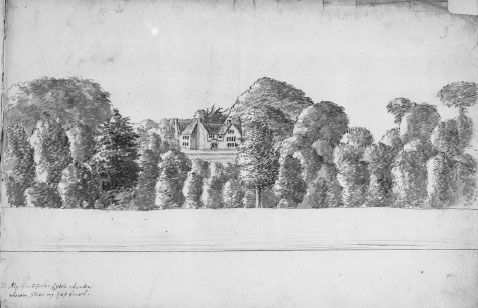

My grandfather tells me1 that our family sold the manor house and farm at Easton Pierse to the Snell family in 1575, the year before he was born. The house we live in now was built the year following, on the brow of the hill, above the brook, facing south-east. It has a great hall and parlour and a tall, carved chimney stack. In the parlour chimney is carved: ‘T. L. 1576’, my great-grandfather Thomas Lyte’s initials and the year our house was built.

On the chimney in my grandfather’s chamber, where I first drew breath, there are two escutcheons. The first for my grandfather: ‘Isaac Lyte natus 1576’. The second for my grandmother, Israel Lyte, whose family name before she married was Browne.

. . .

At home I am often alone. I watch the joiners, carpenters and stonemasons when they are hard at work rebuilding the manor house next door. Sometimes they give me scraps of their materials and lend me their tools. I fancy myself an engineer. I wish I lived near Bristol like my father’s mother. In a city I would be able to visit the watchmakers and locksmiths and learn their trades instead of learning grammar. I can understand grammar easily, but struggle to remember it. I like to dream. I like to think about the past.

. . .

I like to ask2 the old men and women for stories. When I was smaller, old Jack Sydenham, the Snell family’s servant, would swing me high in his arms. He lives at Kington St Michael, near the old priory across the brook. He tells me that long ago the old priory was full of women: nuns, widows, grave single women, and young maids, learning physic, writing, drawing, etc. In memory of those women, the meadow is called Nymph Hay. They used to spin there in the morning with their rocks and spinning wheels. On Fridays there was a market at the crossroads for the nuns to buy their fish, eggs and butter. There is no market now. My grandfather remembers that in his grandmother’s time the tablecloth would be spread all day with food and drink to offer to pilgrims and other travellers passing by. But since the dissolution of the monasteries and religious houses, no one comes.

. . .

I lie on the bank3 of the brook and dig idly in the blue clay. I count and name the plant types: calver-keys, hare parsley, wild vetch, maiden’s honesty, polypodium, foxgloves, wild vine, bayle, cowslip, primrose, adder’s tongue and others whose names I do not know. It seems to me a kind of ingratitude not to care about the plants that grow round about our dwellings, since we see them every day and they nourish us.

. . .

The north part4 of Wiltshire between Chippenham and Malmesbury is stiff clay; the parish of Kington St Michael especially. Wormwood grows plentiful, as does woodwax and sorrel, an abundance of sower herbs and brook lime. It is an excellent place for plants. Our soil is very good for oaks and witch hazel trees.

The stones at Easton5 Pierse are full of small cockles, no bigger than silver halfpennies. The stones at Kington St Michael and Draycot Cerne are also cockley, but the cockles of Draycot are bigger.

. . .

I am so bored6, so alone. My imagination is like a mirror of pure crystal water, which the least wind does disorder and unsmooth. So noise, etc., stirs me. I have been told that I was late to learn to speak. I still stutter on certain words.

. . .

When I was learning7 to read, I found a flint as big as my fist in the west field by our house: it was a kind of liver colour. Such coloured flints are rare.

. . .

I love to read8. My nurse, Kath Bushell of Ford, taught me my letters from an old hornbook. The letters were black and purple and difficult to recognise. The parish clerk of Kington St Michael first taught me to read. His aged father was clerk before him and wore a black gown every day with the sleeves pinned behind, which was fashionable in Queen Elizabeth’s time.

I started school9 in the church at Yatton Keynell: the parish next to Kington St Michael, where my mother was born. My grandfather went to the same school. There used to be a fair and spreading yew tree in the churchyard there; we boys delighted in its shade and loved to sit under it to learn our grammar; it furnished us with scoops and nutcrackers. But it was lopped to make money from its branches and died; the dead trunk stands there still.

