ABOUT TWENTY YEARS ago1, I gave a quantity of petrified shells to the Royal Society. They were something like cockles, but plain and with a long neck rather than striated or invecked. I found them in south Wiltshire. Mr Hooke says the species is now lost. The quarry at Portland in Dorset is full of oyster shells, and a great deal of stuff like sugar candy, that Mr Hooke says is petrified seawater.

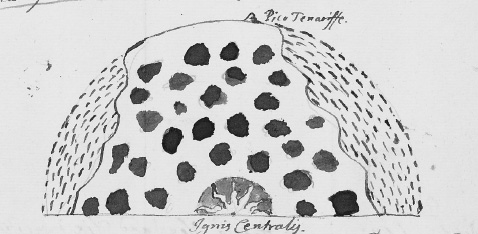

I have often thought2 that there was a time when the whole globe was covered with water, and that the world is like a pomegranate, full of caverns. Anyone who has seen the caves at Wookey Hole or the Peake in Derbyshire will have a strong and lively idea of what I mean. Perhaps earthquakes caused the water to sink and then the earth appeared. I am led to believe this by the great quantity of petrified fish shells that can be found on high hills.

I dined3 at Mr Hooke’s. He has finished his Atlas.

. . .

Today I helped carry4 the pall for the satirist Samuel Butler’s coffin. He died of consumption two days ago and we have buried him in the churchyard of Covent Garden, in the north part, next to the church at the east end. His feet touch the wall. His grave is two yards from the pilaster of the door and six foot deep. He printed a witty poem against religious fanatics, called Hudibras, in the early 1660s, which was extremely popular. He could have had preferments aplenty, but would not accept any good ones, so died in want.

. . .

Mr Hobbes’s short5 Life by himself in Latin will be printed next week, and Mr Wood shall receive six copies.

. . .

I am at Gresham6. Mr Pigott has written to tell me he intends to buy all the numbers of the Transactions of the Royal Society since no. 132 (1676), to complete the collection in their library at Wadham College. I reckon that since no. 132, there have been four by Mr Oldenburgh; six by Dr Grew; and two more by Mr Hooke; so twelve in total.

. . .

I have given7 the Royal Society a copy of the Life of Thomas Hobbes.

. . .

I am trying8 to find out whether the Ferraran library is at Ferrara, or Modena, and have written to Octavian Pulleyn, via contacts in Paris, to ask. All the princes of Italy are so careful to conserve their libraries and choice collections of manuscripts.

. . .

Mr Paschall has asked9 me if I can recommend any historical writers on the West Indies, particularly concerning what the Church of Rome has done in Peru and Mexico and the English Protestants in the northern tracts (Virginia and New England).

. . .

Today I have received10 an account of Ben Jonson’s life from Mr Isaac Walton (who also wrote John Donne’s life). Mr Walton is now eighty-seven years old. The account is in his own handwriting. I will send it on to Mr Wood for safe keeping.

. . .

Mr Wood has written11 to me to say that he is now back in Oxford and has leisure to read my Lives if I will send them to him. He encourages me to continue my collecting and researches and urges me to believe that these truly are my talents.

. . .

I went with Mr Hooke12 to Jonathan’s coffee house, where Mr Henshaw refused the suggestion that he become president of the Royal Society.

Israel Tonge was buried13 today in the vault of the churchyard of St Mary Staining, where there was a church before the Great Conflagration, of which he was parson. He excelled at alchemy. He also set up an excellent school following the Jesuits’ method of teaching at Durham in 1658 or 1659. Afterwards he taught in Islington at Sir Thomas Fisher’s house. I went to see him there in the long gallery where he had put up several printed heads of Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Hannibal, Scipio, Aristotle, Archimedes, etc. with different declensions of verbs under them (the dative under one, the ablative under another, etc.). Then when the boys come to a verb that governs an ablative case, for example, it presently occurs to their memories: ‘Oh, this verb is under Julius Caesar’s head’, etc. This way of local memory makes a fast impression or idea in their tender memories.

. . .

Dr Pell has returned my book, but without any corrections or suggestions for improvements. Poor man! He is old and disconsolate, living in poverty. Soon I will send my remarks on 120 Lives to Mr Wood in Oxford. I ought to work some more on them first, but am distracted into reading French romances. I need to rub up my French, which has gone rusty with disuse.

