MY FRIEND MR George Ent and I are travelling together. After a rough crossing, we landed at Calais.

We have been exchanging stories of our schooling. George Ent tells me he was once kicked by his schoolmaster down seven or eight flights of stairs, landing on his head. He was lucky not to break his neck! The day before, he had shaled one of his teeth, so he wrote to his father, Sir George Ent, to describe the treatment he had endured, enclosing the tooth and claiming he had lost it falling down the stairs. Sir George arrived the next day and took him away. Afterwards he went to my Trinity friend William Radford’s school at Richmond. William Radford is an honest sequestered gentleman and has become an excellent schoolmaster since he was excluded from his Oxford Fellowship by the Parliamentarian Visitors.

I intend to travel on to Orleans by way of Paris.

. . .

I have reached Paris1 and have a plan to see next the Loire, Brittany and the country around Geneva. I am staying with M de Houlle, in the churchyard of Saint-Julien-Le-Pauvre, at the sign of the golden rock, in front of the fountain of Saint-Séverin, near the Châtelet. I have written a letter to Mr Hobbes, who told me much about Paris before I came here.

. . .

The shopkeepers here2 in France count with counters, which is the best way. Counters were anciently used in England too.

. . .

I have reached Orleans, but here am suffering a terrible attack of piles.

. . .

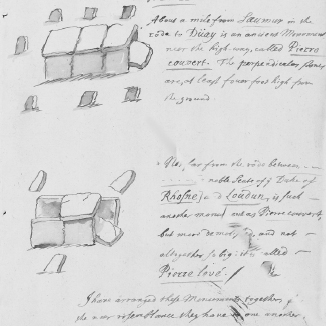

About a mile3 from Saumur on the road to Doué-la-Fontaine is an ancient monument near the highway called Pierre Couverte. The perpendicular stones are at least four foot high from the ground.

. . .

Not far from the road4 between the noble seat of the Duke of Rhône and Loudon is another monument like Pierre Couverte, but more demolished and not altogether so big. It is called Pierre Levée.

. . .

I have paid5 for my passage from Dieppe and will return to England.

. . .

I hear that Mr Hooke’s6 position as the Royal Society’s Curator of Experiments has been confirmed for life, and that he has been chosen as Professor of Geometry at Gresham College. This is excellent news, since his head lies much more to geometry than arithmetic.

I have seen Mr Hobbes7 and encouraged him to write about the Law. I said I think it a pity that he who has such a clear reason and working head has never taken into consideration the learning of the laws. At first he said he did not think he was likely to live long enough for such a difficult task – he is now seventy-six years – but I presented him with Lord Bacon’s Elements of the Law, to inspire him. He was pleased with the book and is reading it.

. . .

I have seen Mr Hobbes again and he showed me two clear paralogisms in Lord Bacon’s Elements of the Law, one of them on the second page, but whether or not he will write his own treatise on law I cannot tell.

Mr Hobbes always has8 very few books in his chamber. I have never seen more than half a dozen there when I visit him. Homer and Virgil are commonly on his table, sometimes Xenophon. He has described to me how he works. He sets about thinking and researching one thing at a time (sometimes for a week or fortnight). He rises about seven, has his breakfast of bread and butter, then takes a walk meditating until ten. In the afternoon he writes down his thoughts.

. . .

My friend Mr George Ent9, who is still in Paris, writes to say he might have found a suitable French-speaking boy servant for me named Robert, to replace the one I brought back from Paris myself, who is no good. He will send me a copy of Andrea Palladio’s I quattro libri dell’architettura (The Four Books of Architecture), which was first published in Venice in 1570, as soon as he can. Book I was published in English last year.

. . .

I have made a survey of Avebury with a plane table (helped exceedingly by my neighbour Sir James Long). The plane table provides a solid, level surface on which to make drawings.

. . .

I have written10 upon the spot about the stones at Avebury, because there is no way to retrieve their meaning except through comparative antiquities. History is good however made (Historia quoquo modo facta bona est). I have written, as I rode, at a gallop. I hope the faithfulness and novelty of my words will make some amends for any incorrectness in style.

The hinge for my discourse on Avebury is Mr Camden’s description of Kerrig y Druid (or Druid-Stones) in his Britannia, published in 1586. I wish I could journey to north Wales to see the stones Mr Camden writes about, and compare them with what I have seen and written about at Avebury.

The similarity between11 the name ‘Avebury’ – ‘Aubury’ (as it is written in the ledger book of Malmesbury Abbey) – and my own ‘Aubrey’ does not escape my notice. ‘Au’ or ‘Aub’ in old French means white and is a translation of the Latin albus. The whiteness of the soil about Avebury seems to countenance this etymology. But here in my mind’s eye I can see the reader of my diary smiling to himself, thinking how I have stretched the place name to be my own, not heeding that there is a letter’s difference, which quite alters the signification of the words. I see my reader’s scornful smile. I must obviate it with arguments from etymology. I hope no one could think me so vain! I have a conceit that ‘Aubury’ is a corruption of Albury (meaning old-bury, or the old borough).

. . .

I have made a close study12 of Walter Charleton’s Chorea Gigantum, or the Most Famous Antiquity of Great Britain, Vulgarly Called STONE-HENG, Standing on Salisbury Plain, Restored to the Danes, which was printed at the Anchor in the New Exchange last year (1663). He is mistaken in his claim that the stones are ‘unhewen as they came from the quarry’. They are hewn!

Mr Charleton claims13 that Stonehenge was built by the Danes as a court of election. He imagines that persons of honourable condition gave their votes in the election of their king, standing in a circle on the columns of stones. But this is a monstrous height for the grandees to stand! They would have needed to be very sober, have good heads, and not be vertiginous to stand on those upended stones! I cannot believe Mr Charleton is right.

. . .

I went back to Stanton Drew to see the stone monument there that I knew as a child. The stones stand in plough land. The corn was ripe and ready for harvest at this time of year, so I could not measure the stones properly as I wished. The villagers break them with sledges because they encumber their fertile land. The stones have been diminishing fast these past few years. I must stop this if I can.

The diameter of the stone circle is about ninety paces. I could not find any trench surrounding it, as at Avebury and Stonehenge.

. . .

Southward from Avebury14, in the ploughed field near Kynnet, stand three huge upright stones perpendicularly, like the stones at Avebury. They are called the Devil’s Coytes.

. . .

I have been to visit Mr Thomas Bushell at his house in Lambeth. He is about seventy now, but looks hardly sixty and is still a handsome proper gentleman. He has a perfect healthy constitution: fresh, ruddy face and hawk nose. He is a temperate man. He always had the art of running in debt, but money troubles oppress him now. He has never been repaid for the money he spent in the King’s cause during our late wars, and he has been in flight from his creditors ever since.