There is another10 remarkable tree in our parish: a great oak at Rydens. It was struck by lightning, not in a straight but in a spiral line, which wound one and a half times round the tree, as a hop twists about the pole. The scar in the bark looks like it was made with a gouge.

. . .

Mr William Stumpe is the rector at Yatton Keynell: he is the great-grandson of a great clothier from Malmesbury who purchased the site of the abbey and some of its neighbouring lands. Mr Stumpe has inherited several manuscripts that came from Malmesbury Abbey. He says that when he brews a barrel of special ale he stops the bunghole, under the clay, with a sheet of manuscript and, according to him, nothing works so well: my eyes prick with tears at the thought. Even before I could read, I loved to look at the parchment pages that covered the books of the older boys.

. . .

I have moved11 to Mr Latimer’s school at Leigh Delamere, which is in the next parish and better. Manuscripts are used to cover books at my new school too. Now I can decipher some of them. My grandfather says that in his time all music books, account books, copybooks, etc. were covered with pages of antiquity, and the glovers at Malmesbury even used them to wrap their gloves for sale. He says that over the last century, a world of rarities has perished hereabouts. Before that, they were safe in the libraries of Malmesbury Abbey, Broad Stock Priory, Stan Leigh Abbey, Farleigh Abbey, Bath Abbey and Cirencester Abbey. All these old buildings are within twelve miles of my home. But when the great change – the Dissolution – came, the religious houses were emptied, the occupants all turned out in the road, and their manuscripts went flying around like butterflies through the air. A hundred years later, it seems to me that they are still on the wing. I would net them if I could. It hurts my eyes and heart to see fragile painted pages used to line pastry dishes, to bung up bottles, to cover schoolbooks, or make templates beneath a tailor’s scissors.

. . .

My fine box top12 has been stolen from me. At the age of eight I have learnt what theft is. I know that I am lucky not to have learnt before now.

. . .

In Latin lessons13 I have learnt the first declension without a book and it has made my head ache, or perhaps the heat of the weather we are having this May is to blame.

. . .

My most distinguished ancestor14, my paternal great-grandfather William Aubrey, was a fine statesman and a Doctor of Law. He argued against the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots but Queen Elizabeth forgave him and called him her ‘little doctor’. He lived at Kew, a mile from Dr Dee, the learned alchemist, who lived at Mortlake. When she was a child, my grandmother often saw them together. In the house of Dr Dee, I have heard, they used to distil eggshells and other revolting ingredients: menstrual blood, human hair, clouts, chalk, shit and clay. The children were frightened because they thought Dr Dee was a conjuror of evil spirits.

I do not think I would have been frightened of him.

. . .

My nurse, Kath15, presses her cool hand to my forehead. I have been lying in bed all day. I was riding my pretty horse back from school when I had a premonition I would fall: a briar swept against my face; the horse bolted. I cannot remember them carrying me home. My body woke to vomit. Nothing, I think, is broken. It is just the ague come upon me again. The ague is my earliest memory; since I was about three or four years old, it has come regularly: my stomach wringing itself into knots, like a rancid wet sack, trying to turn inside out. Moments before, when I know it will happen, I scrabble at the sheets. I need to vomit; I need it to be over; I need it not to begin. There is pain. There is blood. There is bile. There is nothing left inside me. I fall back, my body slack around the tight little ball below my ribs. I had measles too, but that was nothing: I was hardly sick.

Kath knows the history16 of England in ballad from the Norman Conquest down to the reign of the present King. She learnt it when she was young, sitting up late by the fireside, where fabulous stories of the olden days are passed from grandmother to mother to daughter: stories of sprights and the walking of ghosts. Many women cannot read. Kath can, but she still loves the old songs and all the frightening fables she learnt the same way. She believes in spirits, ghosts and fairies; so, sometimes, do I.

. . .

I am newly recovered17 from a violent fever that almost carried me off. But now there is fluid running from a lesion in my head that will not stop.

. . .

It is venison season18. As I arrived at school today, I overheard a tall stranger ask about me of my teacher Mr Latimer, who still wears a dudgeon with a knife and bodkin in the old-fashioned style. The stranger was our Malmesbury philosopher, Mr Thomas Hobbes, returning to visit the man who had been his teacher too. Mr Hobbes is over forty but has no streaks of grey in his crow-black hair. He was born in Malmesbury, his father was the vicar of Westport, the parish outside the West Gate of the town, and his brother Edmund, a glover, lives here still.