. . .

Dr Blackbourne and I14 have published the ‘Vitae Hobbianae auctarium’ with Hobbes’s accounts of his own Life. Mr Wood has been a great help to me in this. Dr Blackbourne is a young man of prodigious parts but ungovernable: he does not use me well in losing my papers. The mischief of it is that the great concern of the present politics drowns and takes away the venom of my sting as to the Right Reverend Fell. The felonies of the Reverend Fell seem insignificant amidst the present troubles. A pox take plots and plotters!

Quaere: what do the academics say at the coffee shops about Mr Hobbes’s life?

. . .

On this day the King dissolved the Parliament. He refuses to compromise on the succession. The Whig, or Country, Party hopes to exclude the Roman Catholic James, Duke of York, but the King will not have it. A new Parliament will meet in Oxford in March. These turmoils remind me of my undergraduate days: God grant us peace!

. . .

Mr Dugdale has printed15 his Short View of the Late Troubles, which draws on the newsbooks that grew up during those years of civil war. He says in his preface that he has delivered in his own words what he knows, but for that which is beyond his own knowledge he has relied on other authors and the common Mercuries and other public licensed narratives of the events of the civil war.

. . .

The Earl of Berkshire16 has thanked me for my account of the waters of Leek and encouraged me to do some further experiments on their nature. He has left 10 li. for me at a draper’s in St Paul’s Churchyard and entreats me to accept it.

. . .

The King has dissolved17 Parliament again. He convened it at Oxford on 21 March and it lasted just eight days. Now he will rule without a Parliament and it is rumoured another Popish plot is afoot. My friend George Ent was wont to say, ‘A pox take Parties!’, and I say, ‘A pox take plotters!’

. . .

I intend to send18 my Book of Lives to Mr Wood next week, but I cannot think how to do this safely, since if it gets lost there will be no retrieving it. I could take it myself and go and see my friend Sir James Long too, but Oxford is once again crammed to bursting point and I do not intend to end up sleeping by a fireside at my age.

How much work I would get done if I did not sit up with Mr Wylde until one or two in the morning, or if there was someone to get me up in the mornings with a good scourge! I think I could finish my Lives in a week, if I were to stop wasting time. Sir James Long has invited me to stay again.

I intended to take19 down Sir Jonas Moore’s memories, of the mathematician William Gascoigne especially, from whom he received most of his knowledge, but I delayed doing so, and now death has taken Sir Jonas away. I must set down what I can remember of what he used to say. Also, I remember that I did not take the measurements of Silbury Hill for my Monumenta Britannica because Sir Jonas had promised to give them to me. He had taken them accurately for the ordnance. I must find the measurements among his papers if I can.

Next week I will buckle to finish my Lives. I am sure I could do it in a week.

. . .

When I sent20 my small offering of books to the Bodleian Library in 1675, George Ent added to their number to make it up to a large enough donation for recording in the Benefactors’ Book. He put in The Mystery of Jesuitism, or Jesuit Morals, I forget which. Now I have never meddled with controversy in my life, nor shall I ever! I am only for mathematics, philosophy and antiquities. It is for my gift of the Historia Roffensia manuscript that I should be remembered. But now I have fears I will be caught up in the religious strife on account of the book George Ent gave to the Bodleian Library on my behalf.

. . .

Mr Paschall has sent21 me an example of a desirable Utopia: a draft of a history entitled The American Adventure. The adventurers come from ‘Eleutheropolis’. Strife has arisen between Christians and pagans. The Prince seeks to compose party differences but expels the strangers. The new adventurers are accepted and the Christianising of the populace is undertaken. Schism and dispute excluded, etc.

. . .

Mr Wood complains22 of his deafness and considers coming to London to consult a doctor; but he fears a cure might make him worse. He worries about how I can get my Lives to him securely.

. . .

Sir James Long23 tells me there is severe drought again in Wiltshire: there is no grass or hay to cut in the fields.

. . .

Yesterday evening Mr Wood sent his pretty niece – what amorous elegies I could write for her – to call on me, and I have let her take parts one and two of my book to him at last. I have a great many more things to insert, and ten more Lives I would like to add, but no time.