How well I remember15 my visit to his grotto at Enstone in 1643. I hear the Earl of Rochester has the statue of Neptune that used to be there now, and that he looks after it very well. I should ask old Jack Sydenham, who was once Mr Bushell’s servant, for the collection of remarks of several parts of England that Mr Bushell prepared. They may help my own collection.

. . .

The weather today has been terrible: very stormy.

I missed seeing16 my friend Mr Tyndale, who has been in London these past few days. He did not realise I was here until the day before he had to leave, and I was remiss in not contacting him. He had letters and a box to deliver to me, which he wishes me to pass on to his sister.

. . .

This Christmas I have seen again at Wilton, in Mr Hinton’s private garden, blossoms on the thorn bush that he grew from a bud of the Glastonbury Thorn, before it was cut down and burnt by Parliamentarian soldiers in the civil war.

Men say that the Glastonbury Thorn grew when Joseph of Arimathea visited Glastonbury with the Holy Grail and thrust his staff into Wearyall Hill. The tree flowered twice a year: in winter as well as in spring. Before it was destroyed, one of its budding branches was sent to the monarch each Christmas.

The bush in Mr Hinton’s garden17 gives out enough blossoms to fill a flowerpot, and I have sent some to my mother as a present. In this small way I keep memory of the ancient custom alive.

. . .

My horse almost killed me, and I have lacerated my testicle, which is likely to be fatal! My stammer has been terrible since.

. . .

My testicle is healing.

. . .

The widow of18 the Oxford mathematical instrument maker, Christopher Brookes, has given me a copy of the pamphlet he printed in 1649, ‘A new quadrant of more natural ease and manifold performance than any other heretofore extant’.

. . .

Looking on a serene sky19 this evening, I suddenly noticed a nubecula, much brighter than any part of the via lacteal, and about five times as big as Sirius. I shall show it to my neighbour Sir James Long tomorrow night. When the moon shines not too bright, it is very easily seen. It lies almost in the right line, between the bright star of the little dog and the constellation of Cancer.

Mr Samuel Pepys20, proposed at the last meeting, was unanimously elected and admitted as a Fellow of the Royal Society today.

. . .

Sir John Hoskyns21 has been offered some three or four of the late Mr William Dobson’s paintings for sale by Mr Gander, which he knows I might be interested in buying. One of them is of the clerk of the Oxford Parliament, good, but somewhat defaced. He says if I will pay 10 li. the portraits can be reserved for me until I go and see them and agree a price, or else have my deposit returned.

. . .

The poet Sir John Denham22 has married for the second time. His wife, Margaret Brookes, is a beautiful young lady, but Sir John is ancient and limping.

. . .

On this day England declared war on the Netherlands. The cause is mercantile competition.

. . .

I have been to see23 young Lord Rochester, currently imprisoned in the Tower, for attempting to abduct the heiress Elizabeth Malet. Sometimes his actions are extravagant, but he is generally civil enough. He reads all manner of books and is a wonderful satirist.

. . .

The Royal Society has suspended its Wednesday meetings because so many members have left London fearful of the plague.

. . .

Mr Wenceslaus Hollar24 has now finished engraving the portrait of Mr Hobbes I lent him. He has shown it to some of his acquaintances, and it is a very good likeness. The printer demurs at taking it, so Mr Hollar feels all his labour lies dead within him, but he has made a dozen copies for me.

. . .

There is plague in London.

In Mr Camden’s Britannia25 there is a remarkable astrological observation, namely, that when Saturn is in Capricornus, a great plague is a certainty in London. Mr Camden, who died in 1623, observed this in his own time, as had others before him. This year, 1665, Saturn is so positioned, as it was during the London plague of 1625.

. . .

I have made my first address to Joan Sumner, whom I hope I shall marry and thereby rescue my finances. She is thirty years old and comes from a family of clothiers who live near mine, at Sutton Benger and Seend, which are both close to Kington St Michael.

. . .

I am at Seend. I came here for the revel and to wait on Joan Sumner, hoping for marriage: our alliance will bring me the money I need to rescue my finances and her family will be glad of a connection to mine. Meanwhile, I have discovered chalybeate waters in her brother’s well: heavily impregnated with iron ore, and potentially of great medicinal value (more so, I suspect, even than the waters at Bath, which is only about ten miles away).

I discovered the waters26 when I was taking the air this afternoon, around 3 p.m. It had been raining all morning, until about 12 or 1 o’clock, so the sand had been washed away from the ore. By 3 p.m. the sun was out and I was surprised to see so many spangles in the light reflected by the clean ore. I examined some of the stones and went to talk to the smith in the town (George Newton), an ingenious man and clock-maker, who tells me he has melted some of this ore in his forge.

I sent my servant27 Robert Wiseman to Devizes for some powder of galles and when I infused a little in the ore-rich water, it immediately became as black as ink – so black that I could write visible letters with it. I have also tried evaporating it and it yields a sediment that is umber-like.

I have instructed my servant, ingenious Robert Wiseman, to try water from all the wells in the village with powder of galles.

. . .

Joan told me the story today of a poor pregnant woman who drowned herself in the River Avon. The body was brought into the church at Sutton Benger, where Joan saw it and noticed it seemed to be producing a cold sweat. She wiped the sweat away several times and pressed to have the body cut open to find out if the child was still alive inside.

. . .

Joan has given me a recipe to stop dogs barking which, she tells me, thieves used to use. It involves mixing boar’s fat and cumin seeds in a horn.

. . .

I am at Easton Pierse. I have finished transcribing Mr Pell’s Idea of Mathematics and will send it to Mr Boyle, who has been waiting for it. I have been so long perplexed with the unpleasant affairs of this earthen world that I have not been able to give as much time as I would like to the life of the mind. Mr Boyle has been expecting discoveries and fine things from me, but for now he will be sorely disappointed.

In about a month28, I hope to send him observations of my mysterious Turkey, or turquoise, ring, along with some other rustic observations I have been collecting. My collections are various. I do not disdain to learn from ignorant old women.

. . .

Meetings of the Royal Society at Gresham College had ceased until recently on account of the plague sweeping over London, but they have been resumed.

. . .

I have taken out a licence at Salisbury for my marriage to Joan.

. . .

Mr Faithorne is drawing my portrait in graphite and chalk. I cannot say if it makes me look younger than my forty years, but my clothes at least are elegant.

. . .

My good friend and fellow antiquary Mr Elias Ashmole has at last finished cataloguing the Bodleian Library’s collection of Roman coins – a very laborious task, which he began in 1658 at the request of the Bodleian librarian Mr Thomas Barlowe.

. . .