When he looked up at me on my little horse, there was kindness in his bright eyes that are hazel colour. When he laughs, his eyes almost disappear. He told me that we boys are lucky to have Mr Latimer, who is a fine Grecian, the first in Wiltshire since the Reformation. When Mr Hobbes was a boy, some years older than I am now, but not many, Mr Latimer encouraged him to translate Euripides’s Medea from Greek to Latin iambics. He did it and presented the manuscript to Mr Latimer, who must still have it somewhere. Whenever we leave the class to go for a pee, Mr Latimer gives us a Latin word and we have to give it back to him upon returning. It is a good teaching method, by which he gives us a store of words without us noticing.

Mr Hobbes went to Oxford19 at fourteen in the year 1603. His uncle, another glover, paid. Malmesbury is good for gloves and glovers. Mr Hobbes, who is tutor to the young Earl of Devonshire, will leave for a tour of Europe in a matter of weeks, but when he is back I hope we will know each other well for a long time.

Riding home, I felt happy. I have invited Mr Hobbes to meet my family tomorrow. He says he will come. He will stay in Malmesbury for a week or so. Something has happened to me and more will happen to me. This meeting seems an end to my loneliness. Mr Hobbes’s kind words were still in my mind this evening as I turned into Bery Lane, where there were two women in conversation beside a laburnum bush, one old, one young. They turned their backs. Malmesbury is good for witches too. They like the mud.

Here are some20 of the bad things witches can do: twist trees; tear and turn up oaks by the roots; raise tempests; wreck ships; tumble steeples; blast plants; cause whirlwinds and hurricanes; dwindle away young children; bind spirits and imaginations; make men impotent and women miscarry.

. . .

I rode over21 to the old stones at Stonehenge today. I go often and know them well. About two or three miles from Andover is a village called Sarsden: Caesar’s dene on Caesar’s plains (also known as Salisbury Plain). The Sarsden stones peep above the ground a yard or more high. Those that lie exposed to the weather are so hard that no tool can touch them. They take a good polish. As for their colour, some are a kind of dirty red, towards porphyry; some perfect white; some dusky white; some blue, like deep blue marl; some an olive greenish colour; but generally they are whitish. Stonehenge – that stupendous antiquity – is framed from these stones.

Sir Philip Sidney22, one of Queen Elizabeth’s courtiers, wrote verses about Stonehenge almost a hundred years ago:

Near Wilton sweet, huge heaps of stones are found,

But so confused, that neither any eye

Can count them just, nor reason try

What force brought them to so unlikely ground.

But it must be possible to count and number the stones. I will do so one day.

. . .

My honoured teacher23, old Mr Latimer, has died. There will be an inscription for him on a stone under the communion table in the church of Leigh Delamere.

. . .

I love the music24 of the tabor and pipe that is played especially on Sundays, holy days, christenings and feasts.

. . .

Above alderman and woollen draper25 Mr Singleton’s parlour fireplace, in his house near the steeple in Gloucester, there is a moving screen, a thing of marvels. One long strip of paper, the length of the room at least, pasted together from printed pages, and rolled like cloth, tight at each end on a tall pin. The pins are secured either side of the chimneypiece, and if you stand at one end and turn, you see the figures from Sir Philip Sidney’s funeral procession march by all in order, a glow beneath their feet.

First come thirty-two poor men, one for every year of Sidney’s life. Next come the band, playing but softly on their flutes and drums; the standard bearer, with lowered and trailing flag; trumpeters, corporals, officers of his horse; statesmen, gentlemen, servants, friends. It took fourteen to carry the body of the soldier, courtier, poet in its leaden coffin below its velvet drape, to its resting place in St Paul’s Cathedral. Sidney died after the Battle of Zutphen from a bullet-torn thigh, almost fifty years ago. At his funeral, on 16 February 1587, Queen Elizabeth and her nation mourned.

Today I watched Sidney’s funeral on the screen while my father talked of business in Alderman Singleton’s study. I know something of Sidney already. I have heard my great-uncle tell stories of how, out hunting on Salisbury Plain, he would stop suddenly to make notes for his Arcadia in a pocket book; I like the idea that the muses visited Sidney on horseback. I wonder what it would be like to be visited by muses?