Mr Wylde has given24 me a recipe for curing Mr Wood’s deafness. Mr Wood believes his deafness is caused by a cold moist head and a cold moist stomach, which give rise to noises in his head. I hope Mr Wylde’s recipe will work!

. . .

Mr Wood has sent me25 5s. He is pleased with my Lives even though they contain many things that are not fit to be published.

I went to a tavern26 with John Lacy, a player, who was Mr Ogilby’s apprentice when he had his dancing school in Grays Inn Lane, and I took down notes to add to my Life of Mr Ogilby. Among other things, John Lacy told me that Mr Ogilby would never say where in Scotland he was born as he hoped (drollingly) that there would be as much contention over the place of his birth as there is over Homer’s.

. . .

Sir William Petty writes from Ireland (where he feels he is living in a place full of exasperated enemies) to say he is not forward with the printing of his Political Arithmetic because he intends to compare his current draft with the one in Mr Southwell’s hand, which he corrected in 1679.

On behalf27 of the Royal Society, Sir William has gone to some trouble over the elephant that was so unfortunately burnt. But the owner will not part with the skeleton, guts or trunk, which he hopes to show for profit (so they cannot be obtained for the Royal Society’s repository). Sir William says he is surprised that English and Dutch surgeons living in India have not already made a perfect anatomy of the creature.

. . .

I told the Royal Society28 today that recently I saw a live marten in a shop in Cornhill. I think many of them are bred in England, and my friend Mr Wylde has received a number of skins from a tenant of his.

. . .

I hope29, in a few weeks’ time, to see my beloved Oxford again. How much I wish the history of Jesuitism which George Ent unluckily gave to the Bodleian on my behalf were erased out.

I am concerned30 that in my Lives there are things that will cut my throat if they are not cut out. There are, for example, severe touches in my account of the life of Sir Richard Boyle, Earl of Cork (father of Robert Boyle) – perhaps I should not have included what my friend Anthony Ettrick told me about his amours and bastards. My Life of Dr Wallis is another difficulty.

If I die in London, as seems most likely, I wonder where I should be buried? Perhaps in my parish church, St Martin’s Outwych, near the door, like a poor penitent with a foot-square inscription. Or perhaps in the non-conformist churchyard by the artillery ground in Moorfields?

. . .

I fear the truths31 set out in my book will breed trouble – veritas odium parit (truth begets hatred). I have written too much truth, some of it of those who are still alive. In my book the truth is set down in its pure and natural state, not falsely coloured. This pleases me as an antiquary, but my Lives are not fit to be published. I have been writing them for my friend Mr Wood and have included many rude, undigested, unpolished and frivolous things.

. . .

I met with32 old Mr Beeston, ‘the Chronicle of the Stage’, today and we talked about the English poets he has known. He will give me notes on their lives. His father was master of the . . . playhouse. Knowing the uncertainty of life, and how few there are who transmit memories to posterity, I am ever more eager to pursue what I have begun.

. . .

I have written up the Lives of Mr Shakespeare and Mr Spenser:

Mr William Shakespeare

Mr William Shakespeare was born33 at Stratford-upon-Avon in the county of Warwick. His father was a butcher and I have been told heretofore by some of the neighbours that when he was a boy he exercised his father’s trade, but when he killed a calf he would doe it in a high style, and make a speech. There was at that time another butcher’s son in this town that was held not at all inferior to him for a natural wit, his acquaintance and coetanean, but died young.

This William, being inclined naturally to poetry and acting, came to London, I guess, about 18; and was an actor at one of the play-houses, and did act exceedingly well (now Ben Jonson was never a good actor, but an excellent instructor). He began early to make essays at dramatic poetry, which at that time was very low; and his plays took well.

He was a handsome, well shaped man: very good company, and of a very ready and pleasant smooth wit. The humour of . . . the constable, in Midsomernight’s Dreame, he happened to take at Grendon in Bucks – I think it was Midsomer night that he happened to lye there – which is the road from London to Stratford, and there was living that constable about 1642, when I first came to Oxford: Mr Josias Howe is of that parish, and knew him. Ben Jonson and he did gather humours of men daily where ever they came. One time as he was at the tavern at Stratford-super-Avon, one Combes, an old rich usurer, was to be buried, he makes there this extemporary epitaph:

Ten in the hundred the Devill allowes,

But Combes will have twelve, he sweares and vowes:

If any one askes who lies in this tombe,

‘Hoh!’ quoth the Devill, ‘’tis my John o Combe.’