I have shown29 my mysterious ring to Mr Boyle and told him how I have observed over many months that the cloudy spots in the stone move very slowly from one side to the other. He asked if he could borrow the ring so he can observe it himself. I readily assented. A young man in his employment will make careful drawings of the spots in the ring every two or three weeks. Afterwards it will be possible to compare the drawings and indisputably observe the motion of the spots. Mr Boyle says he has heard that a turquoise stone may lose its lustre upon the sickness or death of the person that wears it. He is reluctant to admit strange things as truth, but not forward in rejecting them as possibilities.

I promised Mr Boyle that I would make careful observations of another stone, an agate, which belongs to a friend of mine. The agate has a cloudy spot in it that seems to move from one side to another. Mr Boyle is collecting observations of this kind.

. . .

All my business and affairs are suddenly running kim kam! There are treacheries and enmities in abundance against me. Joan Sumner is now claiming that she never agreed to marry me. She complains that I have claimed to be richer than I am and accuses me of concealing the fact that there is a mortgage on my house at Easton Pierse. My mother and I had hoped to borrow 100 li. from her, but that will not be possible now, and who knows what worse will befall. Joan says she will pursue me through the courts. She imagines I have conspired to defraud her of her dowry. But I was willing to settle my beloved Easton Pierse on her and any sons we might have brought into the world. She was to bring 2,000 li. as her portion to the marriage. Our settlement was sealed and I sincerely expected our marriage to be solemnised soon after.

. . .

General Monck, now General at Sea, has set sail against the Dutch.

. . .

Fire has blazed in London for four days: the part of the city inside the old Roman wall is charred and ruined. Fortunately, the Great Conflagration did not reach Westminster or the King’s palace in Whitehall, but thousands of people have lost their homes. They roam the streets like beggars.

. . .

Mr Hobbes is disturbed30 because he has learnt that some of the bishops have moved in Parliament to have him burnt as a heretic. He tells me he has burnt some of his papers.

The Parliamentary Committee31 is considering a ‘Bill against Atheism Prophaneness and Swearing’. It has been empowered to consider books that tend against the ‘Essence or Attributes of God’, and in particular Mr Hobbes’s Leviathan.

. . .

Following the Great Conflagration32, the City of London must be rebuilt. Mr Hooke has been chosen as one of the two surveyors of the City. The other is the glass painter Mr John Oliver. Since the Guild Hall is in ruins from the fire, the city’s officials and clerks have moved to Gresham College. This means the Royal Society can no longer meet at Gresham College every Wednesday. We will meet instead at Arundel House in the Strand, the home of Lord Henry Howard.

At a meeting of the Royal Society, Mr Oldenburg, Lord Henry Howard and others reported on their visits to the ruins of St Paul’s to see the preserved body of Bishop Braybrook, the Bishop of London, who died in 1404. The Bishop’s body, like many others, has been disturbed by the Great Conflagration: when the roof of St Paul’s fell in, the lead coffins below fell through the floor and broke open. Workmen clearing the rubble have put the bodies in the Convocation House and are charging people twopence a person to view them. I will go myself.

. . .

I saw Bishop Braybrook’s body33. It was like a preserved fish: uncorrupted except for the ears and pudenda, or genitals. It was dry and stiff and would stand on end. It was never embalmed. His belly and stomach were untouched, except for a hole on one side made by the falling debris. I could put my hand in the hole and could see his dried lungs.

I could not find Sir Philip Sidney’s body. It was buried somewhere without regard and his coffin sold for rubbish.

. . .

I spoke to some34 of the labourers clearing the rubbish in St Faith’s Church, which was ruined by the collapse of St Paul’s. They tell me that when they took up the leaden coffin of William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, whose sumptuous monument was among those tumbled into the church, the stink was so great that they took a week to scour themselves of it.

. . .

A little before35 the Great Conflagration, somebody made a hole in the lead coffin of Dean Colet, which lay above the ground beneath his statue. I remember my friend Mr Wylde and Ralph Greatrex, the mathematical instrument maker, decided to probe the Dean’s body through the hole with a piece of iron curtain rod that happened to be near by. They found the body lay in liquor, like boiled brawn. The liquor was clear and insipid: they both tasted it. Mr Wylde said it had something of the taste of iron, but that might have been on account of the iron rod. This was a strange and rare way of conserving a corpse. Perhaps it was a pickle, as for beef. There was no ill smell.

. . .

At a meeting of the Royal Society I volunteered to recommend the observation of tides to the Deputy Governor of Chepstow in Monmouthshire. The Society’s secretary will procure the printed papers with the relevant enquiries and tables. Sir Robert Moray then proposed that directions for seamen and enquiries about tides be separately printed, and the instruments mentioned in the printed papers be made available, at the Society’s expense. He hopes to obtain an order from the Duke of York to Trinity House, which has care of maintaining lighthouses and other aids to navigation in British waters, to ensure that the captain of every ship takes with him on his voyages a copy of this book, and makes observations accordingly and notes them down in a journal. Upon return, a copy of the captain’s journal should be given to Trinity House and to the Royal Society. The Fellows approved these proposals.

Mr Hoskyns then suggested that it would be a good idea to include in the printed book an instruction to the captain to fetch up different sorts of earth from the bottom of the sea. Mr Hooke is considering the design of an instrument that would be easy to use for this purpose.

Lord Henry Howard36 intends to bring before the Royal Society his account of the management of agriculture in Surrey and Berkshire.

. . .

I have been chosen37 by ballot (along with four other Fellows) to serve on the committee that examines and audits the Royal Society’s accounts. The others are Dr Christopher Merret, Mr William Harrington, Dr Walter Pope and Mr John King. We meet next Wednesday at Dr Pope’s lodgings before the next meeting of the Society.

. . .

Blood has been moved38 between two dogs for the first time. Before the Society, Mr King and Mr Thomas Coxe successfully performed the experiment on a small bulldog and a spaniel. The bulldog bled to death as its blood was transferred into the spaniel, which emitted as much of its own blood as was needed to make room for that of the bulldog.

No one takes any notice now of the fact that Mr Potter first thought of moving blood between animals. He and I tried it on chickens sixteen years ago: if only we had succeeded.

. . .

The band of my turquoise ring39 has broken. I fear that if I have the stone set again, the heat will destroy its peculiarity. I have told Mr Boyle I am unwilling to have it meddled with.

. . .

Today at the Royal Society I was given the printed enquiries (from nos. 17 and 18 of the Philosophical Transactions) on the observations of tides, which I will now take to the Deputy Governor of Chepstow.

In the Great Conflagration, all the unsold copies of the Philosophical Transactions were burnt in St Faith’s Church, near St Paul’s, where they were being stored. The booksellers in St Paul’s Churchyard lost their stock of books too. After the fire, volume no. 17 of the Philosophical Transactions was printed free of charge, and no. 18 was printed in Duck Lane.