In the parlour I turned the pin to make the figures walk forwards and back, over and over, so I could study their faces and clothes more carefully. The figure of Daniel Bachelar caught my eye, a boy like me, Sidney’s page, perched on a great horse caparisoned with golden cloth. I have heard people say that when Sidney lay dying, Daniel sang him verses from Arcadia:

Since nature’s works be good, and death doth serve

As nature’s work, why should we fear to die?

Since fear is vain, but when it may preserve,

Why should we fear that which we cannot fly?

Fear is more pain than is the pain it fears,

Disarming human minds of native might;

While each conceit an ugly figure bears,

Which were not ill, well viewed in reason’s light.

But I am not brave like Sidney. I am frightened of death.

When my father’s business was done today, I rode my own small horse home beside him. I love but scarcely know my father. He was born for hawking, whereas I know already that I am made for books and drawing. What I desired to do today was to sketch the contours of the countryside from Gloucester to Cirencester and back home to Easton Pierse, taking note of all the old buildings that we passed on our way. But it would have angered my father to wait for me on his tall horse, treading a muddy impatient circle. So I will save my drawing for the long empty days in our parlour, where there is no moving screen to distract me. I wish I could see and turn that screen again. I will always remember it.

. . .

My grandmother, Rachel Danvers26, was widowed in 1616, when my father was about thirteen years old. Afterwards, she married Alderman Whitson of Bristol. She was his fourth wife and they had no children of their own. Alderman Whitson was a good stepfather to my father. He taught him to hawk. He cut down woods my father had inherited and never gave him any compensation, but did him plenty of good too. My father says his stepfather lived nobly: he was the most popular magistrate in the city; always chosen as a Member of Parliament. Alderman Whitson was my godfather, but he died when I was about three years old, so I do not remember him. He was pitched from his horse and hit his head on a nail that stood on its head outside a smith’s shop. Seventy-six poor old men and women followed his coffin: one for every year of his age. He was the colonel of the trained band, who came to his funeral with black ribbons on their pikes and black cloth on their drums.

. . .

Since Alderman Whitson’s death27, my grandmother lives outside Bristol, at Burnett in the parish of Compton Dando, about two miles from Keynsham. About four miles from Burnett is Stanton Drew, where I go whenever I am staying with my grandmother because there is a monument of ancient stones behind the manor house there, which the people round about call the Wedding: it is far bigger than Stonehenge. The story (which I do not believe) is that on her way to be married, a bride and the company she was with were all turned into these stones, which are grouped together, hard as marble and nine or ten feet high. One is called the bride’s stone, another the parson’s stone, another the cook’s. The stones are a dirty reddish colour and take a good polish. I cannot help wondering how they really came to be there, and why.

. . .

When we are not28 at Easton Pierse in north Wiltshire, we live at Broad Chalke farm in south Wiltshire, close to the River Ebble. Here the bells of Broad Chalke church ring agreeably alongside the music of the running river. Just a short walk across the valley from our farm there is Wilton House, where Sir Philip Sidney and his beloved sister Mary, Countess of Pembroke, lived in their time. Our families are distantly connected. I have not tried to count the many volumes in the grand library at Wilton. There are a great many Italian books, books of poetry and polity and history. There is Sidney’s translation of the whole Book of Psalms into English verse, bound in crimson velvet and gilt. There is a manuscript of a Latin poem from Julius Caesar’s time. There are books of coats of arms and genealogies and histories of the English nobility: all well painted and written.

I have seen a book29 in Wilton library on hunting, hawking and heraldry, written in verse by Dame Juliana Berners, a nun from Henry VIII’s time, keen on field sports and fishing – who was perhaps the first woman to write a book in English. The book was printed in the time of Edward IV. Dame Juliana Berners says in her book that a hoby is a priest’s hawk and a merlin is a lady’s hawk, so it seems that in those olden days priests and ladies kept hawks too. When my father and I go hawking together his birds land on my gloved and outstretched arm.

. . .

I wander in the parklands at Wilton, imagining myself in Sidney’s Arcadia. I have fallen in love with the house, the grounds, and the beautiful old paintings in the long gallery. I have been shown them so many times by old servants and friends of this noble family that I am a good nomenclator of these pictures – I could make a portrait in words to set alongside each of them.

Here is the 1st Earl of Pembroke30, William Herbert.