He was wont to go to his native country once a year. I think I have been told that he left 2 or 300 li. per annum there and thereabout to a sister. Vide: his epitaph in Dugdale’s Warwickshire.

I have heard Sir William Davenant and Mr Thomas Shadwell (who is counted the best comedian we have now) say that he had a most prodigious wit, and did admire his natural parts beyond all other dramatical writers. He was wont to say (Ben Jonson’s Underwoods) that he ‘never blotted out a line in his life’; said Ben Jonson, ‘I wish he had blotted-out a thousand.’

His comedies will remain wit as long as the English tongue is understood, for that he handles mores hominum. Now our present writers reflect so much upon particular persons and coxcombeities, that twenty years hence they will not be understood.

Though, as Ben Jonson says of him, that he had but little Latin and less Greek, he understood Latin pretty well, for he had been in his younger years a schoolmaster, in the country – this from Mr . . . Beeston.

Mr Edmund Spenser34

Mr Edmund Spenser was of Pembroke-hall in Cambridge; he missed the fellowship there, which Bishop Andrewes got. He was an acquaintance and frequenter of Sir Erasmus Dreyden. His mistress, Rosalind, was a kinswoman of Sir Erasmus’s lady’s. The chamber there at Sir Erasmus’s is still called Mr Spenser’s chamber. Lately, at the College taking-down the wainscot of his chamber, they found an abundance of cards, with stanzas of the Faerie Queen written on them. – This from John Dryden, Esq., Poet Laureate.

Mr Beeston says he was a little man, wore short hair, a little band and little cuffs.

Mr Samuel Woodford (the poet, who paraphrased the Psalms) lives in Hampshire near Alton, and he told me that Mr Spenser lived sometime in these parts, in this delicate sweet air; where he enjoyed his muse, and writ good part of his verses.

I have said before that Sir Philip Sidney and Sir Walter Raleigh were his acquaintance. He had lived some time in Ireland, and wrote a description of it, which is printed with Morison’s History, or Description, of Ireland.

Sir John Denham told me that Archbishop Usher, Lord Primate of Armagh, was acquainted with him, by this token: when Sir William Davenant’s Gondibert came forth, Sir John asked the Lord Primate if he had seen it. Said the Primate, ‘Out upon him, with his vaunting preface, he speaks against my old friend, Edmund Spenser.’

In the south crosse-aisle of Westminster abbey, next the door, is this inscription:

Here lies (expecting the second coming of our Saviour Christ Jesus) the body of Edmund Spenser, the Prince of Poets of his time; whose divine spirit needs no other witness then the works which he left behind him. He was borne in London, in the year 1510, and died in the year 1596.

. . .

My mother has written to tell me that she has been ill for three weeks and now her eyes are a little sore.

. . .

At my mother’s request35, Mr Paschall has supplied his wife’s recipe for lapis calamine for sore eyes, and has explained how to apply the cure. The ointment is made from finely powdering the lapis calamine and mixing it with butter.

. . .

On this day36 my brother Tom died at Sarum. I will write to my friend the astrologer Charles Snell, for an account of my poor brother’s demise.

. . .

Charles Snell tells me he had not heard my brother was ill until he was dead. He had no learned physician with him, only drunken Jack Chapman, the sometime apothecary at Bath.

. . .

I have brought37 more of my Lives to Oxford for Mr Wood. I have been here a week, refreshing my soul among ingenious acquaintances. I feel I owe adoration to Oxford’s very buildings and groves, and am ready almost to offer sacrifice, when I find myself growing young again here. I am reminded of Ovid’s account of Medea rejuvenating old Aeson that gave my friend Francis Potter the idea of blood transfusion.

. . .

It is ringing all over St Albans that Sir Harbottle Grimston, Master of the Rolls, removed the coffin of renowned Lord Bacon to make room for his own in the vault of St Michael’s Church.

. . .

I am an ignorant fellow of but little learning. It has been suggested to me that I might succeed Dr Lamphire as Principal of Hart Hall. But surely they will choose some more learned man, like Dr Plot.