At the meeting today40, I was also given a grain of wheat, taken from a batch produced in Surrey, said to shoot up like a rush, not a hollow straw. I am one of five Fellows involved in this plant trial. We will all plant our grains of wheat and compare our results.

. . .

At the Royal Society’s41 anniversary election meeting, we presented our report as examiners of the Society’s accounts.

My lord Brouncker42, Mr Wylde, Dr Charleton and I rode in a coach together on our way to the meeting at Gresham College. At the corner of Holborn Bridge, we saw a cellar of coals that had been opened by the labourers (who are digging the rubbish and new foundations of the city). The coals were burning and had been burning ever since the Great Conflagration.

. . .

Lady Denham died43 on the 6th of this month; it is rumoured that she was murdered by means of poison in her cup of chocolate. After her marriage to Sir John two years ago, the Duke of York fell deeply in love with her, which occasioned a distemper of madness in Sir John. This madness first appeared when he went from London to see the famous freestone quarries at Portland in Dorset, but when he got within a mile of his destination, turned back to London again and he did not see them. He went to Hounslow and demanded rents of lands he had sold years ago. He went to the King and told him he was the Holy Ghost. There are others at court who might have poisoned Lady Denham’s drinking chocolate. Some think the Duchess of York did it out of jealousy, but others think it was the Countess of Rochester. Lady Denham had no children.

. . .

My friend Edward Davenant44 has written to tell me that he has now given up his mathematical studies because his age is calling him to serious thoughts of another world. He is seventy-one this year. I am hoping to get him to print his work, lest it be lost, and have introduced him to John Collins of the Royal Society who may help him in this.

. . .

Since the Great Conflagration45 last year, all the ruins in London are overgrown with herbs, especially one with a yellow flower. On the south side of St Paul’s Church it grew as thick as could be, even on the very top of the tower. The herbalists call it Ericolevis Neapolitana: small bank cresses of Naples.

Many Roman remains46 have been discovered among the ruins of London. Christopher Wren, digging deep to lay the foundation of Bow church tower, came to the Roman way which now lies nineteen feet under Cheapside: they know it to be the Roman way by the gravel mixed with Roman brick-bats and potsherds and baked earth such as urns. Dr Wren believes it firm enough to act as the foundation of the tower.

At the Royal Society, before a large audience, we tested bottles of water I had carried up from Seend. It did not turn black, after so long a journey, but went a deep dark claret colour. The physicians present were all wonderfully surprised and urged me to recommend the water to the doctors of Bath. They think that in the treatment of some ailments, it would be better to begin with the waters at Seend and end with those of Bath (and in other cases vice versa).

. . .

I have written to several doctors in Bath, but to no purpose. I have now discovered that what the London doctors told me is true: the Bath doctors are in agreement about the quality of the Seend water, but they do not care to have their customers leave Bath. I shall make known the discovery myself by inserting it into Mr William Lilly’s almanac.

. . .

Joan Sumner’s brother John tells me floods of people have started coming to Seend to take the waters I discovered there. The village cannot accommodate them all, so there are plans to build new guesthouses before next summer. Sumner (whose well is the best) hopes the trade will be worth 200 li. per annum to him.

My discovery has been mentioned by Dr Nehemiah Grew in his History of the Repository of the Royal Society. There is iron ore in the water, which was not noticed before.

. . .

On this day the Treaty of Breda has secured peace between England and the Netherlands.

. . .

I have promised47 my old friend Mr Hobbes that I will publish his life: nobody else knows so many particulars of his life as I do. I have known him since I was eight years old. If it please God that I prosper in the world, I will arrange for an exact map of Malmesbury, showing the place of Mr Hobbes’s birth. I would have Mr Hollar draw a map of the town with the names of the rivers that embrace it – the Avon and Newnton Water – together with the prospect, the abbey church and King Athelstan’s monument. In the abbey church, where the choir was, now grass grows, where anciently were buried kings and great men.

. . .

In Oxford, I browsed the booksellers’ stalls, including Edward Forest’s, opposite All Souls College. Afterwards I met Anthony Wood: the younger brother of my deceased Trinity College friend Ned Wood. We drank at Mother Web’s and in the Mermaid Tavern, where Mr Wood spent 3s. 8d. He aims to be a despiser of riches, to live independently and frugally, and not to be afraid to die. His income is around 40 li. per annum. He supplements this by cataloguing libraries and occasionally selling a manuscript. He is at work on an historical survey of the city of Oxford, including its university, colleges, monasteries and parish churches. I offered to assist him with his researches.

We talked of Mr Hobbes48, my honoured friend, whose life I have promised to write. And we talked of poor Ned. It is already twelve years since he died of consumption: he was a promising scholar and had been elected a proctor of the University just weeks before his death. His brother is lastingly proud of the fact that Ned was freely elected, not imposed on the University by the Parliamentarian Visitor. He has edited five of Ned’s sermons.

Mr Wood was in the Bodleian quad last year when, by order of the King, John Milton’s works were burnt because they defended the execution of the late King. Mr Wood tells me he saw scholars of all degrees and qualities standing around the flames and humming while the books were burning.

He recently met and became friends with Mr William Dugdale, at work in the records in the Tower of London, gathering material for a third volume of his Monasticon. Mr Wood has promised to send Mr Dugdale documents to help him.

This summer, Mr Wood49 has been perusing the rent rolls, etc. in Christ Church treasury. He says there are many evidences there that belonged to Osney Abbey and innumerable writings and rolls which belonged to the priories and nunneries that Cardinal Wolsey dissolved when he set about founding his college in Oxford. But the Cardinal died before the task was completed, so the lands of the dissolved religious houses came under the King’s protection. He gave much away before the college was finally settled three years later in 1532; and for this reason, Christ Church cares little for those ancient documents that lie around in the damp and at the mercy of the rats. I will share with Mr Wood my own notes on the history of Christ Church, Trinity College and Osney Abbey.

I do not remember such hot weather as we have had this summer. Mr Wood says Oxford saw no rain from 30 June to 27 July, and none after that until 9 August. Several scholars have gone mad with heat and strong drink.

. . .

I have received50 a letter from Mr Wood in Oxford, asking me for details of Dr John Hoskyns’s time at New College – his birth, death, burial and the books he wrote – and for some details of other Oxford men including John Owen, the epigrammatist, and Sir Kenelm Digby. But I am leaving for London and am too plagued by my lawsuit to reply.

. . .

At a meeting51 of the Royal Society today, I was delighted to present Mr Francis Potter’s device for measuring time through an air-strainer. Mr Potter’s clock is powered by bellows, not cogs. Mr Hooke has been asked to consider and comment on it at a subsequent meeting. Mr Wylde said he had heard of a similar approach to measuring time (from Sir Edward Lake, via Mr Smethwick). We are both to present the Society with descriptions of these instruments.