The last time I was staying with my grandmother near Bristol, she told me the story of black Will Herbert, who was a mad fighting young fellow. Once when he was arrested in Bristol he killed one of the sheriffs, then escaped via Back Street, through the great gate into the marsh, and so to France. Afterwards, the city gate was walled up, leaving just a little door and turnstile for foot passengers. Will Herbert joined the army in France, and fought so well that favours were heaped on him. At the dissolution of the monasteries, Henry VIII gave him Wilton and its surrounding lands. He was much envied: a stranger and an upstart in our county. Toward the end of his life, he had a little reddish picked-nose dog (not of the prettiest), which loved him; when the Earl died, the dog would not leave his body, but pined away, starving himself to death. There is a picture of the dog in the gallery at Wilton that hangs below the picture of Will.

Here is Mary, Countess of Pembroke31.

She was Sir Philip Sidney’s sister; married to Henry, the eldest son of Will Herbert, Earl of Pembroke. That subtle old Earl predicted that his witty daughter-in-law would horn his son, told him so, and advised him to keep her in the country and not to let her frequent the court. She had a pretty sharp-oval face. Her hair was of a reddish yellow. She was very salacious. For example: each spring, she had the stallions brought close to a part of the house where she had a special place to stand and watch them mounting their mares. She had many lovers who mounted her, including Cecil, the crooked-back Earl of Salisbury. This is her epitaph:

Underneath this sable hearse

Lies the subject of all verse:

Sydney’s sister, Pembroke’s mother.

Death! Ere thou kill’st such another

Faire and wise and learn’d as she,

Time will throw a dart at thee.

Here is Sir Philip Sidney32, Mary’s brother.

Not only an excellent wit, but extremely beautiful, he is said to have much resembled his sister. His hair was not red; it was a dark amber colour. Perhaps it was not masculine enough; and yet he was a person of great courage. He was the reviver of poetry in those dark times. He bought Queen Elizabeth a bejewelled whip as a sign of his submission (which she had come to doubt).

In one of the pictures of Sir Philip Sidney are these verses:

Who gives himselfe may well his picture give,

Els were it vain, since both short time doe live.

In Mary’s time, Wilton was like a college: full of learned, scholarly people. She collected the library. She was a great chemist and set up a laboratory alongside the library. She talked of her experiments with her brother, and he in turn described them to Dr Dee. Philip dedicated his Arcadia to her, declaring: ‘Now it is done only for you, only to you.’ They loved each other so much that people wondered if they slept together. These siblings, one auburn-headed, the other amber, who live so vividly in my imagination, are not even ghosts in the garden now; or if they are, I cannot see them. I walked sombrely on the terraces at dusk this evening, trying to catch sight of them. But they are gone, and their fair bodies laid to rest: hers (I think) in Salisbury Cathedral beside her first husband, Henry, Earl of Pembroke; and his in St Paul’s. I shudder to think of it:

England, Netherlands, the Heavens and the Arts

Of . . . Sydney hath made . . . parts;

. . . for who could suppose,

That one heap of stones could Sydney enclose.

. . .

The situation of Wilton House33 is incomparably noble. King Charles loves it above all places and comes here every summer. He prompted the present Earl, Philip, 4th Earl of Pembroke, to make the magnificent garden and grotto, and to extend the side of the house that fronts the garden, with two stately pavilions at each end, all ‘al Italiano’. His Majesty intended to have his own architect, Mr Inigo Jones, do it. But Mr Jones was too busy with His Majesty’s buildings at Greenwich, so recommended another architect, Monsieur Solomon de Caus, a Gascoigne, who performed it very well; but not without the advice of Mr Jones.

There is a picture34 of King Charles at Wilton, which Sir Anthony Van Dyck copied from Whitehall. The King is on horseback, with his French riding master on foot, under an arch, all life-sized. Next to it is a picture of the famous white racehorse Peacock, also life-size and by Van Dyck.

Peacock has run35 the four-miles course in five minutes and a little more. He used to be owned by Sir Thomas Thynne of Longleat and valued at 1,000 li. Philip, Earl of Pembroke, gave 5 li. just to have a sight of him. Now, at last, his lordship owns him (I think he was given to his lordship as a gift). Peacock is a bastard barb. He is the most beautiful horse ever seen in this age, and is as fleet as he is handsome.