Mr Ashmole and I38 have been making a collection of the nativities of learned men from the manuscripts of old English astrologers who lived over a hundred years ago. These manuscripts used to belong to Mr William Lilly – who died at his house in Hersham on 9 June this year – but now they are in the possession of Mr Ashmole. We work on the manuscripts together: Mr Ashmole turning over the pages and reading them aloud while I transcribe. By April I hope we will have got through forty volumes. After Christmas I will visit him at his house in Lambeth every Sunday to this purpose. Each volume takes us about an hour. Also, after Christmas, when the opiating quality of the mince pies has been exhaled, I will continue with Mr Beeston recording the details he remembers of the lives of the poets.

Mr Ashmole also has39 Mr Lilly’s account of his own life. He was born on May Day and if he had lived until next May he would have been full fourscore. In the last almanac that Mr Lilly wrote by his own hand in 1677, before he went blind, he predicted the great comet that appeared last year. I must remember to bind up the almanac with some other pamplets, for it is very considerable and should not be lost.

But what encouragement does one have to do such things, for which one receives no thanks, but only scorn and contempt: O curva in terras anima (Oh, crooked souls that bow to earth).

. . .

Today I was smoking40 a pipe of tobacco at my friend Mr Wylde’s house when it suddenly came to me that Mr Wood might succeed Dr Lamphire at Hart Hall and secure himself an income. He is a man who makes no bustle in the world, but who is there to compare with him in merit?

. . .

I am too late41! Old Mr Beeston has died before I could get from him more details of the lives of the English poets! Alas! Alas! Those details have gone with him into oblivion and nothing can retrieve them now. He died at his house in Bishopgate Street. Mr Shipey in Somerset House has his papers.

. . .

I went to visit42 Mr Fabian Philips and took down his life from his mouth. His house is over against the middle of Lincoln’s Inn garden in Chancery Lane. He reproached me with never finishing any of my work. He was a barrister at Middle Temple, but grows blind and lonely and miserable now. I must see him again to cheer him. He told me that sixty-nine years ago, there were only two attorneys in the whole of Worcestershire. But now there is one in every market town, about a hundred, he believes.

Two days before43 Charles I was beheaded Mr Fabian Philips wrote a ‘Protestation Against the Intended Murder of the King’ and printed it and caused it to be put upon the posts. When all the courts in Westminster Hall were voted down, he wrote a book to justify them and the Speaker and Keepers of the Liberty sent him thanks. Mr Fabian Philips assures me that King Charles’s plain coffin cost just six shillings.

. . .

The Earl of Clarendon44 tells me that when his father was writing his history of our times – from the reign of Charles I to the Restoration of Charles II – the pen fell out of his hand. He picked it up to continue writing and it fell again. This is how he realised that he had palsy. It is said the history is very well done, but his son will not print it. Nor will he print his father’s Life, written by himself, because he says it is too soon (his father died in 1674).

. . .

I have consulted45 Sir James Long, of Draycot Cerne in Wiltshire, on the cutting of a canal to join the rivers Thames and Avon. He has referred me to Bills in Parliament for this and another such project, but expresses himself strongly against it (considering the plan unfeasible, spoiling of land, and proposed only by adventurers who do not intend to act on their proposals, etc.). He mentions alternative routes for the cutting, and the objection to each. Cutting through Cricklade is a possibility, and Sir James Long has consulted his cousin, who will help. He warns of stony ground and scarcity of water, but is glad to be of service, even so, and will await my response. Meanwhile, he interests himself in witch trials.

. . .

I have taken care of Sir James Long’s hawk, and he has reimbursed me.

. . .

The second reading46 of the Bill for marrying the rivers Thames and Avon by a three-mile cut near Malmesbury has revived in my mind the notion I have entertained for many years of making a boat to be rowed with sheels, or paddles, by a crank instead of oars. Such a boat would suit better the narrowness of the cut and be easier to propel against the strong stream. I think Mr Potter’s concave cylinders could be fitted to the bottom of the boats.

. . .

London has become47 so big and populous that the New River of Middleton can only serve the pipes to private houses twice a week.

. . .

Now that the warmer weather comes on I grow exceedingly active and begin to consider that we are all mortal men, and that we must not lose TIME.

If Mr Wood confirms he is alive and in Oxford, I will send him my collections – I would not have them go astray.