. . .

Today, before the Royal Society52, Mr Hooke reported on the method for measuring time through air that Mr Wylde and I introduced at the last meeting. He said that though the invention is ingenious and new, it will not be suitable for pocket watches, nor as accurate and useful as the pendulum. The obstacle, in his view, is the unevenness of air, caused by the various degrees of its rarefaction and condensation, as well as its dryness and moisture.

. . .

I was arrested in Chancery Lane at Mrs Joan Sumner’s suit. I have been released, but there will be a trial at Sarum between us this coming year. How much I regret that I ever involved myself with that woman. I hoped she would restore my finances, but now she seems likely to ruin me.

. . .

I am at last53 within reach of leisure to assist Mr Wood. I will leave Broad Chalke and go to Oxford as soon as I can.

. . .

In Oxford, I have spent the evening with Mr Wood at the Crown Tavern. My French servant Robert Wiseman (Robinet Prudhomme) lit Mr Wood’s way home and was extravagantly rewarded with sixpence.

. . .

Early this morning my trial against Joan Sumner was heard at Sarum. I won and was awarded 600 li. damages, though there was devilish opposition against me. I fear this will not be the end of the matter, as Joan seems intent upon continuing to pursue me through the courts. I have discovered that I am not the only man she has treated thus. On 10 July 1665, a few months before I made my first address to her in an ill hour, there was a marriage licence taken out at Salisbury between Joan and one Samuel Gayford.

. . .

I read a paper on Wiltshire springs to the Royal Society.

I went today54 to Sir William Davenant the Poet Laureate’s funeral. He died two days ago. Mr Hobbes knew him well and they were in France together during the late wars. He wrote more than twenty plays, besides his Gondibert and Madagascar. His coffin was of walnut wood: Sir John Denham declared it the finest he has ever seen. Davenant’s body was carried in a hearse from the playhouse to Westminster Abbey, where he was received at the great West Door by the choir and choristers, who sang the church service: ‘I am the Resurrection’, etc. His grave is in the south cross aisle and on it is written (in imitation of Ben Jonson): ‘O rare Sir Will. Davenant.’

When Sir William Davenant became Poet Laureate in 1638, after Ben Jonson’s death in 1637, Thomas May was also a candidate.

Thomas May translated55 the poet Lucan’s Pharsalia (1626), which made him in love with the Roman republic. The odour stuck to him. His Breverie of the History of the Parliament of England was printed in 1650, the year he died from choking when tying his cap. Thomas May compared the Long Parliament to the history of Rome, even while admitting that the affairs of Rome were of such transcendent greatness that they admit of no comparison to states before or after. My friend Edmund Wylde knew Thomas May when he was young, and says he was thoroughly debauched, but I do not by any means take notice of this, for we have all been young. I must find out where his monument is.

. . .

I have seen Mr Hobbes56. He is writing a tract on the law of heresy.

. . .

The Council57 of the Royal Society has licensed the printing of John Wilkins’s Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language.

. . .

Today I brought before58 the Royal Society some mineral water from Milson in Wiltshire. Despite being carried eighty miles or so, the water kept its strength so well that when a little powder of galles was added to it and stirred in, the water became a dark red colour. The remainder of the water has been sent to Mr Merret for further examination.

. . .

I have decided59 to make a map of the remains of the Roman camps in Britain. Lord Bacon urged active men to become writers and after all the travelling that I have done on horseback through Wiltshire and south Wales, I am sure I can consider myself an active observer whose inspections of ancient monuments must be worth writing down. When I ride through the downs and see the numerous barrows – those beds of honour where now so many heroes lie buried in oblivion – they speak to me of the death and slaughter that once raged upon this soil, where so many thousands fell in terrible battles. I will trace the route the victorious Roman eagle took through ancient Britain and map the sites of those Imperial camps, now given over to sheep and the plough.

. . .

Exploring the sky60 with a telescope I noticed a cloudy star, which appeared to be about the size of Venus and resembled a dim planet, lying in a right line and near the midway between Cancer and the Head of Hydra.

. . .

The Royal Society61 has established a committee to examine, consider and report on Mr Wilkins’s Essay Towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language, published this year. A Real Character, as opposed to a notional, nominal or verbal one, has a shape that embodies the structure of the language, lexically, grammatically, or both. Mr Wilkins is developing ideas about Real Characters in Lord Bacon’s Of the Advancement and Proficience of Learning, which was translated from Latin into English in 1640.

. . .

When I was a boy62, I used to hear from my grandmother the story of how Queen Elizabeth loved my great-grandfather, Dr William Aubrey, even though he voted against the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Mr Wood has asked me to help him by consulting Thuanus’s Annals for honourable mention of my great-grandfather Dr William Aubrey, who is also mentioned in the Life of Mary, Queen of Scots. Thuanus was a president of the Parlement of Paris and the author of a history of his own times from 1546 to 1608.

. . .

I have a mind to make a kind of pilgrimage this summer to see some Druidish monuments in Caernarvonshire, and will go via Weston on my way. The Royal Society has requested that Mr Wood make a list of all the treatises that Lord Bacon wrote.

I have been told63 that in the library of the Royal Society there is a book that would be of help to Mr Wood in compiling his history of Oxford, it being a collection of several writers of both universities and of the nation.

. . .

By malicious contrivance I was arrested today, in connection with my proposed marriage to Mrs Joan Sumner, but was retained for less than two hours. I was meant to go to Winton for a retrial tomorrow, but the date has been put back now.

. . .

My servant Robert64 hopes to get employment in Oxford: it is the place he loves and he hopes to make a better livelihood there than I can now offer him in my straitened and beleaguered circumstances. I hope Mr Wood will help him when opportunity arises.

. . .

My lawsuit continues, to my great dismay and financial ruin.

I am collecting my letters from The Lamb in Katherine Street in Salisbury.

. . .

I have been to see65 the Coway Stakes in the Thames, opposite Cowe-way, on the right bank of the river between Sunbury and Shepperton. It is said this is the place where Julius Caesar crossed the river. According to the local people, three of the stakes are visible on a clear day when the water is low. Venerable Bede says the stakes could be seen in his day (at least 500 years ago). The fishermen still avoid casting their nets here. But this summer the Lord Mayor’s Water Ballif had one of the stakes taken up because it hindered the barges and was likely to split them. If I can I will ask the Water Ballif for a sight of this antiquity.

. . .