Philip, Earl of Pembroke, is a great patron to Van Dyck and has more of his paintings than anyone in the world.

. . .

I have been shown the armoury at Wilton. It is a very long room – full of weapons. The collection is as great as the manner in which it was obtained. During the Italian war, when Queen Mary was on the throne, there was a victory at the Battle of St Quentin, in Picardy, in 1557. At that battle, William, 1st Earl of Pembroke, was General, Sir George Penruddock of Compton Chamberlain was Major General, and my great-grandfather, William Aubrey, was Judge Advocate. The spoils collected were arms enough for sixteen thousand men on horse and foot.

. . .

On the south down of the farm at Broad Chalke, there is a little barrow called Gawen’s-barrow. I sit there sometimes, thinking of how the barrow must have been named for the Knight Gawain, nephew to King Arthur, whose exquisite manners are commemorated in Chaucer’s ‘Squire’s Tale’:

That Gawain with his old curteisye . . .

. . .

This autumn, Broad Chalke36 is sickly and feverish; I walked through the churchyard earlier today and saw three open graves.

. . .

My father has a pin, or web, in his eye, like a pearl, or a humour coming out of his head. The learned men of Salisbury could do him no good, but a good-wife of Broad Chalke, a poor woman named Holly, has cured him these past few days.

. . .

Mr Peyton is now37 vicar of Broad Chalke, and I have made friends with his wife’s brother, Theophilus Woodenoth, who was at Eton and then a scholar at King’s College, Cambridge, and is now come to stay at the vicarage. He talks to me about books, old English proverbs, and answers my questions about antiquities. He has advised me to read Lord Bacon’s essays, which I have found among my mother’s books. Mr Woodenoth is writing a book of his own, a little manual called Good Thoughts in Bad Times.

. . .

I am now a boarder at Blandford School in Dorsetshire: the most eminent school for the education of gentlemen in the West of England. Here books are covered with old parchments and leases, never with manuscripts, so far as I have seen. But there were no abbeys or convents for men in these parts before the Dissolution, so far fewer manuscripts flew around afterwards.

. . .

My health is improving. I am excelling at Latin and Greek: am the best among my peers. I have been lent a copy of Cooper’s Dictionary – Thesaurus Linguae Romanae et Britannicae, printed in London in 1584 and dedicated to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, and the Chancellor of Oxford – which is new to me. I am reading all the Terence parts first, then will move on to Cicero.

Reading Ovid’s Metamorphoses, translated into English by Sandys, leads me to understand the Latin better and is a wonderful help to my imagination.

I find Tully’s Offices too dry.

I prefer Lord Bacon’s Essays for an introduction to morals, excellences of style, hints and transitions. My mother has told me that Lord Bacon used to visit her kinsman, Sir John Danvers, at Chelsea and delight in his garden. Sir John helped Lord Bacon with his History of Henry VII, with more honesty and better judgement than any scholar.

Lord Bacon has argued38 that antiquities are ‘remnants of History, which have escaped the shipwreck of time’. I am drawn irresistibly to the past. Old objects and stories delight me.

. . .

I have found39 as much roguery at Blandford School as there is said to be at Newgate Prison. I know now the wickedness of boys. The ones who are stronger than me mock and abuse me, so I must make a friendship with one of them to protect me from the others.

. . .

A terrible day40. The master flexed his cane and looked away. I have seen it before: that hard look of anticipation, so deep, it is almost behind his eyes; the quick flick of his tongue across thin lips. It has happened before, happened so often already that I know there is nothing to hope for in catching his gaze or holding it. There is only endurance, and pain. He tells me to bare my buttocks and bend over the chair. I go to another place in my head: the bank of the brook at Easton Pierse, or the tree-lined riverbank at Broad Chalke, where I count the flowers and arrange their names in alphabetical order. I hear the cane hiss through the air, high above his head, before the burning begins, one stroke after another: hic, haec, hoc; hic, haec, hoc. The cane cuts as precisely as the Latin declensions. I do not, I will not, cry out. I am not in this scene; I am somewhere else, with the soothing sound of water running by. He beats me then about the head for insolence. Hic, haec, hoc: more brutal blows, less precisely aimed, but still the same rhythm. It is the grammar and rhetoric of violence. A language I will not learn, though the whole school seems to speak it. My face is running now with tears, blood and snot. Hic, haec, hoc; I wonder will my wits ever recover, or has something been smashed inside me that cannot be mended? My speech falters and my stammer will be worse in the morning. I will fall asleep thinking nothing.