When Lord Norris48 of Rycote comes to Oxfordshire, I will certainly wait on him, for he has been kind in presenting me with a map of Rome by Pyrrho Ligurio, which should be engraved by Mr White, Mr Loggan’s scholar. I hope Mr Wood will subscribe to this good work.

. . .

I have had49 my Designatio de Easton Piers bound up between hard boards to preserve it.

. . .

I have now sent50 to Mr Wood the third volume of my Lives. I have also sent him Mr Hobbes’s recently published Tracts.

. . .

When I was staying51 with Sir Robert Henley in Hants., in solitude and secluded among the beech trees, I wrote a trifle that I am minded to show to Mr Wood. It is a description in verse and prose of the landscape that was within range of view.

. . .

Mr William Penn52, the Quaker, has set off towards Deale to sail for Pennsylvania, which was named after him last year (4 March 1681) when the King granted him and his heirs a province in America, in payment of the 10,000 li. that was owed to his father (20,000 li. considering the interest). His patent is from the beginning of the 40th degree to 43 degrees in latitude, and 5 degrees longitude from Chisapeake Bay. God send him a prosperous and safe voyage. He is my countryman, since his ancestors lived in Minty in the Hundred of Malmesbury.

. . .

My time is taken up with mundane affairs and I am out of humour.

. . .

Today I was sent a trunk of my books, papers, manuscripts and precious objects from Wiltshire that I have not seen for the last eleven years. I wish I could have all my books together in one place.

. . .

From Africa53, Mr Wylde Clerke has written to tell me that the plant I enquired about is unknown to the Moors. As to poisons, they know only mercury. He says he might be able to find out more about the plant if he could have more details of it. He promises to observe the methods of preserving plants and berries. As to magic, he finds that alleged manifestations are spurious and no prescription can be found in books. Alleged control of death is also shown to be false. He says they practise cruel tortures on rebels.

. . .

Sir Henry Blount54, who is over eighty years of age, his mind still strong, has been taken very ill in London: his feet extremely swollen. He has gone to Tittinghanger. His motto is: Loquendum est cum vulgo, sentiendum cum sapientibus (Speak with the vulgar, think with the wise). He is fond of saying that he does not care to have his servants go to church lest they socialise with other servants and become corrupted into visiting the alehouse and debauchery. Instead he encourages them to go and see the executions at Tyburn, which, he claims, have more influence over them than all the oratory in the sermons.

. . .

Thomas Merry55, who was Sir Jonas Moore’s disciple and an excellent logist, has died. He redid all of Euclid in a shorter and clearer manner than ever before, but he left his work unstitched so that when I called to enquire for it after his death, the pages had departed like Sybillina folia, and several were lost. I collected up what I could and took the loose sheets to the Royal Society. There they were committed to the care of Mr Paget, but he deemed them imperfect and unfit to be printed. What will become of them now, God knows!

. . .

My mother tells me she is seventy-three years of age.

. . .

Today at the Royal Society56 we discussed medicated springs. Sir John Hoskyns and I confirmed that in Surrey and Kent, as far as Shooter’s Hill, the earth is full of the pale yellow mineral known as pyrites.

. . .

The curious clock57 that Mr Nicholas Mercator made and presented to His Majesty is for sale from Mr Fromantle’s for 200 li. It is a foot in diameter and it shows the difference between the sun’s motion and apparent motion. The clock was neglected at court, even though the King commended it. It was sold to a watchmaker for 5 li., then on to Mr Fromantle.

. . .

My loyal, dear, useful58, faithful friend George Johnson has died. He was a strong and lusty man, but caught a malignant fever from the Earl of Abingdon’s brother, which carried him off. He left London last Monday, got home on Tuesday, was ill that night, better the next day, but then fell ill again with intermitting fever and died. He was born at Bowdon Park within four miles of where I was born. We studied at Blandford School and the Middle Temple together. If he had become Master of the Rolls, as he was expected to do, he would have made me one of his secretaries with 500 li. a year. I shall never see such an opportunity again. If I had 500 li. a year I would use it to the greater glory of God and to help my ingenious friends, Mr Wood above all.

. . .