As soon as my lawsuit66 will give me leave, I will lengthen my life a little by reviving my spirit in Oxford. Joan Sumner is an unusually litigious woman: she insists I intended to defraud her and is demanding a retrial, but my defence is that I was sincerely prepared to marry her and still am, despite all the legal troubles she has brought down upon my head.

. . .

The great poet67 Dr Abraham Cowley died at the end of July last year (1667). His will is a testament to true and lasting charity. He has settled his estate so that so much every year is to be paid for poor prisoners cast into gaol by cruel creditors for some debt or other. I have been told this by Mr Dunning of London, a scrivener who is acquainted with Dr Cowley’s brother. I do not think this benefaction is mentioned in the Life of Cowley that has been printed along with his collected works this year. It is certainly the best method of charity.

Sir John Denham has written some excellent verses on the death of Abraham Cowley (which prove that Sir John has fully recovered his wits since the fit of madness that overcame him before his wife died):

His fancy and his judgement such,

Each to the other seemed too much:

His severe judgement giving law,

His modest fancy kept in awe;

As rigid husbands jealous are,

When they believe their wives too fair.

. . .

St Paul’s Day68: I hope Mr Wenceslaus Hollar will make more etchings of my several prospects of Osney Abbey. I fear that the one he made for Mr Dugdale’s book might have melted in the Great Conflagration. Mr Hollar is expected back in England around Candlemas. He has gone on a journey to Tangier with Lord Henry Howard, grandson of the Earl of Arundel, to negotiate with Moulay Al Rashid, the Moroccan Sultan. Mr Hollar, who is His Majesty’s Designer, will make drawings to show the King what his most remote colony looks like.

. . .

If Mr Wood needs69 any records at Rome searched, I think I can arrange this for him through the Jesuits I met in Paris. One of them has suggested to me that Mr Wood should first print his book in English, not Latin, because it will become more famous and sell better that way.

. . .

I brought my drawing70 of the cloudy star I discovered last year before the Royal Society and it was entered into the Register Book.

. . .

Early this morning, between eight and nine o’clock, my retrial was heard at Winton. With much ado I got a verdict of damages of 300 li. in my favour. This is half the amount I was awarded in my first trial at Sarum, but it is still something to set against what I must now pay my lawyer.

. . .

Sir John Denham71 was buried today in Westminster Abbey, in the south cross aisle, near Sir Geoffrey Chaucer’s monument.

. . .

Because of my financial troubles, I am in as much affliction as a mortal can be, and it seems I will never be at peace until all has been lost and I wholly cast myself on God’s Providence.

. . .

Today, I brought before72 the Royal Society Mr Potter’s account of his experiments in moving blood between animals, which he wrote in 1652, to try and establish that he was the first to attempt this experiment. I helped him with an experiment to move blood between chickens as early as 1649.

. . .

In Mr Samuel Cooper’s studio73, which I visited today, I had an interesting conversation with Dr Hugh Crescy of Merton College, a great acquaintance of Lord Lucius Cary, Viscount Falkland. Dr Crescy says he was the first to bring Socinus’s books into England, and Lord Cary borrowed them from him soon afterwards. Before the civil war, Lord Cary lived at Tew, about twelve miles from Oxford, and the best wits of the University visited him there, so his house, in that peaceable time, was like a college, full of learned men, including my great friend Mr Hobbes. I have heard Mr Hobbes say that Lord Cary was like a lusty fighting fellow that drove his enemies before him, but would often give his own party smart back-blows.

Lord Cary adhered74 to the King when the civil wars began, and after the Battle of Edgehill he became Principal Secretary of State, together with Sir Edward Nicholas. Lord Cary died in 1643 at the Battle of Newbury, where he rode in between the two armies – the Parliament’s army and the King’s – like a madman, just as they were starting to engage. And so he threw his life away. Some say this was because he had given the King bad advice, but others say it was because his mistress at court, whom he loved above all creatures, had recently died, and this was the secret cause of him being so madly guilty of his own death.

. . .

I have sent75 Mr Edward Davenant Euclid’s Data. Lately he has been working very hard at mathematics, especially on the problem of the doubling of the cube geometrically. But now he tells me he is so oppressed by other business that he has little time to think about mathematics.

. . .

Mr Wood has quarrelled76 with his sister-in-law and been thrown out of the house where he was born opposite Merton College. He is also slowly becoming deaf, which makes him more melancholy and retired than ever.

. . .

I have now but one horse fit to be ridden, otherwise I would send one to Oxford for Mr Wood so that he might come to stay with me in Wiltshire.

. . .

The work of making77 the River Avon navigable from Salisbury to Christ Church has commenced. Seth Ward, Bishop of Salisbury, dug the first spit of earth, and pushed the first wheelbarrow. His lordship has given at least a hundred pounds of his own money to finance the digging.

. . .

Seth Ward tells me78 that at Silchester in Hampshire, which was once a Roman city, it is possible to discern in the ground where corn is now grown signs of the old streets, passages and hearths. He saw this with Dr Wilkins (now Bishop of Chester) in the spring.

. . .

This searching79 after antiquities is a wearisome business, yet nobody else will do it.

. . .

At Bemarton80, near Salisbury, is a paper mill, which is now over a hundred years old, and the first that was erected in the county of Wiltshire. The workmen there told me it was the second paper mill in England. I remember the paper mill at Longdeane, in the parish of Yatton Keynell, was built by Mr Wyld, a Bristol merchant, in 1635. It supplies Bristol with brown paper. No white paper is made in Wiltshire.

. . .

Mr Wood has been summoned81 by the Delegates of the University Press and told that they will give him 100 li. for his manuscript of The History and Antiquities of the University of Oxford, on the condition that he allows the book to be translated into Latin, under the supervision of Dr Fell, Dean of Christ Church. But I am certain it would bring more fame and sell better in English.

Dr Fell made another (more helpful) suggestion: that Mr Wood should begin to compile short biographies of all the writers and bishops who have attended Oxford University. I would be more than willing to help him in this.

A new idea82 for a treatise on education has come into my head.

. . .

I am in Broad Chalke83. Before I left London I left a cloak in the warehouse of the carrier Mr Wood uses. The carrier’s wife has since sent me a cloak, but it is a much shorter one, not mine. I hope Mr Wood can speak to the carrier’s wife about this for me, but I am sorry to trouble him about so mean a business. I am going to Easton Pierse next week.

. . .

I have heard84 that my Oxford tutor, Mr William Browne, has died, aged fifty-one or two. About eight years ago he was made vicar of Farnham in Surrey. He died of smallpox, infected by burying a corpse that had died of the disease.

. . .

I have presented85 the Royal Society with a portrait of Mr Hobbes by Jan Baptist Jaspers: an excellent painter and a good piece.