. . .

Saturday. A play-day. Now that we are old enough, we boys are let out of school on Saturday afternoons to walk round Blandford in pairs, or larger groups. I have made friends with Sir Walter Raleigh41’s grand-nephews, Walter and Tom. I take them with me to visit old Mr Harding the glass painter’s workshop and furnaces again. I am fascinated by the ancient craft and by the furnaces. I like the gentleness of laying one thin coat of dilute colour across another, slowly and carefully, until the colour is perfect. Like a limner, or painter of manuscripts, a heavy hand makes the paint go on too thick, then it cracks and the effect is spoiled. This is how I would rather learn: slowly, gently. Inventive children (I know this is true of me) tend not to be tenacious. It is better to let the knowledge sink in slowly, calmly. If a child’s mind is parchment, or glass to be painted on, thick, vehement strokes – the harsh hic, haec, hoc of the master’s cane – will tear or smash it to pieces.

. . .

Sir Walter Raleigh is remembered with misgivings among our friends and neighbours in Easton Pierse because he all but ruined Sir Charles Snell by getting him to invest in the Angel Gabriel: a ship destined for Guyana. The ship cost Snell the manor of Yatton Keynell, the farm at Easton Pierse, Thornhill and the church lease of Bishop’s Canning. Raleigh’s grand-nephews are clever, proud, quarrelsome boys with tunable (but small) voices, who play their parts well on the viol. They tell me that their great-uncle had mapped out an apparatus for the second part of his History of the World, but when his publisher complained about the sales of the first part, he burnt it in disgruntlement, saying, ‘If I am not worthy of the world, the world is not worthy of my works.’ How I wish he had not done that! Now no one will know what would have been in the second volume of his book.

. . .

I have heard my grandfather42 Lyte say that Sir Walter Raleigh was the first to bring tobacco into England and make it the fashion. In north Wiltshire, my grandfather remembers a silver pipe being handed round the table from man to man. Ordinary people smoked through a walnut shell and straw. Tobacco was sold for its weight in silver, so when our old yeomen neighbours went to Malmesbury or Chippenham market, they kept their biggest shillings to place in the scales against the tobacco. Sir Walter Raleigh smoked a pipe of tobacco before he went to the scaffold. Some people thought this scandalous, but I think it was well and properly done to settle his spirits. My grandfather remembers when apothecaries sold sack in their shops.

. . .

Sometimes, on holy days43 or play-days, we boys go to tread the maze at Pimpherne, which is near Blandford.

. . .

Sauntering through Blandford44 today, dreaming of seeing the sea, the harbours and the rocks I have read about in books, I met a man weeping on the bowling green. He spoke English with a strong German accent. He sat upon the grass and rocked himself, like a nurse rocks an inconsolable infant. I sat down beside him and he told me he had been driven from his estate and country by the wars that rage there. Before the wars came, he had as good an estate as any Englishman. Now he is forced to maintain himself by surveying the land. He told me it is good to have a little learning for no one knows to what shifts and straits he might be brought. The German was not an old man, my father’s age, perhaps. I thought of Easton Pierse and the farm at Broad Chalke. I wondered how I would live, if I had to, without them, and in my mind’s eye I saw them suddenly ravaged by flames and blackened with soot. Would I earn my bread by painting then, or be employed to survey the land like this poor man?

. . .

Monday after Easter: my uncle Anthony Browne’s bay nag threw me today. She ran away with me and gave me a very dangerous fall. Just before, I had an impulse of the briar under which I rode that tickled the nag at the upper end of Bery Lane. Deo gratias!

. . .

On this day the King summoned Parliament for the first time since 1629.

. . .

The King dismissed Parliament after only three weeks.

. . .

The King recalled Parliament, hoping it would pass financial bills.

. . .

There was a debate in the newly convened Parliament in which preaching in support of absolute monarchy was attacked.

. . .

Fearing that he might be called to account for his argument that sovereignty must be absolute, Mr Hobbes has fled to France.

. . .

On this day Parliament passed the Dissolution Act. This means that the King can no longer rule without Parliament, which from henceforth must meet for a least one fifty-day session every three years.