I fear that I should not have put my Book of Lives, concerning so many great persons still living, into even Mr Wood’s hands. I ought to castigate and castrate some of the things in it that are too true and biting, and cast them aside somewhere at the end of the book to be referred to in an occult and secret way (e.g. 125 to be 521 or done retrograde).

I think it will be a long time before I get to Oxford again.

The chalybeate spring59 I discovered at Seend, near Devizes, in 1666, will now, I hope, become a fashionable resort. When I presented samples of the water to the Royal Society, they were much admired. I did not have enough authority personally to bring the waters into vogue, but I will insert notice of them into next year’s almanac and the gazette.

. . .

On this day60 Mr Ashmole’s museum in Oxford was opened to the public. It is a large stately new building next to the Bodleian Library, which will house the collection of rarities, curiosities and antiquities that he has given to the University. The collection was sent from South Lambeth to Oxford by barge: enough to fill twelve carts. Dr Robert Plot has been appointed the first Keeper of the Museum.

. . .

William Penn, the Quaker, writes to me from Pennsylvania, and sends his greetings to Sir William Petty, Mr Hooke, Mr Wood and Mr Lodwick. He says he prides himself on the good opinion of the gentlemen of the Royal Society and professes himself a votary of the prosperity of our enquiries since ‘It is one step to Heaven to return to nature.’ He praises our experimental age where everything is tried by the measure of experience, as against the ill tradition of foolish credulity, and he solicits the continuation of our friendship to his undertaking.

In his letter, Mr Penn describes the fertility of the country in trees, forests and crops. The soil is good and there are many springs. There are delightful fruits, as good as any in Europe, plentiful fish in the rivers and an abundance of vines, which he intends to cultivate with the help of Frenchmen from Languedoc and Poitou. The river is full of sturgeon that can be seen leaping from it by day and heard at night. The fish can be roasted or pickled. Several people from other colonies – Virginia, Maryland, New England, Road Island, New York – are moving to Pennsylvania.

Mr Penn is making61 it his business to establish a virtuous economy and so he sits in council twice a week and has held two assemblies, which, he says, received him with all kindness.

. . .

My friend Jane Smyth62 is in extreme danger of dying due to suppression of urine. Her ureter is stopped.

. . .

Earlier this month63 I was robbed. My friend Thomas Pigott hopes the mishap has not spoilt my Knightsbridge rounds by moonlight and that he may be merry with me again in the middle of the night at the World’s End.

. . .

I have called on64 Mr Bushnell, an ingenious stonecutter, who lives opposite St James’s Park on the road that runs to Knightsbridge. He gave me an account of the curious marble that was used to build Charing Cross, which was pulled down around 1647. Afterwards, there was a fashion for using the marble for salt cellars and knife-handles. It was a sort of hair-coloured grey and full of little (as it were) kernels. Recently the quarry from which the marble came was rediscovered in Sussex; it was overgrown with trees and bushes, but came to light when the roots of an old oak tree were grubbed up.

. . .

Sir Jonas Moore’s books65 are for sale – it is such a pity that so good a collection is at risk of being scattered. I will catalogue them, and price them as far as possible, for Dr Wallis, in the hope that he can find a buyer.

Sir Jonas Moore intended66 to leave his books to the Royal Society, but when he died in August 1679, he had not made a will, to the Royal Society’s great loss. At the Restoration, he was made Master Surveyor of His Majesty’s ordinance and armouries. I often heard him say how Mr Wylde, who studied mathematics with him, interested him in surveying in the first place. When he surveyed the fens, he observed that the line that the sea made on the beach is not straight. He made banks to follow the line and got much credit as a result for keeping the sea out of Norfolk.

. . .

Alas67, Oxford’s Vice Chancellor has not agreed to purchase Sir Jonas Moore’s books for the Bodleian Library. Dr Wallis tells me they will take the chance of picking up at the auction sale such important mathematical works as they lack. Perhaps one of the Cambridge colleges will purchase the collection so it can stay together.

. . .

Sir Isaac Newton68 tells me the cost of building prevents Trinity College, Cambridge, from buying books at present. He has been to the Vice Chancellor, who asks the price and desires to see the catalogue of Sir Jonas Moore’s books, but it is not clear whether the University will be able to purchase them either, being at present very low. Mr Newton intends to bring the matter before the Heads of Colleges at the next opportunity.