I was to see86 Mr James Harrington last Wednesday night, but he proved unable to meet me. He lives in the Little Ambry in a fair house on the left side, which looks into the Dean’s yard in Westminster. There is a pretty gallery in the upper storey where he commonly dines, meditates and takes his tobacco.

I have a short poem87 by Mr Harrington in his handwriting:

On the State of Nature

The state of Nature never was so raw

But oaks bore acorns and there was a law

By which the spider and the silk worm span;

Each creature had her birth right, & must man

Be illegitimate! Have no child’s part!

If reason had no wit, how came in Art?

He is wont to say, ‘Right reason in contemplation is virtue in action, et vice versa. To live according to nature is to live virtuously, but the Divines will not have it so.’ He also says that when the Divines would have us be an inch above virtue, we fall an ell (an arm’s length) below.

Mr Harrington suffers88 from the strangest sort of madness I have ever found in anyone. He imagines his perspiration turns to flies, or sometimes to bees. He has had a movable timber house built in Mr Hart’s garden (opposite St James’s Park), to try an experiment to prove this delusion. He turns the timber structure to face the sun, chases all the flies and bees out of it, or kills them, then shuts the windows tight. But inevitably he misses some concealed in crannies of the cloth hangings and when they show themselves he cries out, ‘Do not you see that these come from me?’ Aside from this, his discourse is rational.

. . .

My former servant89, Robert, sends word from Rome where he is accompanying his new master, having visited Florence and Pisa and expecting to proceed to Naples. He tells me that they have seen the great duke’s palace at Pisa, but not the jewels, and that the carnival is not taking place, as the Cardinals have not yet elected the new Pope. It is one of my most lasting sorrows that my mother interfered with my plans to visit Italy.

. . .

Easter Tuesday90. I must now take leave of my beloved Easton Pierse, where I first drew breath in my grandfather’s chamber. Cruel fate dictates that I cannot afford to keep the house in which I was born, the house that was my mother’s inheritance. Four years ago, before my troubles with Joan Sumner began, I had an income of around 700 li. per annum from my estates, and I went around in sparkish garb with a servant and two horses. Now all my estates will soon be sold, my servant is gone, and I live in happy delitescency, free from responsibilities.

. . .

Today I made sketches of the prospects of Easton Pierse: the trees and the thin blue landscape that surround this house I love. The prospect from Easton Pierse is the best between Marsfield and Burford, and though all along that ridge of hills between those two towns are lovely prospects, none has so many breaks and good ground objects as the prospect from Easton Pierse.

Many of the old ways91 are lost, but some vestigia are left. Anciently there was a way from the gate at the brook below my house to Yatton Keynell, and another by the pound and manor house, leading northwards to Leigh Delamere and southwards to Allington, but there is no sign of it left now.

I remember how my grandfather92 told me that back at the beginning of the century, the land from Easton Pierse to Yatton Keynell was common land and the inhabitants of Yatton and Easton put cattle on it equally. Likewise, the land between Kington St Michael and Draycot Cerne was common field, where the plough maintained a world of labouring people. In my time, much has been enclosed, and every year more and more is taken in. Enclosures are for the private, not the public good. After it has been enclosed, a lone shepherd and his dog or a milkmaid can manage the land that used to employ several score labourers when it was worked as ploughed land. Ever since the Reformation, when the enclosures began, these parts have swarmed with poor people.

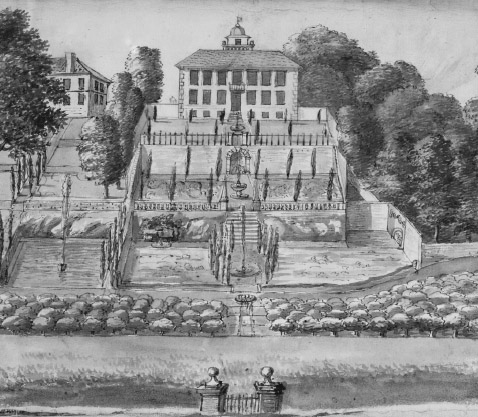

I have sketched my house at Easton Pierse and marked with a cross my grandfather’s chamber where I was born. If it had been my fate to be a wealthy man I would have rebuilt my house in the grandest of styles. I would have added formal gardens in the Italian mode of the kind I have seen at Sir John Danvers’s house in Chelsea and at his house in Lavington. It was Sir John who first taught us in England the way of Italian gardens. I would have erected a fountain like the one that I saw in Mr Bushell’s grotto at Enstone: Neptune standing on a scallop shell, his trident aimed at a rotating duck, perpetually chased by a spaniel. I would have carved my initials on a low curved bridge across the stream. I would have remade my beloved home in the shape of the most beautiful houses and gardens I have visited in my unsettled life, tumbling up and down in the world. But fate has taken me on a different path and the house of my dreams is mere fantasy: a pretty sketch on paper.

I have collected together93 my drawings of Easton Pierse, my beloved house and its prospects, and designed a grand title page: Designatio de Easton Piers, by the unfortunate John Aubrey! Alas, I fear I will soon be an exile! I am mindful of Ovid’s description of Daedalus, exiled on Crete: tactusque loci natalis amore (touched by love for his birthplace). I will make this one of the epigraphs for my book of drawings.

There is smallpox in Taunton again this year.

. . .

I saw Mr Wood today94 in London and told him the news that the Welsh antiquary Percy Enderbie, the author of Cambria Triumphans, died recently.

. . .

I am at Broad Chalke95. I have received the astrological chart of my birth from Mr Thomas Flatman and it reveals no end of trouble. He has made the figure of my nativity and found it agreeing with all the misfortunes of my life. Part of my unhappiness has proceeded from Venus, love, and love affairs, altogether ineffectual so far, together with Saturn in my house of marriage.

. . .

My former servant96, Robert, has left a hat and other keepsakes for me with Mr Browning’s maidservant. He has other items to present to me when I can pay him for his services.

. . .

As Ovid tells us, families, and also places, have their fatalities: Fors sua cuiq’loco est (Ovid, Fasti, Lib. iv).

. . .

This year, not far97 from Cirencester, there came an apparition, which when asked if it be a good spirit or bad, returned no answer, but disappeared with a curious perfume and most melodious twang. My friend Mr William Lilly believes it was a fairy.

. . .

Mr Lodwick, my friend98 and Mr Hooke’s, has sent me an essay he has written on the Universal Character, which continues the search for an artificial language he began as a young man when he published A Common Writing (1647) aged just twenty-seven. In his new essay Mr Lodwick seeks to describe all possible sounds using a new syllabic notation (vowels are expressed as diacritics). Possible sounds and their notations are presented in a table that allows certain syllables to be placed, even if they are not used in a particular language. In this way, he has invented a way of truly writing what is pronounced, or truly pronouncing what is written. Mr Lodwick claims his system is complete, rational and therefore universal. He hopes it will lead to the construction of a philosophical language.

. . .

I think I have now done about three quarters of my perambulation of Wiltshire. In the spring I hope I can do what remains to be done in two or three weeks. I must hope to do it invisibly to avoid arrest for my debts. I feel as though I am working under a divine impulse to complete this task: nobody else will do it, and when it is done no one hereabouts will value it: but I hope the next generation will be less brutish.

I have sought out the Roman, British and Danish camps and the highways. I have traced Offa’s Dyke from Severn to Dee and Wednesdyke and corrected Mr Camden’s Britannia in some places, and his claim as to where Boudicca’s last battle was. I surveyed the camps and found out the places of the battles by the barrows. Sir John Hoskyns and Dr Ball say this work is the best I have done: but it is dry meat.

Between south Wales99 and the French sea, I have taken account of the several kinds of earth and the natural observables in it, and the nature of the plants, cattle and people living off each respective soil.

When I was a boy100, my grandfather used to tell me the story of Mr Camden’s visit to the school at Yatton Keynell in the church there. Mr Camden took particular notice of a little painted glass window in the chancel, which has been dammed up with stones ever since I can remember, presumably to spare the parson the cost of glazing it.

Also in Yatton Keynell101, on the west side of the road, where it forms a ‘Y’ shape, there is a little close called Stone-edge. From this name, one might expect a stone monument, but if there was ever one there, time has defaced it. There is a great quarry of freestone nearby, which would be suitable for building such a monument. I am inclined to believe that in most counties of England there are, or have been, ruins of Druid temples.

Mr Samuel Butler102 told me that Mr Camden much studied the Welsh language and kept a Welsh servant to improve him in that language for the better understanding of our antiquities.

. . .

The Roman architecture flourished103 in Britain while the Roman government lasted, as appears by history, which makes mention of their stately temples, theatres, baths, etc., and Venerable Bede in his History tells us of a magnificent fountain built by the Romans at Carlisle in Scotland, that was remaining in his time. But time and northern incursions have left us only a few fragments of their grandeur. The excellent Roman architecture degenerated into what we call Gothic by the inundation of the Goths.

The Roman architecture came again104 into England with the Reformation. The first house then of that kind of building was Somerset House. Longleat in Wiltshire was built by Sir John Thynne, steward to the Duke of Somerset. The next house that I can find about London is the new Exchange, then the Banqueting House at Whitehall, by King James. In the time of King Charles I: Greenwich, Queenstreet, Lincoln Inn Fields. By now it has become the most common fashion.

. . .

Today I presented105 the Royal Society with an old printed book in the Ancient British language. It will be added to the Society’s library.

. . .

Today I gave106 two more books to the Royal Society: Grammatica Linguae: Cambro-Britanniae, by Dr Davies; and Heronis Ctesbii Belopoica: Telefactivia by Bernardinum Baldum.

I have also presented107 the Society with a piece of Roman antiquity: a pot that was found in Weekfield, in the parish of Hedington in Wiltshire in 1656. When it was found it was half full of Roman coins (silver and copper) from the time of Constantine. I explained to the learned Fellows that this was the site of a Roman colony and the foundations of many houses and much coin has been found there.

. . .

Since the Great Conflagration of London, many of the inscriptions in the city’s churches are not legible any more, but there is one for Inigo Jones that can still be read notwithstanding the fire. The inscription mentions that he built the banqueting house and portico at St Paul’s. Originally, there was a bust of Inigo Jones too, on top of this monument, but Mr Marshall in Fetter Lane took it away to his house (I must see it).

I am pleased to hear108 that Mr Payne Fisher has gone round transcribing as many of the London inscriptions that remain legible since the fire as he can find.

. . .

Glass is becoming109 more common in England. I remember that before the civil wars, ordinary poor people had none. But now the poorest people on alms have it. This year, between Gloucester and Worcester, three new houses with glass are being built. Soon it will be all over the country.

. . .

I have been helping110 Mr Wood in his biographical researches and have discovered that Christopher Wren has played a trick on us by making himself a year younger than he really is. He has no reason to be ashamed of his age, given that he has made such admirable use of his time.

I have introduced111 Mr Wood to Mr Ralph Sheldon, another esteemed antiquary, who has devoted himself to study since he was widowed in 1663. He has a fine library and a cabinet of curiosities in his house at Weston in Warwickshire, and has been working on a catalogue of the nobility of England since the Norman Conquest. He is a Roman Catholic.

. . .

My friend Walter Charleton112, physician to the present King and the late King, has warned me against too much credulity in astrology. He has fulfilled my request and sent me the double scheme of his unhappy nativity, which Lord Brouncker worked out for him. But he says he has no belief in astrology and does not believe his birth considerable enough to be registered by the stars. He has personal experience of the inaccuracy of Lord Brouncker’s predictions: and thus he hopes to divert me from the rock upon which he has been shipwrecked.

. . .

Surely my stars113 impelled me to be an antiquary. I have the strangest luck at it: things seem just to drop into my mouth, as though I were a baby bird.

. . .

I have now completed114 the sale of that most lovely seat, my beloved Easton Pierse. I handed over possession of it today, and the farmland at Broad Chalke. I have lost 500 li. + 200 li. + goods + timber. I am absconded as a banished man.

There are places unlucky to possessors. Easton Pierse has had six owners since the reign of Henry VII (I myself have played a role in this), and one part of it, called Lyte’s Kitchin, has been sold four times since 1630. The new owner is Mr Robert Sherwin.

It is certain that there are some houses lucky and some that are unlucky; for example, a handsome brick house on the south side of Clarkenwell churchyard has been so unlucky for at least these forty years that it is seldom tenanted; and now no one will venture to live there. Also a handsome house in Holbourne that looked into the fields: about six tenants, one after another, did not prosper there.

. . .

Would I find refuge from my troubles by entering a monastery?

Of late, I have begun to wish there had been no dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII and that his reformers had been more moderate. The Turks still have monasteries. Why were our reformers so severe? There should be receptacles and provision for contemplative men, if not five hundred at a time, at least one or two. I have been thinking recently what a pleasure it would have been to travel from monastery to monastery. In the Lutheran countries the reformers were more prudent: they did not destroy the monasteries, only altered the religion.

I leave the task of reconciling the differences of the Roman and English Churches to them that have nothing else to do and know not how to spend their pains better. For my part, after so many tossings and troubles in the world, I cannot think of a better place for a man to withdraw than that learned Society of Jesus where the Jesuits study what they have a mind to: music, heraldry, chemistry, etc. I have always reserved this as my ultimum refugium. I do not waste my time and thoughts on religious disagreements, but how I wish I could retire to a monastery to advance my work in peaceful surrounds.